Catholic Identity and Religious Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

God's Creation and Learn More ABET Accredited Schools Including University of Illinois at Urbana- About Him

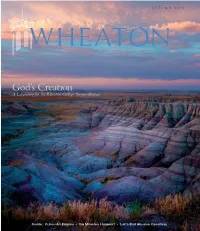

AUTUMN 2013 WHEATON God’s Creation A Laboratory for the Wheaton College Science Station Inside: Cuba––An Enigma • Do Miracles Happen? • Let’s End Abusive Coaching 133858_FC,IFC,01,BC.indd 1 8/4/13 4:31 PM Wheaton College serves Jesus Christ and advances His Kingdom through excellence in liberal arts and graduate programs that educate the whole person to build the church and benefit society worldwide. volume 16 issue 3 A u T umN 2013 6 14 ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS 34 A Word with Alumni 2 Letters From the director of alumni relations 4 News 35 Wheaton Alumni Association News Sports Association news and events 10 56 Authors 40 Alumni Class News Books by Wheaton’s faculty; thoughts on grieving from Luke Veldt ’84. Cover photo: The Badlands of South Dakota is a destination for study and 58 Readings discovery for Wheaton students, and is in close proximity to their base Excerpts from the 2013 commencement address camp, the Wheaton College Science Station (see story, p.6). The geology by Rev. Francis Chan. program’s biannual field camp is a core academic requirement that gives majors experience in field methods as they participate in mapping 60 Faculty Voice exercises based on the local geological features of the Black Hills region. On field trips to the Badlands, environmental science and biology majors Dr. Michael Giuliano, head coach of men’s soccer learn about the arid grassland ecosystem and observe its unique plants and adjunct professor of communication studies, and animals. Geology students learn that the multicolored sediment layers calls for an end to abusive coaching. -

Dialogical Intersections of Tamil and Chinese Ethnic Identity in the Catholic Church of Peninsular Malaysia

ASIATIC, VOLUME 13, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2019 Dialogical Intersections of Tamil and Chinese Ethnic Identity in the Catholic Church of Peninsular Malaysia Shanthini Pillai,1 National University of Malaysia (UKM) Pauline Pooi Yin Leong,2 Sunway University Malaysia Melissa Shamini Perry,3 National University of Malaysia (UKM) Angeline Wong Wei Wei,4 Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR), Malaysia Abstract The contemporary Malaysian Catholic church bears witness to the many bridges that connect ecclesial and ethnic spaces, as liturgical practices and cultural materiality of the Malaysian Catholic community often reflect the dialogic interactions between ethnic diversity and the core of traditional Roman Catholic practices. This essay presents key ethnographic data gathered from fieldwork conducted at selected churches in peninsular Malaysia as part of a research project that aimed to investigate transcultural adaptation in the intersections between Roman Catholic culture and ethnic Chinese and Tamil cultural elements. The discussion presents details of data gathered from churches that were part of the sample and especially reveal how ceremonial practices and material culture in many of these Malaysian Catholic churches revealed a high level of adaptation of ethnic identity and that these in turn are indicative of dialogue and mutual exchange between the repertoire of ethnic cultural customs and Roman Catholic religious practices. Keywords Malaysian Catholic Church, transcultural adaptation, heteroglossic Catholicism, dialogism, ethnic diversity, diaspora 1 Shanthini Pillai (Ph.D.) is Associate Professor at the Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, National University of Malaysia (UKM). She held Research Fellowships at the University of Queensland, Australia and the Asia Research Institute, Singapore, and has published widely in the areas of her expertise. -

