'Hate Speech' and Incitement to Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arrow Cross Women and Female Informants Andrea Petö

Arrow Cross Women and Female Informants Andrea Petö To cite this version: Andrea Petö. Arrow Cross Women and Female Informants. Baltic Worlds, 2009, pp.49-52. hal- 03226368 HAL Id: hal-03226368 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03226368 Submitted on 22 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 48 essay feature interview reviews 49 “The Arrow Cross did not bother with cal climate hardened due to the Cold War, new legisla- of the role of law. Women were encouraged to study women. Women were not partners for tion was introduced in order to regulate the function law because they were seen as reliable. They began to them. During the interrogations, I did not of people’s tribunals more strictly. Act VII of 1946 was graduate from the university and receive important meet a single Arrow Cross woman. And you followed by Act XXXIV of 1947, which regulated the positions in the newly transformed state apparatus. are saying this only now [that 10 percent of proceedings.1 Arrow Cross party members were women]. Critics of the work of the People’s Tribunals in Hun- ARROW CROSS Why didn’t you tell me this thirty-five years gary have used both legal and political arguments to WOMEN ActIVISTS ago, when I could have swooped down on define the tribunals’ shortcomings.2 The legal critique According to membership records, estimated 15,000 them?” focuses on these courts’ failure to function in a “legal” women were members of the Arrow Cross Party in manner. -

1 Introduction

1Introduction In 2003 Iheld apubliclecture in Budapest on the history of the Arrow Cross women’smovement.Atthe end of the lecture an elderlygrey-haired man ap- proached me with aquestion: “Have youheard about PiroskaDely?”“Of course – Ianswered self-assuredly –,the literatureonthe people’stribunals mention her name. She was the bloodthirsty Arrow Cross woman who was executed after her people’stribunal trial.” My colleagues in Hungary never exhibited much enthusiasm when Itold them about my research on women in the Arrow Cross Party.¹ Still, everyone knew Dely’sname, because every volume on post-Second World Warjusticelisted the namesofthosefemalewar crimi- nals, among them Piroska Dely, who weresentenced to death and executed.² The elderlyman with impeccable silverhair nodded and said: “Imet her.” This is how Imet agroup of the Csengery Street massacre’ssurvivors who for decades fought for adignified remembrance of the bloodyevents. János Kun’s sentencegaveanentirelynew dimension to my research, which led to my Hun- garian AcademyofSciences doctoral dissertation and to the writing of this book. Ithank them for helping in my researchand Idedicate this book to them. During the Second World WarHungary was Germany’sloyal foreign ally. From 1938 four Anti-Jewish Laws were put in effect,that is laws that limited the employment,marriage, and property rights of JewishHungarian citizens. On April 11, 1941Hungary’sarmed forces participated in the German invasion of Yugoslavia with the aim of returning territories lost at the end of the First World War. Forthese territorial gains Hungary paid ahugeprice: the Hungarian economywas sacrificed to Germany’swar goals. In the meantime, Hungarian propaganda machinery emphasized the Hungarian government’sindependence and its nationalcommitment,but the country’sterritorial demands and geopol- itical realities tied Hungary to Nazi Germany,while Germanyincreasinglyexpect- ed commitment and support from its allies. -

Jewish Survival in Budapest, March 1944 – February 1945

DECISIONS AMID CHAOS: JEWISH SURVIVAL IN BUDAPEST, MARCH 1944 – FEBRUARY 1945 Allison Somogyi A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2014 Approved by: Christopher Browning Chad Bryant Konrad Jarausch © 2014 Allison Somogyi ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Allison Somogyi: Decisions amid Chaos: Jewish Survival in Budapest, March 1944 – February 1945 (Under the direction of Chad Bryant) “The Jews of Budapest are completely apathetic and do virtually nothing to save themselves,” Raoul Wallenberg stated bluntly in a dispatch written in July 1944. This simply was not the case. In fact, Jewish survival in World War II Budapest is a story of agency. A combination of knowledge, flexibility, and leverage, facilitated by the chaotic violence that characterized Budapest under Nazi occupation, helped to create an atmosphere in which survival tactics were common and widespread. This unique opportunity for agency helps to explain why approximately 58 percent of Budapest’s 200,000 Jews survived the war while the total survival rate for Hungarian Jews was only 26 percent. Although unique, the experience of Jews within Budapest’s city limits is not atypical and suggests that, when fortuitous circumstances provided opportunities for resistance, European Jews made informed decisions and employed everyday survival tactics that often made the difference between life and death. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank everybody who helped me and supported me while writing and researching this thesis. First and foremost I must acknowledge the immense support, guidance, advice, and feedback given to me by my advisor, Dr. -

