Tutored Wine Tasting Thursday 13Th July 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hallgarten Druitt

Schloss Johannisberg, Rheingau, Riesling Trocken 'Bronze Seal' 2020 Delicate floral aromas of white stone fruits, lime notes, Awards green pears and a touch of minerality lead to a refreshing 95 pts, James Suckling, 2021 and cleansing palate. Classic and expressive dry Riesling. Producer Note The legendary Schloss Johannisberg is steeped in history. The vineyards were planted on the orders of the Roman Emperor Charlemagne. Planted solely with Riesling grapes in 1720, Schloss Johannisberg was the world's first Riesling Estate and plays a significant part in wine history. It was here in 1775 that the Spätlese quality was discovered using late picked grapes suffering from "noble rot". Following this discovery, in 1787 the estate gave Auslese, Beerenauslese and Trockenbeerenauslese to the wine world. Schloss Johannisberg is a single vineyard designation in its own right and one of a handful of German vineyards that does not have to display a village name on the label. Vineyard The grapes come from the single vineyard of Schloss Johannisberg. The south facing vineyard is steep, with a 45° gradient and is situated at between 114 metres to 181 metres above sea level. The forest on the top of the Taunus Mountains protects the vineyard from cold winds from the north. To the south, the River Rhine gently flows in front of the estate, in the foothills of the vineyard. The 50° parallel runs directly through the vineyard and the unique soils of Taunus quartz, topped with loam and rich loess retains moisture and heat, encouraging the vines to ripen. This soil formation imparts the classic mineral characteristic which is evident in this wine. -

European Workshop on Bronchiolitis Obliterans

Practical Information Sponsors Venue Schloss Johannisberg 65366 Geisenheim-Johannisberg www.schloss-johannisberg.de Contact / Registration / Questions European Workshop on [email protected] [email protected] Bronchiolitis obliterans: +49 (0) 69 – 66 98 30 – 24 status quo and future directions Hotel Burg Schwarzenstein (Relais & Château) Rosengasse 32, 65366 Geisenheim-Johannisberg, Tel.: +49 6722 - 99 50 0 Fax: +49 6722 - 99 50 99 E-Mail: [email protected] www.burg-schwarzenstein.de Kloster Johannisberg Benediktus Hort GmbH Badpfad 1, 65366 Geisenheim-Johannisberg Tel: +49 67 22 49 791 0 Fax: +49 67 22 49 791 79 February 10 + 11 , 2017 E-Mail: [email protected] www.kloster-johannisberg.de Schloss Johannisberg, Nearest Intercity Express (ICE) Station 65366 Geisenheim im Rheingau Wiesbaden Hbf Alternative: Frankfurt/M Airport (Fernbahnhof) www.starkelunge.de Friday 10. February 2017 16:15 Quality of life and how to improve it Mandy Niemitz 17:00 The nexus of Inflammation and Nutrition 10 :30 Welcome Hansjosef Böhles 11:00 Summary from the last workshop: What have we learned so far and where do we want to go? Martin Rosewich 20:00 - Get Together - Saturday 11. February 2017 Diagnosing BO Invitation and greetings from the founders 11:30 PiBO: Early Signs and Symptoms in the patient 8:30 Which Therapies work – What Research is needed history Alicia Casey Dear Ladies and Gentlemen, Matthias Griese 12:00 PiBO: Courses of PiBO in adults We invite you to participate in our 2nd European Michael Tamm Thinking about BO Workshop on Bronchiolitis Obliterans (BO). 09:15 Microbiome and the lung - 12:30 - Lunch - does it matter for BO The goal of our foundation is to help children and their Folke Brinkmann families suffering from a rare, chronic lung disease. -

