Chapter 8: South of Cavendish Square

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St Marylebone Parish Church Records of Burials in the Crypt 1817-1853

Record of Bodies Interred in the Crypt of St Marylebone Parish Church 1817-1853 This list of 863 names has been collated from the merger of two paper documents held in the parish office of St Marylebone Church in July 2011. The large vaulted crypt beneath St Marylebone Church was used as place of burial from 1817, the year the church was consecrated, until it was full in 1853, when the entrance to the crypt was bricked up. The first, most comprehensive document is a handwritten list of names, addresses, date of interment, ages and vault numbers, thought to be written in the latter half of the 20th century. This was copied from an earlier, original document, which is now held by London Metropolitan Archives and copies on microfilm at London Metropolitan and Westminster Archives. The second document is a typed list from undertakers Farebrother Funeral Services who removed the coffins from the crypt in 1980 and took them for reburial at Brookwood cemetery, Woking in Surrey. This list provides information taken from details on the coffin and states the name, date of death and age. Many of the coffins were unidentifiable and marked “unknown”. On others the date of death was illegible and only the year has been recorded. Brookwood cemetery records indicate that the reburials took place on 22nd October 1982. There is now a memorial stone to mark the area. Whilst merging the documents as much information as possible from both lists has been recorded. Additional information from the Farebrother Funeral Service lists, not on the original list, including date of death has been recorded in italics under date of interment. -

Unlocking Potential What’S in This Report

Great Portland Estates plc Annual Report 2013 Unlocking potential What’s in this report 1. Overview 3. Financials 1 Who we are 68 Group income statement 2 What we do 68 Group statement of comprehensive income 4 How we deliver shareholder value 69 Group balance sheet 70 Group statement of cash flows 71 Group statement of changes in equity 72 Notes forming part of the Group financial statements 93 Independent auditor’s report 95 Wigmore Street, W1 94 Company balance sheet – UK GAAP See more on pages 16 and 17 95 Notes forming part of the Company financial statements 97 Company independent auditor’s report 2. Annual review 24 Chairman’s statement 4. Governance 25 Our market 100 Corporate governance 28 Valuation 113 Directors’ remuneration report 30 Investment management 128 Report of the directors 32 Development management 132 Directors’ responsibilities statement 34 Asset management 133 Analysis of ordinary shareholdings 36 Financial management 134 Notice of meeting 38 Joint ventures 39 Our financial results 5. Other information 42 Portfolio statistics 43 Our properties 136 Glossary 46 Board of Directors 137 Five year record 48 Our people 138 Financial calendar 52 Risk management 139 Shareholders’ information 56 Our approach to sustainability “Our focused business model and the disciplined execution of our strategic priorities has again delivered property and shareholder returns well ahead of our benchmarks. Martin Scicluna Chairman ” www.gpe.co.uk Great Portland Estates Annual Report 2013 Section 1 Overview Who we are Great Portland Estates is a central London property investment and development company owning over £2.3 billion of real estate. -

NEWSLETTER Parish of St George Hanover Square St George’S Church Grosvenor Chapel March—June 2015: Issue 30

NEWSLETTER Parish of St George Hanover Square St George’s Church Grosvenor Chapel March—June 2015: issue 30 ence these men exercised on Inside this issue musical life in the second half of the twentieth century: The Rector writes 2 Christopher Morris, the prodi- gious Anglican church musi- Services at St George’s 3 cian and organist of distinc- tion who befriended and Fr Richard Fermer writes 6 mentored a generation of Eng- lish, Welsh and Scottish com- Services at Grosvenor Chapel 7 posers and whose immensely practical publisher’s mind Lent Course 8 conceived and gave birth to Prisons Mission 10 that ubiquitous staple of An- glophone choirs worldwide, London Handel Festival 11 Carols for Choirs; and Denys Darlow who not only founded Mayfair Organ Concerts 13 major English festivals cele- brating the music of Bach and Hyde Park Place Estate Charity 15 Handel but who played a pro- found part, through his per- t is with great sadness that we formances of works by these I learned, just as this edition of Baroque masters and their the Parish Newsletter was going contemporaries, in our devel- to press, of the death at the age oping understanding of ‘early of 93 of Denys Darlow who served music’. as tenth organist and choirmaster of St George’s between 1972 and This year’s London Handel 2000. It is just two months since Festival - an annual event the demise of Darlow’s younger Darlow founded at St George’s predecessor, Christopher Morris back in 1978 - is about to (organist between 1947 and start. -

