University of Westminster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St Marylebone Parish Church Records of Burials in the Crypt 1817-1853

Record of Bodies Interred in the Crypt of St Marylebone Parish Church 1817-1853 This list of 863 names has been collated from the merger of two paper documents held in the parish office of St Marylebone Church in July 2011. The large vaulted crypt beneath St Marylebone Church was used as place of burial from 1817, the year the church was consecrated, until it was full in 1853, when the entrance to the crypt was bricked up. The first, most comprehensive document is a handwritten list of names, addresses, date of interment, ages and vault numbers, thought to be written in the latter half of the 20th century. This was copied from an earlier, original document, which is now held by London Metropolitan Archives and copies on microfilm at London Metropolitan and Westminster Archives. The second document is a typed list from undertakers Farebrother Funeral Services who removed the coffins from the crypt in 1980 and took them for reburial at Brookwood cemetery, Woking in Surrey. This list provides information taken from details on the coffin and states the name, date of death and age. Many of the coffins were unidentifiable and marked “unknown”. On others the date of death was illegible and only the year has been recorded. Brookwood cemetery records indicate that the reburials took place on 22nd October 1982. There is now a memorial stone to mark the area. Whilst merging the documents as much information as possible from both lists has been recorded. Additional information from the Farebrother Funeral Service lists, not on the original list, including date of death has been recorded in italics under date of interment. -

Advice to Inform Post-War Listing in Wales

ADVICE TO INFORM POST-WAR LISTING IN WALES Report for Cadw by Edward Holland and Julian Holder March 2019 CONTACT: Edward Holland Holland Heritage 12 Maes y Llarwydd Abergavenny NP7 5LQ 07786 954027 www.hollandheritage.co.uk front cover images: Cae Bricks (now known as Maes Hyfryd), Beaumaris Bangor University, Zoology Building 1 CONTENTS Section Page Part 1 3 Introduction 1.0 Background to the Study 2.0 Authorship 3.0 Research Methodology, Scope & Structure of the report 4.0 Statutory Listing Part 2 11 Background to Post-War Architecture in Wales 5.0 Economic, social and political context 6.0 Pre-war legacy and its influence on post-war architecture Part 3 16 Principal Building Types & architectural ideas 7.0 Public Housing 8.0 Private Housing 9.0 Schools 10.0 Colleges of Art, Technology and Further Education 11.0 Universities 12.0 Libraries 13.0 Major Public Buildings Part 4 61 Overview of Post-war Architects in Wales Part 5 69 Summary Appendices 82 Appendix A - Bibliography Appendix B - Compiled table of Post-war buildings in Wales sourced from the Buildings of Wales volumes – the ‘Pevsners’ Appendix C - National Eisteddfod Gold Medal for Architecture Appendix D - Civic Trust Awards in Wales post-war Appendix E - RIBA Architecture Awards in Wales 1945-85 2 PART 1 - Introduction 1.0 Background to the Study 1.1 Holland Heritage was commissioned by Cadw in December 2017 to carry out research on post-war buildings in Wales. 1.2 The aim is to provide a research base that deepens the understanding of the buildings of Wales across the whole post-war period 1945 to 1985. -

