Wilmington, Delaware and the Deregulation of Consumer Credit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ICHI EVIEW· Volume 6 Number 1 September 1987

...-------Liberty Entails-- Responsibility--------. ICHI EVIEW· Volume 6 Number 1 September 1987 , .' :,' .' .. Welcome Back... I~ And Get Involved! , I September 1987 .3 i I · saauI The University of Michigan TH MICH I GAN PUBLIC SERVICE INTERN R VI W The Student Affairs co TE Magazine of the PROGRAM Washington, D. C. Lansing, MI. University of Michigan From the Edi tor 4 Publisher . Serpent's Tooth 5 David Katz MASS MEETING: r From Suite One: Editorials 6 Associate Publishers Letters to the Edi tor 7 SEPTEMBER 23, 6:00 PM Kurt M. Heyman Mark Powell Review Forum U.s. Policy in Central America, by Dean Baker 8 Editor-in-Chief RACKHAM AUDITORIUM I Seth B. Klukoff 1 Election '88 Executive Editors Choosing the Next President, by Marc Selinger 9 APPLICATION DEADLINE: ocmBER 1 Steve Angelotti Interview: Patricia Schroeder (O-Colo.) 15 Rebecca Chung Interview: Richard Gephardt (O-Mo.) 17 Interview: Pete du Pont (R-Oel.) 18 Campus Affairs Editor Summer internships with Len Greenberger Campus Affairs Personnel Manager A Note to Out-of-Staters: legislative offices, special Marc Selinger What to Expect, by Kurt M. Heyman 20 Women's Issues interest groups, newspaper Staff Taking a Stand, by Rebecca Chung 21 Lisa Babcock, Craig Brown, David Engineering and broadcast media, Calkins, Dan Drumm, Rick Dyer, What's Up on North Campus, by David Vogel Steve George, Asha Gunabalan, 22 executive offices Joseph McCollum, Donna Prince, William Rice, Tracey Stone, Marc Arts and agencies Taxay, Joe Typho, David Vogel Poem: /I A Letter From Us", by David Calkins 23 A Madonnalysis, by Kurt M. -

Volume 6, Issue 3 Fall 2013 , Circa 1839, by Bass Otis

Brandywine Mills, circa 1839, by Bass Otis. Gift of H. Fletcher Brown Volume 6, Issue 3 Fall 2013 6,Issue 3Fall Volume MAKING HISTORY - 2 2013 History Makers Award Dinner Chase Center on the Riverfront Thursday, September 12, 2013 It is with great sadness that the Delaware Historical Society learned of Father Roberto Balducelli’s death on August 9, 2013. The Society is continuing its plans for the History Makers Award Dinner on September 12. It is the hope of the Trustees of the Society that the evening will serve as a tribute to, and The 7th Annual Delaware History celebration of, the life of Father Balducelli as well as honoring Makers Award Dinner on Thursday, the continuing achievements of Dr. Carol E. Hoff ecker and the September 12, 2013, will pay tribute Reverend Canon Lloyd S. Casson. to Delawareans who have truly made a diff erence in the lives of many. The History Makers Award was created in 2007 to recognize living individuals who have from Nazi persecution. He arrived Portrait of an Industrial City: 1830 – made extraordinary and lasting at St. Anthony of Padua Church 1900; Corporate Capital: Wilmington contributions to the quality of life in in 1946 as the fi rst Italian priest in the 20th Century; the classroom Delaware, our nation, and the world. associated with the church. During text, The First State; and Beneath Thy With a 2013 theme of Achievers in his nearly thirty years as pastor of Guiding Hand: A History of Women at a Diverse Delaware, this year the St. Anthony’s, both St. -

Basic Information Biden Was Born on November 20, 1942 (77)

1 ● Basic information12 ○ Biden was born on November 20, 1942 (77), in Scranton, Pennsylvania. ○ In 1953, The Bidens moved to Claymont, Delaware, and then eventually to Wilmington, Delaware. ○ Biden earned his bachelor’s degree in 1965 from the University of Delaware, with a double major in history and political science. ○ Biden graduated from Syracuse University College of Law in 1968 and was admitted to the Delaware bar in 1969. ■ During his first year at Syracuse, Biden was accused of plagiarizing five of fifteen pages of a law review article. As a result, he failed the course and had to retake it. The plagiarism incident has resurfaced during various political campaigns. ● Early political career3 ○ After graduating from law school, Biden began practicing law as a public defender and then for a firm headed by Sid Balick, a locally active Democrat. Biden would go on to officially register as a Democrat at this time. ○ At the end of 1969, Biden ran to represent the 4th district on the New Castle County Council, a usually Republican district. ■ He served on the County Council from 1970 to 1972, while continuing his private law practice. ● 1972 US Senate campaign ○ In 1972, longtime Delaware political figure and Republican incumbent Senator J. Caleb Boggs was considering retirement, which would likely have left US Representative Pete du Pont and Wilmington Mayor Harry G. Haskell Jr. in a divisive primary fight. ■ To avoid that, President Nixon convinced Boggs to run again with full party support which kept several known Democrats out of the race. ○ Biden’s grassroots campaigned, managed by his sister Valerie Biden Owens, focused on withdrawals from Vietnam, the environment, civil rights, mass transit, more equitable taxation, and health care. -

