The Vintner's Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appetizers Our Homemade Bread

our homemade bread WITH WHITE FLOUR BREAD (BIO) €1,50/PERSON MULTIGRAIN CAROB (BIO) €1,50/PERSON appetizers KATAIFI CHEESE BALLS NEW €7,50 WITH KOPANISTI MYKONOU (SALTY & SPICY CHEESE), HONEY AND NIGELLA SEEDS ZUCCHINI BALLS €7,50 WITH YOGHURT MOUSSE TRIPLE-FRIED NAXOS POTATOES • WITH OREGANO AND THYME €5,50 • WITH EGGS OVER EASY, FETA CHEESE CREAM AND €8,50 SINGLINO FROM MANI (SMOKED SALTED PORK) OVEN BAKED VEAL MEATBALLS NEW €9,00 WITH TOMATO MARMALADE PASTRAMI ROLLS NEW €7,50 PASTRAMI FROM DRAMA IN A BAKED ROLL WITH TOMATO SAUCE AND KASSERI (TRADITIONAL CHEESE) FROM XANTHI OUR DELICACIES PLATTER €12,50 SALAMI FROM LEFKADA, PROSCIUTTO FROM DRAMA, SINGLINO FROM MANI, KOPANISTI FROM MYKONOS, KASSERI FROM XANTHI, ARSENIKO FROM NAXOS, DRIED FRUITS AND CHERRY TOMATOES SPETZOFAI NEW €9,50 WITH SPICY SAUSAGE FROM DRAMA AND GRILLED FLORINA PEPPERS SXINOUSA'S FAVA NEW €12,50 SPLIT PEAS WIITH CAPER SALAD, SUN DRIED TOMATOES, OLIVES AND CHERRY TOMATOES MARINATED HORNBEAM TART NEW €11,00 WITH GREEN SALAD, SUN DRIED TOMATOES AND TARAMA (FISH ROE) SALAD CREAM BREADED EGGS NEW €7,00 WITH CRUNCHY CRUST AND SAUT�ED GREENS www.kiouzin.com REGULAR salads ONE PERSON WILD FOREST MUSHROOMS WITH PLEUROTUS €10,50 €7,50 MEDITERRANEAN SPAGHETTI NEW €8,50 MUSHROOMS, CREAM CHEESE TRUFFLES AND FRESH WITH FRESH TOMATO, ONION, OLIVES AND CAPERS GOJI BERRIES, GREEN AND RED LOLA, BABY SPINACH AND BABY ROCA, PARSLEY, MULTICOLOR PEPPERS,CHERRY SPAGHETTI WITH MESOLONGI FISH ROE, €16,50 TOMATOES AND A VINAIGRETTE PETIMEZI (GRAPE SYRUP) WITH BASIL AND CHERRY TOMATOES SUPERFOODS -

Corn Syrup, Grape Syrup, Honey, (A Shengreen , 1975

LABORATORY COMPARISON OF HIGH FRUCTOSE CORN SYRUP, GRAPE SYRUP, HONEY, AND SUCROSE SYRUP AS MAINTENANCE FOOD FOR CAGED HONEY BEES Roy J. BARKER Yolanda LEHNER U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Bee Research Laboratory, 2000 East Allen Road, Tucson, Arizona 85719 SUMMARY Honey or high fructose corn syrup fed to worker bees failed to show any advantage over sucrose syrup. Grape syrup caused dysentery and reduced survival. Caged bees survived longest on sucrose syrup. INTRODUCTION A commercial process utilizes glucose isomerase to convert the glucose from hydrolyzed corn starch to a mixture containing glucose and high levels of fructose (ASHENGREEN, 1975). To humans, fructose is sweeter than glucose or sucrose. Consequently, the higher the content of fructose, the lower the concentration of sugar needed to sweeten food or drinks. Thus, high fructose corn syrup is an economical sweetener for humans. Does isomerized corn syrup provide advantages in bee foods? Its sugar composition closely resembles that of honey, but isomerized sugar may not be sweeter than sucrose to honey bees. In fact, a preference of older bees for sucrose over glucose and fructose may explain why they leave hives containing stored honey to forage for nectar. Nevertheless, beekeepers generally consider honey to be unparalleled as a bee food despite its failure to sustain worker bees as long as sucrose (BARKER and LEHNER, 1974 a, b). High fructose corn syrup offers advantages besides lower cost, such as feeding convenience. Furthermore, some beekeepers find less robbing when bees are fed high fructose corn syrup instead of sucrose syrup. This may be a consequence of lower attraction. -

