The New England Narrative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study Guide for the Georgia History Exemption Exam Below Are 99 Entries in the New Georgia Encyclopedia (Available At

Study guide for the Georgia History exemption exam Below are 99 entries in the New Georgia Encyclopedia (available at www.georgiaencyclopedia.org. Students who become familiar with these entries should be able to pass the Georgia history exam: 1. Georgia History: Overview 2. Mississippian Period: Overview 3. Hernando de Soto in Georgia 4. Spanish Missions 5. James Oglethorpe (1696-1785) 6. Yamacraw Indians 7. Malcontents 8. Tomochichi (ca. 1644-1739) 9. Royal Georgia, 1752-1776 10. Battle of Bloody Marsh 11. James Wright (1716-1785) 12. Salzburgers 13. Rice 14. Revolutionary War in Georgia 15. Button Gwinnett (1735-1777) 16. Lachlan McIntosh (1727-1806) 17. Mary Musgrove (ca. 1700-ca. 1763) 18. Yazoo Land Fraud 19. Major Ridge (ca. 1771-1839) 20. Eli Whitney in Georgia 21. Nancy Hart (ca. 1735-1830) 22. Slavery in Revolutionary Georgia 23. War of 1812 and Georgia 24. Cherokee Removal 25. Gold Rush 26. Cotton 27. William Harris Crawford (1772-1834) 28. John Ross (1790-1866) 29. Wilson Lumpkin (1783-1870) 30. Sequoyah (ca. 1770-ca. 1840) 31. Howell Cobb (1815-1868) 32. Robert Toombs (1810-1885) 33. Alexander Stephens (1812-1883) 34. Crawford Long (1815-1878) 35. William and Ellen Craft (1824-1900; 1826-1891) 36. Mark Anthony Cooper (1800-1885) 37. Roswell King (1765-1844) 38. Land Lottery System 39. Cherokee Removal 40. Worcester v. Georgia (1832) 41. Georgia in 1860 42. Georgia and the Sectional Crisis 43. Battle of Kennesaw Mountain 44. Sherman's March to the Sea 45. Deportation of Roswell Mill Women 46. Atlanta Campaign 47. Unionists 48. Joseph E. -

Arizona SAR Hosts First Grave Marking FALL 2018 Vol

FALL 2018 Vol. 113, No. 2 Q Orange County Bound for Congress 2019 Q Spain and the American Revolution Q Battle of Alamance Q James Tilton: 1st U.S. Army Surgeon General Arizona SAR Hosts First Grave Marking FALL 2018 Vol. 113, No. 2 24 Above, the Gen. David Humphreys Chapter of the Connecticut Society participated in the 67th annual Fourth of July Ceremony at Grove Street Cemetery in New Haven, 20 Connecticut; left, the Tilton Mansion, now the University and Whist Club. 8 2019 SAR Congress Convenes 13 Solid Light Reception 20 Delaware’s Dr. James Tilton in Costa Mesa, California The Prison Ship Martyrs Memorial Membership 22 Arizona’a First Grave Marking 14 9 State Society & Chapter News SAR Travels to Scotland 24 10 2018 SAR Annual Conference 16 on the American Revolution 38 In Our Memory/New Members 18 250th Series: The Battle 12 Tomb of the Unknown Soldier of Alamance 46 When You Are Traveling THE SAR MAGAZINE (ISSN 0161-0511) is published quarterly (February, May, August, November) and copyrighted by the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. Periodicals postage paid at Louisville, KY and additional mailing offices. Membership dues include The SAR Magazine. Subscription rate $10 for four consecutive issues. Single copies $3 with checks payable to “Treasurer General, NSSAR” mailed to the HQ in Louisville. Products and services advertised do not carry NSSAR endorsement. The National Society reserves the right to reject content of any copy. Send all news matter to Editor; send the following to NSSAR Headquarters: address changes, election of officers, new members, member deaths. -

