Case Studies of the Urban Mathematics Collaborative Project: Program Report 91-3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2003 Annual04c 5/23/05 3:55 PM Page 1

Annual04C 5/23/05 4:17 PM Page 1 MILWAUKEE ART MUSEUM Annual Report 2003 Annual04C 5/23/05 3:55 PM Page 1 2004 Annual Report Contents Board of Trustees 2 Board Committees 2 President’s Report 5 Director’s Report 6 Curatorial Report 8 Exhibitions, Traveling Exhibitions 10 Loans 11 Acquisitions 12 Publications 33 Attendance 34 Membership 35 Education and Programs 36 Year in Review 37 Development 44 MAM Donors 45 Support Groups 52 Support Group Officers 56 Staff 60 Financial Report 62 Independent Auditors’ Report 63 This page: Visitors at The Quilts of Gee’s Bend exhibition. Front Cover: Milwaukee Art Museum, Quadracci Pavilion designed by Santiago Calatrava. Back cover: Josiah McElheny, Modernity circa 1952, Mirrored and Reflected Infinitely (detail), 2004. See listing p. 18. www.mam.org 1 Annual04C 5/23/05 3:55 PM Page 2 BOARD OF TRUSTEES COMMITTEES OF Earlier European Arts Committee David Meissner MILWAUKEE ART MUSEUM THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES Jim Quirk Joanne Murphy Chair Dorothy Palay As of August 31, 2004 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Barbara Recht Sheldon B. Lubar Martha R. Bolles Vicki Samson Sheldon B. Lubar Chair Vice Chair and Secretary Suzanne Selig President Reva Shovers Christopher S. Abele Barbara B. Buzard Dorothy Stadler Donald W. Baumgartner Donald W. Baumgartner Joanne Charlton Vice President, Past President Eric Vogel Lori Bechthold Margaret S. Chester Hope Melamed Winter Frederic G. Friedman Frederic G. Friedman Stephen Einhorn Jeffrey Winter Assistant Secretary and Richard J. Glaisner George A. Evans, Jr. Terry A. Hueneke Eckhart Grohmann Legal Counsel EDUCATION COMMITTEE Mary Ann LaBahn Frederick F. -

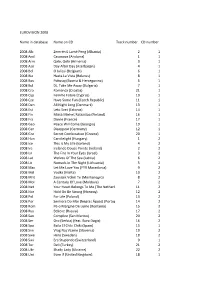

EUROVISION 2008 Name in Database Name on CD Track Number CD

EUROVISION 2008 Name in database Name on CD Track number CD number 2008 Alb Zemrën E Lamë Peng (Albania) 2 1 2008 And Casanova (Andorra) 1 1 2008 Arm Qele, Qele (Armenia) 3 1 2008 Aze Day After Day (Azerbaijan) 4 1 2008 Bel O Julissi (Belgium) 6 1 2008 Bie Hasta La Vista (Belarus) 8 1 2008 Bos Pokusaj (Bosnia & Herzegovina) 5 1 2008 Bul DJ, Take Me Away (Bulgaria) 7 1 2008 Cro Romanca (Croatia) 21 1 2008 Cyp Femme Fatale (Cyprus) 10 1 2008 Cze Have Some Fun (Czech Republic) 11 1 2008 Den All Night Long (Denmark) 13 1 2008 Est Leto Svet (Estonia) 14 1 2008 Fin Missä Miehet Ratsastaa (Finland) 16 1 2008 Fra Divine (France) 17 1 2008 Geo Peace Will Come (Georgia) 19 1 2008 Ger Disappear (Germany) 12 1 2008 Gre Secret Combination (Greece) 20 1 2008 Hun Candlelight (Hungary) 1 2 2008 Ice This Is My Life (Iceland) 4 2 2008 Ire Irelande Douze Pointe (Ireland) 2 2 2008 Isr The Fire In Your Eyes (Israel) 3 2 2008 Lat Wolves Of The Sea (Latvia) 6 2 2008 Lit Nomads In The Night (Lithuania) 5 2 2008 Mac Let Me Love You (FYR Macedonia) 9 2 2008 Mal Vodka (Malta) 10 2 2008 Mnt Zauvijek Volim Te (Montenegro) 8 2 2008 Mol A Century Of Love (Moldova) 7 2 2008 Net Your Heart Belongs To Me (The Netherlands) 11 2 2008 Nor Hold On Be Strong (Norway) 12 2 2008 Pol For Life (Poland) 13 2 2008 Por Senhora Do Mar (Negras Águas) (Portugal) 14 2 2008 Rom Pe-o Margine De Lume (Romania) 15 2 2008 Rus Believe (Russia) 17 2 2008 San Complice (San Marino) 20 2 2008 Ser Oro (Serbia) (feat. -