Unlocking Potential What’S in This Report

Great Portland Estates plc Annual Report 2013 Unlocking potential What’s in this report 1. Overview 3. Financials 1 Who we are 68 Group income statement 2 What we do 68 Group statement of comprehensive income 4 How we deliver shareholder value 69 Group balance sheet 70 Group statement of cash flows 71 Group statement of changes in equity 72 Notes forming part of the Group financial statements 93 Independent auditor’s report 95 Wigmore Street, W1 94 Company balance sheet – UK GAAP See more on pages 16 and 17 95 Notes forming part of the Company financial statements 97 Company independent auditor’s report 2. Annual review 24 Chairman’s statement 4. Governance 25 Our market 100 Corporate governance 28 Valuation 113 Directors’ remuneration report 30 Investment management 128 Report of the directors 32 Development management 132 Directors’ responsibilities statement 34 Asset management 133 Analysis of ordinary shareholdings 36 Financial management 134 Notice of meeting 38 Joint ventures 39 Our financial results 5. Other information 42 Portfolio statistics 43 Our properties 136 Glossary 46 Board of Directors 137 Five year record 48 Our people 138 Financial calendar 52 Risk management 139 Shareholders’ information 56 Our approach to sustainability “Our focused business model and the disciplined execution of our strategic priorities has again delivered property and shareholder returns well ahead of our benchmarks. Martin Scicluna Chairman ” www.gpe.co.uk Great Portland Estates Annual Report 2013 Section 1 Overview Who we are Great Portland Estates is a central London property investment and development company owning over £2.3 billion of real estate. -

Document.Pdf

6,825 SQ FT OF NEWLY REFURBISHED FIRST FLOOR OFFICE SPACE Introducing 6,825 sq ft of newly refurbished, bright open plan office accommodation overlooking leafy Cavendish Square. CONVENIENTLY LOCATED WITH QUICK ACCESS ACROSS CENTRAL LONDON Oxford Circus Commissionaire Shower Newly Raised access 2 mins walk facilities and refurbished flooring WC spacious WCs to Cat A Bond Street* FLOOR PLAN 7 mins walk WC 6,825 sq ft Goodge Street 11 mins walk 643.06 sq m Suspended 3.4m floor to Excellent Fitted ceiling ceiling height natural light kitchenette *Elizabeth Line opens 2018 19 LOCAL AMENITIES NEW CAVENDISH STREET 15 1. The Wigmore 2. The Langham HARLEY STREET GLOUCESTER PLACE The Wallace 18 BBC 3. The Riding House Café Collection Broadcasting PORTLAND PLACE 6 House MARYLEBONE HIGH STREET 4. Pollen St Social BAKER STREET QUEEN ANNE STREET MANCHESTER SQUARE 5. Beast 19 2 3 10 PORTMAN SQUARE 8 MARYLEBONE LANE 1 6. The Ivy Café 16 7 17 7. Les 110 de Taillevent WIGMORE STREET CAVENDISH PLACE STREET CHANDOS 8. Cocoro Marble CAVENDISH Arch SQUARE 9. Swingers 14 19 11 HENRIETTA PLACE MARGARET STREET 10. Kaffeine DUKE STREET 9 11. Selfridges OXFORD STREET Bond Street 13 12. Carnaby St OXFORD STREET 5 13. John Lewis Oxford 14. St Christopher’s Place Circus PARK STREET REGENT STREET 15. Daylesford Bonhams NEW BOND STREET HANOVER SQUARE 16. Sourced Market GROSVENOR SQUARE BROOK STREET HANOVER STREET DAVIES STREET DAVIES 4 Liberty 17. Psycle GROSVENOR SQUARE 12 18. Third Space Marylebone MADDOX STREET 19. Q Park TERMS FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Sublease available until Matt Waugh Ed Arrowsmith December 2022 0207 152 5515 020 7152 5964 07912 977 980 07736 869 320 Rent on application [email protected] [email protected] Cushman & wakefield copyright 2018. -