Weinproben Tastings

Weinproben Tastings 11.–12. NOVEMBER 2010 SCHLOSS REINHARTSHAUSEN RHEINGAU Programm Donnerstag,11.November 2010 Seite 9.30 Uhr Willkommen zum IRS 2010 10.00 Uhr Eröffnung des IRS 2010 durch den Schirmherrn, Ministerpräsident Roland Koch 10.30 Uhr Kelterhalle Vortrag David Schildknecht (The Wine Advocate, USA) Riesling und seine Chancen im globalen Markt 11.30 Uhr Pause 11.45 Uhr Festsäle Weinprobe 6–13 Trockene Spitzen-Rieslinge Moderation: Dr. Josef Schuller MW (Chairman/MW, Rust) 13.15 Uhr Lunch 14.00 Uhr Kelterhalle Vortrag Jochen Wissler (Restaurant Vendˆome) Riesling und moderne Kulinarik 15.00 Uhr Pause 15.15 Uhr Festsäle Weinprobe 14–21 Riesling Eleganz mit dezenter Restsüße Moderation: Stéphane Gass (Sommelier, Traube Tonbach) 16.45 Uhr Pause 17.00 Uhr Kelterhalle Vortrag Georg Mauer (Wein & Glas Compagnie, Berlin) Wirtschaftliche Bedeutung der Riesling-Weine im Weinfachhandel 18.00 Uhr Pause 20.00 Uhr Festsäle Walking Wine Dinner mit den Köchen: 39 Frank Buchholz (Restaurant Buchholz, Mainz) Jens Fischer (Restaurant Freundstück, Deidesheim) Kazuya Fukuhira (Die Köche, Eltville) Bernd H. Körber (Schloss Reinhartshausen, Eltville) Harald Rüssel (Landhaus St. Urban, Naurath) und Weinen der Symposiums-Weingüter 2 Freitag,12. November 2010 Seite 9.30 Uhr Kelterhalle Vortrag Dieter Braatz (Chefredaktion DER FEINSCHMECKER) Die Erfolgsstory des Rieslings in den Medien in den letzten zwei Jahrzehnten 10.30 Uhr Pause 10.45 Uhr Festsäle Weinprobe 22–29 Alterungspotential des Rieslings Moderation: Jancis Robinson MW (London) 12.15 Uhr Lunch 13.00 Uhr Kelterhalle Vortrag Dr. Daniel Deckers (Journalist, FAZ) „Grand Cru von deutschem Boden“– Geschichte der Klassifikation 14.00 Uhr Pause 14.15 Uhr Festsäle Weinprobe 30–37 Edelsüße Rieslinge Moderation: Caro Maurer (Journalistin, Bonn) 15.45 Uhr Pause 16.00 Uhr Kelterhalle Vortrag Prof. -

Appetizers Our Homemade Bread

our homemade bread WITH WHITE FLOUR BREAD (BIO) €1,50/PERSON MULTIGRAIN CAROB (BIO) €1,50/PERSON appetizers KATAIFI CHEESE BALLS NEW €7,50 WITH KOPANISTI MYKONOU (SALTY & SPICY CHEESE), HONEY AND NIGELLA SEEDS ZUCCHINI BALLS €7,50 WITH YOGHURT MOUSSE TRIPLE-FRIED NAXOS POTATOES • WITH OREGANO AND THYME €5,50 • WITH EGGS OVER EASY, FETA CHEESE CREAM AND €8,50 SINGLINO FROM MANI (SMOKED SALTED PORK) OVEN BAKED VEAL MEATBALLS NEW €9,00 WITH TOMATO MARMALADE PASTRAMI ROLLS NEW €7,50 PASTRAMI FROM DRAMA IN A BAKED ROLL WITH TOMATO SAUCE AND KASSERI (TRADITIONAL CHEESE) FROM XANTHI OUR DELICACIES PLATTER €12,50 SALAMI FROM LEFKADA, PROSCIUTTO FROM DRAMA, SINGLINO FROM MANI, KOPANISTI FROM MYKONOS, KASSERI FROM XANTHI, ARSENIKO FROM NAXOS, DRIED FRUITS AND CHERRY TOMATOES SPETZOFAI NEW €9,50 WITH SPICY SAUSAGE FROM DRAMA AND GRILLED FLORINA PEPPERS SXINOUSA'S FAVA NEW €12,50 SPLIT PEAS WIITH CAPER SALAD, SUN DRIED TOMATOES, OLIVES AND CHERRY TOMATOES MARINATED HORNBEAM TART NEW €11,00 WITH GREEN SALAD, SUN DRIED TOMATOES AND TARAMA (FISH ROE) SALAD CREAM BREADED EGGS NEW €7,00 WITH CRUNCHY CRUST AND SAUT�ED GREENS www.kiouzin.com REGULAR salads ONE PERSON WILD FOREST MUSHROOMS WITH PLEUROTUS €10,50 €7,50 MEDITERRANEAN SPAGHETTI NEW €8,50 MUSHROOMS, CREAM CHEESE TRUFFLES AND FRESH WITH FRESH TOMATO, ONION, OLIVES AND CAPERS GOJI BERRIES, GREEN AND RED LOLA, BABY SPINACH AND BABY ROCA, PARSLEY, MULTICOLOR PEPPERS,CHERRY SPAGHETTI WITH MESOLONGI FISH ROE, €16,50 TOMATOES AND A VINAIGRETTE PETIMEZI (GRAPE SYRUP) WITH BASIL AND CHERRY TOMATOES SUPERFOODS -

