AJ 2016 327-361 Reviews.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

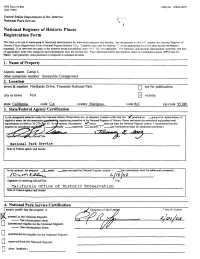

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior » , • National Park Service V National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determination for individual properties and districts Sec instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" lor 'not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and area of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10- 900A). Use typewriter, word processor or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property____________________________________________________ historic name Camp 4 other name/site number Sunnyside Campground__________________________________________ 2. Location_______________________________________________________ street & number Northside Drive, Yosemite National Park |~1 not for publication city or town N/A [_xj vicinity state California code CA county Mariposa code 043 zip code 95389 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this Itjiomination _irquest for determination of eligibility meets the documentationsJand»ds-iJar -

Mountaineering War and Peace at High Altitudes

Mountaineering War and Peace at High Altitudes 2–5 Sackville Street Piccadilly London W1S 3DP +44 (0)20 7439 6151 [email protected] https://sotherans.co.uk Mountaineering 1. ABBOT, Philip Stanley. Addresses at a Memorial Meeting of the Appalachian Mountain Club, October 21, 1896, and other 2. ALPINE SLIDES. A Collection of 72 Black and White Alpine papers. Reprinted from “Appalachia”, [Boston, Mass.], n.d. [1896]. £98 Slides. 1894 - 1901. £750 8vo. Original printed wrappers; pp. [iii], 82; portrait frontispiece, A collection of 72 slides 80 x 80mm, showing Alpine scenes. A 10 other plates; spine with wear, wrappers toned, a good copy. couple with cracks otherwise generally in very good condition. First edition. This is a memorial volume for Abbot, who died on 44 of the slides have no captioning. The remaining are variously Mount Lefroy in August 1896. The booklet prints Charles E. Fay’s captioned with initials, “CY”, “EY”, “LSY” AND “RY”. account of Abbot’s final climb, a biographical note about Abbot Places mentioned include Morteratsch Glacier, Gussfeldt Saddle, by George Herbert Palmer, and then reprints three of Abbot’s Mourain Roseg, Pers Ice Falls, Pontresina. Other comments articles (‘The First Ascent of Mount Hector’, ‘An Ascent of the include “Big lunch party”, “Swiss Glacier Scene No. 10” Weisshorn’, and ‘Three Days on the Zinal Grat’). additionally captioned by hand “Caution needed”. Not in the Alpine Club Library Catalogue 1982, Neate or Perret. The remaining slides show climbing parties in the Alps, including images of lady climbers. A fascinating, thus far unattributed, collection of Alpine climbing. -

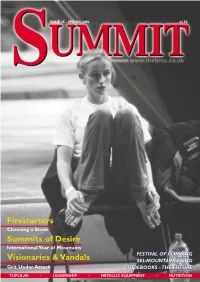

Firestarters Summits of Desire Visionaries & Vandals

31465_Cover 12/2/02 9:59 am Page 2 ISSUE 25 - SPRING 2002 £2.50 Firestarters Choosing a Stove Summits of Desire International Year of Mountains FESTIVAL OF CLIMBING Visionaries & Vandals SKI-MOUNTAINEERING Grit Under Attack GUIDEBOOKS - THE FUTURE TUPLILAK • LEADERSHIP • METALLIC EQUIPMENT • NUTRITION FOREWORD... NEW SUMMITS s the new BMC Chief Officer, writing my first ever Summit Aforeword has been a strangely traumatic experience. After 5 years as BMC Access Officer - suddenly my head is on the block. Do I set out my vision for the future of the BMC or comment on the changing face of British climbing? Do I talk about the threats to the cliff and mountain envi- ronment and the challenges of new access legislation? How about the lessons learnt from foot and mouth disease or September 11th and the recent four fold hike in climbing wall insurance premiums? Big issues I’m sure you’ll agree - but for this edition I going to keep it simple and say a few words about the single most important thing which makes the BMC tick - volunteer involvement. Dave Turnbull - The new BMC Chief Officer Since its establishment in 1944 the BMC has relied heavily on volunteers and today the skills, experience and enthusi- District meetings spearheaded by John Horscroft and team asm that the many 100s of volunteers contribute to climb- are pointing the way forward on this front. These have turned ing and hill walking in the UK is immense. For years, stal- into real social occasions with lively debates on everything warts in the BMC’s guidebook team has churned out quality from bolts to birds, with attendances of up to 60 people guidebooks such as Chatsworth and On Peak Rock and the and lively slideshows to round off the evenings - long may BMC is firmly committed to getting this important Commit- they continue. -

