Preverbal Particles in Pingelapese: a Language of Micronesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buden-Etal2005.Pdf

98 PACIFIC SCIENCE . January 2005 Figure 1. Location of the Caroline Islands. along the shore. The average annual rainfall spp.) are the dominant trees on all but the ranges from about 363 cm in Chuuk (Merlin smallest atoll islands, where coastal scrub and and Juvik 1996) to 1,015 cm estimated in the strand predominate. All of the islands fall mountains on Pohnpei (Merlin et al. 1992). within the equatorial rain belt and are wet The land area on the numerous, wide- enough to support a mesophytic vegetation spread, low (1–4 m high) coralline atolls is (Mueller-Dombois and Fosberg 1998). All of miniscule. Satawan Atoll in the Mortlock the atolls visited during this survey are in- Islands, southern Chuuk State, has the largest habited or (in the case of Ant Atoll) have been total land area, with 4.6 km2 distributed so in the recent past. Ornamental shrubs, among approximately 49 islets (Bryan 1971). trees, and herbs are common in the settle- Houk (¼ Pulusuk Atoll), a lone islet west of ments, which are usually located on one or Chuuk Lagoon, is the largest single island several of the larger islets; the others are vis- (2.8 km2) among all of these outlyers. Coco- ited frequently to harvest coconuts, crabs, and nut (Cocos nucifera) and breadfruit (Artocarpus other forest products used by the community. Butterflies of the Eastern Caroline Islands . Buden et al. 99 materials and methods record from Kosrae, but this sight record re- quires confirmation.] Butterflies were collected by D.W.B. when the opportunity arose during biological sur- veys of several different taxonomic groups, Family Lycaenidae including birds, reptiles, odonates, and milli- Catochrysops panormus (C. -

Pohnpei : Household Income, Expenditure and the Role of Electricity

POHNPEI: HOUSEHOLD INCOME, EXPENDITURE, AND THE ROLE OF ELECTRICITY by James P. Rizer August 1985 Pacific Islands Development Program Resource Systems Institute East-West Center 1777 East-West Road Honolulu, Hawaii 96848, USA JAMES P. RIZER is a Research Fellow with the Pacific Islands Development Program (PIDP) at the East-West Center. He has conducted planning studies for a number of development projects in the Pacific region. Before joining PIDP, Rizer worked for the government of Fiji and the University of the South Pacific. The Pacific Islands Development Program is publishing this report for use by Pacific island governments. To ensure maximum dissemination of the material contained in the report, it is not copyrighted and island governments are encouraged to copy the report or portions of it at will. PIDP requests, however, that organizations, Institutions, and individuals acknowledge the source of any material used from the report. I CONTENTS Page No. List of Figures v List of Tables vi Foreword ix Preface xi Acknowledgments xiii List of Abbreviations xiv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 Chapter 1. DEVELOPMENT OF THE STUDY 5 Identifying a Site 5 Focus of the Study 5 The Questionnaires 10 Planning the Study 11 Chapter 2. POHNPEI: AN OVERVIEW 13 Location 13 Physical Characteristics 13 Flora and Fauna 14 History 14 Transportation and Communication 16 Social Services and Issues 17 Chapter 3. RURAL ELECTRIFICATION: A CONTEXT 19 Selected Data on Current Electricity Use 20 Energy Development Goals 25 Chapter 4. SOCIOECONOMIC PROFILE OF STUDY HOUSEHOLDS 29 Population 30 Economic Activity, Education, and the Use of Time 33 Income and Expenditure 38 Comparison of Sokehs and Uh 47 Distribution of Income 54 Other Household Characteristics 57 Chapter 5. -