Cocktail Chemistry View Menu

Introduction We wanted to do a menu that looked at some of the stranger parts of mixing drinks. Here is collection of 16 cocktails that each have an element of weird science to them. We look at infusions of flavour, manipulations of texture and emulsions, the balance of sugar and acidity, density and carbonation, amongst others. Our top priority was for these drinks to taste good and be enjoyed. There is a lot of information about the processes behind the drinks as well for anyone interested. For this course you will need: Hibiscus infused Bathtub Punch Mezcal Fizz £9 Nitrogen pressured infusion £32 Natural maceration infusion Hibiscus infused Del Maguey Mezcal Vida, DOM Benedictine, Yellow Chartreuse, Lemon Juice, Bathtub Gin, Briottet Kumquat Liqueur, London Fields Hackney Hopster Pale Ale, Soda Water, Hibiscus Syrup, Egg White, Soda Water Butterfly Pea Syrup, Citric Acid Slight smokiness, floral vibes, fresh citrus burst Light, fresh, easy drinking orange and citrus forward; three-litre sharing vessel Alcohol’s ability to suck flavours from herbs, You can infuse flavours into alcohol almost instantly with nothing more than an iSi Cream fruits and spices by infusion and then Osmosis and Dissolution Whipper. An iSi whipper is a siphon chefs have used for years that uses nitrogen to create preserve those flavours has been used since There are two processes which occur when whipped cream and more creatively, foams. They received a notable bump in popularity in the middle ages, originally by monks to you’re infusing certain ingredients in alcohol: the 90s when chef Ferran Adrià used them heavily in his ground-breaking restaurant El Bulli produce medicinal potions. -

Barker Recipe List

Sweet Stuff: Karen Barker’s American Desserts karen barker, university of north carolina press, 2004 Complete Recipe List The Basics: A Pie Primer A Baker's Building Blocks Blueberry Blackberry Pie Basic Pie Crust Apple Rhubarb Cardamom Crumb Pie Basic Tart Dough Meyer Lemon Shaker Pie My Favorite Dough for Individual Tarts Buttermilk Vanilla Bean Custard Pie Flaky Puff-Style Pastry Maple Bourbon Sweet Potato Pie Cream Cheese Pastry Mocha Molasses Shoofly Pie Cinnamon Graham Pastry Key Lime Coconut Pie with Rum Cream Newton Tart Dough Chocolate Raspberry Fudge Pie Walnut Pastry Dough Lemon Pecan Tart Fig Newton Zinfandel Tart The Caramelization Chronicles Banana and Peanut Frangipane Tarts Browned Butter Date Nut Tart Caramel Sauce Chocolate Chip Cookie Tarts Cocoa Fudge Sauce Chocolate Chestnut Tarts Chocolate Pudding Sauce Chocolate Grand Marnier Truffle Tart Creamy Peanut Butter and Honey Sauce Cranberry Linzer Tart Hot Buttered Rum Raisin Sauce Lime Meringue Tart Gingered Maple Walnut Sauce Rustic Raspberry Tart Lynchburg Lemonade Sauce Pink Grapefruit Soufflé Tarts Cinnamon Spiced Blueberry Sauce Cherry Vanilla Turnovers Pineapple Caramel—and Variations on the Theme Rhubarb Cream Cheese Dumplings A Couple of Apple Sauces Raspberry Red Wine Sauce Fruit Somethings Strawberry Crush Concord Grape Syrup Bourbon Peach Cobbler with Cornmeal Cream Biscuits Mint Syrup Deep-Dish Brown Sugar Plum Cobbler Coffee Syrup Spiced Apple Cobbler with Cheddar Cheese Chocolate Ganache Biscuit Topping Homemade Chocolate Chips Blueberry Buckle with Coconut -