Eastern Progress 1991-1992 Eastern Progress

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Eastern Progress 1991-1992 Eastern Progress 10-24-1991 Eastern Progress - 24 Oct 1991 Eastern Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: http://encompass.eku.edu/progress_1991-92 Recommended Citation Eastern Kentucky University, "Eastern Progress - 24 Oct 1991" (1991). Eastern Progress 1991-1992. Paper 10. http://encompass.eku.edu/progress_1991-92/10 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Eastern Progress at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Eastern Progress 1991-1992 by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Weekend weather I Style Sports Arts Friday: Chance of Special time showers, high 80, low On the road Music review 59. Saturday and Sun- Take a peek at past Rick Crump, triathlon athlete, Nirvana's new CD day: Showers, high of EKU Homecomings practices what he preaches evolves from the past 75, low near 56. STYLE magazine Page B-7 Page B-3 THE EASTERN PROGRESS Vol. 70/No. 10 October 24,1991 26 pages Student puMMftn of Eastern Kentucky Unrversty, Richmond. Ky. 40475 O The Eastern Progress, 1991 Administrators slash current budget by $2.6 million By dint Riley lege will put 10 percent of its operating bud- the council's November meeting. Eastern happens between the faculty and the student." Managing editor gets, with the exception of salaries, in reserve UK community college system,$3.2 million; budget chief Jim Clark said Wednesday. Arts and Humanities' dean Robinette said Western Kentucky University. $2.4 million. until March 31. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 09/04/2018 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 09/04/2018 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton My Way - Frank Sinatra Wannabe - Spice Girls Perfect - Ed Sheeran Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Broken Halos - Chris Stapleton Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond All Of Me - John Legend Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses Don't Stop Believing - Journey Jackson - Johnny Cash Thinking Out Loud - Ed Sheeran Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Neon Moon - Brooks & Dunn Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Always On My Mind - Willie Nelson Girl Crush - Little Big Town Zombie - The Cranberries Ice Ice Baby - Vanilla Ice Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Piano Man - Billy Joel (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Turn The Page - Bob Seger Total Eclipse Of The Heart - Bonnie Tyler Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Man! I Feel Like A Woman! - Shania Twain Summer Nights - Grease House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals Strawberry Wine - Deana Carter Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley At Last - Etta James I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor My Girl - The Temptations Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Jolene - Dolly Parton Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Love Shack - The B-52's Crazy - Patsy Cline I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys In Case You Didn't Know - Brett Young Let It Go - Idina Menzel These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Livin' On A Prayer - Bon -

Eurovision 2008 De La Chanson

Lieu : Beogradska Arena de Orchestre : - Belgrade (Serbie) Présentation : Jovana Jankovic & Date : Mardi 20 Mai Zeljko Joksimovic Réalisateur : Sven Stojanovic Durée : 2 h 02 Même si nombre de titres yougoslaves étaient signés par des Serbes, en 2007 la Serbie fraîchement indépendante est devenue le deuxième pays à remporter le concours Eurovision de la chanson dès sa première participa- tion. C'est dans la Beogradska Arena de Belgrade que l'Europe de la chan- son se retrouvera cette année. Le concours organisé par la RTS est placé sous le signe de la "confluence des sons" et la scène, créée par l'américain David Cushing, symbolise la confluence des rivières Sava et Danube qui arrosent la capitale serbe. Zeljko Joksimovic, le brillant représentant serbo- monténégrin en 2004, est associé à l'animatrice Jovana Jankovic pour pré- senter les trois soirées de ce concours Eurovision 2008. Lors des deux soirées du concours 2008, les votes des émigrés, des pays de l'ex-Yougoslavie et de l'ex-U.R.S.S. avaient réussi à influencer les résul- tats de telle façon qu'aucun pays de l'Europe occidentale n'avait pu atteind- re le top 10. La grogne et les menaces de retrait ont alors été tellement for- tes que l'U.E.R. a du, une nouvelle fois, revoir la formule du concours Eurovision. Le format avec une demi-finale a vécu, vive le format à deux demi-finales. Avec ce système, dans lequel on sépare ceux qui ont une ten- dance un peu trop évidente à se favoriser et où chacun ne vote que dans la demi-finale à laquelle il participe, on espère que l'équité sera respectée. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 08/09/2016 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 08/09/2016 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Crazy - Patsy Cline Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Don't Stop Believing - Journey Love Yourself - Justin Bieber Shake It Off - Taylor Swift Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond My Girl - The Temptations Like I'm Gonna Lose You - Meghan Trainor Girl Crush - Little Big Town Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Ex's & Oh's - Elle King Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Black Velvet - Alannah Myles Let It Go - Idina Menzel Me Too - Meghan Trainor Baby Got Back - Sir Mix-a-Lot EXPLICIT Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals H.O.L.Y. - Florida Georgia Line Hello - Adele Sweet Home Alabama - Lynyrd Skynyrd When We Were Young - Adele Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Jackson - Johnny Cash Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Summer Nights - Grease Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses Unchained Melody - The Righteous Brothers Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Livin' On A Prayer - Bon Jovi Can't Stop The Feeling - Justin Timberlake Piano Man - Billy Joel I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys All Of Me - John Legend Turn The Page - Bob Seger These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley My Way - Frank Sinatra (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Love Shack - The B-52's 7 Years - Lukas Graham Wannabe - Spice Girls A Whole New World - -