Introduction at Last, We Arrive at the Final Teaching Part in Our Series

PAUL M. WILLIAMS [23/12/16] IS ROMAN CATHOLICISM TRUE CHRISTIANITY? – PART 12 THE ECUMENICAL AGENDA Introduction At last, we arrive at the final teaching part in our series looking at the Roman Catholic Church. The fundamental question running throughout this teaching series, the very title of this series has been ‘Is Roman Catholicism True Christianity?’ We began this teaching series by asking a question; ‘are the differences that separate Protestants, Catholics just minor matters of insignificance?’ In the first part of this teaching series we pointed out that if one was to do a Google search to identify the world’s largest religion, one would find that at the top of the list would be Christianity, representing some 2.2 billion people (more than 30% of the world’s population!!). The natural question that arises when being met by such figures is; what type of Christians!! When one looks at the breakdown of these figures, one finds that according to the figures from Pew Research, approximately, 50% of the 2.2 billion Christians are in fact Roman Catholic, with just fewer than 37% comprising of Protestants. Sadly, for many today, the only difference separating these two main Christian groups is one of history and tradition. Indeed, a call goes forth in our day in ever increasing sound, for these Christian groups to unite, after all they will say, don’t we all agree on the fundamentals of the faith!! Sadly, many within Evangelical circles, influential leaders and ministers are regurgitating the same erroneous sentiments!! For those familiar with Church history, for more than a thousand years, Roman Catholicism dominated Western Christianity with its popery and tradition. -

ANNUAL REP RT 1980-81 INSTITUTE of SOU H AST ASIAN STUDIES SINGAPORE I5ER5 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies

ANNUAL REP RT 1980-81 INSTITUTE OF SOU H AST ASIAN STUDIES SINGAPORE I5ER5 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies The Institute of Southeast Asian Studies was established as an autonomous organization in May 1968. It is a regional research centre for scholars and other specialists concerned with modern Southeast Asia . The Institute's research interest is focused on the many-faceted problems of development and modernization, and political and social change in Southea.st Asia . The Institute is governed by a twenty-four-member Board of Trustees on which are represented the National University of Singapore, appointees from the government, as well as representation from a broad range of professional and civic organizations and groups. A ten man Executive Committee oversees day-to-day operations; it is chaired by the Director, the Institute's chief academic and administrative officer. /SEAS at Heng Mui Keng Terrace, Pasir Panjang, Singapore 0511. Professor M1fton Friedman delivering his address at the inaugural Singapore Lecture. 2 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies Annual Report 1 April 1980-31 March 1981 INTRODUCTION growing momentum and range of the Institute's current pro fessional programmes as well as their geographical spread . These The Institute of Southeast Asian Studies is an autonomous developments, together with some of the forthcoming plans of the research centre for scholars and other specialists concerned with Institute, are discussed more fully in the report that follows. modern Southeast Asia, particularly the multifaceted problems of development and modernization, and political and social change. The Institute is supported by annual grants from the Government of BOARD OF TRUSTEES Singapore as well as donations from international and private organizations and individuals. -

Ruah: Revelation to Recognition, Symbol to Reality in the Twenty-First Century Church Georgeann Boras George Fox University

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Doctor of Ministry Seminary 1-1-2013 Ruah: revelation to recognition, symbol to reality in the twenty-first century church Georgeann Boras George Fox University This research is a product of the Doctor of Ministry (DMin) program at George Fox University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Boras, Georgeann, "Ruah: revelation to recognition, symbol to reality in the twenty-first century church" (2013). Doctor of Ministry. Paper 43. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dmin/43 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Seminary at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Ministry by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. GEORGE FOX UNIVERSITY RUAH: REVELATION TO RECOGNITION, SYMBOL TO REALITY IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY CHURCH A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GEORGE FOX EVANGELICAL SEMINARY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MINISTRY BY GEORGEANN BORAS PORTLAND, OREGON MARCH, 2013 George Fox Evangelical Seminary George Fox University Portland, Oregon CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL ________________________________ DMin Dissertation ________________________________ This is to certify that the DMin Dissertation of Georgeann Boras has been approved by the Dissertation Committee on March 13, 2013 for the degree of Doctor of Ministry in Leadership and Spiritual Formation. Dissertation Committee: Primary Advisor: Cecilia Ranger, PhD Secondary Advisor: Kathleen McManus, PhD Copyright © 2013 by Georgeann Boras All rights reserved. The Scripture quotations contained herein are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright © 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A. -