CC J Inners 168Pp.Indd

theclimbers’club Journal 2011 theclimbers’club Journal 2011 Contents ALPS AND THE HIMALAYA THE HOME FRONT Shelter from the Storm. By Dick Turnbull P.10 A Midwinter Night’s Dream. By Geoff Bennett P.90 Pensioner’s Alpine Holiday. By Colin Beechey P.16 Further Certifi cation. By Nick Hinchliffe P.96 Himalayan Extreme for Beginners. By Dave Turnbull P.23 Welsh Fix. By Sarah Clough P.100 No Blends! By Dick Isherwood P.28 One Flew Over the Bilberry Ledge. By Martin Whitaker P.105 Whatever Happened to? By Nick Bullock P.108 A Winter Day at Harrison’s. By Steve Dean P.112 PEOPLE Climbing with Brasher. By George Band P.36 FAR HORIZONS The Dragon of Carnmore. By Dave Atkinson P.42 Climbing With Strangers. By Brian Wilkinson P.48 Trekking in the Simien Mountains. By Rya Tibawi P.120 Climbing Infl uences and Characters. By James McHaffi e P.53 Spitkoppe - an Old Climber’s Dream. By Ian Howell P.128 Joe Brown at Eighty. By John Cleare P.60 Madagascar - an African Yosemite. By Pete O’Donovan P.134 Rock Climbing around St Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai Desert. By Malcolm Phelps P.142 FIRST ASCENTS Summer Shale in Cornwall. By Mick Fowler P.68 OBITUARIES A Desert Nirvana. By Paul Ross P.74 The First Ascent of Vector. By Claude Davies P.78 George Band OBE. 1929 - 2011 P.150 Three Rescues and a Late Dinner. By Tony Moulam P.82 Alan Blackshaw OBE. 1933 - 2011 P.154 Ben Wintringham. 1947 - 2011 P.158 Chris Astill. -

Volume 30 # October 2014

Summit ridge of Rassa Kangri (6250m) THE HIMALAYAN CLUB l E-LETTER l Volume 30 October 2014 CONTENTS Climbs and Explorations Climbs and Exploration in Rassa Glacier ................................................. 2 Nanda Devi East (7434m) Expedition 204 .............................................. 7 First Ascent of P6070 (L5) ....................................................................... 9 Avalanche on Shisha Pangma .................................................................. 9 First Ascent of Gashebrum V (747m) .....................................................0 First Ascent of Payu Peak (6600m) South Pillar ......................................2 Russians Climb Unclimbed 1900m Face of Thamserku .........................3 The Himalayan Club - Pune Section The story of the club’s youngest and a vibrant section. ..........................4 The Himalayan Club – Kolkata Section Commemoration of Birth Centenary of Tenzing Norgay .........................8 The Himalayan Club – Mumbai Section Journey through my Lense - Photo Exhibition by Mr. Deepak Bhimani ................................................9 News & Views The Himalayan Club Hon. Local Secretary in Kathmandu Ms. Elizabeth Hawley has a peak named after her .................................9 Climbing Fees Reduced in India ............................................................. 22 04 New Peaks open for Mountaineering in Nepal ................................ 23 Online Show on Yeti ............................................................................... -

