MEANINGS of BULLYING in the GREEK CONTEXT an Exploration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10147225.Pdf (1.609Mb)

BAŞKENT ÜNİVERSİTESİ FEN BİLİMLERİ ENSTİTÜSÜ SPOR KULÜPLERİNDE MAÇ ÖNCESİ TAKIM KURMA PROBLEMİ İÇİN YENİ KARAR MODELLERİ: VOLEYBOL KULÜBÜ UYGULAMASI GERÇEK BUDAK DOKTORA TEZİ 2017 SPOR KULÜPLERİNDE MAÇ ÖNCESİ TAKIM KURMA PROBLEMİ İÇİN YENİ KARAR MODELLERİ: VOLEYBOL KULUBÜ UYGULAMASI NEW DECISION MODELS FOR TEAM FORMATION PROBLEM OF SPORTS CLUBS BEFORE THE MATCH STAGE: A VOLLEYBALL CLUB APPLICATION GERÇEK BUDAK Başkent Üniversitesi Lisansüstü Eğitim Öğretim ve Sınav Yönetmeliğinin ENDÜSTRİ Mühendisliği Anabilim Dalı İçin Öngördüğü DOKTORA TEZİ olarak hazırlanmıştır. 2017 “SPOR KULÜPLERİNDE MAÇ ÖNCESİ TAKIM KURMA PROBLEMİ İÇİN YENİ KARAR MODELLERİ: VOLEYBOL KULUBÜ UYGULAMASI” başlıklı bu çalışma, jürimiz tarafından, 08/05/2017 tarihinde, ENDÜSTRİ MÜHENDİSLİĞİ ANABİLİM DALI 'nda DOKTORA TEZİ olarak kabul edilmiştir. Başkan : Prof. Dr. Berna DENGİZ Üye (Danışman) : Prof. Dr. İmdat KARA Üye : Prof. Dr. Refail KASIMBEYLİ Üye : Prof. Dr. Ergün ERASLAN Üye : Doç. Dr. Yusuf Tansel İÇ ONAY ..../05/2017 Prof. Dr. Emin AKATA Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü Müdürü BAŞKENT ÜNİVERSİTESİ FEN BİLİMLERİ ENSTİTÜSÜ DOKTORA TEZ ÇALIŞMASI ORİJİNALLİK RAPORU Tarih: 12 / 05 / 2017 Öğrencinin Adı, Soyadı : Gerçek Budak Öğrencinin Numarası : 21220194 Anabilim Dalı : Endüstri Mühendisliği Programı : Doktora Programı Danışmanın Unvanı/Adı, Soyadı : Prof. Dr. İmdat Kara Tez Başlığı : Spor Kulüplerinde Maç Öncesi Takım Kurma Problemi İçin Yeni Karar Modelleri: Voleybol Kulübü Uygulaması Yukarıda başlığı belirtilen Doktora tez çalışmamın; Giriş, Ana Bölümler ve Sonuç Bölümünden -

