"Veronica and Betty Are Going Steady!": Queer Spaces in the Archie Comics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jughead Jones. Copy

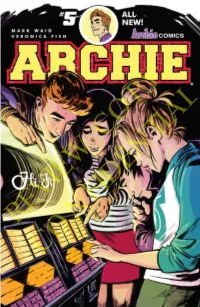

COPY: REVIEW CONFIDENTIAL Archie Andrews and Betty Cooper haven’t spoken since the infamous #LipstickIncident that broke them apart over the summer, and Betty’s having a rough time seeing him get over their relationship and move on with new girl Veronica Lodge. Even worse, their budding relationship is making Archie’s best friend Jughead Jones downright crazy. They have to step in and do SOMETHING, but Jughead’sCOPY: not so sure about who they’ve chosen to do their dirty work… STORY BY ART BY MARK WAID VERONICA FISH COLORING BY LETTERING BY ANDRE SZYMANOWICZ JACK MORELLI With JEN VAUGHN REVIEWPUBLISHER EDITOR JON GOLDWATER MIKE PELLERITO Publisher / Co-CEO: Jon Goldwater Co-CEO: Nancy Silberkleit President: Mike Pellerito Co-President / Editor-In-Chief: Victor Gorelick Chief Creative Officer: Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa Chief Operating Officer: William Mooar Chief Financial Officer:CONFIDENTIAL Robert Wintle SVP – Publishing and Operations: Harold Buchholz SVP – Publicity & Marketing: Alex Segura SVP – Digital: Ron Perazza Director of Book Sales & Operations: Jonathan Betancourt Production Manager: Stephen Oswald Production Assistant: Isabelle Mauriello Proofreader / Editorial Assistant: Jamie Lee Rotante ARCHIE (ISSN:07356455), Vol. 2, No. 5, February, 2016. Published monthly by ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS, INC., 629 Fifth Avenue, Suite 100, Pelham, New York 10803-1242. Jon Goldwater, Publisher/Co-CEO; Nancy Silberkleit, Co-CEO; Mike Pellerito, President; Victor Gorelick, Co-President. ARCHIE characters created by John L. Goldwater. The likenesses of the original Archie characters were created by Bob Montana. Single copies $3.99. Subscription rate: $47.88 for 12 issues. All Canadian orders payable in U.S. funds. “Archie” and the individual characters’ names and likenesses are the exclusive trademarks of Archie Comic Publications, Inc. -

The Charismatic Leadership and Cultural Legacy of Stan Lee

REINVENTING THE AMERICAN SUPERHERO: THE CHARISMATIC LEADERSHIP AND CULTURAL LEGACY OF STAN LEE Hazel Homer-Wambeam Junior Individual Documentary Process Paper: 499 Words !1 “A different house of worship A different color skin A piece of land that’s coveted And the drums of war begin.” -Stan Lee, 1970 THESIS As the comic book industry was collapsing during the 1950s and 60s, Stan Lee utilized his charismatic leadership style to reinvent and revive the superhero phenomenon. By leading the industry into the “Marvel Age,” Lee has left a multilayered legacy. Examples of this include raising awareness of social issues, shaping contemporary pop-culture, teaching literacy, giving people hope and self-confidence in the face of adversity, and leaving behind a multibillion dollar industry that employs thousands of people. TOPIC I was inspired to learn about Stan Lee after watching my first Marvel movie last spring. I was never interested in superheroes before this project, but now I have become an expert on the history of Marvel and have a new found love for the genre. Stan Lee’s entire personal collection is archived at the University of Wyoming American Heritage Center in my hometown. It contains 196 boxes of interviews, correspondence, original manuscripts, photos and comics from the 1920s to today. This was an amazing opportunity to obtain primary resources. !2 RESEARCH My most important primary resource was the phone interview I conducted with Stan Lee himself, now 92 years old. It was a rare opportunity that few people have had, and quite an honor! I use clips of Lee’s answers in my documentary. -