Open Final Thesis Draft__Jacob Green.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Resurgent Antisemitism: The Threat of Viktor Orban and His Political Arsenal JACOB GREEN SPRING 2021 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in History and Spanish with honors in History Reviewed and approved* by the following: Tobias Brinkmann Malvin and Lea Bank Associate Professor of Jewish Studies and History Thesis Supervisor Cathleen Cahill Associate Professor of History Honors Advisor * Electronic approvals are on file. i ABSTRACT This thesis will analyze the role and prevalence of antisemitism in Hungary across various time periods to better understand the populist foundation of the modern crisis. Prime Minister Viktor Orban and his Fidesz government rely on antisemitic tropes to maintain political power and realize their authoritarian vision for the nation. By investigating Hungarian history from World War I through the communist era, this thesis will develop a historical framework to better understand recent events and why they are so troubling. Next, the modern context will be examined to uncover Orban’s tactical use of antisemitism and historical revisionism. Orban’s tactics leave minority communities in Hungary, especially the nation’s large Jewish community, vulnerable to nationalist outbursts and undermine democracy. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ..................................................................................................... iii LIST OF TABLES ...................................................................................................... -

THE IDEOLOGY of ILLIBERALISM in the PROFESSIONS: LEFTIST and RIGHTIST RADICALISM AMONG HUNGARIAN DOCTORS, LAWYERS, and ENGINEERS, 1918-45 M'ria M

• THE IDEOLOGY OF ILLIBERALISM IN THE PROFESSIONS: LEFTIST AND RIGHTIST RADICALISM AMONG HUNGARIAN DOCTORS, LAWYERS, AND ENGINEERS, 1918-45 M'ria M. Kovacs In the period between the two world wars, Hungary's professions were transformed from a politically liberal and professionally oriented elite into an illiberal pressure group attracted to radical politics. This metamorphosis of the professions contradicted the expectations of many analysts of modernization from Emile Durkheim to Talcott Parsons and T.H. Marshall who viewed the professions as the most secure element of Western liberal culture. In Parson's view in particular, the professions constituted the strongest allies of the modern liberal state: they were immune to both the anti-modernistic cultural despair and the political conservatism of more traditional elites.1 . The professional elites of Eastern and Central Europe defied this kind of sociological optimism. They increasingly turned from being allies of the liberal state into the partners of illiberal movements and governments. Already in the 1930s, this transformat;ion gave birth to a new, more pessimistic school of thought on the professions. Despite their very different political persuasions, advocates of this pessimistic view, such as Friedrich Hayek or Michael Polanyi, anticipated the closing of open society by technocrats and painted a picture of a new despotism led by what Bertrand Russell called the "oligarchies of opinion."2 Educated elites were no longer portrayed as . symbols of liberalism or stability, let alone democracy, but rather as a new threat to freedom and political democracy. Interwar developments in Central and Eastern Europe gave ~ more justification to the pessimists than to optimists such as Parsons. -

Gendered Exclusions and Inclusions in Hungary's Right-Radical Arrow Cross Party (1939-1945): a Case Study of Three Female Party Members Pető, Andrea

www.ssoar.info Gendered Exclusions and Inclusions in Hungary's Right-Radical Arrow Cross Party (1939-1945): A Case Study of Three Female Party Members Pető, Andrea Preprint / Preprint Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Pető, A. (2014). Gendered Exclusions and Inclusions in Hungary's Right-Radical Arrow Cross Party (1939-1945): A Case Study of Three Female Party Members. Hungarian Studies Review, 41(1-2), 107-130. https://nbn-resolving.org/ urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-72972-5 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY Lizenz (Namensnennung) zur This document is made available under a CC BY Licence Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden (Attribution). For more Information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de Hungarian Studies Review, Vol. XLI, Nos, 1-2 (2014) Gendered Exclusions and Inclusions in Hungary’s Right-Radical Arrow Cross Party (1939-1945): A Case Study of Three Female Party Members Andrea Peto World War IIis not exactly known as a time when many women broke through the glass ceiling to become visible in public life.1 In interwar Hungary political citizenship was determined by growing restrictions on women’s suffrage. These restrictions were opposed by social democrats and communists, but also by the increasingly powerful far right.2 In this paper I look at four women on the far right who managed to break through the glass ceiling. In doing so, I seek to determine how they represented the far right’s image of women.3 How was political citizenship defined by the far right and how did the individual women involved in politics fit this definition? Who were the women on the extreme right and what can we learn from their life stories? These questions are poignant if our aim is to analyze female mobilization on the far right in terms of women’s agency. -