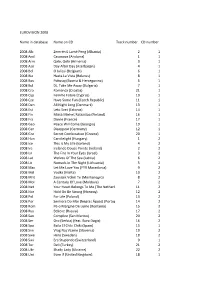

EUROVISION 2008 Name in Database Name on CD Track Number CD

EUROVISION 2008 Name in database Name on CD Track number CD number 2008 Alb Zemrën E Lamë Peng (Albania) 2 1 2008 And Casanova (Andorra) 1 1 2008 Arm Qele, Qele (Armenia) 3 1 2008 Aze Day After Day (Azerbaijan) 4 1 2008 Bel O Julissi (Belgium) 6 1 2008 Bie Hasta La Vista (Belarus) 8 1 2008 Bos Pokusaj (Bosnia & Herzegovina) 5 1 2008 Bul DJ, Take Me Away (Bulgaria) 7 1 2008 Cro Romanca (Croatia) 21 1 2008 Cyp Femme Fatale (Cyprus) 10 1 2008 Cze Have Some Fun (Czech Republic) 11 1 2008 Den All Night Long (Denmark) 13 1 2008 Est Leto Svet (Estonia) 14 1 2008 Fin Missä Miehet Ratsastaa (Finland) 16 1 2008 Fra Divine (France) 17 1 2008 Geo Peace Will Come (Georgia) 19 1 2008 Ger Disappear (Germany) 12 1 2008 Gre Secret Combination (Greece) 20 1 2008 Hun Candlelight (Hungary) 1 2 2008 Ice This Is My Life (Iceland) 4 2 2008 Ire Irelande Douze Pointe (Ireland) 2 2 2008 Isr The Fire In Your Eyes (Israel) 3 2 2008 Lat Wolves Of The Sea (Latvia) 6 2 2008 Lit Nomads In The Night (Lithuania) 5 2 2008 Mac Let Me Love You (FYR Macedonia) 9 2 2008 Mal Vodka (Malta) 10 2 2008 Mnt Zauvijek Volim Te (Montenegro) 8 2 2008 Mol A Century Of Love (Moldova) 7 2 2008 Net Your Heart Belongs To Me (The Netherlands) 11 2 2008 Nor Hold On Be Strong (Norway) 12 2 2008 Pol For Life (Poland) 13 2 2008 Por Senhora Do Mar (Negras Águas) (Portugal) 14 2 2008 Rom Pe-o Margine De Lume (Romania) 15 2 2008 Rus Believe (Russia) 17 2 2008 San Complice (San Marino) 20 2 2008 Ser Oro (Serbia) (feat. -

From Assimilation to Kalomoira: Satellite Television and Its Place in New York City’S Greek Community

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Directory of Open Access Journals © 2011, Global Media Journal -- Canadian Edition Volume 4, Issue 1, pp. 163-178 ISSN: 1918-5901 (English) -- ISSN: 1918-591X (Français) From Assimilation to Kalomoira: Satellite Television and its Place in New York City’s Greek Community Michael Nevradakis University of Texas at Austin, United States Abstract: This paper examines the role that imported satellite television programming from Greece has played in the maintenance and rejuvenation of Greek cultural identity and language use within the Greek-American community of New York City—the largest and most significant in the United States. Four main concepts guide this paper, based on prior theoretical research established in the field of Diaspora studies: authenticity, assertive hybridity, cultural capital, and imagined communities. Satellite television broadcasts from Greece have targeted the audience of the Hellenic Diaspora as an extension of the homeland, and as a result, are viewed as more “authentic” than Diaspora-based broadcasts. Assertive hybridity is exemplified through satellite programming such as reality shows and the emergence of transnational pop stars such as Kalomoira, who was born and raised in New York but attained celebrity status in Greece as the result of her participation on the Greek reality show Fame Story. Finally, satellite television broadcasts from Greece have fostered the formation of a transnational imagined community, linked by the shared viewing of Greek satellite programming and the simultaneous consumption of Greek pop culture and acquisition of cultural capital. All of the above concepts are evident in the emergence of a Greek “café culture” and “sports culture”, mediated by satellite television and visible in the community’s public spaces. -

Eurovision 2008 De La Chanson

Lieu : Beogradska Arena de Orchestre : - Belgrade (Serbie) Présentation : Jovana Jankovic & Date : Mardi 20 Mai Zeljko Joksimovic Réalisateur : Sven Stojanovic Durée : 2 h 02 Même si nombre de titres yougoslaves étaient signés par des Serbes, en 2007 la Serbie fraîchement indépendante est devenue le deuxième pays à remporter le concours Eurovision de la chanson dès sa première participa- tion. C'est dans la Beogradska Arena de Belgrade que l'Europe de la chan- son se retrouvera cette année. Le concours organisé par la RTS est placé sous le signe de la "confluence des sons" et la scène, créée par l'américain David Cushing, symbolise la confluence des rivières Sava et Danube qui arrosent la capitale serbe. Zeljko Joksimovic, le brillant représentant serbo- monténégrin en 2004, est associé à l'animatrice Jovana Jankovic pour pré- senter les trois soirées de ce concours Eurovision 2008. Lors des deux soirées du concours 2008, les votes des émigrés, des pays de l'ex-Yougoslavie et de l'ex-U.R.S.S. avaient réussi à influencer les résul- tats de telle façon qu'aucun pays de l'Europe occidentale n'avait pu atteind- re le top 10. La grogne et les menaces de retrait ont alors été tellement for- tes que l'U.E.R. a du, une nouvelle fois, revoir la formule du concours Eurovision. Le format avec une demi-finale a vécu, vive le format à deux demi-finales. Avec ce système, dans lequel on sépare ceux qui ont une ten- dance un peu trop évidente à se favoriser et où chacun ne vote que dans la demi-finale à laquelle il participe, on espère que l'équité sera respectée. -