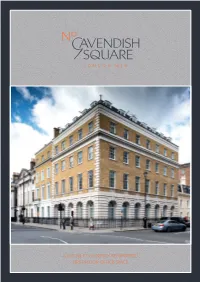

Cavendish Square London W1

CAVENDISH SQUARE LONDON W1 An elegant eight storey Edwardian building, overlooking one of London’s most eminent garden squares in the heart of the West End Executive Summary • Prestigious freehold investment opportunity with significant future development potential • An elegant eight storey Edwardian building overlooking one of London’s most eminent garden squares in the heart of the West End • Currently utilised by a mix of residential and commercial uses • The property comprises approximately: - 5,254.8 sq m (56,562 sq ft) net internal area of commercial space, including office (B1) and medical (D1) - 689.1 sq m (7,419sq ft) gross internal area of residential space • Prime location close to Oxford Street and Mayfair as well as Harley Steet and Portman Square • The building is let to 17 tenants, generating a net income of £2,397,145 per annum. Full vacant possession is available in December 2015 • Significant opportunity to explore a high quality residential or office redevelopment, as well as conversion to full D1 use, subject to the usual consents • Offers sought in excess of £60,000,000 (Sixty Million Pounds) for our client’s freehold interest. A purchase at this level reflects a net initial yield of 3.78% and a capital value of £951 per sq ft assuming standard purchaser’s costs of 5.8% Prominently Situated Hyde Park Marble Arch Park Lane Portman Square Grosvenor Square Manchester Square Oxford Street Wigmore Street Bond Street Harley Street Hanover Square Cavendish Square Regent Street Oxford Circus Location Situation Cavendish Square is one of Central London’s most prestigious garden squares located just north of Oxford Circus, in the heart of London’s West End. -

Career Development Centre Volunteering Stories 2015/16

CAREER DEVELOPMENT CENTRE VOLUNTEERING STORIES 2015/16 1 CONTENTS WELCOME .......................................................................... 4 ABOUT THE GRADUATE ATTRIBUTES .................................... 5 CASE STUDIES GLOBAL IN OUTLOOK AND COMMUNITY ENGAGED ....... 6 JOHANNA LIPPONEN RAGHAD MARDINI SANUSI DRAMMEH SOCIALLY, ETHICALLY AND ENVIRONMENTALLY AWARE ... 12 HASSAN HAKEEM HELPING HOMELESS HUMANS (TRIPLE H) RACHEL LANDSBERG LITERATE AND EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATOR ...................... 18 HUSSAIN TAWANAEE KIU SUM METTE HYLLESTED AMY BROWN ENTREPRENEURIAL .......................................................... 26 ANIL RAI OMAR MAJID RORY SADLER CRITICAL AND CREATIVE THINKER .................................... 32 ANDREW SCARBOROUGH COURTNEY STORY ABOUT OUR SERVICES ........................................................ 38 CONTACT US ..................................................................... 42 2 3 WELCOME TO VOLUNTEERING ABOUT THE IN WESTMINSTER GRADUATE ATTRIBUTES It gives me enormous pride to introduce these Helping Homeless Humans (Triple H), At the University of Westminster we want The five Graduate Attributes, along with a short stories to you. Stories of students just like co-founded by Merlvin, Otis, Abby and our students to have a distinctive learning description of some of their key elements, are you who, through volunteering, have made Katlyn, is a university-wide student initiative to experience. To help create this experience, our listed below. Every volunteering opportunity significant contributions not only to their own support the homeless in London, which raised curriculum is shaped around five key ‘Graduate can help you gain many, if not all, of these development but also for the benefit of society over £500 in one evening. Attributes’ – areas of personal and professional attributes. Some volunteering roles will help you and the creation of a better world for us all. development in which Westminster graduates to develop particular strengths in certain areas. The creativity of your fellow students knows will excel. -

The Architecture of James Stirling and His Partners James Gowan and Michael Wilford

THE ARCHITECTURE OF JAMES STIRLING AND HIS PARTNERS JAMES GOWAN AND MICHAEL WILFORD For my grandchildren, Michelle, Alex, Abigail and Zachary THE ARCHITECTURE OF JAMES STIRLING AND HIS PARTNERS JAMES GOWAN AND MICHAEL WILFORD A Study of Architectural Creativity in the Twentieth Century GEOFFREY H. BAKER First published 2011 by Ashgate Publishing Published 2016 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Copyright © 2011 Geoffrey H. Baker Geoffrey H. Baker has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. The author and publisher gratefully acknowledge the permission granted to reproduce the copyright material in this book. Every effort has been made to trace and to obtain all permissions for the use of copyright material. Due to the manner in which some images have been sourced over a number of years, it has not been possible to record the source of every image or to include full reference details. The publisher apologizes for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book. -

