Gender Within Specialist Police Departments at an Operational Level

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Day 72 Grenfell Tower Public Inquiry 13 November 2018 (+44)207

Day 72 Grenfell Tower Public Inquiry 13 November 2018 1 Tuesday, 13 November 2018 1 an incident, and at that point I was neither in 2 (10.00 am) 2 a position to have good communications, neither had 3 SIR MARTIN MOORE-BICK: Good morning, everyone. Welcome to 3 I been properly briefed as I would be at 04.10 when 4 today's hearing. 4 I came in. And also my location in a vehicle on 5 We are going to begin by hearing the rest of 5 a motorway was difficult as well. 6 Commander Jerome's evidence. 6 Q. You say in paragraph 46: 7 MR MILLETT: Good morning, Mr Chairman. Yes, we are. 7 "He briefed me on the nature of the incident, the 8 Can I please call Commander Jerome back. 8 command structure put in place, the resources being 9 NEIL JEROME (continued) 9 deployed, and the current status of the activations 10 Questions by COUNSEL TO THE INQUIRY (continued) 10 initiated on my earlier call." 11 MR MILLETT: Commander, good morning. 11 During that briefing, did he give you any further 12 A. Good morning. 12 new information about the incident? 13 Q. Thank you very much for coming back to us this morning. 13 A. Would it be okay to refer to my notes? 14 A. Thank you. 14 Q. Yes, of course. 15 Q. I am going to turn now to your involvement on the night, 15 A. Thank you. 16 or, rather, to turn back to it. 16 Q. Just so we know what those are, I think you're referring 17 Can I ask you, please, to go to page 13 of your 17 to the Jerome log, which is at MET00023289. -

Agenda Document for Sussex Police and Crime Panel, 05/10/2018 10:30

Public Document Pack Sussex Police and Crime Panel Members are hereby requested to attend the meeting of the Sussex Police and Crime Panel, to be held at 10.30 am on Friday, 5 October 2018 at County Hall, Lewes. Tony Kershaw Clerk to the Police and Crime Panel 27 September 2018 Webcasting Notice Please note: This meeting will be filmed for live or subsequent broadcast via East Sussex County Council’s website on the internet – at the start of the meeting the Chairman will confirm that the meeting is to be filmed. Generally the public gallery is not filmed. However, by entering the meeting room and using the public seating area you are consenting to being filmed and to the possible use of those images and sound recordings for webcasting and/or training purposes. The webcast will be available via the link below: http://www.eastsussex.public-i.tv/core/. Agenda 10.30 am 1. Declarations of Interest Members and officers must declare any pecuniary or personal interest in any business on the agenda. They should also make declarations at any stage such an interest becomes apparent during the meeting. Consideration should be given to leaving the meeting if the nature of the interest warrants it. If in doubt contact Democratic Services, West Sussex County Council, before the meeting. 10.35 am 2. Minutes (Pages 5 - 16) To confirm the minutes of the previous meeting on 29 June (cream paper). 10.40 am 3. Urgent Matters Items not on the agenda which the Chairman of the meeting is of the opinion should be considered as a matter of urgency. -