Paul Sarbanes Awarded Greece's Highest Honor

✽ CMYK CMYK ✽ O C V ΓΡΑΦΕΙ ΤΗΝ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ Bringing the news ΤΟΥ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ to generations of ΑΠΟ ΤΟ 1915 The National Herald Greek Americans A WEEKLY GREEK AMERICAN PUBLICATION c v www.thenationalherald.com VOL. 11, ISSUE 555 May 31, 2008 $1.00 GREECE: 1.75 EURO Archbishop Demetrios Paul Sarbanes Awarded Greece’s Highest Honor Meets Church and Political Former U.S. Senator Honored with Order of Leaders in Moscow Visit The Phoenix Cross By National Herald Staff such a deep commitment to the Or- By George Kakarnias Special to The National Herald thodox Faith. Special to The National Herald In the evening, the Archbishop BOSTON – Archbishop Demetrios and the delegation were guests of ATHENS – Former U.S. Senator of America concluded a six day offi- Patriarch Alexios at a concert and Paul Sarbanes addressed an event cial visit in Moscow with meetings performance in the Auditorium of organized by the "Constantine and visits of the high ranking eccle- Christ the Savior Cathedral. The Karamanlis Institute for Democra- siastical and political leaders of performance, including music, po- cy" at a central Athens hotel on Russia. Archbishop Demetrios visit- etry and dance, were a continua- Monday, May 26, during a visit to ed Russia upon the invitation of Pa- tion of the celebration of Slavic Let- Greece where he was also be- triarch Alexios of Moscow and All ters Day. stowed Greece's highest honor, the Russia. According to News Releases Before the official visit to the Order of the Phoenix Cross, by the issued by the Greek Orthodox Arch- parliament of the Russian Federa- President of the Republic Karolos diocese of America, Archbishop tion, the Archbishop, accompanied Papoulias. -

Cocoricovision46

le magazine d’eurofans club des fans de l’eurovision cocoricovision46 S.TELLIER 46 french sexuality mai# 2008 édito La langue est-elle un élément nécessaire à la caractérisation d’une culture nationale ? Et dans un monde de plus en plus globalisé, est-ce que l’idée même de culture nationale fait encore sens ? Est-ce que la voix et les mots peuvent-être considérés comme un simple matériau ? Est-ce que la danse où les arts plastiques, parce qu’ils font fi de la parole, ne disent rien des pays dont sont originaires leurs artistes ? Mais surtout, est-ce que l’eurovision est un outil efficace de diffusion ou de prosélytisme culturel et linguistique ? Est-ce qu’écouter Wer liebe lebt permet de découvrir la culture allemande ? Sans que l’un n’empêche l’autre, il est en tout cas plus important de voir les pièces de Pollesch, de lire Goethe ou de visiter Berlin. D’ailleurs, la victoire en serbe de la représentante d’une chaîne de télévision serbe au concours eurovision de la chanson de 2007, SOMMAIRE a-t-elle quelque part dans le monde déclenché des le billet du Président. 02 vocations ou un intérêt Beograd - Serbie . 06 quelconque pour la cette langue ? Belgrade 2008 . 10 53ème concours eurovision de la chanson Chacun trouvera ses réponses, affinera ses demi-finale 1 - 20 mai 2008 . 13 arguments, tout ca ne nous demi-finale 2 - 22 mai 2008 . 32 empêchera pas de nous trémousser sur certains titres finale - 24 mai 2008 . 51 de cette édition 2008, d’être era vincitore - les previews . -