Rieslings Since 1720 Schloss Johannisberg Is Celebrating “300 Years of Riesling”

Press release Rieslings since 1720 Schloss Johannisberg is celebrating “300 Years of Riesling” Schloss Johannisberg in the Rheingau region is the first Riesling estate in the world and now combines nearly 1,200 years of wine-making history with exactly 300 years of world-class Riesling tradition. The estate with the oldest single- variety Riesling vineyard wants to celebrate this anniversary year with a varied programme of events and, in the second half of the year, also plans to invite visitors to celebrate the popular grape and its many exceptional Riesling wines together. Exclusive Riesling grower since 1720 The Schloss Johannisberg estate can look back on an eventful history that has resulted in a unique wine-making culture: Established as a Benedictine monastery in around 1100, the Johannisberger Abbey quickly became the focal point and initiator of wine-growing in the Rheingau region. In 1716, the already famous but neglected vineyard was passed to the Princely Abbey of Fulda under Prince Abbot Konstantin von Buttlar, who revitalised it from the ground up and attempted a major viticultural experiment: He replanted the estate’s vineyards with only the noblest grape in the world, the Riesling. Around 300,000 new vines were planted over the following two years. This is how the world’s first cohesive Riesling vineyard was created in 1720. Real gems from 300 years of Riesling history To this day, the oldest Schloss Johannisberger Riesling – a 1748 vintage – still lies in the Bibliotheca Subterranea, the 900-year-old cellarium and the estate’s treasure trove. Alongside are numerous precious Riesling wines created by the estate’s cellarmasters over the past 300 years. -

Corn Syrup, Grape Syrup, Honey, (A Shengreen , 1975

LABORATORY COMPARISON OF HIGH FRUCTOSE CORN SYRUP, GRAPE SYRUP, HONEY, AND SUCROSE SYRUP AS MAINTENANCE FOOD FOR CAGED HONEY BEES Roy J. BARKER Yolanda LEHNER U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Bee Research Laboratory, 2000 East Allen Road, Tucson, Arizona 85719 SUMMARY Honey or high fructose corn syrup fed to worker bees failed to show any advantage over sucrose syrup. Grape syrup caused dysentery and reduced survival. Caged bees survived longest on sucrose syrup. INTRODUCTION A commercial process utilizes glucose isomerase to convert the glucose from hydrolyzed corn starch to a mixture containing glucose and high levels of fructose (ASHENGREEN, 1975). To humans, fructose is sweeter than glucose or sucrose. Consequently, the higher the content of fructose, the lower the concentration of sugar needed to sweeten food or drinks. Thus, high fructose corn syrup is an economical sweetener for humans. Does isomerized corn syrup provide advantages in bee foods? Its sugar composition closely resembles that of honey, but isomerized sugar may not be sweeter than sucrose to honey bees. In fact, a preference of older bees for sucrose over glucose and fructose may explain why they leave hives containing stored honey to forage for nectar. Nevertheless, beekeepers generally consider honey to be unparalleled as a bee food despite its failure to sustain worker bees as long as sucrose (BARKER and LEHNER, 1974 a, b). High fructose corn syrup offers advantages besides lower cost, such as feeding convenience. Furthermore, some beekeepers find less robbing when bees are fed high fructose corn syrup instead of sucrose syrup. This may be a consequence of lower attraction. -