The Indian Trade War Reconsidered: Morris on Ivers

Larry E. Ivers. This Torrent of Indians: War on the Southern Frontier, 1715-1728. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2016. 292 pp. $24.95, paper, ISBN 978-1-61117-606-3. Reviewed by Michael Morris Published on H-SC (September, 2016) Commissioned by David W. Dangerfield (University of South Carolina - Salkehatchie) If South Carolina’s Yamasee War is ever given tribes and forgotten forts. His secondary works a subtitle, it could rightly be called the Great Indi‐ run the gamut from Verner Crane's 1959 classic, an Trade War. Larry Ivers, a lawyer by training The Southern Frontier to William Ramsey's 2008 with a military background, notes in his preface work, The Yamasee War. that his intent was to fll a void in the history of The frst three chapters set the stage for con‐ the Yamasee War and to provide a more detailed flict by discussing the Indian agents and traders analysis of the military operations of the war. To who caused the crisis by enslavement of debtor that end, he clearly succeeds in recreating the sto‐ Indians, and one of its strengths is naming people ry of a colony at war aggravated by professional who are otherwise shadowy fgures in backcoun‐ Indian traders who trafficked in Indian slaves to try history. The Yamasee leadership clearly pay their debts. Ivers reveals an incredibly de‐ warned traders Samuel Warner and William Bray tailed account of the debacle and this detailed of a planned murder of all traders and an attack analysis is both a major strength and a minor on the colony if the South Carolina government weakness of the work. -

A Study of an Eighteenth-Century Yamasee Mission Community in Colonial St Augustine Andrea Paige White College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2002 Living on the Periphery: A Study of an Eighteenth-Century Yamasee Mission Community in Colonial St Augustine andrea Paige White College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation White, andrea Paige, "Living on the Periphery: A Study of an Eighteenth-Century Yamasee Mission Community in Colonial St Augustine" (2002). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626354. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-whwd-r651 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIVING ON THE PERIPHERY: A STUDY OF AN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY YAMASEE MISSION COMMUNITY IN COLONIAL ST. AUGUSTINE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Anthropology The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Andrea P. White 2002 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree of aster of Arts Author Approved, November 2002 n / i i WJ m Norman Barka Carl Halbirt City Archaeologist, St. Augustine, FL Theodore Reinhart TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vi LIST OF TABLES viii LIST OF FIGURES ix ABSTRACT xi CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 2 Creolization Models in Historical Archaeology 4 Previous Archaeological Work on the Yamasee and Significance of La Punta 7 PROJECT METHODS 10 Historical Sources 10 Research Design and The City of St. -

AP US History Opportunity and Oppression in Colonial Society 1

AP US History Opportunity and Oppression in Colonial Society 1. The system of indentured labor used during the Colonial period had which of the following effects? A. It enabled England to deport most criminals. B. It enabled poor people to seek opportunity in America. C. It delayed the establishment of slavery in the South until about 1750. D. It facilitated the cultivation of cotton in the South. E. It instituted social equality. 2. Indentured servants were usually A. slaves who had been emancipated by their masters B. free blacks forced to sell themselves into slavery by economic conditions. C. paroled prisoners bound to a lifetime of service in the colonies D. persons who voluntarily bound themselves to labor for a set number of years in return for transportation in the colonies. E. the sons and daughters of slaves. 3. The headright system adopted in the Virginia colony A. determined the eligibility of a settler for voting and holding office. B. toughened the laws applying to indentured servants. C. gave 50 acres of land to anyone who would transport himself to the colony. D. encouraged the development of urban centers. E. prohibited the settlement of single men and women in the colony. 4. Of the African slaves brought to the New World by Europeans from 1492 through 1770, the vast majority were shipped to A Virginia B the Carolinas C the Caribbean D Georgia E Florida 5. A majority of the early English migrants to the Chesapeake were A. Families with young children B. Indentured servants C. Wealthy gentlemen D. Merchants and craftsmen E. -

An Archaeological Inventory of Alamance County, North Carolina

AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVENTORY OF ALAMANCE COUNTY, NORTH CAROLINA Alamance County Historic Properties Commission August, 2019 AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVENTORY OF ALAMANCE COUNTY, NORTH CAROLINA A SPECIAL PROJECT OF THE ALAMANCE COUNTY HISTORIC PROPERTIES COMMISSION August 5, 2019 This inventory is an update of the Alamance County Archaeological Survey Project, published by the Research Laboratories of Anthropology, UNC-Chapel Hill in 1986 (McManus and Long 1986). The survey project collected information on 65 archaeological sites. A total of 177 archaeological sites had been recorded prior to the 1986 project making a total of 242 sites on file at the end of the survey work. Since that time, other archaeological sites have been added to the North Carolina site files at the Office of State Archaeology, Department of Natural and Cultural Resources in Raleigh. The updated inventory presented here includes 410 sites across the county and serves to make the information current. Most of the information in this document is from the original survey and site forms on file at the Office of State Archaeology and may not reflect the current conditions of some of the sites. This updated inventory was undertaken as a Special Project by members of the Alamance County Historic Properties Commission (HPC) and published in-house by the Alamance County Planning Department. The goals of this project are three-fold and include: 1) to make the archaeological and cultural heritage of the county more accessible to its citizens; 2) to serve as a planning tool for the Alamance County Planning Department and provide aid in preservation and conservation efforts by the county planners; and 3) to serve as a research tool for scholars studying the prehistory and history of Alamance County. -