A Sociological Perspective. Gabriella As

THE EVOLUTION OF AMERICAN MUSICAL THEATRE. 1 The Evolution of American Musical Theatre: A Sociological Perspective. Gabriella Asimenou Faculty of Education Music Department Charles University. Thesis Supervisor: Edel Sanders, Ph.D. Prague-July, 2015. THE EVOLUTION OF AMERICAN MUSICAL THEATRE. 2 Declaration: I confirm that this is my own work and the use of all material from other sources has been properly and fully acknowledged. I give my permission to the library of the Faculty of Education of Charles University to have my thesis available for educational purposes. …...................................... …................................ Prague,20th July, 2015. Asimenou Gabriella. THE EVOLUTION OF AMERICAN MUSICAL THEATRE. 3 Abstract. In this paper I analyse the development of musical theatre through the social issues which pervaded society before and which continue to influence our society today. This thesis explores the link between the musicals of the times and concurrent problems such as the world wars, economic depression and racism. Choosing to base this analysis on the social problems of the United States, I tried to highlight the origins and development of the musical theatre art form by combining the influences which may have existed in humanity during the creation of each work. This paper includes research from books, journals, encyclopedias, and websites which together show similar results, that all things in life travel cycles, and that tendencies and patterns in society will unlikely change fundamentally, although it is hoped that the society will nonetheless evolve for the better. Perhaps the most powerful phenomena which will help people to escape from their sociological problems are music and theatre. Keywords: Musicals, Society,Culture. -

Escinsighteurovision2011guide.Pdf

Table of Contents Foreword 3 Editors Introduction 4 Albania 5 Armenia 7 Austria 9 Azerbaijan 11 Belarus 13 Belgium 15 Bosnia & Herzegovina 17 Bulgaria 19 Croatia 21 Cyprus 23 Denmark 25 Estonia 27 FYR Macedonia 29 Finland 31 France 33 Georgia 35 Germany 37 Greece 39 Hungary 41 Iceland 43 Ireland 45 Israel 47 Italy 49 Latvia 51 Lithuania 53 Malta 55 Moldova 57 Norway 59 Poland 61 Portugal 63 Romania 65 Russia 67 San Marino 69 Serbia 71 Slovakia 73 Slovenia 75 Spain 77 Sweden 79 Switzerland 81 The Netherlands 83 Turkey 85 Ukraine 87 United Kingdom 89 ESC Insight – 2011 Eurovision Info Book Page 2 of 90 Foreword Willkommen nach Düsseldorf! Fifty-four years after Germany played host to the second ever Eurovision Song Contest, the musical jamboree comes to Düsseldorf this May. It’s a very different world since ARD staged the show in 1957 with just 10 nations in a small TV studio in Frankfurt. This year, a record 43 countries will take part in the three shows, with a potential audience of 35,000 live in the Esprit Arena. All 10 nations from 1957 will be on show in Germany, but only two of their languages survive. The creaky phone lines that provided the results from the 100 judges have been superseded by state of the art, pan-continental technology that involves all the 125 million viewers watching at home. It’s a very different show indeed. Back in 1957, Lys Assia attempted to defend her Eurovision crown and this year Germany’s Lena will become the third artist taking a crack at the same challenge. -