The Eastern Mail (Waterville, Maine) Waterville Materials

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby The Eastern Mail (Waterville, Maine) Waterville Materials 4-23-1863 The Eastern Mail (Vol. 16, No. 42): April 23, 1863 Ephraim Maxham Daniel Ripley Wing Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/eastern_mail Part of the Agriculture Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Maxham, Ephraim and Wing, Daniel Ripley, "The Eastern Mail (Vol. 16, No. 42): April 23, 1863" (1863). The Eastern Mail (Waterville, Maine). 821. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/eastern_mail/821 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Waterville Materials at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Eastern Mail (Waterville, Maine) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. ■T ■■ MISOqLLAJSTY. ara subject, tbs parent may decide whioli iball go lo the war; the only brother of children THS SNAKE IN THE GRASS. nnder twelve, who ate dependent on his labor for support ; (he father of motherless cliildren BT JOSK a. 9AXI. under twelve, who are dependent nn his labor Coma, listen Rvhtta to me, ipy led.- lor supporf; whaTs tberif are d fatiiei'-and two OaOe, lleien to (ke Tor e spell I Let that terrible drum sons in the same family and household, and For n moment be dumb, two af IbMft'kfe iit'fhu mniidry sbi4ifce bf tifd' For jrbur nli'cte Is^oins to tell United States, ae non commieeianed officers, What befell A youth who loved liquor too weir. musicians, or privali^a, Iho reaidyie pr.gu«li faiii- A elevef young mnn was he, my lad, . -

^Isitls^S^^Ft Of

Tl"* in T>T*tnWnf \K>7 wr.-th.« of Mr I?iirh»r,an a a.rrninati..o. FARMERS ASD t ARMISU. iii'txii.g. The great rock.« aeeui to tij, Patietst i ALI. KLÜATTA HF TM, UKW-TOM*. I'an Weftke. N«Ttb (^.n,'""»- j'i '.»V»«lirgt«*.wl* opponents ' <" es Z ic.i.i.kv mm MMllMailil of ao-nc- ihr«. P..*,, with Mr" And yet, hr menr* fit m private indentation," mys¬ waiters a.-e no bapr*.' We hate a-t lost so much YACHT CLVtW » rr- Buchn(, .,, u. w i 1R t,., a .(* wc ree«ivrd. » .bot, I* It* firatda, ,,, Ifc, . (; ,.F. divulged. BOJd pauabaho (.um'«!, WAJ.!K> MM UM pcarer TV Tres-rer report teriously ADPKFS* OK RAUM» KMP.KN»»>f. The wu[\» aar mm, it . machine winch irf asaTe ^.tura» at it* Im», m miw) That 1Mb an of tie AMwwitüou, Tboojof. H. BeoAea i aarth y r*rstta »"». mm Trrk y^-i,, r ,,H waa «f W0..W0. Tb.» exp* j r bnvritw Im£ place underpay TV fmW tt b<< vcar .. s 'iTni The A.M«.W'n will ,,,, ^ that it waa anrounr-ed 6*55« r«irf n mad" to towe fl« the b loiMi .., pf th« I The At.nua! Agr:i-n!tura! Fan io Middlesex Coonty. yie'd* ir* rurf to v»-ry application of tofr'Bott. > fl7.<MV l-proverb . «i mai .>t |n the «<r-m i»f Theyisehfs //,,r',',, ,nd Th« Nrvr-Y>*it Tarac*,. rrto*t fraud", that have f>r»r been rx-riie- in k ..u »t ( i.nr. -