National Sample from the 1851 Census of Great Britain List of Sample Clusters

NATIONAL SAMPLE FROM THE 1851 CENSUS OF GREAT BRITAIN LIST OF SAMPLE CLUSTERS The listing is arranged in four columns, and is listed in cluster code order, but other orderings are available. The first column gives the county code; this code corresponds with the county code used in the standardised version of the data. An index of the county codes forms Appendix 1 The second column gives the cluster type. These cluster types correspond with the stratification parameter used in sampling and have been listed in Background Paper II. Their definitions are as follows: 11 English category I 'Communities' under 2,000 population 12 Scottish category I 'Communities' under 2,000 population 21 Category IIA and VI 'Towns' and Municipal Boroughs 26 Category IIB Parliamentary Boroughs 31 Category III 'Large non-urban communities' 41 Category IV Residual 'non-urban' areas 51 Category VII Unallocable 'urban' areas 91 Category IX Institutions The third column gives the cluster code numbers. This corresponds to the computing data set name, except that in the computing data set names the code number is preceded by the letters PAR (e.g. PAR0601). The fourth column gives the name of the cluster community. It should be noted that, with the exception of clusters coded 11,12 and 91, the cluster unit is the enumeration district and not the whole community. Clusters coded 11 and 12, however, correspond to total 'communities' (see Background Paper II). Clusters coded 91 comprise twenty successive individuals in every thousand, from a list of all inmates of institutions concatenated into a continuous sampling frame; except that 'families' are not broken, and where the twenty individuals come from more than one institution, each institution forms a separate cluster. -

NEWSLETTER Parish of St George Hanover Square

NEWSLETTER Parish of St George Hanover Square St George’s Church Grosvenor Chapel November 2016-February 2017 Issue 35 A computer-generated visualisation of the new St George’s Undercroft derived from the architect’s plans. ther contributions not- we raised £5,000 as part of a Inside this issue withstanding, two con- Christian Aid partnership pro- trasting matters domi- ject which, because of a triple The Rector writes 2 O nate this issue of the funding arrangement with the Organ Concerts 3 Parish Newsletter: on the one EU, resulted in £20,000 going to hand plans to bring St George’s support maternity and child Services at St George’s 4 Undercroft back into parish use health care in Kenya. More Assistant Director of Music 6 and, on the other, the further modestly the needs of a parish development of a prisons mis- in Botswana run by a former The Undercroft 7 sion, now adopted by Churches Parish Administrator of St Services at Grosvenor Chapel 10 Together in Westminster, but George’s were met within days driven by an indefatigable mem- of the publication of the previ- Prisons Mission 11 ber of the St George’s parish ous edition of this Newsletter community. John Plummer and which highlighted the need in Hyde Park Place Charity 15 Sarah Jane Vernon’s pieces on question. Contacts 16 the 2016 Prisons Week speak for themselves but they illustrate a And so we come to the question Not that one has to visit Worm- willingness by parishioners to of UK prisons, not of prison re- wood Scrubs or Pentonville to en- engage with matters outside the form but of a wish to engage counter those at odds with socie- obvious comfort zone of the collaboratively with those who ty. -