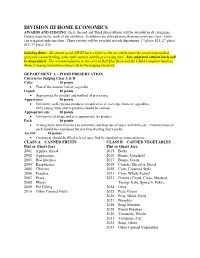

DIVISION III HOME ECONOMICS AWARDS and JUDGING: First, Second and Third Place Ribbons Will Be Awarded in All Categories

DIVISION III HOME ECONOMICS AWARDS AND JUDGING: First, Second and Third place ribbons will be awarded in all categories. Entries must be the work of the exhibitor. Exhibitors are allowed more than one entry per class. Entry can win prize only one time. Three rosettes will be awarded in each department: 1st place: $25, 2nd place: $15, 3rd place: $10. Labeling Rules: All canned goods MUST have a label on the jar which states the processing method (pressure canner/boiling water bath canner) and the processing time. Jars submitted without labels will be disqualified. The recommendations in the current Ball Blue Book and the USDA Complete Guide to Home Canning (available online) will be the judging standard. DEPARTMENT A – FOOD PRESERVATION Criteria for Judging Class A & B Color 20 points That of the natural fruit or vegetable Liquid 10 points Appropriate for product and method of processing Appearance 40 points Uniformly well-ripened products; no defective or over-ripe fruits or vegetables. Only young fruits and vegetables should be canned. Appropriate size 10 points Uniformity of shape and size appropriate for product. Pack 10 points Arrangement with reference to symmetry and best use of space within the jar. Attractiveness of pack should be considered but not time-wasting fancy packs. Jar Fill 10 points Containers should be filled to level specified by standard recommendations. CLASS A – CANNED FRUITS CLASS B – CANNED VEGETABLES Pint or Quart Jars Pint or Quart Jars 2001 Apples, sliced 2015 Beets 2002 Applesauce 2016 Beans, Cornfield -

Tutored Wine Tasting Thursday 13Th July 2017

Tutored Wine Tasting Thursday 13th July 2017 SWEET WINES “The various ways winemakers can achieve sweetness in their wines” Speaker: Eric LAGRE Head Sommelier SWEET WINE TASTING Speaker: Eric LAGRE, EIC Head Sommelier Thursday 13th July 2017 Tasting notes by Eric LAGRE and Magda KOTLARCZYK, WSET Diploma graduates (with the participation of Nora ESPINOSA CORONEL, WSET Diploma student) (1) 2016, Vin Cuit Selon la Vieille Tradition Provençale, Domaine les Bastides (Carole Salen) Produced in Puy-Sainte-Réparade near Aix-en-Provence, Provence, France (2) 2014, Ben Ryé, Passito di Pantelleria DOC, Donnafugata (Stefano Valla) Produced on the island of Pantelleria then bottled in Sicily, Italy (3) NV, Pineau des Charentes AC, Domaine Gardrat (Lionel Gardrat) Produced in Cozes near Roan in the Cognac-producing region of the Charentes, France (4) 2016, Moscato d’Asti di Strevi DOCG, Contero (Patrizia Marenco) Produced in Strevi, in the Asti-producing region of Piedmont, Italy (5) NV, Champagne Veuve Clicquot Rich, LVMH Group (Dominique Demarville) Produced in Reims from grapes grown in the Champagne-producing region, France (6) 2010, Grünlack Riesling Spätlese, Schloss Johannisberg (Hans Kessler) Produced in the Rheingau, Germany (7) 2014, Grand Constance, Groot Constantia (Boela gerber) Produced in the winegrowing region of Constantia, Western Cape, South Africa (8) 2014, Gold Vidal Icewine, Inniskillin (Bruce Nicholson) Produced in the Niagara Peninsula, Ontario, Canada (9) 2007, Tokaji Aszú 6 Puttonyos, Dobogó (Attila Domokos) Produced in Tokaj from grapes grown in the sub-regions of Mád and Tállya, North-eastern Hungary (10) NV, Grand Rutherglen Topaque (Andrew Drumm) Produced in Rutherglen, North-eastern Victoria, Australia HOW DO WINEMAKERS ACHIEVE SWEETNESS IN THEIR WINES? * The history of the wine trade in the Ancient World could easily be summed up into a history of sweet wines, for only wine with a high alcohol and sugar content was stable enough to travel in those days. -