Chapter 5 242–276 Oxford Street John Prince's Street to Holles Street

DRAFT Chapter 5 242–276 Oxford Street John Prince’s Street to Holles Street A block-size commercial development dating from 1959–63 dominates this section of Oxford Street today, stretching back to encompass frontages facing John Prince’s and Holles Streets and half the south side of Cavendish Square. Very typical for its period, it consists mostly of offices and shops. The presence of the London College of Fashion over the Oxford Street front adds a dash of more adventurous architecture. Early history This was among the first sections of the Cavendish-Harley estate to attract building, early in the reign of George I. In connection with the plan to begin that development in and round Cavendish Square, the whole block was leased in 1719 by the Cavendish-Harley trustees to John Prince, so-called master builder, and the Estate’s steward, Francis Seale. But Seale soon died, and Prince’s ambitions seem to have gone unrealized, though he was still active in the 1730s. As a result it took the best part of two decades for the block to be completed by the usual variety of building tradesmen.1 An undated plan shows the layout as first completed, with the apportionment of property between Seale’s executors and Prince apparently indicated. The first development along the frontage may have been inhibited by existing buildings around Nibbs’s Pound at the corner of John Prince’s Street (Princes Street until 1953); it seems that the pound continued in Survey of London © Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London Website: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/architecture/research/survey-london 1 DRAFT existence for some years thereafter, though eventually the Nibbs name was transferred to the pound at the bottom of Marylebone Lane. -

Cavendish Square

DRAFT CHAPTER 7 Cavendish Square Peering over the railings and through the black trees into the garden of the Square, you see a few miserable governesses with wan-faced pupils wandering round and round it, and round the dreary grass-plot in the centre of which rises the statue of Lord Gaunt, who fought at Minden, in a three- tailed wig, and otherwise habited like a Roman Emperor. Gaunt House occupies nearly a side of the Square. The remaining three sides are composed of mansions that have passed away into dowagerism; – tall, dark houses, with window-frames of stone, or picked out of a lighter red. Little light seems to be behind those lean, comfortless casements now: and hospitality to have passed away from those doors as much as the laced lacqueys and link-boys of old times, who used to put out their torches in the blank iron extinguishers that still flank the lamps over the steps. Brass plates have penetrated into the square – Doctors, the Diddlesex Bank Western Branch – the English and European Reunion, &c. – it has a dreary look. Thackeray made little attempt to disguise Cavendish Square in Vanity Fair (1847–8). Dreariness could not be further from what had been intended by those who, more than a century earlier, had conceived the square as an enclave of private palaces and patrician grandeur. Nor, another century and more after Thackeray, is it likely to come to mind in what, braced between department stores and doctors’ consulting rooms, has become an oasis of smart offices, sleek subterranean parking and occasional lunch-hour sunbathing. -

Permanencias En La Arquitectura De James Stirling Tesis Doctoral

Universidad Politécnica de Madrid Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura Permanencias en la arquitectura de James Stirling Tesis doctoral José María Silva Hernández-Gil Arquitecto 2015 Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid Departamento de Proyectos Arquitectónicos Permanencias en la arquitectura de James Stirling Tesis doctoral Autor José María Silva Hernández-Gil Arquitecto Director José Manuel López-Peláez Morales Doctor arquitecto 2015 Universidad Politécnica de Madrid Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura Tribunal nombrado por el Magnífico y Excelentísimo Sr. Rector de la Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, el día . de . de 2015. Presidente D. Vocal D. Vocal D. Vocal D. Secretario D. Realizado el acto de defensa y lectura de la Tesis Permanencias en la arquitectura de James Stirling el día . de . de 2015, en Madrid. Calificación: El Presidente Los Vocales El Secretario Índice Permanencias en la arquitectura de James Stirling Agradecimientos 5 Resumen / Abstract 7 Introducción 13 Método 17 Estructura 19 Preliminares 23 Estado de la cuestión 25 Marco crítico 33 Cronología gráfica 53 Tesis 65 I. Expresión del orden 67 1. El orden de la función 72 1.1. Newton Aycliffe 79 1.2. Stiff Dom-ino 81 1.3. Sheffield 83 1.4. House Studies 85 2. El orden del tipo 88 2.1. Village Project 92 2.2. Preston 94 2.3. Churchill 96 2.4. Leicester 99 3. El orden del lugar 102 3.1. Cambridge 107 3.2. Oxford 109 III. Movimiento y territorio 187 3.3. Runcorn 111 1. Movimientos modernos 192 3.4. Derby 113 1.1. Paralaje y secuencia visual 192 4. El orden del fragmento 115 1.2. -

