Shanghai Manual a Guide for Sustainable Urban Development in the 21St Century· 2018 Annual Report Preface 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three Iconic Towers That Will Illuminate Liverpool's Skyline

1 Executive summary Three iconic towers that will illuminate Liverpool’s skyline Infinity Waters is a new residential property Occupying a prime area which is currently investment in a highly desirable Liverpool benefitting from over £5.5 billion worth waterfront location. of investment, the development is well- positioned to appeal to the city’s thriving For a long time, UK buy-to-let property rental market. has offered investors rising rental income and capital growth prospects. Over time In a time where income from property the market has changed. High property has been affected by tax changes, 7% prices in London and other large cities assured NET returns are offered per annum have forced investors to look further afield, to safeguard the first three years of the allowing key regional cities with strong investment. economies to overtake the capital as investment hotspots. NET Fully 7% P.A. managed 20% assured for studio, 1 and 2 early investor 3 years bed apartments discount 2 Introducing Infinity Waters Investment at a Glance: A Magnificent Residential Development A selection of stylish, new-build apartments An array of high quality, on-site facilities Incredible river and city views Prime Waterfront Location £5.5 billion regeneration area Liverpool’s city centre and business district Fantastic transport links and local amenities Income Generating Asset Infinity Waters is a magnificent multi-tower development World-class facilities within this signature address will Assured rental returns that will provide uninterrupted views over the River captivate the intrinsic desires of an aspirational, young Mersey and Liverpool’s vibrant city centre. -

Introducing Infinity Waters Investment at a Glance

1 Executive summary Three iconic towers that will illuminate Liverpool’s skyline Infinity Waters is a new residential property benefitting from over £5.5 billion worth investment in a highly desirable Liverpool of investment, the development is well- waterfront location. positioned to appeal to the city’s thriving rental market. For a long time, UK buy-to-let property has offered investors rising rental income In a time where income from property and capital growth prospects. Over time has been affected by tax changes, 7% the market has changed. High property assured NET returns are offered per annum prices in London and other large cities to safeguard the first three years of the have forced investors to look further afield, investment. allowing key regional cities with strong economies to overtake the capital as investment hotspots. Occupying a prime area which is currently NET Fully 7% P.A. managed 20% assured for studio, 1 and 2 early investor 3 years bed apartments discount 2 Introducing Infinity Waters Investment at a Glance: A Magnificent Residential Development A selection of stylish, new-build apartments An array of high quality, on-site facilities Incredible river and city views Prime Waterfront Location £5.5 billion regeneration area Liverpool’s city centre and business district Fantastic transport links and local amenities Income Generating Asset Infinity Waters is a magnificent multi-tower development World-class facilities within this signature address will Assured rental returns that will provide uninterrupted views over the River captivate the intrinsic desires of an aspirational, young Mersey and Liverpool’s vibrant city centre. -

(0)20 7211 6664 4Th February 2020 Dear Dr Rössl

Cultural Diplomacy Team 4th Floor 100 Parliament Street London SW1A 2BQ T: +44 (0)20 7211 6664 4th February 2020 Dear Dr Rössler, State of Conservation Report for the Liverpool Marine Mercantile City World Heritage Site: United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland In accordance with Decision 43 COM 7A.47 we submit the following report on the state of conservation of Liverpool Marine Mercantile City World Heritage Site. This report is structured in line with the template provided in the Operational Guidelines. The relevant sections of the Committee decision are printed in italics for ease of reference. The UK State Party is content for this report to be posted on the UNESCO World Heritage Centre website. If you require further information or clarification do please do not hesitate to contact me. Kind regards, Enid Williams World Heritage Policy Advisor ONIO MU M ND RI T IA A L • P • W L STATE OF CONSERVATION REPORTS O A I R D L D N H O E M R I E T IN AG O E • PATRIM BY THE STATES PARTIES United Nations World Heritage Cultural Organization Convention (in compliance with Paragraph 169 of the Operational Guidelines) LIVERPOOL MARITIME MERCANTILE CITY (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) (C1150) 1. Executive Summary This report addresses the issues raised by the World Heritage Committee in its Decision 43 COM 7A.47. The decision has as its focus the Liverpool Waters development scheme, part of which lies in the World Heritage Site with the remainder in the Buffer Zone. It confirms that Liverpool City Council (LCC) and Peel Holdings (the Liverpool Waters developer), with the advice of Historic England (HE) and the engagement of the State Party are working to safeguard the OUV of the property, including the conditions of authenticity and integrity and the protection and management regime. -

Justification for 'Scrapping the Sky'