Eurovisie Top1000

Eurovisie 2017 Statistieken 0 x Afrikaans (0%) 4 x Easylistening (0.4%) 0 x Soul (0%) 0 x Aziatisch (0%) 0 x Electronisch (0%) 3 x Rock (0.3%) 0 x Avantgarde (0%) 2 x Folk (0.2%) 0 x Tunes (0%) 0 x Blues (0%) 0 x Hiphop (0%) 0 x Ballroom (0%) 0 x Caribisch (0%) 0 x Jazz (0%) 0 x Religieus (0%) 0 x Comedie (0%) 5 x Latin (0.5%) 0 x Gelegenheid (0%) 1 x Country (0.1%) 985 x Pop (98.5%) 0 x Klassiek (0%) © Edward Pieper - Eurovisie Top 1000 van 2017 - http://www.top10000.nl 1 Waterloo 1974 Pop ABBA Engels Sweden 2 Euphoria 2012 Pop Loreen Engels Sweden 3 Poupee De Cire, Poupee De Son 1965 Pop France Gall Frans Luxembourg 4 Calm After The Storm 2014 Country The Common Linnets Engels The Netherlands 5 J'aime La Vie 1986 Pop Sandra Kim Frans Belgium 6 Birds 2013 Rock Anouk Engels The Netherlands 7 Hold Me Now 1987 Pop Johnny Logan Engels Ireland 8 Making Your Mind Up 1981 Pop Bucks Fizz Engels United Kingdom 9 Fairytale (Norway) 2009 Pop Alexander Rybak Engels Norway 10 Ein Bisschen Frieden 1982 Pop Nicole Duits Germany 11 Save Your Kisses For Me 1976 Pop Brotherhood Of Man Engels United Kingdom 12 Vrede 1993 Pop Ruth Jacott Nederlands The Netherlands 13 Puppet On A String 1967 Pop Sandie Shaw Engels United Kingdom 14 Apres toi 1972 Pop Vicky Leandros Frans Luxembourg 15 Power To All Our Friends 1973 Pop Cliff Richard Engels United Kingdom 16 Als het om de liefde gaat 1972 Pop Sandra & Andres Nederlands The Netherlands 17 Eres Tu 1973 Latin Mocedades Spaans Spain 18 Love Shine A Light 1997 Pop Katrina & The Waves Engels United Kingdom 19 Only -

Mimis Plessas

:: SEP 2009 $2.95 6 37 14 22 08 21 Greek Americans to 28 host U. S. House and The New A different kind of Senate Leaders Generation of Leaders Universal Care 16 Lefteris Bournias: 29 Clarinet master of St. Spyridon Youth music East and West Help hellenicare 13 10 22 Mimis Plessas: 19 Maria’s Slate featuring… 34 A Man for All Seasons Beverly Hills event A Special Interview My Summer Journey Returns to New York to support Dina Titus with Elli Kokkinou to the Ionian Village 19 20 Harry Markopolos, 26 38 10 the man who Undefined by their HACC Young Professionals 33 Alexi goes to…Hollywood! uncovered Madoff Circumstance Happy Hour A Musical Issue This issue has a lot of music in it, from the new sensation of singing star Elli Kokkinou, to the :: magazine synthesized mix of old and new by clarinet virtuoso Lefteris Bournias, to the long line of popular music tradition by grand master Mimis Plessas. Editor in Chief: Dimitri C. Michalakis I was born in Chios and still love the klarino more [email protected] than any other instrument. The hairs stand on the :: Features Editor back of my head when I hear the clarinet player Katerina Georgiou tuning up before every wedding and the first dance [email protected] usually has me up on the dance floor immediately—and staying there—as long as the :: klarino is playing. And when a virtuoso of both the old and new like Lefteris Bournias Lifestyle Editor Maria Athanasopoulos begins to play a tsifteli in the old style then I feel no pain and life has become just one [email protected] sweet glendi that I wish would never end. -

Murano Glass Diamond-Shaped Pendant - Blue Pendant - Green Code: KC80MURANO BLUE Code: KC80MURANO GREEN $19.95 $19.95