Document.Pdf

6,825 SQ FT OF NEWLY REFURBISHED FIRST FLOOR OFFICE SPACE Introducing 6,825 sq ft of newly refurbished, bright open plan office accommodation overlooking leafy Cavendish Square. CONVENIENTLY LOCATED WITH QUICK ACCESS ACROSS CENTRAL LONDON Oxford Circus Commissionaire Shower Newly Raised access 2 mins walk facilities and refurbished flooring WC spacious WCs to Cat A Bond Street* FLOOR PLAN 7 mins walk WC 6,825 sq ft Goodge Street 11 mins walk 643.06 sq m Suspended 3.4m floor to Excellent Fitted ceiling ceiling height natural light kitchenette *Elizabeth Line opens 2018 19 LOCAL AMENITIES NEW CAVENDISH STREET 15 1. The Wigmore 2. The Langham HARLEY STREET GLOUCESTER PLACE The Wallace 18 BBC 3. The Riding House Café Collection Broadcasting PORTLAND PLACE 6 House MARYLEBONE HIGH STREET 4. Pollen St Social BAKER STREET QUEEN ANNE STREET MANCHESTER SQUARE 5. Beast 19 2 3 10 PORTMAN SQUARE 8 MARYLEBONE LANE 1 6. The Ivy Café 16 7 17 7. Les 110 de Taillevent WIGMORE STREET CAVENDISH PLACE STREET CHANDOS 8. Cocoro Marble CAVENDISH Arch SQUARE 9. Swingers 14 19 11 HENRIETTA PLACE MARGARET STREET 10. Kaffeine DUKE STREET 9 11. Selfridges OXFORD STREET Bond Street 13 12. Carnaby St OXFORD STREET 5 13. John Lewis Oxford 14. St Christopher’s Place Circus PARK STREET REGENT STREET 15. Daylesford Bonhams NEW BOND STREET HANOVER SQUARE 16. Sourced Market GROSVENOR SQUARE BROOK STREET HANOVER STREET DAVIES STREET DAVIES 4 Liberty 17. Psycle GROSVENOR SQUARE 12 18. Third Space Marylebone MADDOX STREET 19. Q Park TERMS FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Sublease available until Matt Waugh Ed Arrowsmith December 2022 0207 152 5515 020 7152 5964 07912 977 980 07736 869 320 Rent on application [email protected] [email protected] Cushman & wakefield copyright 2018. -

Shops Aug 2012

1 SHOPS Shops Among London’s main attractions are the long streets full of shops, some of which are famous throughout the world. All of those listed here were visited during 2011. Our survey teams found that access to shops has improved considerably in recent years. In particular there are fewer split levels, more accessible toilets, and more BCF. However, few have textphone details on their website and there are still a small number with unexpected split levels. Importantly, attitudes have changed, and staff members are more often understanding of special needs than was the case ten years ago. In this chapter we have concentrated mainly on the Oxford Street/Regent Street area, as well as including famous shops like Harrods, Harvey Nichols, Peter Jones and Fortnum and Mason. We have also included a few shops on Kensington High Street, and around Victoria. We have only visited and described a tiny percentage of London’s shops, so please do not be limited by listings in this section. Nearly all the big shops we have described have accessible toilets. Access is generally good, although the majority of the big stores have central escalators. The lifts are less obvious and may even be slightly difficult to find. Signage is highly variable. Most big department stores have a store guide/listing near the main entrance, or at the bottom of escalators, but these do not normally take account of access issues. A few have printed plans of the layout of each floor (which may be downloadable from their website), but these aren’t always very clear or accurate. -