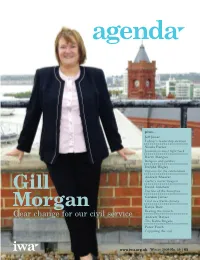

Gill Morgan, Is Dealing with Whitehall Arrogance

plus… Jeff Jones Labour’s leadership election Nicola Porter Journalism must fight back Barry Morgan Religion and politics Dafydd Wigley Options for the referendum Andrew Shearer Garlic’s secret weapon Gill David Culshaw Decline of the honeybee Gordon James Coal in a warm climate Morgan Katija Dew Beating the crunch Gear change for our civil service Andrew Davies The Kafka Brigade Peter Finch Capturing the soul www.iwa.org.uk Winter 2009 No. 39 | £5 clickonwales ! Coming soon, our new website www. iwa.or g.u k, containing much more up-to-date news and information and with a freshly designed new look. Featuring clickonwales – the IWA’s new online service providing news and analysis about current affairs as it affects our small country. Expert contributors from across the political spectrum will be commissioned daily to provide insights into the unfolding drama of the new 21 st Century Wales – whether it be Labour’s leadership election, constitutional change, the climate change debate, arguments about education, or the ongoing problems, successes and shortcomings of the Welsh economy. There will be more scope, too, for interactive debate, and a special section for IWA members. Plus: Information about the IWA’s branches, events, and publications. This will be the must see and must use Welsh website. clickonwales and see where it takes you. clickonwales and see how far you go. The Institute of Welsh Affairs gratefully acknowledges core funding from the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust , the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation and the Waterloo Foundation . The following organisations are corporate members: Private Sector • Principality Building Society • The Electoral Commission Certified Accountants • Abaca Ltd • Royal Hotel Cardiff • Embassy of Ireland • Autism Cymru • Beaufort Research • Royal Mail Group Wales • Fforwm • Cartrefi Cymunedol / • Biffa Waste Services Ltd • RWE NPower Renewables • The Forestry Commission Community Housing Cymru • British Gas • S. -

(Public Pack)Supplementary Agenda Agenda Supplement for North

Public Document Pack Supplementary Agenda Meeting: North Yorkshire Police, Fire and Crime Panel Venue: Remote Meeting held via Microsoft Teams Date: Wednesday, 24 March 2021 at 2.00 pm Pursuant to The Local Authorities and Police and Crime Panels (Coronavirus) (Flexibility of Local Authority Police and Crime Panel Meetings) (England and Wales) Regulations 2020, this meeting will be held using video conferencing with a live broadcast to the Council’s YouTube site. Further information on this is available on the committee pages on the Council website - https://democracy.northyorks.gov.uk The meeting will be available to view once the meeting commences, via the following link - www.northyorks.gov.uk/livemeetings Business Item Number: 10 (b) Supporting information from the Police, Fire and Crime Commissioner (Pages 3 - 20) 10 (c) Personal statement from the preferred appointee (Pages 21 - 26) Barry Khan Assistant Chief Executive (Legal and Democratic Services) County Hall Northallerton Wednesday, 17 March 2021 NOTES: (a) Members are reminded of the need to consider whether they have any personal or prejudicial interests to declare on any of the items on this agenda and, if so, of the need to explain the reason(s) why they have any personal interest when making a declaration. The Panel Secretariat officer will be pleased to advise on interest issues. Ideally their views should be sought as soon as possible and preferably prior to the day of the meeting, so that time is available to explore adequately any issues that might arise. Public Question Time The questioner must provide an address and contact telephone number when submitting a request. -

Scotland Yard's Flying Squad 100 Years of Crime Fighting

PRESS RELEASE Pen & Sword Books Ltd Matthew Potts, 47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS Tel: +44 01226734679 Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk Email: [email protected] Scotland Yard's Flying Squad 100 Years of Crime Fighting Author: Dick Kirby Highlights Published to coincide with the Flying Squad’s Centenary No-holds barred history of the most celebrated police unit in the Country Written by acclaimed ex-Scotland Yard author with unrivalled contacts. Gripping accounts of police investigations into notorious crimes and criminals. The Flying Squad’s exploits have been frequently dramatised by TV, film and other media. Published to coincide with the Flying Squad’s Centenary No-holds barred history of the most celebrated police unit in the Country Written by acclaimed ex-Scotland Yard author with unrivalled contacts. NEW BOOK RELEASE Gripping accounts of police investigations into notorious crimes and criminals. RRP: £14.99 The Flying Squad’s exploits have been frequently dramatised by TV, film and other media. ISBN: 9781526752178 Strong possibility of supporting TV documentary and serialisation 288 PAGES · PAPERBACK About the Author PUBLISHED: JUNE 2020 PEN & SWORD TRUE CRIME DICK KIRBY was born in the East End of London and joined the Metropolitan Police in 1967. Half of his twenty-six years’ service was spent with Scotland Yard’s Serious Crime Squad and the Flying Squad. Kirby contributes to newspapers and magazines on a regular basis, as well as appearing on television and radio. The Guv’nors, The Sweeney, Scotland Yard’s Ghost Squad, The Brave Blue Line, Death on the Beat, Scourge of Soho, London’s Gangs at War and Scotland Yard’s Gangbuster are all published under the Pen & Sword True Crime imprint and he has further other published works to his credit. -