1. Name of Property 3. State/Federal

NPS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM |i D ! ' This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties! and districts. See instructions in l|iow to] Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriatefb.pg oj by entering the information requested, if any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" foi' "rtot applicable." For functtons^afcmeqtural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. PI ice additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name The Delaware Trust Building other names/site number N/A 2. Location street & number 900-912 N. Market Street not for publication _ city or town Wilmington ____________ vicinity _ state Delaware____ code DE county Newcastle____ code 003 zip code 19801 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this \/ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property \S meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant _ nationally _ statewide / locally. -

Coming out of the Gate

Delaware Business Times digital edition brought to you by… Viewpoints: Pete DuPont Foundation, Wilmington Alliance launch E3 initiative 21 June 23, 2020 | Vol. 7 • No. 13 | $2.00 | DelawareBusinessTimes.com Medical tourism company set to hire 200 by end of year 3 DSU on verge of acquiring Wesley College? 5 COMING OUT OF THE GATE Restaurants struggle Delaware businesses seek ways to run to add capacity due to a strong race as state slowly reopens 8-foot distancing rules 7 Sustaining high growth Three of the Delaware companies on the 2019 Inc. 5000 list talk about their pandemic experiences. 23 Spotlight: Two downtown building sales offer hope for market and two large warehouses planned in New Castle To sponsor the Delaware Business Times digital edition, May 26, 2020 | Vol. 7 • No. 11 | $2.00 | DelawareBusinessTimes.com 15, 16 contact: [email protected] A QUESTION Governor: Consumer OF TRUST confi dence key to reopening economy 13 Desperation grows for restaurants, retail as Phase 1 nears 4 Small businesses plead their case to Carney Pandemic reinforces to loosen rules prior to reopening need for downstate broadband 6 Dear Governor Carney State business organizations plea for governor to lighten restrictions 10-13 Viewpoints: Pete DuPont Foundation, Wilmington Alliance launch E3 initiative 21 June 23, 2020 | Vol. 7 • No. 13 | $2.00 | DelawareBusinessTimes.com Medical tourism company set to hire 200 by end of year 3 DSU on verge of acquiring Wesley College? 5 COMING OUT OF THE GATE Restaurants struggle Delaware businesses seek ways to run to add capacity due to a strong race as state slowly reopens 8-foot distancing rules 7 Sustaining high growth Three of the Delaware companies on the 2019 Inc. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS June 4, 1976 Mr

16728 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS June 4, 1976 Mr. ROBERT C. BYRD. Yes. speeded up the work of the Senate, and on Monday, and by early I mean as early Mr. ALLEN. The Senator spoke of pos I am glad the distinguished assistant ma as very shortly after 11 a.m., and that a sible quorum calls and votes on Monday. jority leader is now following that policy. long working day is in prospect for I would like to comment that I feel the [Laughter.] Monday. present system under which we seem to Mr. ROBERT C. BYRD. Well, my dis be operating, of having all quorum calls tinguished friend is overly charitable to RECESS TO MONDAY, JUNE 7, 1976, go live, has speeded up the work of the day in his compliments, but I had sought AT 11 A.M. Senate. There has only been one quorum earlier today to call off that quorum call call today put in by the distinguished as but the distinguished Senator from Ala Mr. ROBERT C. BYRD. Mr. President, sistant majority leader, and I think the bama, noting that in his judgment I un if there be no further business to come Members of the Senate, realizing that doubtedly was seeking to call off the before the Senate, I move, in accordance a quorum call is going to go live, causes quorum call for a very worthy purpose, with the order previously entered, that them to come over to the Senate Cham went ahead to object to the calling off of the Senate stand in recess until the hour ber when a quorum call is called. -