State of Florida Resource Manual on Holocaust Education Grades

State of Florida Resource Manual on Holocaust Education Grades 7-8 A Study in Character Education A project of the Commissioner’s Task Force on Holocaust Education Authorization for reproduction is hereby granted to the state system of public education. No authorization is granted for distribution or reproduction outside the state system of public education without prior approval in writing. The views of this document do not necessarily represent those of the Florida Department of Education. 2 Table of Contents Introduction Definition of the Term Holocaust ............................................................ 7 Why Teach about the Holocaust............................................................. 8 The Question of Rationale.............................................................. 8 Florida’s Legislature/DOE Required Instruction.............................. 9 Required Instruction 1003.42, F.S.................................................. 9 Developing a Holocaust Unit .................................................................. 9 Interdisciplinary and Integrated Units ..................................................... 11 Suggested Topic Areas for a Course of Study on the Holocaust............ 11 Suggested Learning Activities ................................................................ 12 Eyewitnesses in Your Classroom ........................................................... 12 Discussion Points/Questions for Survivors ............................................. 13 Commonly Asked Questions by Students -

Robert O. Paxton-The Anatomy of Fascism -Knopf

Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page b also by robert o. paxton French Peasant Fascism Europe in the Twentieth Century Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order, 1940–1944 Parades and Politics at Vichy Vichy France and the Jews (with Michael R. Marrus) Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page i THE ANATOMY OF FASCISM Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page ii Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page iii THE ANATOMY OF FASCISM ROBERT O. PAXTON Alfred A. Knopf New York 2004 Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page iv this is a borzoi book published by alfred a. knopf Copyright © 2004 by Robert O. Paxton All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Distributed by Random House, Inc., New York. www.aaknopf.com Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc. isbn: 1-4000-4094-9 lc: 2004100489 Manufactured in the United States of America First Edition Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page v To Sarah Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page vi Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page vii contents Preface xi chapter 1 Introduction 3 The Invention of Fascism 3 Images of Fascism 9 Strategies 15 Where Do We Go from Here? 20 chapter 2 Creating Fascist Movements 24 The Immediate Background 28 Intellectual, Cultural, and Emotional -

Hungary and the Holocaust Confrontation with the Past

UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES Hungary and the Holocaust Confrontation with the Past Symposium Proceedings W A S H I N G T O N , D. C. Hungary and the Holocaust Confrontation with the Past Symposium Proceedings CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM 2001 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council or of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Third printing, March 2004 Copyright © 2001 by Rabbi Laszlo Berkowits, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Randolph L. Braham, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Tim Cole, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by István Deák, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Eva Hevesi Ehrlich, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Charles Fenyvesi; Copyright © 2001 by Paul Hanebrink, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Albert Lichtmann, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by George S. Pick, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum In Charles Fenyvesi's contribution “The World that Was Lost,” four stanzas from Czeslaw Milosz's poem “Dedication” are reprinted with the permission of the author. Contents -

