Participatory Vulnerability Analysis in the North of the Gaza Strip

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protection of Civilians – Weekly Briefing Notes 22 – 28 February 2006

U N I TOCHA E D Weekly N A Briefing T I O NotesN S 22 – 28 February 2006 N A T I O N S| 1 U N I E S OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS P.O. Box 38712, East Jerusalem, Phone: (+972) 2-582 9962 / 582 5853, Fax: (+972) 2-582 5841 [email protected], www.ochaopt.org Protection of Civilians – Weekly Briefing Notes 22 – 28 February 2006 Of note this period • IDF military operations in Balata camp (Nablus) continued. Four Palestinians including a child were killed and 15 others injured. Two IDF soldiers were also injured in the operation. • A large number of Palestinians injured – including in demonstrations against the construction of the Barrier in Ramallah and Jerusalem and confrontations between the IDF and Palestinian stone throwers in the West Bank. • High number of flying checkpoints observed throughout the West Bank, particularly in Qalqiliya, Nablus and Hebron governorates. 1. Physical Protection Casualties1 80 60 40 20 0 Children Women Injuries Deaths Deaths Deaths Palestinians 71 8 1 - Israelis 10 - - - Internationals ---- • 22 February: IDF soldiers beat and injured a 21-year-old Palestinian in H1 area of Hebron city (Hebron). • 22 February: The IDF injured a 15-year-old Palestinian minor after opening fire towards Palestinian stone throwers in Bani Na’im (Hebron). • 22 February: Palestinians injured one Israeli after opening fire at an Israeli plated vehicle passing on Road 55 near Ázzun (Qalqiliya). • 22 February: The IDF injured one Palestinian man after opening fire at Huwwara checkpoint (Nablus) during unrest at the checkpoint caused by long delays. -

Joint Alternative Report Submitted by The

Joint Alternative Report submitted by the Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions (COHRE) and Al-Haq to the Human Rights Committee on the occasion of the consideration of the Third Periodic Report of Israel Israel’s violations of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights with regard to house demolitions, forced evictions and safe water and sanitation in the Occupied Palestinian Territory and Israel Submitted June 2010 COHRE and Al-Haq are independent non-governmental organisations in UN ECOSOC Special Consultative Status Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................3 2. ISRAEL’S LEGAL OBLIGATIONS IN THE OPT........................................4 3. FORCED EVICTIONS AND HOUSE DEMOLITIONS .............................6 3.1 Punitive House Demolitions..................................................................................6 3.1.1 West Bank ......................................................................................................6 3.1.2 Gaza .............................................................................................................11 3.2 Administrative House Demolitions......................................................................16 3.2.1 West Bank...................................................................................................16 3.2.2 Israel: Mixed Cities.....................................................................................24 3.3. Other Forced Evictions......................................................................................25 -

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 05-20-2009 I, Shadi Y. Saleh , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master in Architecture It is entitled: Designing by Community Participation: Meeting the Challenges of the Palestinian Refugee Camps Shadi Saleh Student Signature: This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Elizabeth Riorden Thomas Bible Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Elizabeth Riorden Designing by Community Participation: Meeting the Challenges of the Palestinian Refugee Camps A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advance Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Architecture In the school of Architecture and Interior design Of the College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning 2009 By Shadi Y. Saleh Committee chair Elizabeth Riorden Thomas Bible ABSTRACT Palestinian refugee camps in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria are the result of the sudden population displacements of 1948 and 1967. After 60 years, unorganized urban growth compounds the situation. The absence of state support pushed the refugees to take matters into their own hands. Currently the camps have problems stemming from both the social situation and the degradation of the built environment. Keeping the refugee camps in order to “represent” a nation in exile does not mean to me that there should be no development. The thesis seeks to make a contribution in solving the social and environmental problems in a way that emphasizes the Right of Return. -