Iiattrhphtpr Mpralb

I iiattrhpHtpr Mpralb Monday, Aug. 15, 1988 Manchester, Conn. — A City of Village Charm 30 Cents N o w ord N o w a y to beat on Bush the heat Bv Andrew J. Davis Manchester Herald The hazy, hot and humid V P pick weather which will continue to grip Connecticut has forced at least 10 people to seek treatment for heat-related illnesses at Man Related atortee on pages 4 and 5 chester Memorial Hospital. Nor theast Utilities Co. said it may bo By Terence Hunt forced to implement selected The Associated Press blackouts if customers do not cut down on electricity. - NEW ORLEANS — George Bush, keeping up the The hot weather, which has suspense about his running mate, said on the baked Central Connecticut with opening day of the Republican Nationai Convention over 90-degree temperatures ev that he has narrowed the list of candidates but has ery day this month but one. forced not picked one. “ I think my choice will be widely 10 people to seek medical atten accepted when I decide on who that choice is,” Bush tion at Manchester Memorial said today. over the weekend, said Am y ‘ T v e not decided,” Bush said during a round of Avery, hospital spokesman. Nine AP photo interviews on morning television shows. Asked if he people were treated and released were leaning one way or another, Bush replied, THE GIPPER'S GAVEL — President Reagan waves Orleans Convention Center. Reagan told the crowd for difficulty breathing, while one "Yes, of course but (toward) some peopie, I’dsay.” was treated for heat exhaustion, to the crowd as he holds a giant gavel over his that America needs the strength and true grit of she said. -

Delaware History Makers Award Dinner Media Advisory

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Jen Wallace at [email protected] or 302-295-2390 June 24, 2015 The Delaware Historical Society’s 2015 Delaware History Makers Award to Recognize The Honorable Michael N. Castle and Noted Civil Rights Attorney Bryan Stevenson Ninth Annual Delaware History Makers Award Dinner to be held on September 15, 2015 Wilmington, DE —The Delaware Historical Society has chosen The Honorable Michael N. Castle and noted civil rights attorney Bryan Stevenson as the 2015 Delaware History Makers Award honorees. The well-respected and long-time Delaware political leader, Michael N. Castle, a native of Wilmington, served as the Governor of Delaware for two terms and as U.S. Congressman for nine terms. Bryan Stevenson, a native of Milton, is the founder and Executive Director of the Equal Justice Initiative and the author of the critically acclaimed New York Times bestseller, Just Mercy. Both honorees exemplify the 2015 Delaware History Makers Award theme of Public Service and Servant Leadership. The award ceremony and dinner will take place on September 15, 2015 at 5:30 pm at the Chase Center on the Riverfront in Wilmington, DE. Since 2007, the History Makers Award has recognized Delawareans who have made significant and lasting contributions to the quality of life in Delaware, our nation, or the world. Past honorees include Ellen Kullman, Fr. Roberto Balducelli, Rev. Canon Lloyd S. Casson, Dr. Carol Hoffecker, Harold “Tubby” Raymond, Ken Burns, former Governor Pete du Pont, Vice President Joe Biden, Toni Young, and Ed and Peggy Woolard. Proceeds from the event support the Delaware Historical Society’s award-winning educational programs that take place year-round throughout the state. -

MNAT Book 10.4.05

durable legacy A History of Morris, Nichols, Arsht & Tunnell Q By Adrian Kinnane Copyright © 2005 Morris, Nichols, Arsht & Tunnell All rights reserved. Printed and Bound in the United States of America by Inland Press contents Foreword I Acknowledgments III Introduction VI Chapter 1 Foundations 2 Chapter 2 “Judge Morris’s Boys” 28 Chapter 3 War Room 54 Chapter 4 New Horizons 82 Long Term Employees 107 Current partners 108 Notes 109 Photo Credits 114 Index 115 FOREWORD This history of Morris, Nichols, Arsht & Tunnell is more than a the firm’s success and merit a share in the pride that we all enjoy. good read, though it is at least that. It also is an opportunity to savor the As you will learn in the following pages, the founding partners special perspective that seventy-five years affords, and to share with you of the firm subscribed to certain basic values and standards that the story of where we came from, who we are and what we stand for. continue today. Morris, Nichols’s commitment to the highest quality From its beginnings in Judge Hugh Morris’s office in 1930, the firm of service requires the highest levels of commitment and talent by its has blossomed to a significant national presence. It has accomplished greatest resource: its people. In turn, attorneys and staff at the firm this while retaining its character as a Delaware firm: collegial, dedicat- have both cultivated and enjoyed the greatest respect for each other. ed to its community and bar, and expertly qualified to serve clients in These values sustain us in our peak efforts as well as in our daily work, local, national and global markets. -