The World of Archie Comics Archive Access to 100+ Titles from Archie Comics, Spanning the Early 1940S to 2020

PROQUEST DATASHEET The World of Archie Comics Archive Access to 100+ titles from Archie Comics, spanning the early 1940s to 2020 An unprecedented digital collection offering access to the runs of more than 100 publications from Archie Comics. This is one of the longest running, best-known comic stables, spanning the early 1940s to 2020. Alongside the flagship title, Archie, other prominent titles, which have pervaded wider popular culture, include Sabrina: The Teenage Witch, Josie and the Pussycats, Betty & Veronica, and Jughead. The evolution of these publications, across more than • Cross-searchable with ProQuest’s Underground and eight decades, offers insight into changes in society and Independent Comics, Comix, and Graphic Novels, where attitudes pertaining to, for example, issues of race, class, institutions have access to both resources. sexuality/gender, and politics. The archives are also key * Policy is to include each issue from the first and to scan from cover to sources for research in many aspects of comics studies cover. Due to the rarity of this material, however, there will be some gaps and popular culture history, including the development (issues or pages). of the genre, comic art/narrative techniques, and the marketing of comics to particular demographic groups. FEATURES • Coverage spanning 1943 to 2020 – 8 decades of content* • Variety of publication types, from comic book series to graphic novels, annuals, and one-shot comics. • Digital backfiles of more than 100 titles, including several major, long-running series, as well as rare, influential early superhero comics from the 1940s. • Page-image, color digitization maximizes the rich visual content of this material, while detailed article-level indexing enhances the searchability and navigability of this resource. -

6Urlv (Read Ebook) Afterlife with Archie #11 Online

6UrLv (Read ebook) Afterlife With Archie #11 Online [6UrLv.ebook] Afterlife With Archie #11 Pdf Free Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #893377 in eBooks 2016-11-16 2017-12-27 | File size: 36.Mb Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa : Afterlife With Archie #11 before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Afterlife With Archie #11: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. It Just Works- Great FunBy thirdtwin.I'm literally stunned at this combination of characters and situations and how much fun it is. Admit it- it's refreshing to see a note of horror and tension be inserted into Archie's cotton candy world- it's even more fun if you've always found the Archie gangs pervious attitudes and situation in years past..well...irritating. There's certain glee to be found in getting to see these iconic characters put in a situation theyre totally unprepared to face for a change instead of drinking malts and scheming about dates. So in this case zombies are actually a breath of fresh air in this context and the walking dead ironically add new life to the franchise. Even if you don't like Archie this is may be even more enjoyable to read because of what the gang has to face. A+ a gimmick that works for once.1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Very fun, well worth readingBy ChibiNekoI wasn't quite sure what to expect from this. -

Microsoft Visual Basic

$ LIST: FAX/MODEM/E-MAIL: aug 23 2021 PREVIEWS DISK: aug 25 2021 [email protected] for News, Specials and Reorders Visit WWW.PEPCOMICS.NL PEP COMICS DUE DATE: DCD WETH. DEN OUDESTRAAT 10 FAX: 23 augustus 5706 ST HELMOND ONLINE: 23 augustus TEL +31 (0)492-472760 SHIPPING: ($) FAX +31 (0)492-472761 oktober/november #557 ********************************** __ 0079 Walking Dead Compendium TPB Vol.04 59.99 A *** DIAMOND COMIC DISTR. ******* __ 0080 [M] Walking Dead Heres Negan H/C 19.99 A ********************************** __ 0081 [M] Walking Dead Alien H/C 19.99 A __ 0082 Ess.Guide To Comic Bk Letterin S/C 16.99 A DCD SALES TOOLS page 026 __ 0083 Howtoons Tools/Mass Constructi TPB 17.99 A __ 0019 Previews October 2021 #397 5.00 D __ 0084 Howtoons Reignition TPB Vol.01 9.99 A __ 0020 Previews October 2021 Custome #397 0.25 D __ 0085 [M] Fine Print TPB Vol.01 16.99 A __ 0021 Previews Oct 2021 Custo EXTRA #397 0.50 D __ 0086 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.01 14.99 A __ 0023 Previews Oct 2021 Retai EXTRA #397 2.08 D __ 0087 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.02 14.99 A __ 0024 Game Trade Magazine #260 0.00 N __ 0088 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.03 14.99 A __ 0025 Game Trade Magazine EXTRA #260 0.58 N __ 0089 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.04 14.99 A __ 0026 Marvel Previews O EXTRA Vol.05 #16 0.00 D __ 0090 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.05 14.99 A IMAGE COMICS page 040 __ 0091 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.06 16.99 A __ 0028 [M] Friday Bk 01 First Day/Chr TPB 14.99 A __ 0092 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.07 16.99 A __ 0029 [M] Private Eye H/C DLX 49.99 A __ 0093 [M] Sunstone Book 01 H/C 39.99 A __ 0030 [M] Reckless -