Palestinian Forces

Center for Strategic and International Studies Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy 1800 K Street, N.W. • Suite 400 • Washington, DC 20006 Phone: 1 (202) 775 -3270 • Fax : 1 (202) 457 -8746 Email: [email protected] Palestinian Forces Palestinian Authority and Militant Forces Anthony H. Cordesman Center for Strategic and International Studies [email protected] Rough Working Draft: Revised February 9, 2006 Copyright, Anthony H. Cordesman, all rights reserved. May not be reproduced, referenced, quote d, or excerpted without the written permission of the author. Cordesman: Palestinian Forces 2/9/06 Page 2 ROUGH WORKING DRAFT: REVISED FEBRUARY 9, 2006 ................................ ................................ ............ 1 THE MILITARY FORCES OF PALESTINE ................................ ................................ ................................ .......... 2 THE OSLO ACCORDS AND THE NEW ISRAELI -PALESTINIAN WAR ................................ ................................ .............. 3 THE DEATH OF ARAFAT AND THE VICTORY OF HAMAS : REDEFINING PALESTINIAN POLITICS AND THE ARAB - ISRAELI MILITARY BALANCE ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ .... 4 THE CHANGING STRUCTURE OF PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY FORC ES ................................ ................................ .......... 5 Palestinian Authority Forces During the Peace Process ................................ ................................ ..................... 6 The -

Flood Vulnerability Assessment Using Multi- Criteria Approach: a Case Study from North Gaza

اﻟﺠـﺎﻣﻌــــــــــﺔ اﻹﺳـــــﻼﻣﯿــﺔ ﺑﻐــﺰة The Islamic University of Gaza ﻋﻤﺎدة اﻟﺒﺤﺚ اﻟﻌﻠﻤﻲ واﻟﺪراﺳﺎت اﻟﻌﻠﯿﺎ Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies ﻛـﻠﯿــــــــــــــــــــﺔ اﻟﮭﻨﺪﺳــــــــــــــــــﺔ Faculty of Engineering Master of Water Resources Management ﻣﺎﺟﺴﺘﯿـــــﺮ إدارة ﻣﺼـــــــﺎدر ﻣﯿــــﺎه Flood Vulnerability Assessment Using Multi- Criteria Approach: A Case Study from North Gaza ﺘﻘییم ﻤواطن ﻀعﻒ أﻤﺎﻛن اﻟتﻌرض ﻟﻠﻔیضﺎﻨﺎت �ﺎﺴتخدام ﻨﻬﺞ ﻤتﻌدد اﻟمﻌﺎﯿیر: دراﺴﺔ ﺤﺎﻟﺔ ﺸمﺎل ﻗطﺎع ﻏزة By Dalya Taysir Matar Supervised by Dr. Khalil Al Astal Dr. Tamer Eshtawi Assistant Professor in Water Assistant Professor in Water Resources Engineering Resources Engineering A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Water Resources Management March /2019 إﻗــــــــــــــرار أﻨﺎ اﻟموﻗﻊ أدﻨﺎﻩ ﻤﻘدم اﻟرﺴﺎﻟﺔ اﻟتﻲ ﺘحمﻞ اﻟﻌنوان: Flood Vulnerability Assessment Using Multi-Criteria Approach: A Case Study from North Gaza ﺘﻘییم ﻤواطن ﻀعﻒ أﻤﺎﻛن اﻟتﻌرض ﻟﻠﻔیضﺎﻨﺎت �ﺎﺴتخدام ﻨﻬﺞ ﻤتﻌدد اﻟمﻌﺎﯿیر: دراﺴﺔ ﺤﺎﻟﺔ ﺸمﺎل ﻗطﺎع ﻏزة أﻗر �ﺄن ﻤﺎ اﺸتمﻠت ﻋﻠیﻪ ﻫذﻩ اﻟرﺴﺎﻟﺔ إﻨمﺎ ﻫو ﻨتﺎج ﺠﻬدي اﻟخﺎص، �ﺎﺴتثنﺎء ﻤﺎ ﺘمت اﻹﺸﺎرة إﻟیﻪ ﺤیثمﺎ ورد، وأن ﻫذﻩ اﻟرﺴﺎﻟﺔ �كﻞ أو أي ﺠزء ﻤنﻬﺎ ﻟم �ﻘدم ﻤن ﻗبﻞ ا ﻻ ﺨ ر� ن ﻟنیﻞ درﺠﺔ أو ﻟﻘب ﻋﻠمﻲ أو �حثﻲ ﻟدى أي ﻤؤﺴسﺔ ﺘﻌﻠیمیﺔ أو �حثیﺔ أﺨرى. Declaration I understand the nature of plagiarism, and I am aware of the University’s policy on this. The work provided in this thesis, unless otherwise referenced, is the researcher's own work and has not been submitted by others elsewhere for any other degree or qualification. اﺴم اﻟطﺎﻟب: داﻟﯿﮫ ﺗﯿﺴﯿﺮ ﻣﻄﺮ :Student's name اﻟتوﻗیﻊ: :Signature ا ﻟ ت ﺎ ر� ﺦ : :Date I Abstract Flooding is one of the prevalent natural disasters that cause serious damage to the population. -