Murano Glass Diamond-Shaped Murano Glass Diamond-Shaped Pendant - Blue Pendant - Green Code: KC80MURANO_BLUE Code: KC80MURANO_GREEN $19.95 $19.95 Murano Glass Cross-Shaped Pendant - Murano Glass Cross-Shaped Pendant - Blue Brown Code: KC90MURANO_BLUE Code: KC90MURANO_BROWN $19.95 $19.95 Murano Glass Cross-Shaped Pendant - Murano Glass Cross-Shaped Pendant - Green Rainbow Code: KC90MURANO_GREEN Code: KC90MURANO_RAINBOW $19.95 $19.95 Murano Glass Cross-Shaped Pendant - Murano Glass Teardrop Pendant - Yellow Amber & Silver Code: KC90MURANO_YELLOW Code: KC95MURANO_AMBER $19.95 $24.95 Murano Glass Teardrop Pendant - Black Murano Glass Teardrop Pendant - Blue & White & Red Code: KC95MURANO_BLACKWHITE Code: KC95MURANO_BLUERED $24.95 $24.95 Murano Glass Teardrop Pendant - Blue Murano Glass Teardrop Pendant - & White Rainbow Code: KC95MURANO_BLUEWHITE Code: KC95MURANO_RAINBOW $24.95 $24.95 Murano Glass Teardrop Pendant - Evil Eye Goodluck Keychain - Koukla for Tri-Color "Doll" in Greek Code: KC95MURANO_TRICOLOR Code: MK2000KOUKLA $24.95 $9.95 Evil Eye Goodluck Keychain - Maggas Evil Eye Goodluck Keychain - Nona for for "Dude" in Greek Godmother in Greek Code: MK2000MAGGAS Code: MK2000NONA $9.95 $9.95 Evil Eye Goodluck Keychain - Nouno for Evil Eye Goodluck Keychain - Pappou Godfather in Greek for Grandfather in Greek Code: MK2000NOUNO Code: MK2000PAPPOU $9.95 $9.95 Evil Eye Goodluck Keychain - Theia for Evil Eye Goodluck Keychain - Theios for Aunt in Greek Uncle in Greek Code: MK2000THEIA Code: MK2000THEIOS $9.95 $9.95 Disclaimer: The list price -

C. Carathéodory, K. Psachos and Byzantine Music: the Letters of Carathéodory to Psachos

Πάπυροι - Επιστημονικό Περιοδικό τόμος 3, 2014 Papyri - Scientific Journal volume 3, 2014 MARIA K. PAPATHANASSIOU, Professor Emerita of the Department of Mathematics at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. Hellas . , , . EΜmail:ΑΡΩ Κ[email protected]ΠΑΠΑΘΑΝΑΣΙΟΥ Ὁμότιμος Καθηγήτρια τοῦ Τμήματος Μαθηματικῶν τοῦ Ἐθνικοῦ καὶ Καποδιστριακοῦ Πανεπιστημίου Ἀθηνῶν Ελλάς – Thessaloniki 2014 Θεσσαλονίκη 2014 ISSN:2241-5106 Πάπυροι - Επιστημονικό Περιοδικό Papyri - Scientific Journal τόμος 3, 2014 volume 3, 2014 www.academy.edu.gr [email protected] C. Carathéodory, K. Psachos and Byzantine music: The letters of Carathéodory to Psachos C. Carathéodory, K. Psachos and Byzantine music: The letters of Carathéodory to Psachos ( ) MARIA K. PAPATHANASSIOU Summary The renowned mathematician C. Carathéodory (1873-1950) was a highly cultured man with excellent knowledge of the fine arts and of the classical music. In this article we present C. Carathéodory’s interest in the Byzantine music as we can deduce from his three letters written in 1905, 1909 and 1924, that were addressed to Konstantinos Psachos (1869-1949), a famous ethnomusicologist and professor of Byzantine music. In 1904 K. Psachos has been sent by the Oecumenical Patriarchate from Constantinople to Athens in order to restore the teaching of the traditional Byzantine music in the Greek Orthodox Church. In this article we publish Carathéodory’s letters fully annotated and we show his special interest in this subject, as follows from his encouraging letter to Psachos so that the latter plans and constructs an Instrument, which could reproduce the musical intervals of the Byzantine music. Moreover two of these letters are the only evidence of two unknown trips of Carathéodory, one to Constantinople and one to Athens.