Marylebone Lane Area

DRAFT CHAPTER 5 Marylebone Lane Area At the time of its development in the second half of the eighteenth century the area south of the High Street was mostly divided between three relatively small landholdings separating the Portman and Portland estates. Largest was Conduit Field, twenty acres immediately east of the Portman estate and extending east and south to the Tyburn or Ay Brook and Oxford Street. This belonged to Sir Thomas Edward(e)s and later his son-in-law John Thomas Hope. North of that, along the west side of Marylebone Lane, were the four acres of Little Conduit Close, belonging to Jacob Hinde. Smaller still was the Lord Mayor’s Banqueting House Ground, a detached piece of the City of London Corporation’s Conduit Mead estate, bounded by the Tyburn, Oxford Street and Marylebone Lane. The Portland estate took in all the ground on the east side of Marylebone Lane, including the two island sites: one at the south end, where the parish court-house and watch-house stood, the other backing on to what is now Jason Court (John’s Court until 1895). This chapter is mainly concerned with Marylebone Lane, the streets on its east side north of Wigmore Street, and the southern extension of the High Street through the Hinde and part of the Hope–Edwardes estates, in the form of Thayer Street and Mandeville Place – excluding James Street, which is to be described together with the Hope–Edwardes estate generally in a later volume. The other streets east of Marylebone Lane – Henrietta Place and Wigmore Street – are described in Chapters 8 and 9. -

M a R Y L E B O

MARYLEBONE GR A ND, ECCENTR IC, ICONIC. London’s most magnificent private members’ club, fusing 18th century splendour with 21st century style. Established in the 18th Century, Home House was designed by George III’s architect, James Wyatt, who was commissioned to build a sophisticated palace purely for enjoyment and entertainment, as No 20 Portman Square. Today, Home House hosts a collection of characters and individuals spread across three exquisite Georgian townhouses, offering an exceptional range of facilities including restaurants, bars, The Vaults, an intimate garden, elegant bedrooms, a boardroom, a gym and a thriving calendar of exclusive member’s events. A Flamboyant History Robert Adam, one of the most celebrated architects of his day, was appointed in 1775 to complete the building. Home House is acknowledged as Robert Adam’s finest surviving London town house, with one of the most breath-taking imperial staircases in European architecture. The venue of the most illustrious parties of the 18th century high society, the House continues to be a shrine to hedonism today through its legendary member’s parties. EAT AT HOME British Excellence Exquisite British dining is at the heart of Home House. Our talented team of chefs peruse the country for the best possible ingredients, be it for breakfast, lunch, or dinner. Savour the delights of our brasserie-style menu with its great British classics and innovative twists. Enjoy afternoon tea in the splendour of The Drawing Rooms, or a selection of small plates to share in one of our elegant lounges. A truly glamorous backdrop for any type of celebra- tion, we can cater for private events of all kinds, from celebratory wedding feasts to corporate buffets. -

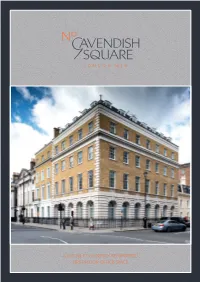

Cavendish Square London W1

CAVENDISH SQUARE LONDON W1 An elegant eight storey Edwardian building, overlooking one of London’s most eminent garden squares in the heart of the West End Executive Summary • Prestigious freehold investment opportunity with significant future development potential • An elegant eight storey Edwardian building overlooking one of London’s most eminent garden squares in the heart of the West End • Currently utilised by a mix of residential and commercial uses • The property comprises approximately: - 5,254.8 sq m (56,562 sq ft) net internal area of commercial space, including office (B1) and medical (D1) - 689.1 sq m (7,419sq ft) gross internal area of residential space • Prime location close to Oxford Street and Mayfair as well as Harley Steet and Portman Square • The building is let to 17 tenants, generating a net income of £2,397,145 per annum. Full vacant possession is available in December 2015 • Significant opportunity to explore a high quality residential or office redevelopment, as well as conversion to full D1 use, subject to the usual consents • Offers sought in excess of £60,000,000 (Sixty Million Pounds) for our client’s freehold interest. A purchase at this level reflects a net initial yield of 3.78% and a capital value of £951 per sq ft assuming standard purchaser’s costs of 5.8% Prominently Situated Hyde Park Marble Arch Park Lane Portman Square Grosvenor Square Manchester Square Oxford Street Wigmore Street Bond Street Harley Street Hanover Square Cavendish Square Regent Street Oxford Circus Location Situation Cavendish Square is one of Central London’s most prestigious garden squares located just north of Oxford Circus, in the heart of London’s West End. -