![8A1h4 [Pdf Free] Jughead Vol. 1 Online](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0710/8a1h4-pdf-free-jughead-vol-1-online-870710.webp)

8A1h4 [Pdf Free] Jughead Vol. 1 Online

8a1h4 [Pdf free] Jughead Vol. 1 Online [8a1h4.ebook] Jughead Vol. 1 Pdf Free Chip Zdarsky ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #112812 in Books Archie Comics 2016-07-26 2016-07-26Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 10.20 x .40 x 6.70l, .81 #File Name: 1627388931168 pagesArchie Comics | File size: 41.Mb Chip Zdarsky : Jughead Vol. 1 before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Jughead Vol. 1: 2 of 2 people found the following review helpful. Great comic. I read some of the older Jughead ...By CustomerGreat comic. I read some of the older Jughead comics and always enjoyed them. This new run is updated for 2017 without it being forced. The integration of queer characters is well done and wonderful. The spirit of Jughead's imagination and adventures is alive and well in these comics with their fun plotlines and lovely artwork.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. The Archie Reboot continues with Jughead!By samaritanxDecent reboot of a classic charcter, but the stories and artwork were not as strong as some of the other more recent reboots of the other canon Archie characters. I did enjoy seeing The Man from R.I.V.E.R.D.A.L.E. and Captain Pureheart spoofs, even if they were only daydreams in Jughead's imagination.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Jughead's Back!By JanaeI gave this five stars because it gave me everything I want from Jughead and nothing I didn't. -

Comic Books: Superheroes/Heroines, Domestic Scenes, and Animal Images

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 1980 Volume II: Art, Artifacts, and Material Culture Comic Books: Superheroes/heroines, Domestic Scenes, and Animal Images Curriculum Unit 80.02.03 by Patricia Flynn The idea of developing a unit on the American Comic Book grew from the interests and suggestions of middle school students in their art classes. There is a need on the middle school level for an Art History Curriculum that will appeal to young people, and at the same time introduce them to an enduring art form. The history of the American Comic Book seems appropriately qualified to satisfy that need. Art History involves the pursuit of an understanding of man in his time through the study of visual materials. It would seem reasonable to assume that the popular comic book must contain many sources that reflect the values and concerns of the culture that has supported its development and continued growth in America since its introduction in 1934 with the publication of Famous Funnies , a group of reprinted newspaper comic strips. From my informal discussions with middle school students, three distinctive styles of comic books emerged as possible themes; the superhero and the superheroine, domestic scenes, and animal images. These themes historically repeat themselves in endless variations. The superhero/heroine in the comic book can trace its ancestry back to Greek, Roman and Nordic mythology. Ancient mythologies may be considered as a way of explaining the forces of nature to man. Examples of myths may be found world-wide that describe how the universe began, how men, animals and all living things originated, along with the world’s inanimate natural forces. -