10.2478/jbe-2019-0004 JUSTIFICATION FOR ‘SCRAPPING THE SKY’ A COMPREHENSIVE INTERNATIONAL REVIEW OF SKYSCRAPERS/HIGH-RISE BUILDINGS FROM AN URBAN DESIGN PERSPECTIVE Tamas Lukovich Institute of Architecture, Faculty of Architecture and Civil Engineering, Szent Istvan University, Budapest, Hungary Abstract: The magic ‘vertical’ has always been a spiritually distinctive preoccupation of architecture throughout history. The paper intends to examine, from a series of perspectives, if the high-rise in principle is a good thing. The focus is on urban design implications, however engineering challenges and their design solutions are inseparable aspects of the problematic. It is also to further demystify some ideologies still attached to their widespread application. It concludes that there is a new awareness evolving about high-rise design that is superior to previous approaches. Keywords: changing high-rise definitions, historic height contest, symbolic messages, technical challenges, urban design ideologies and myths, density and form fundamentals, high-rise typology, vertical eco-architecture 1. INTRODUCTION: THE PHENOMENON, AIMS AND DEFINITIONS According to Giedion, our attitude related to the vertical is rooted in our subconscious mind. Among the infinite number of directions and angles, it is separated as a single one that becomes a baseline and reference for comparison. It makes the main endeavour of architecture, i.e. the victory over the force of gravitation, visible. [1] Therefore, building vertical structures has almost always had a spiritual importance and has often been a symbolic event over the history of mankind. However, it seems that there are still some myths around the justification of high-rise buildings or skyscrapers, even among professional planners and architects. -

UNIQUELY PHUKET Boat Pattana Brings Unparalleled Design and Peerless Quality to Its Villas

ASIA'S PREMIUM REAL ESTATE MAGAZINE ISSUE 027 ๐Q2 2019 UNIQUELY PHUKET Boat Pattana brings unparalleled design and peerless quality to its villas UK REAL ESTATE PROPTECH’S HERE ISLAND REPORT BREXIT DOESN’T DENT BUT WHAT IS IT AND IS SOUTHEAST AN EXCLUSIVE LOOK AT PHUKET INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES ASIA READY? PROPERTY DEMAND 42 50 58 1 “Specialty of Pirom At Vineyard project is the intention of project owner, Mr. Piya Bhirombhakdi, to create quality society where not anyone could belong easily. Glamorous outstanding land on Khoyai surrounded by four lakes and mountains allows your living to feel relaxation in the true nature.” Kingdom of Nature. Aesthetics of luxury living albeit simple in the best estate on Khao Yai. Buranit Yuktanuntana CEO, PIROM AT VINEYARD Pirom at Vineyard Living Beyond Luxury Pirom At Vineyard is a real estate project for those passionate privacy and Developer: Piya Interna�onal nature surrounded by peaceful nature, a hidden paradise of unsoiled land Land Area: 800 Rais ‘Living Beyond Luxury’ No. of zone: 2 zone (A and B) nestled in Khao Yai’s gorgeous hillside. concept provides Product type: Land for Sale more than luxury that cannot be found in the city ,which connects you to Architect: Boonlert Hemvijitraphan nature and live luxuriously. Landscape design, something not seen as a priority Lanscape: Wannaporn Phornprapha at most luxury developments, was emphasised at Pirom At Vineyard. Loca�on: 234 Moo 5 , Phaya-Yen Wannaporn Pui Phornprapa of P Landscape was entrusted to create a space sub-district , Pak Chong that maintains the connec�on of land and architecture. -

Liverpool Residential Development Update

LIVERPOOL RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT UPDATE October 2018 Foreword 2018 has been a significant year and turning point for Liverpool’s housing market. Named as one of the friendliest cities in which to live, it seems that more and more people want to live here and the city’s population is now rising. A recent report by the Centre for Cities stated that Liverpool City Centre’s population grew by over 180% between 2002 and 2015, the highest percentage in the UK. We have a clear need to build new homes for that growing population. Based on our current estimates, we need to develop 30,000 new homes by 2030. Since I became Mayor in April 2012, over 9,500 homes have been built by both the public and private sectors, with more than 5,000 of these being homes I promised under the Housing Delivery Plan. I am also happy to report that all of our targets for bringing empty homes back into use have seen almost double the target actually being achieved. Over 8,000 new homes are currently being built on schemes that have commenced, and a further 25,000 either have or are seeking planning approval. On top of these, several thousand more (such as at Liverpool Waters) will be coming forward for planning approval in the next few years. Whilst the Strategic Housing Delivery Plan is already past halfway to delivering 1,500 homes, we have now set ourselves a new target of building a further 10,000 homes as part of our own new ethical housing company “Foundations”. -