Assessment on Nutrition Related to Anemia in Ferghana Oblast

ENSURING ACCESS TO QUALITY HEALTH CARE IN CENTRAL ASIA TRIP REPORT: Assessment on Nutrition Related to Anemia in Ferghana Oblast Author: Dr Gaukhar Abuova February 21 – March 7, 2001 Ferghana Oblast, Uzbekistan FUNDED BY: THE U.S. AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT IMPLEMENTED BY: ABT ASSOCIATES INC. CONTRACT NO. 115-C-00-00-00011-00 TRIP REPORT: Assessment on Nutrition Related to Anemia in Ferghana Oblast Author: Dr Gaukhar Abuova February 21 – March 7, 2001 Ferghana Oblast, Uzbekistan 22222222222Title Table of Contents I. Abstract .......................................................................................................................................................................1 II. Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................................2 III. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................3 A. Specifics of the Diet of Rural Women in the Ferghana Oblast...................................................................3 B. Typical Diet of the Rural Populace in the Ferghana Oblast (Women).......................................................4 C. Recommendations...............................................................................................................................................7 Annex 1: Work Schedule..............................................................................................................................................9 -

Crushed Fruits and Syrups William Fenton Robertson University of Massachusetts Amherst

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1936 Crushed fruits and syrups William Fenton Robertson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Robertson, William Fenton, "Crushed fruits and syrups" (1936). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1914. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1914 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MASSACHUSETTS STATE COLLEGE Us LIBRARY PHYS F SCI LD 3234 M268 1936 R652 CRUSHED FRUITS AND SYRUPS William Fenton Robertson Thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Science Massachusetts State College, Amherst June 1, 1936 8 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION Page 1 II. GENERAL DISCUSSION OF PRODUCTS, TYPES AND TERMS AS USED IN THE TRADE 2 Pure Product Pure Flavored Products Imitation Products Types of Products Terms used in fountain supply trade and their explanation III. DISCUSSION OF MATERIALS AND SOURCE OF SUPPLY 9 Fruits Syrups and Juices Colors Flavors Other Ingredients IV. MANUFACTURING PROCEDURE AND GENERAL AND SPECIFIC FORMULAE 15 Fruits - General Formula Syrups - General Formula Flavored Syrups - General Formula Specific Formulae Banana Extract, Imitation Banana Syrup, Imitation Birch Beer Extract, Imitation Birch Beer Syrup, Imitation Cherry Syrup, Imitation Chocolate Flavored Syrup Chooolate Flavored Syrup, Double Strength Coffee Syrup Ginger Syrup Grape Syrup Lemon Syrup, No. I Lemon Syrup, No. II Lemon and Lime Syrup Orange Syrup Orangeade cx> Pineapple Syrup Raspberry Syrup ~~~ Root Beer Syrup ^ Strawberry Syrup ui TABLE OF CONTENTS (Continued) Vanilla Syrup Butterscotch Caramel Fudge Cherries Frozen Pudding Chocolate Fudge Ginger Glace Marshmallow Crushed Raspberries Walnuts in Syrup Pectin Emulsion CRUSHED FRUIT V. -

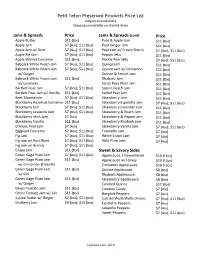

Petit Teton Preserved Products Price List Subject to Availability Shipping Unavailable on Starred Items