Beneficiary and Community Perspectives on the Palestinian National Cash Transfer Programme

TRANSFORMING COUNTRY BRIEFING CASH TRANSFERS Beneficiary and community perspectives on the Palestinian National Cash Transfer Programme transformingcashtransfers.org Introduction transformingcashtransfers.org Our research aimed to explore the perceptions of cash transfer programme beneficiaries and implementers and other community members, in order to ensure their views are better reflected in policy and programming. Introduction transformingcashtransfers.org There is growing evidence internationally of positive links Key points: between social protection and poverty and vulnerability reduction. However, there has been limited recognition of the • De-developmental policies, recurring social inequalities that perpetuate poverty, such as gender insecurity and dependency on donor inequality, unequal citizenship status and displacement funding are among the key challenges through conflict, and the role social protection can play in in advancing social protection in the tackling these interlinked socio-political vulnerabilities. Occupied Palestinian Territories. • The Palestinian National Cash Transfer This country briefing synthesises qualitative research focusing Programme is an important but on beneficiary and community perceptions of the Palestinian limited component of female-headed National Cash Transfer Programme (PNCTP) in Gaza1 and households’ coping repertoires. West Bank2, as part of a broader research project in five countries (Kenya, Mozambique, OPT, Uganda and Yemen) by • Programme governance requires urgent the Overseas Development -

Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia As Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2013): 6.14 | Impact Factor (2015): 6.391 Urban Planning Analyses of Refugee Camps, Jabalia as Case Study-Gaza Strip, Palestine Dr. Usama Ibrahim Badawy1, Dr Ra’ed A. Salha2, Dr. Muain Qasem Jawabrah3, Amjad Jarada4 Mohammed A. EL Hawajri5 1Former Professor of Architecture, Birzeit University Palestine, works currently at UNRWA 2Assistant Professor, Islamic University of Gaza in Geography and GIS Palestine 3Assistance Professor, Architecture Department, Birzeit University Palestine 4Researcher in Infrastructure Planning and Development works currently at UNRWA, G, 5Researcher Geography subjects, works currently as teacher by the Ministry of Education Abstract: The Gaza Strip is a tight area with more than 1.8 million inhabitants. Since the beginning of the last century, and as other Palestinian areas, Gaza Strip was subject to direct occupation. The occupation tightened laws and regulations and increased obstacles, meanwhile it established settlements in a method that besieges existing Palestinian urban areas and leads them to develop in a way that serves the occupation, particularly the security side. This research begins with background information on Palestinian refugees in Gaza, sees that camp Improvement Strategies should called for adoption of the future urban planning, increasing the accommodation capacity of the built-up area, activating the environmental resources protection laws and played down the issue of the land properties when preparing the comprehensive plans. In this study reviews options for addressing the problems faced by Palestinian refugees in Gaza, Recommendations: After discussing the topic through a analyses of the Current Conditions , Land availability, Population distribution, Land requirements, Overcrowding, Public Spaces problems inside the camps , Sustainability in Gaza Strip, socio-economic situation , Unemployment problem and Population density in Jabalia Camp. -