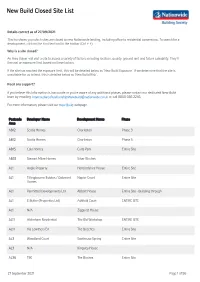

New Build Closed Site List

New Build Closed Site List Details correct as of 27/09/2021 This list shows you which sites are closed to new Nationwide lending, including office to residential conversions. To search for a development, click on the Find text tool in the toolbar (Ctrl + F). Why is a site closed? An Area Valuer will visit a site to assess a variety of factors including location, quality, ground rent and future saleability. They’ll then set an exposure limit based on these factors. If the site has reached the exposure limit, this will be detailed below as ‘New Build Exposure’. If we determine that the site is unsuitable for us to lend, this is detailed below as ‘New Build Risk’. Need any support? If you believe this information is inaccurate or you’re aware of any additional phases, please contact our dedicated New Build team by emailing [email protected] or call 0800 085 2245. For more information, please visit our New Build webpage. Postcode Developer Name Development Name Phase Area AB12 Scotia Homes Charleston Phase 3 AB12 Scotia Homes Charleston Phase 5 AB15 Cala Homes Cults Park Entire Site AB33 Stewart Milne Homes Silver Birches AL1 Angle Property Hertfordshire House Entire Site AL1 Tillingbourne Estates / Oakmont Napier Court Entire Site Homes AL1 Permitted Developments Ltd Abbott House Entire Site - Building through AL1 E Butler (Properties Ltd) Ashfield Court ENTIRE SITE AL1 N/A Ziggurat House AL11 Aldenham Residential The Old Workshop ENTIRE SITE AL11 Via Lowthers EA The Beeches Entire Site AL3 Woodland Court -

Land at 122 Old Hall Street, Liverpool Prime Development

FOR SALE – Land at 122 Old Hall Street, Liverpool OVATUS 1 - Planning permission for 168 apartments Ovatus 1 Prime Development Opportunity • Opportunity to purchase a prime residential development opportunity • Further opportunity to acquire the adjacent site, with pre-application proposals for redevelopment for 538 apartments (further details • Situated in a prominent position to the north of Liverpool City Centre and available upon request) within a short walk of Liverpool Lime Street Station • Opportunity to create a stunning landmark for Liverpool in a location • Well located for The Albert Dock and Liverpool One which provide an which will be a vibrant place to live, work and visit array of retail outlets and restaurants • Freehold • Ovatus 1 has planning consent granted for 168 apartments • Offers are invited in the region of £2,500,000 • Neighbouring Kier’s £200m Pall Mall development – comprising a 400,000 sq ft Grade A office and 281 bedroom hotel Ovatus 1 Opportunity by further negotiation Residential Development Opportunity LOCATION Location Leeds Street leads from The Strand which runs along the main waterside of the city centre to the rear of the Three Graces and Albert Dock to Scotland Road Liverpool is the UK’s fifth largest city. and eastwards via the A580 towards the M62 Combined with Greater Manchester the two motorway. The development itself land itself can be regions are the driving force of the £149 accessed directly from Old Hall Street, or via billion North West Economy, with a population vehicular access to the rear from Back Leeds Street. of 7 million. Nearby Developments Liverpool has a population of c.491,500 (ONS 2017 estimate) and a wider metropolitan borough population of 1,544,400. -

LIVERPOOL DEVELOPMENT UPDATE October 2018

LIVERPOOL DEVELOPMENT UPDATE October 2018 Welcome Welcome to the 2018 edition of the Liverpool Development Update. As you will discover within these pages, Liverpool is in the midst of an unprecedented renaissance - with the city on course to attract over £1 billion in new developments for the 6th consecutive year! Indications are showing that both 2019 and 2020 are set to continue seeing such high levels of investment, bringing new homes; leisure, health and education facilities; and a mixture of offices/industrial and commercial space creating new jobs to support this city’s growing economy and rising population. Since I became Mayor in 2012, there has been over £5.7 billion invested by the public and private sectors across the city, with just short of £3 billion of that (more than half) being invested in our neighbourhoods. In that time: 9,700 new homes have been built; Over 5,000 empty homes have been brought back into use; and 12.3 million square feet of floorspace has been built or refurbished to provide space for over 19,000 jobs. Encouragingly, 2018 has seen several larger schemes begin that will underpin growth for the coming decade, in particular the first four residential schemes on the much anticipated Liverpool Waters, and we are making steady progress in getting ready to begin building the new cruise liner terminal and associated hotel development. Progress is also evident at the £1bn Paddington Village scheme, with its first two schemes now underway; and more due to start next year. In the residential sector, my original target to build 5,000 new homes has been surpassed, whilst the Council’s own ethical new housing company Liverpool Foundation Homes Ltd is now up and running with its first two FRONT COVER: schemes already on site. -