Kulturhistorische Sehenswürdigkeiten Cultur Al & Historic Sights Wiesbaden - Rheingau

LANDESHAUPTSTADT Deutsch | English KULTURHISTORISCHE SEHENSWÜRDIGKEITEN CULTUR AL & HISTORIC SIGHTS Wiesbaden - Rheingau www.wiesbaden.de Wiesbaden Kulturhistorische Sehenswürdigkeiten Rheingau Cultural & Historic Sights Hardly any other region in Germany offers the possibilities of a lively city In kaum einer anderen Region Deutschlands sind die Wege zwischen den and the pleasantries of an attractive tourist region in such short distance as Möglichkeiten einer lebendigen Stadt und den Annehmlichkeiten einer Wiesbaden and the Rheingau. Together they form a unique destination with touristisch attraktiven Region so kurz wie zwischen Wiesbaden und dem an unmistakable wealth of culture and nature. Rheingau. Gemeinsam bilden sie eine einzigartige Destination mit einem unverwechselbaren Reichtum an Kultur und Natur. Alongside churches built in the most varied styles of architecture, magnificent places as well as an electoral castle and monasteries characterized by centu- Neben Kirchen unterschiedlichster Baukunst, prächtigen Schlössern sowie ries einer kurfürstlichen Burg laden von jahrhundertealter Weinbautradition of old winegrowing tradition invite us to go on an excursion into the past. geprägte Klöster zu einem Ausflug in die Vergangenheit ein. Furthermore the region offers two UNESCO World Heritages to be discovered: Darüber hinaus sind in der Region gleich zwei UNESCO-Welterben zu besichtigen: the Upper Germanic and Raetian Limes along a stretch of 42 km as well as the Teile des Obergermanisch-raetischen Limes auf insgesamt 42 km sowie der World Heritage Upper Middle Rhine Valley starting at Rüdesheim am Rhein and Beginn des Welterbes Oberes Mittelrheintal bei Rüdesheim am Rhein und Lorch am Rhein. Lorch am Rhein. This brochure is intended to give you an overview of selected cultural and Diese Broschüre möchte Ihnen einen Überblick über ausgewählte kultur- historic buildings in the region of Wiesbaden-Rheingau as well as giving you historische Bauwerke in der Region Wiesbaden-Rheingau geben und bietet the opportunity to explore a section of the Taunus. -