GENIUS BRANDS INTERNATIONAL, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, DC 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): July 15, 2020 GENIUS BRANDS INTERNATIONAL, INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Nevada 001-37950 20-4118216 (State or other jurisdiction (Commission File Number) (IRS Employer of incorporation) Identification No.) 190 N. Canon Drive, 4th Fl. Beverly Hills, CA 90210 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (310) 273-4222 ________________________________________________________ (Former name or former address, if changed since last report) Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions (see General Instruction A.2 below): o Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) o Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) o Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) o Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Trading Symbol(s) Name of each exchange on which registered Common Stock, par value $0.001 per share GNUS The Nasdaq Capital Market Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is an emerging growth company as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act of 1933 (§230.405 of this chapter) or Rule 12b-2 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (§240.12b-2 of this chapter). -

An Analysis and Expansion of Queerbaiting in Video Games

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Cultural Analysis and Social Theory Major Research Papers Cultural Analysis and Social Theory 8-2018 Queering Player Agency and Paratexts: An Analysis and Expansion of Queerbaiting in Video Games Jessica Kathryn Needham Wilfrid Laurier University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cast_mrp Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, and the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons Recommended Citation Needham, Jessica Kathryn, "Queering Player Agency and Paratexts: An Analysis and Expansion of Queerbaiting in Video Games" (2018). Cultural Analysis and Social Theory Major Research Papers. 6. https://scholars.wlu.ca/cast_mrp/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Cultural Analysis and Social Theory at Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cultural Analysis and Social Theory Major Research Papers by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Queering player agency and paratexts: An analysis and expansion of queerbaiting in video games by Jessica Kathryn Needham Honours Rhetoric and Professional Writing, Arts and Business, University of Waterloo, 2016 Major Research Paper Submitted to the M.A. in Cultural Analysis and Social Theory in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Master of Arts Wilfrid Laurier University 2018 © Jessica Kathryn Needham 2018 1 Abstract Queerbaiting refers to the way that consumers are lured in with a queer storyline only to have it taken away, collapse into tragic cliché, or fail to offer affirmative representation. Recent queerbaiting research has focused almost exclusively on television, leaving gaps in the ways queer representation is negotiated in other media forms. -

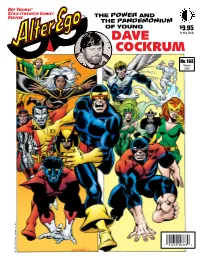

Dave Cockrum Cover Colorist Writer/Editorial: the Red Planet—Mostly in Black-&-White!

Roy Thomas' Xtra-strength Comics Fanzine THE POWER AND THE PANDEMONIUM OF YOUNG $9.95 DAVE In the USA COCKRUM No. 163 March 2020 1 82658 00376 0 Art TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. Vol. 3, No. 163 / March 2020 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editor Jim Amash Design & Layout Christopher Day Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Don’t STEAL our J.T. Go (Assoc. Editor) Digital Editions! C’mon citizen, Comic Crypt Editor DO THE RIGHT THING! A Mom Michael T. Gilbert & Pop publisher like us needs Editorial Honor Roll every sale just to survive! DON’T Jerry G. Bails (founder) DOWNLOAD Ronn Foss, Biljo White OR READ ILLEGAL COPIES ONLINE! Mike Friedrich, Bill Schelly Buy affordable, legal downloads only at www.twomorrows.com Proofreaders or through our Apple and Google Apps! Rob Smentek William J. Dowlding & DON’T SHARE THEM WITH FRIENDS OR POST THEM ONLINE. Help us keep Cover Artist producing great publications like this one! Dave Cockrum Cover Colorist Writer/Editorial: The Red Planet—Mostly In Black-&-White! .. 2 Glenn Whitmore The Genius of Dave & Paty Cockrum .................. 3 With Special Thanks to: Joe Kramar’s 2003 conversation with one of comics’ most amazing couples. Don Allen David Hajdu Paul Allen Heritage Comics Dave Cockrum—A Model Artist....................... 11 Heidi Amash Auctions Andy Yanchus take a personal look back at his friend’s astonishing model work. Pedro Angosto Tony Isabella “One Of The Most Celebrated Richard Arndt Eric Jansen Bob Bailey Sharon Karibian Comicbook Artists Of Our Time” .................... 15 Mike W. Barr Jim Kealy Paul Allen on corresponding with young Dave Cockrum, ERB fan, in 1969-70. -

