The Search for Meaning and the Conundrum of Authority in the Castle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Literary Tradition in Roth's Kepesh Trilogy

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 16 (2014) Issue 2 Article 8 European Literary Tradition in Roth's Kepesh Trilogy Gustavo Sánchez-Canales Autónoma University Madrid Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the American Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Education Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Reading and Language Commons, Rhetoric and Composition Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Television Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Sánchez-Canales, Gustavo. -

Complete Stories by Franz Kafka

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka Back Cover: "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. The foreword by John Updike was originally published in The New Yorker. -

The Kafka Protagonist As Knight Errant and Scapegoat

tJBIa7I vAl, O7/ THE KAFKA PROTAGONIST AS KNIGHT ERRANT AND SCAPEGOAT THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Mary R. Scrogin, B. A. Denton, Texas August, 1975 10 Scrogin, Mary R., The Kafka Protagonist as night Errant and Scapegoat. Master of Arts (English), August, 1975, 136 pp., bibliography, 34 titles. This study presents an alternative approach to the novels of Franz Kafka through demonstrating that the Kafkan protagonist may be conceptualized in terms of mythic arche- types: the knight errant and the pharmakos. These complementary yet contending personalities animate the Kafkan victim-hero and account for his paradoxical nature. The widely varying fates of Karl Rossmann, Joseph K., and K. are foreshadowed and partially explained by their simultaneous kinship and uniqueness. The Kafka protagonist, like the hero of quest- romance, is engaged in a quest which symbolizes man's yearning to transcend sterile human existence. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION . .......... 1 II. THE SPARED SACRIFICE...-.-.................... 16 III. THE FAILED QUEST... .......... 49 IV. THE REDEMPTIVE QUEST........... .......... 91 BIBLIOGRAPHY.. --...........-.......-.-.-.-.-....... 134 iii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Speaking of the allegorical nature of much contemporary American fiction, Raymond Olderman states in Beyond the Waste Land that it "primarily reinforces the sense that contemporary fact is fabulous and may easily refer to meanings but never to any one simple Meaning." 1 A paraphrase of Olderman's comment may be appropriately applied to the writing of Franz Kafka: a Kafkan fable may easily refer to meanings but never to any one Meaning. -

The Castle and the Village: the Many Faces of Limited Access

01-7501-1 CH 1 10/28/08 5:17 PM Page 3 1 The Castle and the Village: The Many Faces of Limited Access jorrit de jong and gowher rizvi Access Denied No author in world literature has done more to give shape to the nightmarish challenges posed to access by modern bureaucracies than Franz Kafka. In his novel The Castle, “K.,” a land surveyor, arrives in a village ruled by a castle on a hill (see Kafka 1998). He is under the impression that he is to report for duty to a castle authority. As a result of a bureaucratic mix-up in communications between the cas- tle officials and the villagers, K. is stuck in the village at the foot of the hill and fails to gain access to the authorities. The villagers, who hold the castle officials in high regard, elaborately justify the rules and procedures to K. The more K. learns about the castle, its officials, and the way they relate to the village and its inhabitants, the less he understands his own position. The Byzantine codes and formalities gov- erning the exchanges between castle and village seem to have only one purpose: to exclude K. from the castle. Not only is there no way for him to reach the castle, but there is also no way for him to leave the village. The villagers tolerate him, but his tireless struggle to clarify his place there only emphasizes his quasi-legal status. Given K.’s belief that he had been summoned for an assignment by the authorities, he remains convinced that he has not only a right but also a duty to go to the cas- tle! How can a bureaucracy operate in direct opposition to its own stated pur- poses? How can a rule-driven institution be so unaccountable? And how can the “obedient subordinates” in the village wield so much power to act in their own self- 3 01-7501-1 CH 1 10/28/08 5:17 PM Page 4 4 jorrit de jong and gowher rizvi interest? But because everyone seems to find the castle bureaucracy flawless, it is K. -

Featuring Martin Kippenberger's the Happy

FONDAZIONE PRADA PRESENTS THE EXHIBITION “K” FEATURING MARTIN KIPPENBERGER’S THE HAPPY END OF FRANZ KAFKA’S ‘AMERIKA’ ACCOMPANIED BY ORSON WELLES’ FILM THE TRIAL AND TANGERINE DREAM’S ALBUM THE CASTLE, IN MILAN FROM 21 FEBRUARY TO 27 JULY 2020 Milan, 31 January 2020 – Fondazione Prada presents the exhibition “K” in its Milan venue from 21 February to 27 July 2020 (press preview on Wednesday 19 February). This project, featuring Martin Kippenberger’s legendary artworkThe Happy End of Franz Kafka’s “Amerika” accompanied by Orson Welles’ iconic film The Trial and Tangerine Dream’s late electronic album The Castle, is conceived by Udo Kittelmann as a coexisting trilogy. “K” is inspired by three uncompleted and seminal novels by Franz Kafka (1883-1924) ¾Amerika (America), Der Prozess (The Trial), and Das Schloss (The Castle)¾ posthumously published from 1925 to 1927. The unfinished nature of these books allows multiple and open readings and their adaptation into an exhibition project by visual artist Martin Kippenberger, film director Orson Welles, and electronic music band Tangerine Dream, who explored the novels’ subjects and atmospheres through allusions and interpretations. Visitors will be invited to experience three possible creative encounters with Kafka’s oeuvre through a simultaneous presentation of art, cinema and music works, respectively in the Podium, Cinema and Cisterna.“K” proves Fondazione Prada’s intention to cross the boundaries of contemporary art and embrace a vaste cultural sphere, that also comprises historical perspectives and interests in other languages, such as cinema, music, literature and their possible interconnections and exchanges. As underlined by Udo Kittelmann, “America, The Trial, and The Castle form a ‘trilogy of loneliness,’ according to Kafka’s executor Max Brod. -