Alpine Club Notes

Alpine Club Notes OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE FOR 1997 PRESIDENT . Sir Christian Bonington CBE VICE PRESIDENTS . J GRHarding LN Griffin HONORARY SECRETARy . DJ Lovatt HONORARY TREASURER . AL Robinson HONORARY LIBRARIAN .. DJ Lovatt HONORARY EDITOR . Mrs J Merz COMMITTEE ELECTIVE MEMBERS E Douglas Col MH Kefford PJ Knott WH O'Connor K Phillips DD Clark-Lowes BJ Murphy WJ Powell DW Walker EXTRA COMMITTEE MEMBERS M JEsten GC Holden OFFICE BEARERS LIBRARIAN EMERITUS '" . R Lawford HONORARY ARCHIVIST . Miss L Gollancz HONORARY KEEPER OF THE CLUB'S PICTURES P Mallalieu HONORARY KEEPER OF THE CLUB'S ARTEFACTS .. R Lawford CHAIRMAN OF THE FINANCE COMMITTEE RFMorgan CHAIRMAN OF THE GUIDEBOOKS EDITORIAL & PRODUCTION BOARD .. LN Griffin CHAIRMAN OF THE HOUSE COMMITTEE .. MH Johnston CHAIRMAN OF THE LIBRARY COUNCIL . GC Band CHAIRMAN OF THE MEMBERSHIP COMMITTEE MWFletcher ASSISTANT EDITORS OF THE Alpine Journal .. JL Bermudez GW Templeman 364 ALPINE CLUB NOTES 365 ASSISTANT HONORARY SECRETARIES: ANNUAL WINTER DINNER MH Johnston BMC LIAISON . P Wickens LECTURES. E Douglas MEETS . PJ Knott MEMBERSHIP . MW Fletcher TRUSTEES ... MF Baker JGR Harding S N Beare HONORARY SOLICITOR .. PG C Sanders AUDITORS AM Dowler Russell New ALPINE CLIMBING GROUP PRESIDENT D Wilkinson HONORARY SECRETARy .. RA Ruddle AC GENERAL AND INFORMAL MEETINGS 1996 16 January General Meeting: Mick Fowler, The North-East Pillar of Taweche 23 January Val d'Aosta evening: Mont Blanc 30 January Informal Meeting: Mike Binnie, Two Years in the Hindu Kush 13 February General Meeting: David Hamilton, -

Les Clochers D'arpette

31 Les Clochers d’Arpette Portrait : large épaule rocheuse, ou tout du moins rocailleuse, de 2814 m à son point culminant. On trouve plusieurs points cotés sur la carte nationale, dont certains sont plus significatifs que d’autres. Quelqu’un a fixé une grande branche à l’avant-sommet est. Nom : en référence aux nombreux gendarmes rocheux recouvrant la montagne sur le Val d’Arpette et faisant penser à des clochers. Le nom provient surtout de deux grosses tours très lisses à 2500 m environ dans le versant sud-est (celui du Val d’Arpette). Dangers : fortes pentes, chutes de pierres et rochers à « varapper » Région : VS (massif du Mont Blanc), district d’Entremont, commune d’Orsières, Combe de Barmay et Val d’Arpette Accès : Martigny Martigny-Combe Les Valettes Champex Arpette Géologie : granites du massif cristallin externe du Mont Blanc Difficulté : il existe plusieurs itinéraires possibles, partant aussi bien d’Arpette que du versant opposé, mais il s’agit à chaque fois d’itinéraires fastidieux et demandant un pied sûr. La voie la plus courte et relativement pas compliquée consiste à remonter les pentes d’éboulis du versant sud-sud-ouest et ensuite de suivre l’arête sud-ouest exposée (cotation officielle : entre F et PD). Histoire : montagne parcourue depuis longtemps, sans doute par des chasseurs. L’arête est fut ouverte officiellement par Paul Beaumont et les guides François Fournier et Joseph Fournier le 04.09.1891. Le versant nord fut descendu à ski par Cédric Arnold et Christophe Darbellay le 13.01.1993. Spécificité : montagne sauvage, bien visible de la région de Fully et de ses environs, et donc offrant un beau panorama sur le district de Martigny, entre autres… 52 32 L’Aiguille d’Orny Portrait : aiguille rocheuse de 3150 m d’altitude, dotée d’aucun symbole, mais équipée d’un relais d’escalade. -