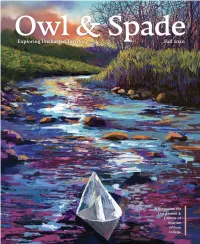

Owlspade 2020 Web 3.Pdf

Owl & Spade Magazine est. 1924 MAGAZINE STAFF TRUSTEES 2020-2021 COLLEGE LEADERSHIP EXECUTIVE EDITOR Lachicotte Zemp PRESIDENT Zanne Garland Chair Lynn M. Morton, Ph.D. MANAGING EDITOR Jean Veilleux CABINET Vice Chair Erika Orman Callahan Belinda Burke William A. Laramee LEAD Editors Vice President for Administration Secretary & Chief Financial Officer Mary Bates Melissa Ray Davis ’02 Michael Condrey Treasurer Zanne Garland EDITORS Vice President for Advancement Amy Ager ’00 Philip Bassani H. Ross Arnold, III Cathy Kramer Morgan Davis ’02 Carmen Castaldi ’80 Vice President for Applied Learning Mary Hay William Christy ’79 Rowena Pomeroy Jessica Culpepper ’04 Brian Liechti ’15 Heather Wingert Nate Gazaway ’00 Interim Vice President for Creative Director Steven Gigliotti Enrollment & Marketing, Carla Greenfield Mary Ellen Davis Director of Sustainability David Greenfield Photographers Suellen Hudson Paul C. Perrine Raphaela Aleman Stephen Keener, M.D. Vice President for Student Life Iman Amini ’23 Tonya Keener Jay Roberts, Ph.D. Mary Bates Anne Graham Masters, M.D. ’73 Elsa Cline ’20 Debbie Reamer Vice President for Academic Affairs Melissa Ray Davis ’02 Anthony S. Rust Morgan Davis ’02 George A. Scott, Ed.D. ’75 ALUMNI BOARD 2019-2020 Sean Dunn David Shi, Ph.D. Pete Erb Erica Rawls ’03 Ex-Officio FJ Gaylor President Sarah Murray Joel B. Adams, Jr. Lara Nguyen Alice Buhl Adam “Pinky” Stegall ’07 Chris Polydoroff Howell L. Ferguson Vice President Jayden Roberts ’23 Rev. Kevin Frederick Reggie Tidwell Ronald Hunt Elizabeth Koenig ’08 Angela Wilhelm Lynn M. Morton, Ph.D. Secretary Bridget Palmer ’21 Cover Art Adam “Pinky” Stegall ’07 Dennis Thompson ’77 Lara Nguyen A. -

Sapwtik Marine Protected Area. Lenger Community Five Year

Sapwtik Marine Protected Area Lenger Community Five Year Management Plan (2015 – 2020) Draft Version Date Prepared: September 08, 2015 Nett Municipality, Pohnpei State, Federated States of Micronesia Contributors to this document: Community of Lenger Partners: Conservation Society of Pohnpei (CSP): Kesdy Ladore, Jorge Anson, Kirino Olpet, Eliza Sailas, Hector Victor PIMPAC and OneReef Micronesia: Wayne Andrew Lenger Community Vision: We envision our community having abundant of natural resources and living happily in a healthy environment. Our Mission: We will achieve our vision through an organized and active community organization that is working with local and international partners to better manage our resources and improve community living standard. Acknowledgements: The Community of Lenger together with their village Chief Lephen Lenger (Mr. Salter Lohn) would like to thank the Conservation Society of Pohnpei (CSP), Pacific Islands Managed and Protected Area Community (PIMPAC) and OneReef Micronesia for facilitating and writing up or management plan. This plan has been in our mind and our hearts since the establishment of our MPA. With CSP, PIMPAC and OneReef, we were able to undertake a community participatory process to develop this plan. This plan embodies our dream of improving our communities in a healthy environment with abundant of resources. 1. All photos within this document are by Wayne Andrew © and used with his permission. The printing of this document was funded by OneReef Micronesia and the Conservation Society of Pohnpei. For additional copies or information regarding this management plan, please contact Conservation Society of Pohnpei Office at PO Box 2461, Kolonia Pohnpei, FSM 96941; Telephone (691) 320-5409; E-mail: [email protected] or contact village Chief Lephen Lenger, Mr. -

Biggest Battle of War Now on Before Teruel

V t H n t l E E I t dtattdrffltff gttMtfaa fw a tt THURSDAY, DECEMBER t 'AVEEAOE DAILY OIBUUIJITION ■ ta Chapter, o f Beta SIgml Phi for tSo Moeta ol Movemhar, 1881 WEArHEB I wOI awat tonight at 8 o'clodi at the Leen died aa a hasafd U, loaded •< U. « . Mroathm a ABOUT TOWN I Ilotel Sheridan. INSPECT PARKING with parked oara, a lira should I U aitfoie ^ “ twak out. and flra lighting appara- f tus should be unable to reach the 6.029 at tSe AadM iiaiirlyFH fFr S u ftttttg Robert Trim of Detroit scene. m/tm Snow or nibi taniglit aad Friday night l^y the leeal Im- HIcb., la vlalting frlenda In town AREAS A T SQUARE The committee. In Ita Inveatlga-, tone Qt CXrfeletliei day. saghOy •d Order of Red ICen will be tbla waek. He lived here two 3«ara Here Is Our After Christnu In Tinker hall tonight Inataad, ^ n y e ^ rd a y , found that by level MANCHESTER — A OTY OF VHXAGE (If ARM ago, bla father being government ling about IS feet into the west aide ~ at 8:8C ahaip. aeronautical Inapector In Baat Hart of tht parklet behind the ra ilrr^ ford. Hr. Trlgga waa later trana- UL. LVIL, NO. 77 AdvertM ag on Pnga 13) Selectmen’s Committee h - stotlon, It may be possible to park MANCHESTER. CONN., FRIDAY, DECEMBER SI, 1937 (FOURTEEN PAGES) amaU namber o f leeervationa ferred to FUat Thrilling p Hh x t h r e e c e n t s •Va < en to Bon-Bteariiera for the cara diagonally, as on Main street, Markdowiik 9 M both sides of the Square, this ▲ m y and N aey rlub'a New Tear'a AH o f the remaining prlaea ea- restigates Problem— To On Coats, Dresses and Millinery ■va party. -