The Hero As an Outsider in Franz Kafka's Novels

THE HERO AS AN OUTSIDER IN FRANZ KAFKA'S NOVELS: DER PROZESS AND DAS SChLOSS A THESIS SUBHITTED TO THE DEPARTl1ENT OF FOREIGN LANGUAGES AND THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE KANSAS STATE TEAC HERS COLLEGE OF EMPORIA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUI RE}1ENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF . 1'-1ASTER OF ARTS By RENATE KER~.,rICK August 1972 ~~?_'(~fV ~uem~~~dea ~or~W e~~ JOJ P~~ddV .1 r AC KNO\rJLEDGMENT The writer wishes to express sincere appreciation to Dr. David E. Travis, Chairman of the Department of Foreign Languages, Kansas State Teachers College, Emporia, without whose active interest and constructive criticism this study would not have been possible. R. K. PREFACE Many Kafka scholars have approached the study of his works with the preconception that the artist's own experiences, emotions, and sentiments must be reflected in the creations, thereby denying from the start that the author l.vas able to rai se his liJork above the personal level. Other critics were determined to discover in Kafka's works certain characteristics and weaknesses which they believed to have discerned in the artist him sell. One must allow these critics their own views. Perhaps they are correct in the assumption that it is impossible to separate Kafka's life from his works com pletely. For it is certainly true that, particularly in two of his novels, Der Prozess and Das Schloss, he continues to use variations on the same theme •. In both novels, the apparent concern is with man's attempt to integrate himself into the company of his fellowman. -

EXISTENTIAL CRISIS in FRANZ Kl~Fkl:T

EXISTENTIAL CRISIS IN FRANZ Kl~FKl:t. Thesis submitted to the University ofNor~b ~'!e:n~al for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Ph.Ho§'Ophy. By Miss Rosy Chamling Department of English University of North Bengal Dist. Darjeeling-7340 13 West Bengal 2010 gt)l.IN'tO rroit<. I • NlVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL P.O. NORTH BENGAL UNIVERSITY, HEAD Raja Rammohunpur, Dist. Da~eeling, DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH West Bengal, India, PIN- 734013. Phone: (0353) 2776 350 Ref No .................................................... Dated .....?.J..~ ..9 . .7.: ... ............. 20. /.~. TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN This is to certify that Miss Rosy Cham!ing has completed her Research Work on •• Existential Crisis in Franz Kafka". As the thesis bears the marks of originality and analytic thinking, I recommend its submission for evaluation . \i~?~] j' {'f- f ~ . I) t' ( r . ~ . s amanta .) u, o:;.?o"" Supervis~r & Head Dept. of English, NBU .. Contents Page No. Preface ......................................................................................... 1-vn Acknowledgements ...................................................................... viii L1st. ot~A'b o -rev1at1ons . ................................................................... 1x. Chapter- I Introduction................................................... 1 1 Chapter- II The Critical Scene ......................................... 32-52 Chapter- HI Authority and the Individual. ........................ 53-110 Chapter- IV Tragic Humanism in Kafka........................... 111-17 5 Chapter- V Realism -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

NUREMBERG) Judgment of 1 October 1946

INTERNATIONAL MILITARY TRIBUNAL (NUREMBERG) Judgment of 1 October 1946 Page numbers in braces refer to IMT, judgment of 1 October 1946, in The Trial of German Major War Criminals. Proceedings of the International Military Tribunal sitting at Nuremberg, Germany , Part 22 (22nd August ,1946 to 1st October, 1946) 1 {iii} THE INTERNATIONAL MILITARY TRIBUNAL IN SESSOIN AT NUREMBERG, GERMANY Before: THE RT. HON. SIR GEOFFREY LAWRENCE (member for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) President THE HON. SIR WILLIAM NORMAN BIRKETT (alternate member for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) MR. FRANCIS BIDDLE (member for the United States of America) JUDGE JOHN J. PARKER (alternate member for the United States of America) M. LE PROFESSEUR DONNEDIEU DE VABRES (member for the French Republic) M. LE CONSEILER FLACO (alternate member for the French Republic) MAJOR-GENERAL I. T. NIKITCHENKO (member for the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) LT.-COLONEL A. F. VOLCHKOV (alternate member for the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) {iv} THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, THE FRENCH REPUBLIC, THE UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND, AND THE UNION OF SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLICS Against: Hermann Wilhelm Göring, Rudolf Hess, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Robert Ley, Wilhelm Keitel, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Alfred Rosenberg, Hans Frank, Wilhelm Frick, Julius Streicher, Walter Funk, Hjalmar Schacht, Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, Karl Dönitz, Erich Raeder, Baldur von Schirach, Fritz Sauckel, Alfred Jodl, Martin -