Cocoricovision46

le magazine d’eurofans club des fans de l’eurovision cocoricovision46 S.TELLIER 46 french sexuality mai# 2008 édito La langue est-elle un élément nécessaire à la caractérisation d’une culture nationale ? Et dans un monde de plus en plus globalisé, est-ce que l’idée même de culture nationale fait encore sens ? Est-ce que la voix et les mots peuvent-être considérés comme un simple matériau ? Est-ce que la danse où les arts plastiques, parce qu’ils font fi de la parole, ne disent rien des pays dont sont originaires leurs artistes ? Mais surtout, est-ce que l’eurovision est un outil efficace de diffusion ou de prosélytisme culturel et linguistique ? Est-ce qu’écouter Wer liebe lebt permet de découvrir la culture allemande ? Sans que l’un n’empêche l’autre, il est en tout cas plus important de voir les pièces de Pollesch, de lire Goethe ou de visiter Berlin. D’ailleurs, la victoire en serbe de la représentante d’une chaîne de télévision serbe au concours eurovision de la chanson de 2007, SOMMAIRE a-t-elle quelque part dans le monde déclenché des le billet du Président. 02 vocations ou un intérêt Beograd - Serbie . 06 quelconque pour la cette langue ? Belgrade 2008 . 10 53ème concours eurovision de la chanson Chacun trouvera ses réponses, affinera ses demi-finale 1 - 20 mai 2008 . 13 arguments, tout ca ne nous demi-finale 2 - 22 mai 2008 . 32 empêchera pas de nous trémousser sur certains titres finale - 24 mai 2008 . 51 de cette édition 2008, d’être era vincitore - les previews . -

A Sociological Perspective. Gabriella As

THE EVOLUTION OF AMERICAN MUSICAL THEATRE. 1 The Evolution of American Musical Theatre: A Sociological Perspective. Gabriella Asimenou Faculty of Education Music Department Charles University. Thesis Supervisor: Edel Sanders, Ph.D. Prague-July, 2015. THE EVOLUTION OF AMERICAN MUSICAL THEATRE. 2 Declaration: I confirm that this is my own work and the use of all material from other sources has been properly and fully acknowledged. I give my permission to the library of the Faculty of Education of Charles University to have my thesis available for educational purposes. …...................................... …................................ Prague,20th July, 2015. Asimenou Gabriella. THE EVOLUTION OF AMERICAN MUSICAL THEATRE. 3 Abstract. In this paper I analyse the development of musical theatre through the social issues which pervaded society before and which continue to influence our society today. This thesis explores the link between the musicals of the times and concurrent problems such as the world wars, economic depression and racism. Choosing to base this analysis on the social problems of the United States, I tried to highlight the origins and development of the musical theatre art form by combining the influences which may have existed in humanity during the creation of each work. This paper includes research from books, journals, encyclopedias, and websites which together show similar results, that all things in life travel cycles, and that tendencies and patterns in society will unlikely change fundamentally, although it is hoped that the society will nonetheless evolve for the better. Perhaps the most powerful phenomena which will help people to escape from their sociological problems are music and theatre. Keywords: Musicals, Society,Culture. -