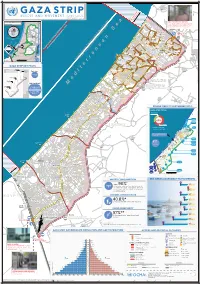

North Gaza ¥ August 2011 ¥ 3 3 Mediterranean Sea No-Go Zone

No Fishing Zone 1.5 nautical miles 3 nautical miles X Y Z AA BB CC DD EE FF X Y Z AA BB CC DD EE FF Yad Mordekhai Yad Mordekhai 2 United Nations OfficeAs-Siafa for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs As-Siafa 2 ACCESS AND MOVEMENT - NORTH GAZA ¥ auGUST 2011 ¥ 3 3 Mediterranean Sea No-Go Zone Al-Rasheed Netiv ha-Asara Netiv ha-Asara High Risk Zone Temporary Wastewater 4 Treatment Lagoons 4 Erez Crossing Erez Crossing Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Beit Hanoun) (Beit Hanoun) Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Umm An-Naser) (Umm An-Naser) Beit Lahia 5 Wastewater 5 Treatment Plant Beit Lahiya Beit Lahiya 6 6 'Izbat Beit Hanoun 'Izbat Beit Hanoun Al Mathaf Hotel Al-Sekka Al Karama Al Karama El-Bahar Beit Lahia Main St. Arc-Med Hotel Al-Faloja Sheikh Zayed Beit Hanoun Housing Project Beit Hanoun Madinat al 'Awda 7 v®Madinat al 'Awda 7 Beit Hanoun Jabalia Camp v® Industrial Jabalia Camp 'Arab Maslakh Zone Beit Hanoun 'Arab Maslakh Kamal Edwan Beit Lahya Beit Lahya Abu Ali Eyad Kamal Edwan Hospital Al-Naser Al-Saftawi Hospital Khalil Al-Wazeer Ahmad Sadeq Ash Shati' Camp Said El-Asi Jabalia Jabalia An Naser 8 Al-quds An Naser 8 El-Majadla Ash Sheikh Yousef El-Adama Ash Sheikh Al-Sekka Radwan Radwan Falastin Khalil El-Wazeer Al Deira Hotel Ameen El Husaini Heteen Salah El-Deen ! Al-Yarmook Saleh Dardona Abu Baker Al-Razy Palestine Stadium Al-Shifa Al-Jalaa 9 9 Hospital ! Al-quds Northern Rimal Al-Naffaq Al-Mashahra El-Karama Northern Rimal Omar El-Mokhtar Southern Rimal Al-Wehda Al-Shohada Al Azhar University Ad Daraj G Ad Daraj o v At Tuffah e At Tuffah 10 r 10 n High Risk Zone Islamic ! or Al-Qanal a University Yafa t e Haifa Jamal Abdel Naser Al-Sekka 500 meter NO-Go Zone Salah El-Deen Gaza Strip Beit Lahiya Al-Qahera Khalil Al-Wazeer J" Boundar J" y JabalyaJ" Al-Aqsa As Sabra Gaza City Beit Hanun Gaza City Marzouq GazaJ" City Northern Gaza Al-Dahshan Wire Fence Al 'Umari11 Wastewater 11 Mosque Moshtaha Treatment Plant Tal El Hawa Ijdeedeh Ijdeedeh Deir alJ" Balah Old City Bagdad Old City Rd No. -

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n . -

National Report, State of Palestine United Nations

National Report, State of Palestine United Nations Conference on Human Settlements (Habitat III) 2014 Ministry of Public Works and Housing National Report, State of Palestine, UN-Habitat 1 Photo: Jersualem, Old City Photo for Jerusalem, old city Table of Contents FORWARD 5 I. INTRODUCTION 7 II. URBAN AGENDA SECTORS 12 1. Urban Demographic 12 1.1 Current Status 12 1.2 Achievements 18 1.3 Challenges 20 1.4 Future Priorities 21 2. Land and Urban Planning 22 2. 1 Current Status 22 2.2 Achievements 22 2.3 Challenges 26 2.4 Future Priorities 28 3. Environment and Urbanization 28 3. 1 Current Status 28 3.2 Achievements 30 3.3 Challenges 31 3.4 Future Priorities 32 4. Urban Governance and Legislation 33 4. 1 Current Status 33 4.2 Achievements 34 4.3 Challenges 35 4.4 Future Priorities 36 5. Urban Economy 36 5. 1 Current Status 36 5.2 Achievements 38 5.3 Challenges 38 5.4 Future Priorities 39 6. Housing and Basic Services 40 6. 1 Current Status 40 6.2 Achievements 43 6.3 Challenges 46 6.4 Future Priorities 49 III. MAIN INDICATORS 51 Refrences 52 Committee Members 54 2 Lists of Figures Figure 1: Percent of Palestinian Population by Locality Type in Palestine 12 Figure 2: Palestinian Population by Governorate in the Gaza Strip (1997, 2007, 2014) 13 Figure 3: Palestinian Population by Governorate in the West Bank (1997, 2007, 2014) 13 Figure 4: Palestinian Population Density of Built-up Area (Person Per km²), 2007 15 Figure 5: Percent of Change in Palestinian Population by Locality Type West Bank (1997, 2014) 15 Figure 6: Population Distribution -