Career Development Centre Volunteering Stories 2015/16

CAREER DEVELOPMENT CENTRE VOLUNTEERING STORIES 2015/16 1 CONTENTS WELCOME .......................................................................... 4 ABOUT THE GRADUATE ATTRIBUTES .................................... 5 CASE STUDIES GLOBAL IN OUTLOOK AND COMMUNITY ENGAGED ....... 6 JOHANNA LIPPONEN RAGHAD MARDINI SANUSI DRAMMEH SOCIALLY, ETHICALLY AND ENVIRONMENTALLY AWARE ... 12 HASSAN HAKEEM HELPING HOMELESS HUMANS (TRIPLE H) RACHEL LANDSBERG LITERATE AND EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATOR ...................... 18 HUSSAIN TAWANAEE KIU SUM METTE HYLLESTED AMY BROWN ENTREPRENEURIAL .......................................................... 26 ANIL RAI OMAR MAJID RORY SADLER CRITICAL AND CREATIVE THINKER .................................... 32 ANDREW SCARBOROUGH COURTNEY STORY ABOUT OUR SERVICES ........................................................ 38 CONTACT US ..................................................................... 42 2 3 WELCOME TO VOLUNTEERING ABOUT THE IN WESTMINSTER GRADUATE ATTRIBUTES It gives me enormous pride to introduce these Helping Homeless Humans (Triple H), At the University of Westminster we want The five Graduate Attributes, along with a short stories to you. Stories of students just like co-founded by Merlvin, Otis, Abby and our students to have a distinctive learning description of some of their key elements, are you who, through volunteering, have made Katlyn, is a university-wide student initiative to experience. To help create this experience, our listed below. Every volunteering opportunity significant contributions not only to their own support the homeless in London, which raised curriculum is shaped around five key ‘Graduate can help you gain many, if not all, of these development but also for the benefit of society over £500 in one evening. Attributes’ – areas of personal and professional attributes. Some volunteering roles will help you and the creation of a better world for us all. development in which Westminster graduates to develop particular strengths in certain areas. The creativity of your fellow students knows will excel. -

NEWSLETTER Parish of St George Hanover Square

NEWSLETTER Parish of St George Hanover Square St George’s Church Grosvenor Chapel July—October 2016: issue 34 Inside this issue The Rector writes 2 Organ Concerts 3 Services at St George’s 4 Services at Grosvenor Chapel 7 Prisons Mission 8 Parish Officers etc 9 Neighbours 10 St Mark’s Church, Lobatse in the Diocese of Botswana Hyde Park Place Estate Charity 11 s the Rector mentions on now parish priest at St Mark’s, Lo- Africa calling 11 page 2, thanks to the batse in southern Botswana and in generous support of need of funds to enable the parish Contacts 12 A members of the St to purchase a piano. Details may be George’s congregation and wider found on page 11. Please be as gen- took place on Maundy Thursday 1882 family, we have recently honoured erous as you can. when all seems to have been less our pledge to raise £5,000 in sup- than amicable between ourselves Churches Together in Westminster port of a Christian Aid Community and our Salvation Army neighbours features twice between these cov- Partnership project in Kenya. Now on Oxford Street. This came to ers. John Plummer provides an up- light earlier in the year when we have an opportunity to give a date on the CTiW Prisons Mission in Churches Together’s Meet the helping hand a little further south which St George’s has played a pio- Neighbours project invited partici- in Botswana. Links between the St neering role. If you would like to pating churches to visit the Sally George’s Vestry and Southern Af- receive further information or ex- Army’s premises at Regent Hall.