51.Dr.Ajoy-Batta-Article.Pdf

www.TLHjournal.com Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 UGC-Approved Journal An International Refereed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 2.24 (IIJIF) Franz Kafka and Existentialism Dr. Ajoy Batta Associate Professor and Head Department of English, School of Arts and Languages Lovely Professional University, Phagwara (Punjab) Abstract: Franz Kafka was born on July 3, 1883 at Prague. His posthumous works brought him fame not only in Germany, but in Europe as well. By 1946 Kafka‟s works had a great effect abroad, and especially in translation. Apart from Max Brod who was the first commentator and publisher of the first Franz Kafka biography, we have Edwin and Willa Muir, principle English translators of Kafka‟s works. Majority studies of Franz Kafka‟s fictions generally present his works as an engagement with absurdity, a criticism of society, element of metaphysical, or the resultant of his legal profession, in the course failing to record the European influences that form an important factor of his fictions. In order to achieve a newer perspective in Kafka‟s art, and to understand his fictions in a better way, the present paper endeavors to trace the European influences particularly the influences existentialists like Kierkegaard, Dostoevsky and Nietzsche in the fictions of Kafka. Keywords: Existentialism, absurd, meaningless, superman, despair, identity. Research Paper: Friedrich Nietzsche is perhaps the most conspicuous figure among the catalysts of existentialism. He is often regarded as one of the first, and most influential modern existential philosopher. His thoughts extended a deep influence during the 20th century, especially in Europe. With him existentialism became a direct revolt against the state, orthodox religion and philosophical systems. -

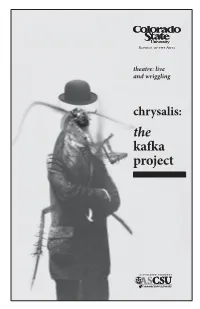

The Kafka Project

theatre: live and wriggling chrysalis: the kafka project CSU Theatre presents chrysalis: the kafka project World Premiere Created by Walt Jones and the Company Original Music by Peter Sommer and James David Directed by Walt Jones Scenic Design by Maggie Seymour The Kennedy Center American College Theater Festival™ 44, part of the Rubenstein Arts Access Program, Lighting Design by Alex Ostwald is generously funded by David and Alice Rubenstein. Costume Design by Janelle Sutton Sound Design by Parker Stegmaier Additional support is provided by the U.S. Department of Education, Projections Design by Nicole Newcomb the Dr. Gerald and Paula McNichols Foundation, Properties Design by Brittany Lealman The Honorable Stuart Bernstein and Wilma E. Bernstein, and Production Stage Manager, Amy Mills the National Committee for the Performing Arts. Assistant Stage Manager, Tory Sheppard This production is entered in the Kennedy Center American College Theater THE PROGRAMME Festival (KCACTF). The aims of this national theater education program are to identify and promote quality in college-level theater production. To From Amerika . Michael Toland this end, each production entered is eligible for a response by a regional “Report to An Academy” . Tim Werth KCACTF representative, and selected students and faculty are invited to Metamorphosis . Michael Toland, Kat Springer, Michelle Jones, participate in KCACTF programs involving scholarships, internships, grants Nick Holland, Willa Bograd, Sean Cummings and awards for actors, directors, dramaturgs, playwrights, designers, stage “The Country Doctor” . Sean. Cummings, Emma Schenkenberger, managers and critics at both the regional and national levels. Jeff Garland, Willa Bograd, Kat Springer, Kaitlin Jaffke, Tim Werth, Michelle Jones, Nick Holland, Trevor Grattan Productions entered on the Participating level are eligible for inclusion at the Metamorphosis . -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Cold War Love: Producing

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Cold War Love: Producing American Liberalism in Interracial Marriages between American Soldiers and Japanese Women A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies by Tomoko Tsuchiya Committee in charge: Professor Yen Le Espiritu, Chair Professor Ross Frank Professor Takashi Fujitani Professor Denise Ferreira da Silva Professor Lisa Yoneyama 2011 Copyright Tomoko Tsuchiya, 2011 All Rights Reserved The dissertation of Tomoko Tsuchiya is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2011 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………iii Table of Contents………………………………………………………...iv List of Figures……………………………………………………………..v Acknowledgements……………………………………………..……..…vi Vita………………………………………………….………………….....ix Abstract of the Dissertation ……...……………………………………….x Introduction………………………………................................................ 1 Part I Love and Violence: Production of the Postwar U.S.-Japan Alliance…….36 Chapter One Dangerous Intimacy: Sexualized Japanese Women during the U.S. Occupation of Japan……...37 Chapter Two Intimacy of Love: Loveable American Soldiers in Cold War Politics.…...68