Perry & Buden 1999

Micronesica 31(2):263-273. 1999 Ecology, behavior and color variation of the green tree skink, Lamprolepis smaragdina (Lacertilia: Scincidae), in Micronesia GAD PERRY Brown Tree Snake Project, P.O. Box 8255, MOU-3, Dededo, Guam 96912, USA and Department of Zoology, Ohio State University, 1735 Neil Ave., Columbus, OH 43210, USA. [email protected]. DONALD W. BUDEN College of Micronesia, Division of Mathematics and Science, P.O. Box 159, Palikir, Pohnpei, Federated States of Micronesia 96941 Abstract—We studied populations of the green tree skink, Lamprolepis smaragdina, at three main sites in Micronesia: Pohnpei (Federated States of Micronesia, FSM) and Saipan and Tinian (Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, CNMI). We also surveyed Rota (CNMI), where the skink has not been recorded in previous surveys, to verify its absence. Our main goal was to describe some basic biology traits at these sites. Observations were carried out between 1993 and 1998. We used focal animal observations and visual surveys to describe the relative abundance, elevational distribution, behavior (perch choice, foraging behavior, activity time), and coloration of the species at each of the three sites. This information was then used to compare these populations in order to assess the origin of the CNMI populations. As expected, we found no green tree skink on Rota. We found few differences among the three populations we did locate, Pohnpei, Tinian, and Saipan. Perch diameters and body orientations were similar between the three sites, as were population densities and foraging behaviors. However, Tinian’s lizards perched lower than those of Pohnpei or Saipan, probably due to the smaller trees available to them. -

Campbell's Great Mid-Summer

DANCING TONIGHT _ to Information from H«v. H. E. R. StechhoU, pastor Manche$ter- o f ViUage Charm a, Cheney iBrothera have King David Lodga of Odd Fel DANTE'SRESTAURANT ___ a government con- ,00 Lutheran church, will Uavo 10 Baat O ntor Strant OM Fellows BulMIng The' regular* monthly meeting lows at Its mecUng last night In tor manufacture of J56.350 thi^x^temoon for Webster, Maas., (Ctaaeided Adverttauig eu Page It) MANCHESTER, CONN., MONDAY, JUF.Y li>, 1940 (EOURIEEN PAGES) PRICE THREE CKNI'gbl of the Zipscr club will be held at Odd Fellows hall seated the offi wherd\^ will deliver the anniver- Fentaring Fierti Ctaina and Oystora On the V©L. LIX. Of BecVertfhiefi for the’d three o'clock tomorrow afternoon Ctem er Oyiiter Fries , Cmb Meat Cocktail on Brn^ard cers who will serve the lodge for aary aebmon at the golden jubilee ''' at the club's borne "o of Zion Lhttheran church o€ Wab- Ornlnutra EveryItiHra. and Sat. Nlghta. Songs At Tour Request place. the coming six months. The cere ater tomornaw. WINES - L14)DOR8 AND BEERS ■aoond lieutenant Merrill B. mony of Installation was In charge Mr. and M ^. John F. Korch of Food At Its Best Such Aa Ravioli. SpMhetU, Chicken and Steaka. ' ^ W bow of 19J East Center street, The public is invited to attend of District Deputy Grand Master S9 Middle Turnh^e West will alao Orders Made Up To 'fake Out i'BMUBleal Warfare Reserve, has the setback party to be held at Clarence Bengston and his staff. -