Planning, Design and Access Statement Underbelly Cavendish Square

Planning, Design and Access Statement Underbelly Cavendish Square APRIL 2021 Q210207 Contents 1 Introduction ______________________________________________________________ 1 2 Site and Surrounding Area __________________________________________________ 3 3 Planning Policy Overview ___________________________________________________ 6 4 The Proposals ___________________________________________________________ 13 5 Design and Access _______________________________________________________ 16 6 Key Planning Considerations ________________________________________________ 18 7 Conclusions _____________________________________________________________ 22 Figure 1 Proposed Site Plan ______________________________________________________ 14 No table of figures entries found. Quod | Underbelly Cavendish Square | Planning, Design and Access Statement | April 2021 1 Introduction 1.1 This Planning Statement has been prepared by Quod in support of an application for planning permission and advertisement consent, submitted to Westminster City Council (‘WCC’) on behalf of Underbelly Limited (‘the Applicant’). In summary, this submission seeks consent for the following: • Temporary planning permission for a Spiegeltent touring structure, a box office, a bar area, 8 catering units, toilets, storage, outdoor seating areas and fencing in conjunction with Underbelly Summer Event 2021 on Cavendish Square over the Summer period (14 June 2021 – 8 October 2021); and • Temporary advertisement consent for associated signage for the pop-up Summer Event for the same time period identified above, which include all installation and de-installation periods. 1.2 The application site comprises the open space at Cavendish Square, Marylebone, London, W1G 0PR (‘the Site’), which is located a short distance north of Oxford Street and west of Regent Street. The site is bound on all four sides by a mix of office, commercial, health and education uses. The Applicant 1.3 Underbelly is a UK based live entertainment company and its festival and events division produce numerous annual events. -

Career Development Centre Cvs, Application Forms, Covering Letters

CAREER DEVELOPMENT CENTRE CVS, APPLICATION FORMS, COVERING LETTERS EXPERIENCE EXPERTISE EXCELLENCE CONTENTS CAREER DEVELOPMENT CENTRE ...............................3 Find out about our services and get the latest careers advice and support to maximise your employability. CVs ....................................................................... 11 Everything you need to know about writing a winning CV – targeting your CV, getting the format right, what to include, examples and top tips. COVERING LETTERS ................................................... 25 Find out how to write a successful covering letter with our step-by-step guidelines and examples. APPLICATION FORMS ............................................. 31 Discover what it takes to ensure your application form stands out from the crowd. MANAGING YOUR ONLINE PRESENCE .................. 37 Advice and tips on managing your social media presence online and keeping your private life private. THE POWER OF VOCABULARY ................................ 41 Find out what power words you could use to express your skills and experience. CONTACT US ........................................................ 44 This booklet is available in alternative formats upon request. A web version is also available at westminster.ac.uk/careers The different formats would be by special request via disability services. 1 2 LOP EVE ME D N R T E C E E R N A T R C E 3 ABOUT We can assist with: We have a team of friendly • Sourcing vacancies career professionals who are • Developing employability in touch with employers on a skills daily basis to provide you with • Identifying key skills and up-to-date current employment experiences trends, and job vacancies. We • Planning your professional also provide guidance and development information on further study and training opportunities. • Presenting a positive image: how to market yourself effectively.