Link.Net Chancellor General Davis Lee Wright, Esq., P.O

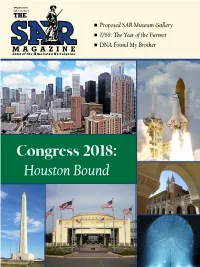

SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 n Proposed SAR Museum Gallery n 1768: The Year of the Farmer n DNA Found My Brother Congress 2018: Houston Bound SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 6 16 6 2018 Congress to Convene 10 America’s Heritage and the 22 Newly Acquired Letters in Houston SAR Library Reveal More About the Maryland 400 7 Amendment Proposal/ 11 The Proposed SAR Museum Leadership Medical Committee Gallery 24 State Society & Chapter News 8 Nominating Committee Report/Butler Awarded 16 250th Series: 1768—The Year 38 In Our Memory/ Medal of Honor of the Farmer New Members 9 Newsletter Competitions 20 DNA Found My Brother 47 When You Are Traveling THE SAR MAGAZINE (ISSN 0161-0511) is published quarterly (February, May, August, November) and copyrighted by the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. Periodicals postage paid at Louisville, KY and additional mailing offices. Membership dues include The SAR Magazine. Subscription rate $10 for four consecutive issues. Single copies $3 with checks payable to “Treasurer General, NSSAR” mailed to the HQ in Louisville. Products and services advertised do not carry NSSAR endorsement. The National Society reserves the right to reject content of any copy. Send all news matter to Editor; send the following to NSSAR Headquarters: address changes, election of officers, new members, member deaths. Postmaster: Send address changes to The SAR Magazine, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. PUBLISHER: STAFF DIRECTORY President General Larry T. Guzy As indicated below, staff members have an email address and an extension number of the automated 4531 Paper Mill Road, SE telephone system to simplify reaching them. -

Tuscarora Trails: Indian Migrations, War, and Constructions of Colonial Frontiers

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2007 Tuscarora trails: Indian migrations, war, and constructions of colonial frontiers Stephen D. Feeley College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Feeley, Stephen D., "Tuscarora trails: Indian migrations, war, and constructions of colonial frontiers" (2007). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623324. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-4nn0-c987 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tuscarora Trails: Indian Migrations, War, and Constructions of Colonial Frontiers Volume I Stephen Delbert Feeley Norcross, Georgia B.A., Davidson College, 1996 M.A., The College of William and Mary, 2000 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Lyon Gardiner Tyler Department of History The College of William and Mary May, 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. APPROVAL SHEET This dissertation is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Stephen Delbert F eele^ -^ Approved by the Committee, January 2007 MIL James Axtell, Chair Daniel K. Richter McNeil Center for Early American Studies 11 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

1 the Story of the Faulkner Murals by Lester S. Gorelic, Ph.D. the Story Of

The Story of the Faulkner Murals By Lester S. Gorelic, Ph.D. The story of the Faulkner murals in the Rotunda begins on October 23, 1933. On this date, the chief architect of the National Archives, John Russell Pope, recommended the approval of a two- year competing United States Government contract to hire a noted American muralist, Barry Faulkner, to paint a mural for the Exhibit Hall in the planned National Archives Building.1 The recommendation initiated a three-year project that produced two murals, now viewed and admired by more than a million people annually who make the pilgrimage to the National Archives in Washington, DC, to view two of the Charters of Freedom documents they commemorate: the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States of America. The two-year contract provided $36,000 in costs plus $6,000 for incidental expenses.* The contract ended one year before the projected date for completion of the Archives Building’s construction, providing Faulkner with an additional year to complete the project. The contract’s only guidance of an artistic nature specified that “The work shall be in character with and appropriate to the particular design of this building.” Pope served as the contract supervisor. Louis Simon, the supervising architect for the Treasury Department, was brought in as the government representative. All work on the murals needed approval by both architects. Also, The United States Commission of Fine Arts served in an advisory capacity to the project and provided input critical to the final composition. The contract team had expertise in art, architecture, painting, and sculpture. -