Successful Bids to the Police Innovation Fund 2016 to 2017

SUCCESSFUL BIDS TO THE POLICE INNOVATION FUND 2016/17 Bid 2016/17 Lead Force Other partners Bid Name / Details No. Award National Centre for Cyberstalking Research (NCCR) – University of Bedfordshire Cyberharassment: University of Liverpool Bedfordshire Platform for Evidence Nottingham Trent University £461,684.00 47 Gathering, Assessing Police Victim Support Risk & Managing Hampshire Stalking Policing Consultancy Clinic Paladin Greater Manchester Police Dyfed-Powys PCC Cambridgeshire Constabulary University of Cambridge BeNCH Community Rehabilitation Company Crown Prosecution Service Evidence-based Local authorities Cambridgeshire approach to deferred Health system £250,000.00 36 prosecution linked to Constabulary Criminal Justice Board devolution in West Midlands Police Cambridgeshire. Hampshire Constabulary Hertfordshire Constabulary Leicestershire Police Staffordshire Police West Yorkshire Police Ministry of Justice/NOMS Warwickshire Police Cheshire Integrated Force West Mercia Police £303,000.00 122 Communications Constabulary West Mercia Fire and Rescue Solution Cheshire Fire and Rescue Fire and Rescue Services Cheshire (FRS) through the Chief Fire National Air Service for 140 £120,100.00 Constabulary Officers’ Association (CFOA) emergency services Association of Ambulance (Category 1 and 2) Chief Executives (AACE) City of London Metropolitan Police Service False identity data £525,000.00 62 Warwickshire Police Police capture and sharing Barclays Bank Metropolitan Police Service Serious Fraud Office Public/private Crown Prosecution -

Greater Manchester Police

WEST MIDLANDS POLICE JOB DESCRIPTION POST TITLE: Chief Firearms Instructor Band E LPU/DEPARTMENT: Operations Firearms Unit RESPONSIBLE TO: Chief Superintendent Operations Department RESPONSIBLE FOR: Sergeant, Constable and Police Staff Firearms Instructors; Business Support Manager; Armourer. AIM OF JOB: Management of the Firearms Training Unit in WMP. Management of training for all AFOs & Firearms Commanders VETTING LEVEL: SC level MAIN DUTIES AND RESPONSIBILITIES MANAGING STAFF ▪ Manage and develop staff within the unit. ▪ Manage Policy Compliance Unit. ▪ Maintain an awareness of staff welfare needs. ▪ Monitor the supervision of officers and police staff receiving training. ▪ Monitor the delivery of training. ▪ Manage staff performance ,ensuring that annual and interim meetings take place and objectives are agreed and actioned. ▪ Identify strengths, weaknesses and training needs. ▪ Implement and monitor the West Midlands Police Equal Opportunities Policy with regard to managing staff and provision of services. 1 | P a g e Version 1.2 April 2015 ADMINISTRATION ▪ To oversee the collation and production of performance and statistical returns. ▪ To be responsible for the management of devolved budgets. ▪ To represent the force at local, regional and national conferences where applicable to the post holder ▪ To provide reports and comprehensive working papers including making recommendations for improvements or amendments to systems within the department. ▪ Plan and prepare annual Firearms Training plan. ▪ Ensure compliance with College of Policing Firearms Training Licensing requirements and submission of annual Quality Assurance Management Systems documentation. ▪ Evaluate all firearms refresher training. Signing of all Risk Assessments. ▪ Evaluate all firearm training - new learning ▪ Process paper work and maintain records of training given utilising computer data base system JML Chronicle. -