Journal of Alpine Research | Revue De Géographie Alpine

Journal of Alpine Research | Revue de géographie alpine 101-1 | 2013 Lever le voile : les montagnes au masculin-féminin Gender relations in French and British mountaineering The lens of autobiographies of female mountaineers, from d’Angeville (1794-1871) to Destivelle (1960- ) Delphine Moraldo Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rga/2027 DOI: 10.4000/rga.2027 ISSN: 1760-7426 Publisher Association pour la diffusion de la recherche alpine Electronic reference Delphine Moraldo, « Gender relations in French and British mountaineering », Journal of Alpine Research | Revue de géographie alpine [Online], 101-1 | 2013, Online since 03 September 2013, connection on 01 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/rga/2027 ; DOI : 10.4000/rga.2027 This text was automatically generated on 1 May 2019. La Revue de Géographie Alpine est mise à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Gender relations in French and British mountaineering 1 Gender relations in French and British mountaineering The lens of autobiographies of female mountaineers, from d’Angeville (1794-1871) to Destivelle (1960- ) Delphine Moraldo EDITOR'S NOTE Translation: Delphine Moraldo 1 Since alpine clubs first appeared in Europe in the mid 19th century, mountaineering has been one of the most strongly masculinised practices. Not only are mountaineers mostly men, but mountaineering involves manly and heroic social dispositions that establish male domination (Louveau, 2009). 2 Because mountain activities are a feminine-masculine construction, I chose here to look at the practice of mountaineering through the lens of autobiographies of female mountaineers. In these accounts, women never fail to mention male mountaineers, thus giving us an insight into men’s perception of them. -

Alpine Club Notes

Alpine Club Notes OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE FOR 1999 PRESIDENT .. DK Scott CBE VICE PRESIDENTS DrM J Esten P Braithwaite HONORARY SECRETARY.. .. .. GD Hughes HONORARY TREASURER .. .. AL Robinson HONORARY LIBRARIAN .. DJ Lovatt HONORARY EDITOR OF THE ALPINE JOURNAL E Douglas HONORARY GUIDEBOOKS COMMISSIONING EDITOR .. LN Griffin COMMITTEE ELECTIVE MEMBERS .. DD Clark-Lowes JFC Fotheringham JMO'B Gore WJ Powell A Vila DWWalker E RAllen GCHolden B MWragg OFFICE BEARERS LIBRARIAN EMERITUS . RLawford HONORARY ARCHIVIST .. Miss L Gollancz HONORARY KEEPER OF THE CLUB'S PICTURES. P Mallalieu HONORARY KEEPER OF THE CLUB'S ARTEFACTS .. RLawfo;rd HONORARY KEEPER OF THE CLUB'S MONUMENTS. DJ Lovatt CHAIRMAN OF THE FINANCE COMMITTEE .. RFMorgan CHAIRMAN OF THE HOUSE COMMITTEE . MH Johnston CHAIRMAN OF THE LIBRARY COUNCIL GC Band CHAIRMAN OF THE MEMBERSHIP COMMITTEE MWFletcher ASSISTANT EDITORS OF THE Alpine Journal .. JL Bermudez GW Templeman PRODUCTION EDITOR OF THE Alpine Journal Mrs J Merz 347 348 THE ALPINE J OURN AL 1999 AsSISTANT HONORARY SECRETARIES: ANNuAL WINTER DINNER .. MH Johnston BMC LIAISON .. .. GCHolden LECTURES . D 0 Wynne-Jones NORTHERN LECTURE .. E Douglas MEETS . A Vila MEMBERSHIP .. MW Fletcher TRUSTEES . MFBaker JG RHarding S NBeare HONORARY SOLICITOR . PG C Sanders AUDITORS HRLloyd Pannell Kerr Forster ALPINE CLIMBING GROUP PRESIDENT. D Wilkinson HONORARY SECRETARY RA Ruddle GENERAL, INFORMAL, AND CLIMBING MEETINGS 1998 13 January General Meeting: David Hamilton, Pakistan 27 January Informal Meeting: Roger Smith Arolla Alps 10 February -