The Spirit-Empowered Discipleship in Acts”

i Liberty University Baptist Theological Seminary “THE SPIRIT-EMPOWERED DISCIPLESHIP IN ACTS” A Thesis Project Submitted to The faculty of Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Ministry By Yan Chai Lynchburg, Virginia May 2015 LIBERTY BAPTIST THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY THESIS PROJECT APPROVAL SHEET B+ ______________________________ GRADE Dr. Frank Schmitt ______________________________ MENTOR Dr. Dwight Rice _____________________________ READER ii Table of Contents CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1 Statement of the Problem 2 Limitations and Delimitations 5 Theoretical Basis for Project 6 Methodology 11 Literature Review 16 Selected Scripture Texts 23 CHAPTER 2 EMPOWERMENT 31 “You shall Receive Power” (Acts 1:8) 33 The Purpose of Empowerment 34 The Necessity for Empowerment 39 Does It Make Any Difference? 46 Greater Works 48 The Signs of Empowerment 49 How Do You Know 51 How to Receive 54 Before and After 58 People Empowerment- Barnabas and Saul 59 Modus Operandi for Discipler in Faith Hope Love 64 CHAPTER 3 EXHORTATION 68 Devoted to Apostles’ Teaching 70 Ethos, Pathos, Logos 73 iii Conviction verses Convenience 81 Information verses Transformation 83 Characteristics of the Apostles’ Preaching 86 Stop Nagging, Start Preaching 86 Preach to Express, not to Impress 86 Preach with a Goal in Mind 88 Preach with Purpose 89 Feed My Lambs, not Giraffes 90 Christ-centered, not Congregation 92 Relevant, not Ranting 94 Practical Training Sessions on Delivering God’s Word 100 Faithfulness in Sowing 100 Faithfulness to God -

MSGH Annual Scientific Meetings and Endoscopy Workshops 16 – 22

Contents MSGH Committee 2013 – 2015 2 GUT 2014 – Organising Committee Message from the President, MSGH & Organising Chairperson, GUT 2014 3 14th MSGH Distinguished Orator 4 – Professor Dr Patrick Kamath 11th Panir Chelvam Memorial Lecturer 5 – Professor Dr John A Windsor Programme At A Glance 6 Daily Programme 7 – 10 Moderators / Chairpersons 11 Faculty Bio-Data 12 – 14 MSGH Annual Scientific Meetings and Endoscopy Workshops 16 – 22 Annual Therapeutic Endoscopy Workshops – “Endoscopy” (16 – 17) Distinguished Endoscopy Lecturers (17) Annual Scientific Meetings – GUT (Overseas Invited Faculty) (18 – 21) MSGH Oration Lecturers / Panir Chelvam Memorial Lecturers (22) Conference Information 23 Function Rooms & Trade Exhibition 24 Acknowledgements 25 Abstracts 26 – 94 Lectures & Symposia (26 – 34) Best Paper Award Presentations (35 – 41) Poster Presentations (42 – 94) pg 1 MSGH Committee 2013 – 2015 President Prof Dr Sanjiv Mahadeva President-Elect Dr Mohd Akhtar Qureshi Immediate Past President Dr Ramesh Gurunathan Hon Secretary Dr Tan Soek Siam Hon Treasurer Assoc Prof Dr Raja Affendi Raja Ali Committee Members Dr Chan Weng Kai Assoc Prof Dr Hamizah Razlan Dr Raman Muthukaruppan Dato’ Dr Tan Huck Joo Dr Tee Hoi Poh Prof Dato’ Dr Goh Khean Lee Prof Dato’ Dr P Kandasami Assoc Prof Dr Raja Affendi Raja Ali GUT 2014 – Organising Committee Organising Chairman Prof Dr Sanjiv Mahadeva Scientific Chairman Dato’ Dr Tan Huck Joo Scientific Co-Chairman Prof Dato’ Dr Goh Khean Lee ECCO Coordinator Assoc Prof Dr Raja Affendi Raja Ali Committee Members Dr Ramesh Gurunathan Dr Mohd Akhtar Qureshi Dr Tan Soek Siam Dr Chan Weng Kai Assoc Prof Dr Hamizah Razlan Dr Raman Muthukaruppan Dr Tee Hoi Poh Prof Dato’ Dr Goh Khean Lee Prof Dato’ Dr P Kandasami pg 2 Message from the President, MSGH & Organising Chairperson, GUT2014 It gives me great pleasure to welcome all delegates and our distinguished faculty to GUT 2014. -