We Were There. a Collection of Firsthand Testimonies

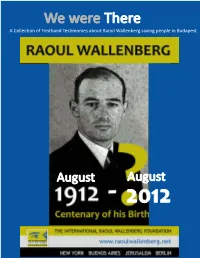

We were There A Collection of Firsthand Testimonies about Raoul Wallenberg saving people in Budapest August August 2012 We Were There A Collection of Firsthand Testimonies About Raoul Wallenberg Saving People in Budapest 1 Contributors Editors Andrea Cukier, Daniela Bajar and Denise Carlin Proofreader Benjamin Bloch Graphic Design Helena Muller ©2012. The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation (IRWF) Copyright disclaimer: Copyright for the individual testimonies belongs exclusively to each individual writer. The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation (IRWF) claims no copyright to any of the individual works presented in this E-Book. Acknowledgments We would like to thank all the people who submitted their work for consideration for inclusion in this book. A special thanks to Denise Carlin and Benjamin Bloch for their hard work with proofreading, editing and fact-checking. 2 Index Introduction_____________________________________4 Testimonies Judit Brody______________________________________6 Steven Erdos____________________________________10 George Farkas___________________________________11 Erwin Forrester__________________________________12 Paula and Erno Friedman__________________________14 Ivan Z. Gabor____________________________________15 Eliezer Grinwald_________________________________18 Tomas Kertesz___________________________________19 Erwin Koranyi____________________________________20 Ladislao Ladanyi__________________________________22 Lucia Laragione__________________________________24 Julio Milko______________________________________27 -

Volume 110, Issue 2 (The Sentinel, 1911

April 14, 1938 THE SENTINEL 51 Canadian and American Pioneers Killed Hungary Launches Anti-Semitic Program In Ambush by Band of Arab Terrorists Jerusalem, Apr. 11 (WNS-Palcor cordon arrived soon thereafter. After As Premier Proposes Restricting Bills Agency)-Two pioneers who had come exchanging signals with the Mishmar to Palestine from the United States Haemek settlers, in the hope of head- Plan Legislation to Curb Participation and Canada were shot to death as they ing off the escaping band, the airplane were returning from ploughing in the pilot scouted around for hours in a In Professional, Commercial fields toward the colony of Juara, re- fruitless search. Armored 'cars were cently named "Ain Hashophet" in pressed into service, as troops and and Industrial Fields honor of Supreme Court Justice Louis police spread fanwise throughout the D. Brandeis. The latest victims of Jezreel area to apprehend the band Budapest, Apr. 11 (WNS)-Hungary which only 20% of the members may Arab terrorism were Eliezer Krongold, which mowed down the young settlers officially embarked on a program of be Jews; 2-limits to 20% the amount 24, and Ephriam Tiktin, 21. They were without giving them a chance for de- anti-Semitism when Premier Koloman of wages and salaries that may be paid with two other settlers who were riding fense. By foot, by cart and truck Daranyi laid before the lower house of to Jews by any business or banking in two carts when a band of thirty hundreds 'of settlers in the Valley of Parliament a sweeping anti-Jewish enterprise and forbids any such en- men encircled their vehicles and Jezreel streamed toward Ain Hasho- omnibus bill which will limit drastical- terprise to employ more than 20% pumped a stream of lead into them as phet for the funeral exercises for ly Jewish participation in Hungary's Jews; 3-new Jewish admissions to the they came near the Arab village of Eliezer Krongold and Tiktin. -

Nazi Party from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Create account Log in Article Talk Read View source View history Nazi Party From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This article is about the German Nazi Party that existed from 1920–1945. For the ideology, see Nazism. For other Nazi Parties, see Nazi Navigation Party (disambiguation). Main page The National Socialist German Workers' Party (German: Contents National Socialist German Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (help·info), abbreviated NSDAP), commonly known Featured content Workers' Party in English as the Nazi Party, was a political party in Germany between 1920 and 1945. Its Current events Nationalsozialistische Deutsche predecessor, the German Workers' Party (DAP), existed from 1919 to 1920. The term Nazi is Random article Arbeiterpartei German and stems from Nationalsozialist,[6] due to the pronunciation of Latin -tion- as -tsion- in Donate to Wikipedia German (rather than -shon- as it is in English), with German Z being pronounced as 'ts'. Interaction Help About Wikipedia Community portal Recent changes Leader Karl Harrer Contact page 1919–1920 Anton Drexler 1920–1921 Toolbox Adolf Hitler What links here 1921–1945 Related changes Martin Bormann 1945 Upload file Special pages Founded 1920 Permanent link Dissolved 1945 Page information Preceded by German Workers' Party (DAP) Data item Succeeded by None (banned) Cite this page Ideologies continued with neo-Nazism Print/export Headquarters Munich, Germany[1] Newspaper Völkischer Beobachter Create a book Youth wing Hitler Youth Download as PDF Paramilitary Sturmabteilung