Escinsighteurovision2011guide.Pdf

Table of Contents Foreword 3 Editors Introduction 4 Albania 5 Armenia 7 Austria 9 Azerbaijan 11 Belarus 13 Belgium 15 Bosnia & Herzegovina 17 Bulgaria 19 Croatia 21 Cyprus 23 Denmark 25 Estonia 27 FYR Macedonia 29 Finland 31 France 33 Georgia 35 Germany 37 Greece 39 Hungary 41 Iceland 43 Ireland 45 Israel 47 Italy 49 Latvia 51 Lithuania 53 Malta 55 Moldova 57 Norway 59 Poland 61 Portugal 63 Romania 65 Russia 67 San Marino 69 Serbia 71 Slovakia 73 Slovenia 75 Spain 77 Sweden 79 Switzerland 81 The Netherlands 83 Turkey 85 Ukraine 87 United Kingdom 89 ESC Insight – 2011 Eurovision Info Book Page 2 of 90 Foreword Willkommen nach Düsseldorf! Fifty-four years after Germany played host to the second ever Eurovision Song Contest, the musical jamboree comes to Düsseldorf this May. It’s a very different world since ARD staged the show in 1957 with just 10 nations in a small TV studio in Frankfurt. This year, a record 43 countries will take part in the three shows, with a potential audience of 35,000 live in the Esprit Arena. All 10 nations from 1957 will be on show in Germany, but only two of their languages survive. The creaky phone lines that provided the results from the 100 judges have been superseded by state of the art, pan-continental technology that involves all the 125 million viewers watching at home. It’s a very different show indeed. Back in 1957, Lys Assia attempted to defend her Eurovision crown and this year Germany’s Lena will become the third artist taking a crack at the same challenge. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 25/10/2018 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 25/10/2018 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Wannabe - Spice Girls Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond Zombie - The Cranberries I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor Don't Stop Believing - Journey Dancing Queen - ABBA Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses Perfect - Ed Sheeran Piano Man - Billy Joel Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Africa - Toto Always On My Mind - Willie Nelson Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Black Velvet - Alannah Myles Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Santeria - Sublime Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Someone Like You - Adele Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Valerie - Amy Winehouse Livin' On A Prayer - Bon Jovi Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker New York, New York - Frank Sinatra Girl Crush - Little Big Town House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals What A Wonderful World - Louis Armstrong Summer Nights - Grease Jackson - Johnny Cash Jolene - Dolly Parton Crazy - Patsy Cline Let It Go - Idina Menzel (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding My Girl - The Temptations All Of Me - John Legend I Wanna Dance With Somebody - Whitney Houston Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Turn The Page - Bob Seger Neon Moon - Brooks & Dunn My Way - Frank Sinatra These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Strawberry Wine - Deana Carter I Want It That Way - Backstreet -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 08/11/2017 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 08/11/2017 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Shape of You - Ed Sheeran Someone Like You - Adele Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond Piano Man - Billy Joel At Last - Etta James Don't Stop Believing - Journey Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Wannabe - Spice Girls Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Black Velvet - Alannah Myles Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Jackson - Johnny Cash Free Fallin' - Tom Petty Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Look What You Made Me Do - Taylor Swift I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Girl Crush - Little Big Town House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals Body Like a Back Road - Sam Hunt Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Santeria - Sublime Summer Nights - Grease Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Unchained Melody - The Righteous Brothers Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Turn The Page - Bob Seger Zombie - The Cranberries Crazy - Patsy Cline Thinking Out Loud - Ed Sheeran Kryptonite - 3 Doors Down My Girl - The Temptations Despacito (Remix) - Luis Fonsi Always On My Mind - Willie Nelson Let It Go - Idina Menzel Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor Monster Mash - Bobby Boris Pickett Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Love Shack - The B-52's My Way - Frank Sinatra In Case You Didn't Know - Brett Young Rolling In The Deep - Adele All Of Me - John Legend These -

Transnational Injustices National Security Transfers and International

ISBN 978-92-9037-253-0 Transnational Injustices National Security Transfers and International Law Transnational Injustices Transnational Law and International National Security Transfers ICJ Commission Members September 2017 (for an updated list, please visit www.icj.org/commission) Composed of 60 eminent judges and lawyers from all regions of the world, the International Commission of Jurists promotes Acting President: and protects human rights through the Rule of Law, by using Prof. Robert Goldman, United States its unique legal expertise to develop and strengthen national and international justice systems. Vice-President: Established in 1952 and active on the fi ve continents, the ICJ Justice Michèle Rivet, Canada aims to ensure the progressive development and eff ective implementation of international human rights and international Executive Committee: humanitarian law; secure the realization of civil, cultural, economic, Prof. Carlos Ayala, Venezuela political and social rights; safeguard the separation of powers; Justice Azhar Cachalia, South Africa and guarantee the independence of the judiciary and legal Prof. Andrew Clapham, UK profession. Ms Imrana Jalal, Fiji Ms Hina Jilani, Pakistan Justice Radmila Dragicevic-Dicic, Serbia ® Transnational Injustices: National Security Transfers and Mr Belisário dos Santos Júnior, Brazil International Law Other Commission Members: © Copyright International Commission of Jurists Prof. Kyong-Wahn Ahn, Republic of Korea Justice José Antonio Martín Pallín, Spain Justice Adolfo Azcuna, Philippines