LIVERPOOL DEVELOPMENT UPDATE March 2019

LIVERPOOL DEVELOPMENT UPDATE March 2019 Welcome Welcome to the March 2019 edition of the Liverpool Development Update. As you will discover within these pages, Liverpool is in the midst of an unprecedented renaissance - with the City on course to attract over £1 billion in new developments for the 5th consecutive year! Indications are showing that both 2019 and 2020 are set to continue seeing such high levels of investment, bringing new homes; leisure, health and education facilities; and a mixture of offices/industrial and commercial space creating new jobs to support this city’s growing economy and rising population. Since I became Mayor in 2012, there has been over £6.3 billion invested by the public and private sectors across the City, with £3.27 billion of that (more than half) being invested in our neighbourhoods. In that time: 11,220 new homes have been built; Over 5,000 empty homes have been brought back into use; and 12.4 million square feet of floorspace has been built or refurbished to provide space for over 21,000 jobs. Encouragingly, 2018 saw several larger schemes begin that will underpin growth for the coming decade, in particular the first four residential schemes on the much anticipated Liverpool Waters, and we are making steady progress in getting ready to begin building the new cruise liner terminal and associated hotel development. Progress is also evident at the £1bn Paddington Village scheme, with its first four schemes now underway; and more due to start next year. In the residential sector, my original target to build 5,000 new homes has been surpassed, whilst the Council’s own ethical new housing company Liverpool Foundation Homes Ltd is now up and running with its first two FRONT COVER: schemes already on site. -

MIPIM Awards 2016 Finalists BEST HEALTHCARE

Official sponsor: Official press partner: MIPIM Awards 2016 Finalists BEST HEALTHCARE DEVELOPMENT sponsored by Aabenraa Psychiatric Hospital Aabenraa, Denmark Developer: Region Syddanmark Architect: White Arkitekter A/S, DEVE Architects Other: ArkPlan Landscape, Wessberg A/S Engineers, White AB Aabenraa Psychiatric Hospital is an extension to the existing general hospital in Aabenraa, and it consolidates the region's psychiatric facilities in one efficient and environmentally sustainable location. There are eight different hospital wings accommodating a variety of age-ranges and disorders, spread across a large slope, with each room having ample access to light and green spaces. Hospital of the J.W. Goethe University Frankfurt am Main, Germany Developer: The State of Hesse, represented by Hessian Construction Management Architect: Nickl & Partner Architekten AG Other: IB Süss, IG Haringer + Müller mbH, PRO-Elektroplan GmbH, IB Sorge, LA Schmidt, IB Dr. Ressel In the 1970’s the Frankfurt University Hospital was a state-of-the-art medical centre. New demands and a changing attitude to medicine, placing the patient’s needs at the centre of hospital design, have necessitated the renovation and extension of the hospital. A projecting roof connects the clinical, teaching and research units of the development and draws attention to the large glazed entrance hall that forms the interface between the university and the hospital. The exterior grounds are part of the overall architectural plan to closely link the hospital and the public zone along the riverbank. McGill University Health Centre (MUHC) Montreal, Canada Developer: Groupe Immobilier santé McGill (GISM) Architect: IBI Group Architects / Beinhaker Architecte Other: HDR Architecture Canada, Yelle Maillé architectes associés, NFOE et associés architects The MUHC Glen Campus is a state-of-the-art hospital, research and academic facility comprising 217,500 sqm of building area. -

Eldon-Grove-Brochure.Pdf

Steeped In History Cherished By The City Now Yours To Own Welcome To Eldon Grove EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: In The First 2 Years 2017 marks an important year, it marks the beginning of one of the biggest single regeneration projects the UK has ever seen, Liverpool Earn Up To £27,993 Waters. Backed by the government, the £5 billion project will transform 150 acres of historic dockland and will completely transform the Vauxhall area of Liverpool. Understandably, the area has now been tipped as one of the hottest property investments in the UK. We would like to introduce a rare opportunity to own a piece of a treasured Liverpool landmark, which sits on the doorstep to Liverpool Waters, Eldon Grove. INVESTMENT OVERVIEW: Phase 1 of just 45 luxury 1, 2 & 3 bedroom apartments Complete refurbishment of iconic Grade II-listed building Investor launch prices up to 14.5% below official RICS valuation 7% NET yield assured for the first 2 years (up to £27,993) Designed by the impressive DAY Architectural Ltd Fully managed by the established Eldonian Brookhaven Investor discounted launch prices from as little as £99,750 3 “ IT’S A GREAT PRIVILEGE TO WORK ON DESIGNING AND BRINGING BACK AN IMPORTANT PIECE OF LIVERPOOL HISTORY” - Tony Catterall, Day Architectural Ltd WHY LIVERPOOL? Liverpool is at the centre of the UK’s second largest regional economy with access to six million customers. It’s economy is worth more than £121 billion and home to over 252,000 businesses. Additionally, it has the largest wealth management industry in the UK outside London, worth £12billion.