An Educator's Guide to the Story of North Carolina

Story of North Carolina – Educator’s Guide An Educator’s Guide to The Story of North Carolina An exhibition content guide for teachers covering the major themes and subject areas of the museum’s exhibition The Story of North Carolina. Use this guide to help create lesson plans, plan a field trip, and generate pre- and post-visit activities. This guide contains recommended lessons by the UNC Civic Education Consortium (available at http://database.civics.unc.edu/), inquiries aligned to the C3 Framework for Social Studies, and links to related primary sources available in the Library of Congress. Updated Fall 2016 1 Story of North Carolina – Educator’s Guide The earth was formed about 4,500 million years (4.5 billion years) ago. The landmass under North Carolina began to form about 1,700 million years ago, and has been in constant change ever since. Continents broke apart, merged, then drifted apart again. After North Carolina found its present place on the eastern coast of North America, the global climate warmed and cooled many times. The first single-celled life-forms appeared as early as 3,800 million years ago. As life-forms grew more complex, they diversified. Plants and animals became distinct. Gradually life crept out from the oceans and took over the land. The ancestors of humans began to walk upright only a few million years ago, and our species, Homo sapiens, emerged only about 120,000 years ago. The first humans arrived in North Carolina approximately 14,000 years ago—and continued the process of environmental change through hunting, agriculture, and eventually development. -

American Self-Government: the First & Second Continental Congress

American Self-Government: The First and Second Continental Congress “…the eyes of the virtuous all over the earth are turned with anxiety on us, as the only depositories of the sacred fire of liberty, and…our falling into anarchy would decide forever the destinies of mankind, and seal the political heresy that man is incapable of self-government.” ~ Thomas Jefferson Overview Students will explore the movement of the colonies towards self-government by examining the choices made by the Second Continental Congress, noting how American delegates were influenced by philosophers such as John Locke. Students will participate in an activity in which they assume the role of a Congressional member in the year 1775 and devise a plan for America after the onset of war. This lesson can optionally end with a Socratic Seminar or translation activity on the Declaration of Independence. Grades Middle & High School Materials • “American Self Government – First & Second Continental Congress Power Point,” available in Carolina K- 12’s Database of K-12 Resources (in PDF format): https://k12database.unc.edu/wp- content/uploads/sites/31/2021/01/AmericanSelfGovtContCongressPPT.pdf o To view this PDF as a projectable presentation, save the file, click “View” in the top menu bar of the file, and select “Full Screen Mode” o To request an editable PPT version of this presentation, send a request to [email protected] • The Bostonians Paying the Excise Man, image attached or available in power point • The Battle of Lexington, image attached or available in power -

Danbury Raid and the Forgotten General

Danbury Raid and the Forgotten General “I am dying, but with a strong hope and persuasion that my country will gain her independence.” General David Wooster’s dying words after being mortally wounded by the British at the Battle of Ridgefield on the Danbury Raid, 1777 Start/Finish: Compo Beach / Cedar Point, Westport, Connecticut Distance: 61.5 miles Terrain: In town cycling, country roads and some busier sections Difficulty: Hilly with some steep grades Connecticut supplied more food and cannons to the Continental Army during the American Revolution than any other state, which explains why it was eventually known as the “provision state.” Soldiers cannot survive for long if they must rely on the local population for food, clean water, clothing, tents, blankets and other basics, especially in an environment where more colonists were Loyalists or neutral than most contemporary Americans realize. The Rebels simply had to have an organized, well-protected supply line. Danbury, located just 25 miles from Long Island Sound and between New York and Boston, was ideally situated for a major depot. After American victories at Trenton and Princeton in 1776 and 1777, the British felt an urgent need to go on the offensive. They took advantage of their control of the waterways and moved 26 ships off of Compo Beach in Fairfield as a staging area for an attack on Danbury. Today there’s a fantastic Cannon Revolutionary War Memorial at the spot in Westport where the Redcoats came ashore on April 25, 1777 under the leadership of British New York Governor Tryon. Nearly 2000 British troops moved quickly in a forced march through the farm- covered landscape.