Towbrrd a Revival 01 Prollressivisld

1972. Ripon Society Endorsements RIPON OCTOBER, 1972 Vol. VIII No. 19 ONE DOLLAR TOWBrrd a Revival 01 ProllressivislD by Daniel J Elazar THE RIPON SOCIETY INC is a Republ~can research , • poUcy orgarnzation whose members are young business, academic and professional men and COMT·EMTS women. It has national headquarters in Cambridge, Massachusetts. chapters in thirteen cities, National Associate members throughout the fifty states, and several affiliated groups of subchapter status. The Society is supported by chapter dues, individucil contribu tions and revenues from its publications and contract work. The Society offers the following options for annual contribution: Con tributor $25 or more; Sustainer $100 or more; Founder $1000 or more. Inquiries about membership and ch~er organization should be addressed to the National Executive DIrector. ENDORSEMENTS .............................................................. 3 NAnONAL GOVEllNING BOABD Officers The Ripon Society's Endorsements of GOP Sena ·Howard F. GUlette, Ir., President torial, Congressional and Gubernatorial Candi " 'au! F. Anderson, Cbairm_ of the Bom "Patricia A. Goldman, Chail'maD of the Executive Committee dates. ·Howard L. Reiter, Vice President "Edward W. MUler, Treasurer "Ron Speed, Secretary Boston Pittsburgh "Martha Reardon "Murray Dickman READER SURVEy .............................................................. 20 Martin A. Linsky I ames Groninger Michael W. Chrlstian Bruce Guenther Please return this Reader Survey to help us plan Cambridge Joel P. Greene Seattle the future of the FORUM. "Bob Stewart "Tom Alberg Gus Southworth Dick Dykeman Chicago Mason D. Morisset "Jared Kaplan Gene 1- Armstrong Thomas Russell WashingtolL Detroit "Allce Tetelman "Dennis Gibson Lorry Finkelstein Stephen Selander WilUe Leftwich Mary E. Low Hartford Nicholas Norton At Large at issue "St art H McC h "·Josiah Lee Auspitz Los &~:;eles' onaug y ""Christoper T. -

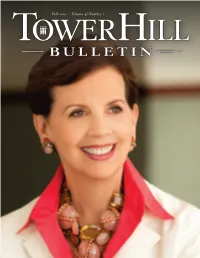

Class Notes 2010 by the Alumni Council, Please Visit Our Web Site At

Update your e-mail address / towerhill.org / Go to Login and My Profile Stay Connected Fall 2010 Class Volume 47.Number Notes 1 2010 Tower Hill Bulletin Fall 2010 1 Aerial view of the Tower Hill School campus in May 2010 after the completion of the renovations of Walter S. Carpenter Field House in the upper left-hand corner. Headmaster Christopher D. Wheeler, Ph.D. in this issue... 2010-2011 Board of Trustees 2...............Headmaster letter David P. Roselle, Board Chair ..............Exceptional Alumni During Extraordinary Times Ellen J. Kullman ’74, Board Vice Chair 3 William H. Daiger, Jr., Board Treasurer 4..............Adrienne Arsht ’60: A Lifetime of Leadership Linda R. Boyden, Board Secretary in Business and Philanthropy Michael A. Acierno Theodore H. Ashford III Dr. Earl J. Ball III 8..............Mike Castle ’57 and Chris Coons ’81: A Delaware Election Robert W. Crowe, Jr. ’90 with National Consequences is a Green-White Contest Ben du Pont ’82 Charles M. Elson W. Whitfield Gardner ’81 10............Morgan Hendry ’01: NASA’s 21st Century Breed of Rocket Scientist Marc L. Greenberg ’81 Thomas D. Harvey 12............Casey Owens ’01: A New Generation Pierre duP. Hayward ’66 Michael P. Kelly ’75 of Americans with a Global Perspective Michelle Shepherd Matthew T. Twyman III ’88 14............Ron “Pathfinder” Strickland ’61: Lance L. Weaver Trail Developer, Dennis Zeleny Chief Advancement Officer Conservationist Julie R. Topkis-Scanlan and Author Editor, Communications Director Nancy B. Schuckert 16............Allison Barlow ’82: Associate Director of Advancement Cultivating a Future for Kim A. Murphy Native American Youth Director of Alumni Programs & Development Office Special Events Kathryn R. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10900 OMB No. 10240018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Downtown Wilmington Commercial Historic District Other names/site number: Name of related multiple property listing: (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: City or town: Wilmington State: DE County: New Castle Not For Publication: Vicinity: ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: ___national ___statewide _ X_ local Applicable National Register Criteria: _X _A ___B _X _C ___D Signature of certifying official/Title: Date ______________________________________________ State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government 1 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service / National Register of Historic Places Registration Form NPS Form 10900 OMB No.