MONTAGNERE PASSY 9 -10 -11 AOUT 2013 23Ème SALON INTERNATIONAL DU LIVRE DE MONTAGNE Imp

Pascal Tournaire AR CHI TEC TU en MONTAGNERE PASSY 9 -10 -11 AOUT 2013 23ème SALON rnaire INTERNATIONAL DU LIVRE DE MONTAGNE Imp. PLANCHER - Tél. 04 50 97 46 00 Crédit photo : Pascal Tou salonLivrePassyVz.indd 1 En partenariat avec LE JARDIN DES CIMES 09/04/13 07:43 HAUTE-SAVOIE-FRANCE - Tél. / Fax 04 50 58 81 73 - www.salon-livre-montagne.com - [email protected] 1 TRANSACTIONS - LOCATIONS SYNDIC D’IMMEUBLES les contamines immobilier Jean-Marc PEILLEX, MAÎTRE EN DROIT Cl 639 route de Notre Dame de la Gorge 74170 LES CONTAMINES-MONTJOIE Tél. 04 50 47 01 82 - Fax 04 50 47 08 54 [email protected] Retrouvez notre rubrique Librairie-Cartothèque en ligne sur notre site www.auvieuxcampeur.fr Un large choix de guides, topos et cartes ainsi qu’une sélection de livres vous y attendent ! SALLANCHES - 925 route du Fayet - 74700 - Tél. : 04 50 91 26 62 Et aussi à : Lyon - Thonon-Les-Bains - Sallanches - Toulouse-labège - Strasbourg - Albertville - Marseille - Grenoble - Chambéry (Eté 2013) Montagne de Livres… …Livres de Montagne 23ème Salon International du Livre de Montagne de Passy 9 - 10 - 11 août 2013 "ARCHITECTURE EN MONTAGNE" Président d’Honneur Jean-François LYON-CAEN Architecte, Maître-assistant, Responsable du Master et de l’Equipe de recherche « architecture-paysage-montagne » à l’Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Grenoble Achetez votre entrée au Salon du Livre de Montagne directement à l’Offi ce du Tourisme de Passy Contactez le 04 50 58 80 52 Téléphone du salon pour les 3 jours : 06 86 76 69 04 Siège -

ASIAN ALPINE E-NEWS Issue No 75. September 2020

ASIAN ALPINE E-NEWS Issue No 75. September 2020 C CONTENTS All-Afghan Team with two Women Climb Nation's Highest Peak Noshakh 7492m of Afghanistan Page 2 ~ 6 Himalayan Club E-Letter vol. 40 Page 7 ~ 43 1 All-Afghan Team, with 2 Women Climb Nation's Highest – Peak Noshakh 7492m The team members said they did their exercises for the trip in Panjshir, Salang and other places for one month ahead of their journey. Related News • Female 30K Cycling Race Starts in Afghanistan • Afghan Female Cyclist in France Prepares for Olympics Fatima Sultani, an 18-year-old Afghan woman, spoke to TOLOnews and said she and companions reached the summit of Noshakh in the Hindu Kush mountains, which is the highest peak in Afghanistan at 7,492 meters. 1 The group claims to be the first all-Afghan team to reach the summit. Fatima was joined by eight other mountaineers, including two girls and six men, on the 17-day journey. They began the challenging trip almost a month ago from Kabul. Noshakh is located in the Wakhan corridor in the northeastern province of Badakhshan. “Mountaineering is a strong sport, but we can conquer the summit if we are provided the gear,” Sultani said.The team members said they did their exercises for the trip in Panjshir, Salang and other places for one month ahead of their journey. “We made a plan with our friends to conquer Noshakh summit without foreign support as the first Afghan team,” said Ali Akbar Sakhi, head of the team. The mountaineers said their trip posed challenge but they overcame them. -

Australian Mountaineering in the Great Ranges of Asia, 1922–1990

25 An even score Greg Child’s 1983 trip to the Karakoram left him with a chaotic collage of experiences—from the exhilaration of a first ascent of Lobsang Spire to the feeling of hopelessness and depression from losing a friend and climbing partner. It also left his mind filled with strong memories—of people, of events and of mountains. Of the images of mountains that remained sharply focused in Child’s mind, the most enduring perhaps was not that of K2 or its satellite 8000 m peaks. It was of Gasherbrum IV, a strikingly symmetrical trapezoid of rock and ice that presided over Concordia at the head of the Baltoro Glacier (see image 25.1). Though far less familiar than Ama Dablam, Machhapuchhare or the Matterhorn, it is undeniably one of the world’s most beautiful mountains. Child said: After Broad Peak I’d promised myself I would never return to the Himalayas. It was a personal, emphatic, and categoric promise. It was also a promise I could not keep. Again and again the symmetrical silhouette of a truncated, pyramidal mountain kept appearing in my thoughts: Gasherbrum IV. My recollection of it from the summit ridge of Broad Peak, and Pete’s suggestion to some day climb its Northwest Ridge, remained etched in my memory.1 Gasherbrum IV offered a considerable climbing challenge in addition to its beauty. Remarkably, the peak had been climbed only once—in 1958, by its North-East Ridge by Italians Carlo Mauri and Walter Bonatti. There are at least two reasons for its amazing lack of attention.