Elite Golds 2017

Canberra International Riesling Challenge October 2017 ELITE GOLDS Excluding Trophy winners. Elite Gold is equal to or better than 96 points. Class Winery Wine Vintage Region Country 1 Alkoomi Wines 2017 Alkoomi White Label Riesling 2017 Great Southern Australia 1 Coal Valley Vineyard Coal Valley Vineyard Riesling 2017 Tasmania Australia 1 Pioneer Road Pioneer Road Riesling 2017 Clare Valley Australia 1 Thorn-Clarke Wines Sandpiper Riesling 2017 Eden Valley Australia 4 Australian Vintage Ltd McGuigan Shortlist Riesling 2015 2015 Eden Valley Australia 4 Gilbert Family Wines Gilbert + Gilbert 2015 Single Vineyard Riesling 2015 Eden Valley Australia 4 Heggies Vineyard Heggies Vineyard Estate Riesling 2016 Eden Valley Australia 4 Jaeschkes Hill River Clare Jaeschkes Hill River Clare Estate 2015 Clare Valley Australia Estate 4 Kilikanoon Wines Mort's Block Riesling 2016 Clare Valley Australia 4 Laurel Bank Wines Laurel Bank Riesling 2016 Tasmania Australia 4 Willoughby Park Willoughby Park Kalgan River Riesling 2016 2016 Great Southern Australia 7 Bird in Hand Bird in Hand Riesling 2010 Clare Valley Australia 7 Forbes Wine Company Cellar Matured Eden Valley Riesling 2009 Eden Valley Australia 7 Jacob's Creek Wines Jacob's Creek Steingarten Riesling 2012 Barossa Australia 7 Jaeschkes Hill River Clare Jaeschkes Hill River Clare Estate 2013 Clare Valley Australia Estate 7 Koonowla Wines Koonowla Riesling 2006 Clare Valley Australia 7 Paulett Wines Aged Release Riesling 2011 Clare Valley Australia 7 Robert Stein Winery Robert Stein Premium Riesling -

Cocktail Chemistry View Menu

Introduction We wanted to do a menu that looked at some of the stranger parts of mixing drinks. Here is collection of 16 cocktails that each have an element of weird science to them. We look at infusions of flavour, manipulations of texture and emulsions, the balance of sugar and acidity, density and carbonation, amongst others. Our top priority was for these drinks to taste good and be enjoyed. There is a lot of information about the processes behind the drinks as well for anyone interested. For this course you will need: Hibiscus infused Bathtub Punch Mezcal Fizz £9 Nitrogen pressured infusion £32 Natural maceration infusion Hibiscus infused Del Maguey Mezcal Vida, DOM Benedictine, Yellow Chartreuse, Lemon Juice, Bathtub Gin, Briottet Kumquat Liqueur, London Fields Hackney Hopster Pale Ale, Soda Water, Hibiscus Syrup, Egg White, Soda Water Butterfly Pea Syrup, Citric Acid Slight smokiness, floral vibes, fresh citrus burst Light, fresh, easy drinking orange and citrus forward; three-litre sharing vessel Alcohol’s ability to suck flavours from herbs, You can infuse flavours into alcohol almost instantly with nothing more than an iSi Cream fruits and spices by infusion and then Osmosis and Dissolution Whipper. An iSi whipper is a siphon chefs have used for years that uses nitrogen to create preserve those flavours has been used since There are two processes which occur when whipped cream and more creatively, foams. They received a notable bump in popularity in the middle ages, originally by monks to you’re infusing certain ingredients in alcohol: the 90s when chef Ferran Adrià used them heavily in his ground-breaking restaurant El Bulli produce medicinal potions. -

Barker Recipe List

Sweet Stuff: Karen Barker’s American Desserts karen barker, university of north carolina press, 2004 Complete Recipe List The Basics: A Pie Primer A Baker's Building Blocks Blueberry Blackberry Pie Basic Pie Crust Apple Rhubarb Cardamom Crumb Pie Basic Tart Dough Meyer Lemon Shaker Pie My Favorite Dough for Individual Tarts Buttermilk Vanilla Bean Custard Pie Flaky Puff-Style Pastry Maple Bourbon Sweet Potato Pie Cream Cheese Pastry Mocha Molasses Shoofly Pie Cinnamon Graham Pastry Key Lime Coconut Pie with Rum Cream Newton Tart Dough Chocolate Raspberry Fudge Pie Walnut Pastry Dough Lemon Pecan Tart Fig Newton Zinfandel Tart The Caramelization Chronicles Banana and Peanut Frangipane Tarts Browned Butter Date Nut Tart Caramel Sauce Chocolate Chip Cookie Tarts Cocoa Fudge Sauce Chocolate Chestnut Tarts Chocolate Pudding Sauce Chocolate Grand Marnier Truffle Tart Creamy Peanut Butter and Honey Sauce Cranberry Linzer Tart Hot Buttered Rum Raisin Sauce Lime Meringue Tart Gingered Maple Walnut Sauce Rustic Raspberry Tart Lynchburg Lemonade Sauce Pink Grapefruit Soufflé Tarts Cinnamon Spiced Blueberry Sauce Cherry Vanilla Turnovers Pineapple Caramel—and Variations on the Theme Rhubarb Cream Cheese Dumplings A Couple of Apple Sauces Raspberry Red Wine Sauce Fruit Somethings Strawberry Crush Concord Grape Syrup Bourbon Peach Cobbler with Cornmeal Cream Biscuits Mint Syrup Deep-Dish Brown Sugar Plum Cobbler Coffee Syrup Spiced Apple Cobbler with Cheddar Cheese Chocolate Ganache Biscuit Topping Homemade Chocolate Chips Blueberry Buckle with Coconut -