Petit Teton Preserved Products Price List Subject to availability Shipping unavailable on starred items Jams & Spreads Price Jams & Spreads (cont) Price Apple Butter $11 (8oz) Pear & Apple Jam $11 (8oz) Apple Jam $7 (4oz); $11 (8oz) Pear Ginger Jam $11 (8oz) Apple Jam w/ Rum $7 (4oz); $11 (8oz) Pear Jam w/ Cream Sherry $7 (4oz); $11 (8oz) Apple Pie Jam $7 (4oz); $11 (8oz) Pepper Jelly $11 (8oz) Apple Walnut Conserve $11 (8oz) Prickly Pear Jelly $7 (4oz); $11 (8oz) Babcock White Peach Jam $7 (4oz); $11 (8oz) Quince Jam $11 (8oz) Babcock White Peach Jam $7 (4oz); $11 (8oz) Quince Jam w/ Cinnamon $11 (8oz) w/ Ginger Quince & Fennel Jam $11 (8oz) Babcock White Peach Jam $11 (8oz) Rhubarb Jam $11 (8oz) w/ Lavender Santa Rosa Plum Jam $11 (8oz) Bartlett Pear Jam $7 (4oz); $11 (8oz) Saturn Peach Jam $11 (8oz) Bartlett Pear Jam w/ Vanilla $11 (8oz) Seckel Pear Jam $11 (8oz) Beet Marmalade $7 (4oz); $11 (8oz) Strawberry Jam $11 (8oz) Blackberry Hazelnut Conserve $11 (8oz) Strawberry Espelette Jam $7 (4oz); $11 (8oz) Blackberry Jam $7 (4oz); $11 (8oz) Strawberry Lavender Jam $11 (8oz) Blackberry Jalapeno Jam $7 (4oz); $11 (8oz) Strawberry & Peach Jam $11 (8oz) Blackberry Mint Jam $7 (4oz) Strawberry & Pepper Jam $11 (8oz) Blackberry Vanilla $11 (8oz) Strawberry Rhubarb Jam $11 (8oz) D’Anjou Pear Jam $7 (4oz) Strawberry Vanilla Jam $7 (4oz); $11 (8oz) Eggplant Conserve $7 (4oz); $11 (8oz) Tomatillo Jam $7 (4oz) Fig Jam $7 (4oz); $11 (8oz) White Grape Jam $7 (4oz) Fig Jam w/ Port Wine $7 (4oz); $11 (8oz) Wild Plum Jam $7 (4oz) Fig Jam w/ Brandy $7 -

Fruit Syrups & Honeys

https://hgic.clemson.edu/ FRUIT SYRUPS & HONEYS Factsheet | HGIC 3165 | Updated: Jun 29, 2001 Fruit Syrups Juices from fresh or frozen blueberries, cherries, grapes, raspberries (black or red) and strawberries are easily made into toppings for use on ice cream, pancakes and pastries. Fruit syrups are made by cooking fruit juice or pulp with sugar to the consistency of syrup. Berry Syrup Ingredients: 1¼ cups prepared blackberry, blueberry, raspberry or strawberry juice 1½ cups sugar ¼ cup corn syrup 1 tablespoon bottled lemon juice Yield: About 2 half-pint jars To Prepare Juice: Select table-ripe berries. Do not use underripe berries. Wash, cap and remove stems. Crush berries and heat to a boil. Simmer 1 or 2 minutes until soft, stirring to prevent scorching. Do not overcook; excess boiling will destroy the pectin, flavor and color. Note: Juicy berries may be crushed and the juice extracted without heating. To Extract Juice: Pour everything into a damp jelly bag or four layers of cheesecloth, and suspend the bag to drain the juice. The clearest jelly or syrup comes from juice that has dripped through a jelly bag without pressing or squeezing. To Make Syrup: Sterilize canning jars. Combine ingredients in a saucepan. Bring to a rolling boil and boil one minute. Remove from heat and skim off foam. Pour into hot half-pint jars, leaving ¼-inch headspace. Wipe jar rims and adjust lids. Process 10 minutes in a boiling water bath. Grape Syrup Ingredients: 1¼ cups grape purée 1½ cups sugar ¼ cup corn syrup 1 tablespoon bottled lemon juice Yield: About 2 half-pint jars To Prepare Purée: Wash and stem ripe grapes. -