Chapter Seventeen: the Town That Dreaded Sundown”

CREATED BY Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa EPISODE 2.04 “Chapter Seventeen: The Town That Dreaded Sundown” Archie's viral video stirs up tensions all over town. Jughead and Betty put their heads together to solve a cipher from the Black Hood. WRITTEN BY: Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa, Amanda Lasher DIRECTED BY: Jason Stone ORIGINAL BROADCAST: November 1, 2017 NOTE: This is a transcription of the spoken dialogue and audio, with time-code reference, provided without cost by 8FLiX.com for your entertainment, convenience, and study. This version may not be exactly as written in the original script; however, the intellectual property is still reserved by the original source and may be subject to copyright. EPISODE CAST K.J. Apa ... Archie Andrews Lili Reinhart ... Betty Cooper Camila Mendes ... Veronica Lodge Cole Sprouse ... Jughead Jones Marisol Nichols ... Hermione Lodge Madelaine Petsch ... Cheryl Blossom Mark Consuelos ... Hiram Lodge Casey Cott ... Kevin Keller Mädchen Amick ... Alice Cooper Luke Perry ... Fred Andrews Nathalie Boltt ... Penelope Blossom Peter Bryant ... Principal Waldo Weatherbee Jordan Connor ... Sweet Pea Martin Cummins ... Sheriff Tom Keller Major Curda ... Dilton Doiley Robin Givens ... Sierra McCoy Charles Melton ... Reggie Mantle Vanessa Morgan ... Toni Topaz Lochlyn Munro ... Hal Cooper Amanda Burke ... Ms. Paroo Art Kitching ... Store Clerk Ardy Ramezani ... Football Player Drew Ray Tanner ... Fangs Fogarty Nelson Wong ... Dr. Phylum 1 00:00:08,258 --> 00:00:10,218 [narrator] Previously on Riverdale: 2 00:00:10,301 --> 00:00:11,177 [gunshot] 3 00:00:11,261 --> 00:00:14,139 [Alice] He calls himself the Black Hood. He wants us to publish this letter. -

The Blue and Gold Riverdale High School’S Student Newspaper Editor: Betty Cooper

The Blue and Gold Riverdale High School’s Student Newspaper Editor: Betty Cooper Volume 47, Issue 23 Former Principal Ross passes away as age 67 By Jughead Jones Former Principal Marshal Ross Thursday. passed away Saturday at the Former students who would age of 67. He was a polarizing like to pay tribute Principal figure in the Riverdale commu- Ross are asked to donate to nity after hiring the Southside Students with Purpose in lieu Serpents for a semester for of sending flowers. security . Principal Ross quick- ly moved to Greendale after his Caption describing picture or one year as the Riverdale Prin- graphic. cipal. He returned to his true love of teaching shop class. He loved cars and helping students learn how to be responsible He leaves behind a sister Mag- gie (Ross) Fairview, niece Cherry Fairview, nephew Mark Fairview. His services will be held at the Spellman funeral home and crematory in Greendale on Wednesday and burial on Special points of interest: Riverdale debate team heads to regionals Rabbits attack Maple Trees! Badminton team By Betty Cooper beats Baxter High Maple Syrup Blossom Maple Syrup may be (scrambles for a way) to get a warning to anyone who might shortage in Riverdale in serious financial trouble after rid of the rabbits. The tree- have brought the tree-eating Josie and The Pussy- a large number of tree-eating eating rabbits appear to be a rabbits to Riverdale. “You will cats suddenly cancel rabbits were discovered eating variety that is much larger get what is coming to you!" dance performance their valuable maple trees.