Weekly Report on Israeli Human Rights Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (10 – 16 November 2016) | Palestinian Center for Human Rights

11/17/2016 Weekly Report On Israeli Human Rights Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (10 – 16 November 2016) | Palestinian Center for Human Rights Weekly Report On Israeli Human Rights Violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (10 – 16 November 2016) Israeli forces continue systematic crimes in the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt) (10 – 16 November 2016) Israeli forces continued to use excessive force in the oPt 6 Palestinian civilians, including 2 children, were wounded in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. House demolitions on grounds of collective punishment. A room was closed with concrete in Yatta, south of Hebron. Israeli forces conducted 64 incursions into Palestinian communities in the West Bank and 6 ones in occupied Jerusalem. 57 civilians, including 15 children and a woman, were arrested. Fifteen of them, including 12 children and the woman, were arrested in occupied Jerusalem. The Health Improvement Program’s office in Ramallah was raided and some of its content were confiscated. Israeli forces continued to target Palestinian fishermen in the Gaza Strip Sea. 2 fishermen were arrested and their fishing boat was confiscated, north of the Gaza Strip. Israeli forces continued their efforts to create Jewish majority in occupied East Jerusalem. 2 residential apartments in alMukaber Mount and 2 stores in Beit Hanina were selfdemolished by their owners. 2 barracks, an agricultural room and a mosque foundation in Silwan and Sour Baher villages were demolished. Settlement activities continued in the West Bank. 2 agricultural rooms in Qalqilya and a residential tent, a social service centre and a well, south of Hebron, were demolished. -

Readiness and GBV Response Plan in Times of Emergency ANALYSIS of MAIN RISKS, VULNERABILITIES and CAPACITY to RESPOND to DISASTER/EMERGENCIES

Readiness and GBV Response Plan in Times of Emergency ANALYSIS OF MAIN RISKS, VULNERABILITIES AND CAPACITY TO RESPOND TO DISASTER/EMERGENCIES The Project: Strengthening Humanitarian Protection System for Women Survivor of Gender Based Violence in North and Middle Gaza AACID 2017/0CC007/2017 Prepared by the team: Abed El-Monem El-Tahrawi Team Leader Osama Albalawi Consultancy team member/ Contact Person Firyal Thabet Consultancy team member Mariam Shaqura Consultancy team member Submitted to: Fundación Alianza por los Derechos, la Igualdad y la Solidaridad Internacional (Alianza) Feb 2020 CONTENTS 1 1. INTRODUCTION 2. METHODOLOGY 2.1 Research and literature review 2.2 Field work 2.3 Validation workshop 2.4 Drills 3. CONTEXT 3.1 Jabalia 3.2 Nuseirat 4. PLANNING IN AN EMERGENCY. RISK ANALYSIS 4.1 Disasters experienced in the last ten years 4.2 Disaster-prone places 4.3 Who are the most exposed to violence? 4.4 Risk analysis of GBV 5. PREPAREDNESS AND RESPONSE IN AN EMERGENCY 5.1 Inter-institutional coordination in emergency time 5.2 Places that shelter displaced internally displaced people 5.3 Past Experiences of Communities in Emergency and aftermath. 5.4 The role of women, men, girls and boys in previous emergencies. 5.5 The current Gaps of the CBOs in Emergency response. 6. PREVENTION AND RESPONSE TO GBV 6.1 Previous experience in emergencies, readiness and ability to deal with GBVS 6.2 Current capacity of CBOs in Emergency Preparedness and Response to GBV 6.3 Measures to mitigate GBV risks. 6.4 Community-based capacity to respond to GBV situations in times of emergency 6.5 The logical framework matrix of the GBV emergency plan 7.