To Start Salads Wood Fired Pizza Handcrafted Pasta

WEDNESDAY, APRIL 8th 2020 TO START HANDCRAFTED PASTA made in house daily PANE BIANCO (Grilled Bread) 5 SWEET PEA AGNOLOTTI 22 garlic, extra virgin olive oil, sea salt butter, garlic, mushrooms MARINATED OLIVES 6 BUCATINI 22 castelveltrano, nicoise, picholine spicy tomato sauce, pancetta, red onion, pecorino ARANCINI 10 MEZZI RIGATONI 22 sausage ragu crispy risotto balls with mozzarella, basil pesto, tomato sauce TAGLIATELLE 23 ribbon noodles, lamb ragu BURRATA WITH FAVA BEANS 15 FUSILLI 22 english peas, smoked prosciutto, herbs, toast roasted chicken, pancetta, mushrooms, marsala, herbs BRAISED MEATBALLS 15 TAGLIOLINI 26 thin ribbon noodles, spicy tomato sauce, shrimp, crab, arugula tomato sauce, grilled bread SPAGHETTI WITH MEATBALLS 24 TRUFFLE FRIES 10 tomato sauce, parmigiano aioli, parmigiano LASAGNA 25 traditional bolognese sauce, basil SALADS ARUGULA 8 / 14 PLATES radicchio, shaved parmigiano, lemon vinaigrette BRAISED BEEF SHORT RIB 32 BUTTER LETTUCES 10 / 18 polenta, horseradish bacon, avocado, gorgonzola vinaigrette, walnuts, onions WOOD BURNING HEARTH KALE 9 / 16 pecorino, almonds, caesar Choice of one side or substitute any salad for an additional $2 ITALIAN CHOPPED 10 / 18 MARY’S FREE RANGE HALF CHICKEN 28 salsa verde iceberg, radicchio, salami, provolone, tomato, pepperoncini, oregano vinaigrette SALMON 28 lemon, arugula SLICED HANGER STEAK, 8 OZ 30 WOOD FIRED PIZZA aged balsamic MARGHERITA 14 BRANDT FARMS NEW YORK STRIP, 10 OZ 32 tuscan rub tomato sauce, mozzarella, basil RIBEYE, 14 OZ 41 PEPPERONI 16 porcini rub tomato -

Middle Eastern Cuisine

MIDDLE EASTERN CUISINE The term Middle Eastern cuisine refers to the various cuisines of the Middle East. Despite their similarities, there are considerable differences in climate and culture, so that the term is not particularly useful. Commonly used ingredients include pitas, honey, sesame seeds, sumac, chickpeas, mint and parsley. The Middle Eastern cuisines include: Arab cuisine Armenian cuisine Cuisine of Azerbaijan Assyrian cuisine Cypriot cuisine Egyptian cuisine Israeli cuisine Iraqi cuisine Iranian (Persian) cuisine Lebanese cuisine Palestinian cuisine Somali cuisine Syrian cuisine Turkish cuisine Yemeni cuisine ARAB CUISINE Arab cuisine is defined as the various regional cuisines spanning the Arab World from Iraq to Morocco to Somalia to Yemen, and incorporating Levantine, Egyptian and others. It has also been influenced to a degree by the cuisines of Turkey, Pakistan, Iran, India, the Berbers and other cultures of the peoples of the region before the cultural Arabization brought by genealogical Arabians during the Arabian Muslim conquests. HISTORY Originally, the Arabs of the Arabian Peninsula relied heavily on a diet of dates, wheat, barley, rice and meat, with little variety, with a heavy emphasis on yogurt products, such as labneh (yoghurt without butterfat). As the indigenous Semitic people of the peninsula wandered, so did their tastes and favored ingredients. There is a strong emphasis on the following items in Arabian cuisine: 1. Meat: lamb and chicken are the most used, beef and camel are also used to a lesser degree, other poultry is used in some regions, and, in coastal areas, fish. Pork is not commonly eaten--for Muslim Arabs, it is both a cultural taboo as well as being prohibited under Islamic law; many Christian Arabs also avoid pork as they have never acquired a taste for it.