THE CATHOLIC WEEKLY Penang Sarawak Sabah Selangor

Therefore, just as sin came into the world through one man, and death through sin, and so death spread to all men because all sinned — for sin indeed was in the world before the law JUNE 21, 2020 was given, but sin is not counted where there is no law. Yet death reigned from Adam to Moses, TERHAD PP 8460/11/2012(030939) even over those whose sinning was not like the ISSN: 1394-3294 transgression of Adam, who was a type of the Vol. 27 No. 24 THE CATHOLIC WEEKLY one who was to come. Rom. 5:12-14 Non-Muslim houses of worship are open UALA LUMPUR: Non- KPN said activities such as religious pro- Muslim houses of worship cessions, feasts and big gatherings which were difficult to control, were prohibited. Khave been given the green “Committee members of places of wor- light to re-open. ship, religious leaders and devotees are ad- The National Unity Ministry (Kemente- vised to adopt new habits and self-discipline, rian Perpaduan Negara KPN) said the new such as practising social distancing, wearing SOP for religious activities in non-Muslim face masks, washing of hands frequently houses of worship was agreed upon at the with soap, and using hand sanitisers,” the Special Ministerial Meeting regarding the statement said. implementation of the Movement Control Senior Minister (Security Cluster) Datuk Order June 15. Seri Ismail Sabri Yaakob, who is also the “The SOP is in accordance with the guide- Defence Minister, said at a press conference lines provided by the National Security that at the Special Ministerial Meeting on the Council and the Health Ministry,” the KPN implementation of the MCO it was agreed said in a statement on June 15. -

CHOIRS (Youth Choir,RECHOSO,YPC, St.Cecilia, 6.30Am Mass on Wed

PARISH OF OUR MOTHER OF PERPETUAL HELP (Food for thought) R e d e m p t o r i s t C o m m u n i t y Gospel: Matthew 15: 21-28 Rev Fr Joseph Stephen,C.Ss.R. (Parish Priest) Rev Fr Paul Michael Kee, C.Ss.R (Assistant Parish Priest) “It ‘s all about relationship” Address: 19-21, Jalan La Salle, Ipoh Garden, Ipoh, Perak. website: www.omphip.org Telephone Nos.: (Office - 5458 220) (Fax: 5468 495) ANNOUNCEMENTS: In today's Gospel, a Canaanite woman comes to Jesus and cries “TILAPIA” Fish Lovers - SUNDAY SCHOOL NEWS out for His help. But the disciples press Him to "get rid of her." YOUTH FORMATION # 6 for Dear Parishioners On Sunday, 20/8/2017, there will be a What they meant, of course, was "She is not one of us. She is a Primary & Secondary catechism children Gentile woman. Your mission is to us, not to outsiders." will take place on fund raising for the Orang Asli ministry (date) Sunday 20 August, 2017 in our church grounds. They will be (time) 10am to 12 noon. selling their “Tilapia” fish from 8am till Jesus was looking for faith and trust among the people of His 12 noon. All proceeds will go towards own community, and found greater faith within an outsider. He AREA COORDINATORS MEETING Kampung Sekom Orang Asli Educational knew that what He was asking was not easy. He knew the brought forward to Thursday, 24 August, fund. All the fish will be cleaned, packed ramifications of living out the Gospel message, the 2017 @ 8pm and priced according to weight. -