DIVISION III HOME ECONOMICS AWARDS and JUDGING: First, Second and Third Place Ribbons Will Be Awarded in All Categories

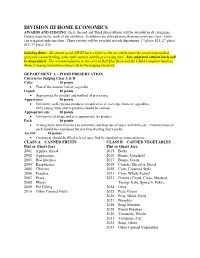

DIVISION III HOME ECONOMICS AWARDS AND JUDGING: First, Second and Third place ribbons will be awarded in all categories. Entries must be the work of the exhibitor. Exhibitors are allowed more than one entry per class. Entry can win prize only one time. Three rosettes will be awarded in each department: 1st place: $25, 2nd place: $15, 3rd place: $10. Labeling Rules: All canned goods MUST have a label on the jar which states the processing method (pressure canner/boiling water bath canner) and the processing time. Jars submitted without labels will be disqualified. The recommendations in the current Ball Blue Book and the USDA Complete Guide to Home Canning (available online) will be the judging standard. DEPARTMENT A – FOOD PRESERVATION Criteria for Judging Class A & B Color 20 points That of the natural fruit or vegetable Liquid 10 points Appropriate for product and method of processing Appearance 40 points Uniformly well-ripened products; no defective or over-ripe fruits or vegetables. Only young fruits and vegetables should be canned. Appropriate size 10 points Uniformity of shape and size appropriate for product. Pack 10 points Arrangement with reference to symmetry and best use of space within the jar. Attractiveness of pack should be considered but not time-wasting fancy packs. Jar Fill 10 points Containers should be filled to level specified by standard recommendations. CLASS A – CANNED FRUITS CLASS B – CANNED VEGETABLES Pint or Quart Jars Pint or Quart Jars 2001 Apples, sliced 2015 Beets 2002 Applesauce 2016 Beans, Cornfield -

Thesis-1980-E93l.Pdf

LAMBAESIS TO THE REIGN OF HADRIAN By DIANE MARIE HOPPER EVERMAN " Bachelor of Arts Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma December, 1977 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS July 25, 1980 -n , ,111e.5J s LAMBAESIS TO THE REIGN OF HADRIAN Thesis Approved: Dean of the Graduate College ii 10S2909 PREFACE Lambaesis was a Roman Imperial military fortress in North Africa in the modern-day nation of Algeria. Rome originally acquired the territory as a result of the defeat of Carthage in the Punic Wars. Expansion of territory and settlement of surplus population were two ideas behind its Romanization. However, North Africa's greatest asset for becoming a province was its large yield of grain. This province furnished most of the wheat for the empire. If something happened to hinder its annual production level then Rome and its provinces would face famine. Unlike most instances of acquiring territory Rome did not try to assimilate the native transhumant population. Instead these inhabitants held on to their ancestral lands until they were forcibly removed. This territory was the most agriculturally productive; unfortunately, it was also the area of seasonal migration for the native people. Lambaesis is important in this scheme because it was the base of the solitary legion in North Africa, the III Legio Augusta. After beginning in the eastern section of the province just north of the Aures Mountains the legion gradually moved west leaving a peaceful area behind. The site of Lambaesis was the III Legio Augusta's westernmost fortress.