List of Police, Prison & Court Personnel Charged Or Convicted Of

List of Police, Prison & Court Personnel charged or convicted of an offence 2009 to 2021 – V40 16/03/2021 - (Discard all previous versions) Please only share this original version. Consent is not given to edit or change this document in any way. - [email protected] © Date Name Police Force Offence Result Source 16th March 2021 PC Wayne Couzens Metropolitan Police Charged with murder Proceeding Source: 15th March 2021 Sgt Ben Lister West Yorkshire Police Charged with rape Proceeding Source: 9th March 2021 PC Jonathan Finch Hampshire Police Gross Misconduct (sexual exposure) Sacked Source: 2nd March 2021 PC Olivia Lucas Hampshire Police Gross Misconduct (Lying) Resigned Source: 22nd Feb 2021 PC Tasia Stephens South Wales Police Drink Driving Banned for 15 months Source: 17th Feb 2021 Ursula Collins Metropolitan Police Charged - 8 counts of misconduct Proceeding Source: 15th Feb 2021 PO Paul Albertsen HMP Salford Theft from prisons Jailedfor 15 months Source: 15th Feb 2021 PO Paul Hewitt HMP Salford Theft from prisons Jailed for 15 months Source: 10th Feb 2021 PC Andrew Sollars Hampshire Police Sexual assault Three months suspended Source: 2nd Feb 2021 PC Alan Friday Cheshire Police Harassment Two year community order Source: 5th Jan 2021 PC Stuart Clarke Nottinghamshire Police Gross Misconduct Resigned Source: 17th Dec 2020 DC Darryl Hart Leicestershire Police Gross Misconduct Final Written Warning Source: 7th Dec 2020 Sgt Rob Adams Sussex Police Gross Misconduct Final Written Warning Source: 2nd Dec 2020 PC William Sampson South -

Building the Picture: an Inspection of Police Information Management

Building the Picture: An inspection of police information management Sussex Police July 2015 © HMIC 2015 ISBN: 978-1-78246-798-4 www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmic Contents 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................... 3 Why information management is important ............................................................ 3 2. Findings for Sussex Police .............................................................................. 7 General ................................................................................................................... 7 Collection and recording ......................................................................................... 7 Evaluation ............................................................................................................... 8 Managing police information – common process .................................................... 8 Sharing police information ...................................................................................... 8 Retention, review and disposal ............................................................................... 9 3. Thematic report – National recommendations ............................................. 10 To the Home Office and the National Lead for Information Management Business Area ...................................................................................................................... 10 To chief constables .............................................................................................. -

Manchester Arena Inquiry Day 66 February 23, 2021 Opus 2

Manchester Arena Inquiry Day 66 February 23, 2021 Opus 2 - Official Court Reporters Phone: +44 (0)20 3008 5900 Email: [email protected] Website: https://www.opus2.com February 23, 2021 Manchester Arena Inquiry Day 66 1 Tuesday, 23 February 2021 1 the coming into effect of that plan in July 2012? 2 (10.15 am) 2 A. I was, yes. 3 MR GREANEY: Sir, good morning. I’m sorry we are starting 3 Q. Still dealing with matters of background, in 2012 when 4 a few minutes later than even the delayed start today; 4 you joined the unit, how many inspectors were there 5 there was a good reason for that. The gentleman in the 5 in the firearms unit? 6 witness box is someone that we heard a good deal about 6 A. There were eight in total , sir . 7 yesterday, it ’s Inspector Simon Lear, and I will ask 7 Q. Sir, for your information, I ’m in the first statement of 8 that he be sworn by Andrew, please. 8 Inspector Lear at paragraph 2. 9 INSPECTOR SIMON LEAR (sworn) 9 So there were eight inspectors? 10 Questions from MR GREANEY 10 A. Yes. 11 MR GREANEY: Would you begin, please, by telling us what 11 Q. Over time, was there any impact upon the number of 12 your full name is? 12 inspectors within the unit? 13 A. Simon Andrew Lear. 13 A. Over the next couple of years, sir , it went down from 14 Q. Are you an inspector with Greater Manchester Police? 14 eight to five and then finished at three. -