December 2018

THE CATHOLIC MIRROR Vol. 52, No. 12 December 21, 2018 Bishops of Congratulations, Father Ryan Andrew Iowa voice Des Moines native was ordained a priest on Dec. 14 concerns about gun laws By Kelly Mescher Collins Staff Writer In the wake of legisla- tion being introduced in the state, the Iowa Catholic Conference, is voicing concerns. A proposed state Consti- tutional amendment, House Joint Resolution 2009, would subject restrictions on the right of the people to keep and bear arms to “strict scrutiny.” The Iowa Catholic Con- ference opposes the bill because it would make regulating any fire- arms difficult. It could also put current state law regarding back- ground checks and permitting at risk, said Tom Chapman, execu- tive director of the Iowa Catholic Conference. In a December letter to legislators and the general public, signed by the four bishops of Iowa – Archbishop Michael Jackels of the Archdiocese of Dubuque; Bishop Richard Pates of the Di- ocese of Des Moines; Bishop Thomas Zinkula of the Diocese of Davenport; and Bishop Walker Nickless of the Diocese of Sioux Photo by Ken Seeber City – they expressed their con- cerns. “We believe that weap- ons increasingly capable of in- flicting great suffering in a short period of time are simply too accessible,” the letter said. “The right to bear arms as found in our Constitution must be balanced against the safety and well-being of the populace as a whole. The Supreme Court has held that such restrictions are fully compatible Photos by Anne Marie Cox with the Second Amendment.” A standing-room-only crowd filled St. -

Ministry Focus Paper Approval Sheet

Ministry Focus Paper Approval Sheet This ministry focus paper entitled A STRATEGY FOR STARTING MISSIONAL COMMUNITIES IN SINGAPORE THROUGH BIVOCATIONAL MINISTRY Written by KIERAN KIAN HOCK CHEW and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Ministry has been accepted by the Faculty of Fuller Theological Seminary upon the recommendation of the undersigned readers: _____________________________________ Paul Pierson _____________________________________ Kurt Fredrickson Date Received: July 19, 2019 A STRATEGY FOR STARTING MISSIONAL COMMUNITIES IN SINGAPORE THROUGH BIVOCATIONAL MINISTRY A MINISTRY FOCUS PAPER SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY FULLER THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF MINISTRY BY KIERAN KIAN HOCK CHEW MAY 2019 Copyright© 2019 by Kieran Chew All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT A Strategy for Starting Missional Communities in Singapore through Bivocational Ministry Kieran Kian Hock Chew Doctor of Ministry School of Theology, Fuller Theological Seminary 2019 The purpose of this project is to develop a strategy for starting missional communities in Singapore through the work of bivocational personnel. To achieve this, a new work was started with the intention of reaching non-Christians, bringing them into community and discipleship, developing them as leaders and empowering and releasing them to form new missional communities. Special attention was made on spiritual formation, community life together and a transformative leadership process of developing leaders who replicate themselves. The context of Singapore is one in which Christianity has enjoyed great success. Singapore churches generally embrace a missiological theology but this outlook is being eroded as churches grow and are becoming institutionalized. -

St. Thomas' Seminary Given Accreditation

Member of Audit Bureau of Circulations Contents Copyright by the Catholic Press Society, Inc., 1961 — Permission to Reproduce, Except On Articles Otherwise Marked, Given After 12 M. Friday Following Issue 3fL Jhi}^ dhdM JU isjdjjayt, 0 ^ A a i a L, d l M i i u t , ^/^tsiL dim vutL a n d . £aM k /RstjoksL, d ild biicL .^ ^ y^ y^ ^ DENVERCATHOUC Holy Week Schedule A schedule of,the Holy Week REGISTER s e ^ c e s in p u sh es of the Easter Message ar^diocese starts on page 19. THURSDAY, MARCH DENVER, COLORADO of Archbishop Vehr 'T H E RESURRECTION of Jesus Christ is the resplen- St. Thomas' Seminary ■“■ dence of His Divinity, the proof unshaken of His ' devastating victory over sin and death. On the Cross the Sovior repaired, by action infinite, the morol evil bom. in Eden and nurtured in succeeding ages. Glorious Easter morn is the manifestation of that reparation, the Given Accreditation unfurlirig of the flag of Jesus' triumph over the un holy forces. College Courses Recognized | T IS THE PRAYER of Holy Mother Church in this St. Thomas’ Seminary, which educates students for socred season that all men might come to a deep the priesthood in the Archdiocese of.Denver, has re rwlization of the significance of Christ's arising from ce iv e notice that the seminary college has been accred the bed of deoth. It is the ardent desire of the Holy ited by the North Central AMOciation of Colleges and Father, Pope John XXIII, thot all men, the universe Secondary'Schools, the Very Reti.