2018 GSOC Highest Awards Girl Scout Yearbook

Melanoma Recognizing Orange County 2018 Highest Awards Girl Scouts: Bronze Award Girl Scouts, Silver Award Girl Scouts, and Gold Award Girl Scouts Earned between October 2017 - September 2018 1 The Girl Scout Gold Award The Girl Scout Gold Award is the highest and most prestigious award in the world for girls. Open to Girl Scouts in high school, this pinnacle of achievement recognizes girls who demonstrate extraordinary leadership by tackling an issue they are passionate about – Gold Award Girl Scouts are community problem solvers who team up with others to create meaningful change through sustainable and measurable “Take Action” projects they design to make the world a better place. Since 1916, Girl Scouts have been making meaningful, sustainable changes in their communities and around the world by earning the Highest Award in Girl Scouting. Originally called the Golden Eagle of Merit and later, the Golden Eaglet, Curved Bar, First Class, and now the Girl Scout Gold Award, this esteemed accolade is a symbol of excellence, leadership, and ingenuity, and a testament to what a girl can achieve. Girl Scouts who earn the Gold Award distinguish themselves in the college admissions process, earn scholarships from a growing number of colleges and universities across the country, and immediately rise one rank in any branch of the U.S. military. Many have practiced the leaderships skills they need to “go gold” by earning the Girl Scout Silver Award, the highest award for Girl Scout Cadettes in grade 6-8, and the Girl Scout Bronze Award, the highest award for Girl Scout Juniors in grades 4-5. -

“The Social Cut of Black and Yellow Female Hip Hop” Erick Raven

“The Social Cut of Black and Yellow Female Hip Hop” Erick Raven University of Texas at Arlington May 2020 Abstract Korean female hip hop artists are expanding the definition of femininity in South Korea through hip hop. In doing so, they are following a tradition first established by Black female musical performers in a new context. Korean artists are conceiving and expressing, through rap and dance, alternative versions of a “Korean woman,” thus challenging and attempting to add to the dominant conceptions of “woman.” This Thesis seeks to point out the ways female Korean hip hop artists are engaging dominant discourse regarding skin tone, body type, and expression of female sexuality, and creating spaces for the development of new discourses about gender in South Korean society. Contents Introduction – Into the Cut ................................................ 1 Chapter I – Yoon Mi-rae and Negotiating the West and East of Colorism ............................................................. 12 Chapter II – The Performing Black and Yellow Female Body ................................................................................ 31 Chapter III – Performing Sexuality ................................. 47 Chapter IV – Dis-Orientation .......................................... 59 Conclusion .................................................................... 67 Works Cited .................................................................... 70 Introduction – Into the Cut Identities are performed discourse; they are formed when those who identify as a particular personality perform and establish a discourse in a particular social context. As George Lipsitz states, “improvisation is a site of encounter” (61). In South Korea, female Korean hip hop is the site of a social cut in dominant culture and has become a space of improvisation where new, counter-hegemonic identities are constructed and performed. In this Thesis, I argue that Korean female hip hop artists are enacting a social rupture by performing improvised identities. -

Hip-Hop and Cultural Interactions: South Korean and Western Interpretations

HIP-HOP AND CULTURAL INTERACTIONS: SOUTH KOREAN AND WESTERN INTERPRETATIONS. by Danni Aileen Lopez-Rogina, B.A. A thesis submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a Major in Sociology May 2017 Committee Members: Nathan Pino, Chair Rachel Romero Rafael Travis COPYRIGHT by Danni Aileen Lopez-Rogina 2017 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Danni Aileen Lopez-Rogina, refuse permission to copy in excess of the “Fair Use” exemption without my written permission. DEDICATION To Frankie and Holly for making me feel close to normal. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to acknowledge my mom, dad, and sister first and foremost. Without their love and support over the years, I would not have made it this far. They are forever my cheerleaders, no matter how sassy I may be. Professor Nathan Pino was my chosen mentor who took me under his wing when I chose him like a stray cat. His humor and dedication to supporting me helped me keep my head up even when I felt like I was drowning. Professor Rachel Romero was the one to inspire me to not only study sociology, but also to explore popular culture as a key component of society.