Devon and Cornwall Police Guidelines

NOT PROTECTIVELY MARKED DEVON & CORNWALL C O N S T A B U L A R Y Force Policy & Procedure Guideline POLICE USE OF FIREARMS: POLICY AND OPERATIONAL Reference Number D83 Policy Version Date 15 July 2005 Review Date 1 May 2006 Policy Ownership: Crime Department Portfolio Holder: Assistant Chief Constable (O) Links or overlaps with other policies: D73 Negotiators D84 Police Use of Firearms : Training D144 Police Dogs & their use D147 TPAC D241 Post Incident Procedures (Firearms) D242 Use of Handheld Digital Recorders DEVON & CORNWALL CONSTABULARY POLICY & PROCEDURES D83 POLICE USE OF FIREARMS: POLICY AND OPERATIONAL VERSION DATED 15/07/05 1.0 POLICY IDENTIFICATION 1.1 This policy has been drafted in accordance with the principles of Human Rights legislation, Race Relations (Amendment) Act 2000 and Freedom of Information Act 2000. Public disclosure is approved unless where otherwise indicated and justified by relevant exemptions. 15/07/05 Force Publication Scheme NOT PROTECTIVELY MARKED 2.0 POLICY STATEMENTS/INTENTIONS (FOIA – OPEN) 2.1 This guideline outlines the Firearms Strategy for the Devon & Cornwall Constabulary. It sets out how and by whom the strategy will be delivered as well as giving guidance on specific operational circumstances. 3.0 INTRODUCTION (FOIA – OPEN) 3.1 It is the policy of the Devon & Cornwall Constabulary, at all incidents involving the police use of firearms to comply with the guidelines detailed in the ACPO Manual of Guidance on the Police Use of Firearms. 3.2 In keeping with the Manual of Guidance, the underlying principle for the interpretation of this guideline should be the application of common sense, reinforced by teamwork. -

Policing London Business Plan 2012-15

Appendix 1 APPENDIX 1 METROPOLITAN POLICE AUTHORITY METROPOLITAN POLICE SERVICE DRAFT POLICING LONDON BUSINESS PLAN 2012-15 APPENDIX 1 THIS PAGE IS INTENTIONALLY BLANK PLBP 2012-15 APPENDIX 1 MESSAGE FROM THE METROPOLITAN POLICE AUTHORITY (MPA) [TO BE AGREED] The Policing London Business Plan is the key document explaining how the Metropolitan Police Authority (MPA) and the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) will deliver policing services to London next year. We have jointly agreed it and will work together to make sure that London sees crime falling even further. The MPA document Met Forward sets the MPA’s strategic priorities and provides context for the Met to support delivery of the Policing London Business Plan 2012-15. Met Forward describes the future priorities for policing in London, based on an analysis of economic, political, legislative and demographic trends, and of course most importantly, what people tell us. We created Met Forward in 2009, and refreshed it in 2011, to guide the Met police in tackling the issues that matter most to Londoners: fighting crime and reducing criminality; increasing confidence in policing; and giving us better value for money. This was the first time that the Authority had clearly set out its priorities. Londoners consistently tell us that they want to see more police officers on their streets and we are committed to maintaining front line officer numbers and tackling the crimes that you have told us you worry about most – violent crime, crimes against property and anti-social behaviour. Public buy-in is essential. To deliver our vision of a police service that meets your needs, the Authority and the Met will make sure we engage with as many people and groups as we possibly can.