EXPLORING a SHARED HISTORY: Indian-White Relations Between

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

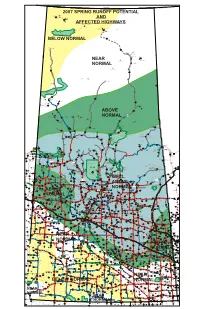

Spring Runoff Highway Map.Pdf

NUNAVUT TERRITORY MANITOBA NORTHWEST TERRITORIES 2007 SPRING RUNOFF POTENTIAL Waterloo Lake (Northernmost Settlement) Camsell Portage .3 999 White Lake Dam AND Uranium City 11 10 962 19 AFFECTEDIR 229 Fond du Lac HIGHWAYS Fond-du-Lac IR 227 Fond du Lac IR 225 IR 228 Fond du Lac Black Lake IR 224 IR 233 Fond du Lac Black Lake Stony Rapids IR 226 Stony Lake Black Lake 905 IR 232 17 IR 231 Fond du Lac Black Lake Fond du Lac ATHABASCA SAND DUNES PROVINCIAL WILDERNESS PARK BELOW NORMAL 905 Cluff Lake Mine 905 Midwest Mine Eagle Point Mine Points North Landing McClean Lake Mine 33 Rabbit Lake Mine IR 220 Hatchet Lake 7 995 3 3 NEAR Wollaston Lake Cigar Lake Mine 52 NORMAL Wollaston Lake Landing 160 McArthur River Mine 955 905 S e m 38 c h u k IR 192G English River Cree Lake Key Lake Mine Descharme Lake 2 Kinoosao T 74 994 r a i l CLEARWATER RIVER PROVINCIAL PARK 85 955 75 IR 222 La Loche 914 La Loche West La Loche Turnor Lake IR 193B 905 10 Birch Narrows 5 Black Point 6 IR 221 33 909 La Loche Southend IR 200 Peter 221 Ballantyne Cree Garson Lake 49 956 4 30 Bear Creek 22 Whitesand Dam IR 193A 102 155 Birch Narrows Brabant Lake IR 223 La Loche ABOVE 60 Landing Michel 20 CANAM IR 192D HIGHWAY Dillon IR 192C IR 194 English River Dipper Lake 110 IR 193 Buffalo English River McLennan Lake 6 Birch Narrows Patuanak NORMAL River Dene Buffalo Narrows Primeau LakeIR 192B St.George's Hill 3 IR 192F English River English River IR 192A English River 11 Elak Dase 102 925 Laonil Lake / Seabee Mine 53 11 33 6 IR 219 Lac la Ronge 92 Missinipe Grandmother’s -

Sask Gazette, Part I, Jun 6, 2008

THIS ISSUE HAS NO PART II (REVISED REGULATIONS) or PART III (REGULATIONS)/ CE NUMÉRO NE CONTIENT PAS DE PARTIE II (RÈGLEMENTS RÉVISÉS) OU DE PARTIE III (RÈGLEMENTS)THE SASKATCHEWAN GAZETTE, JUNE 6, 2008 1055 The Saskatchewan Gazette PUBLISHED WEEKLY BY AUTHORITY OF THE QUEEN’S PRINTER/PUBLIÉE CHAQUE SEMAINE SOUS L’AUTORITÉ DE L’IMPRIMEUR DE LA REINE PART I/PARTIE I Volume 104 REGINA, FRIDAY, JUNE 6, 2008/REGINA, VENDREDI, 6 JUIN 2008 No. 23/nº 23 TABLE OF CONTENTS/TABLE DES MATIÈRES PART I/PARTIE I SPECIAL DAYS/JOURS SPÉCIAUX .................................................................................................................................................. 1056 PROGRESS OF BILLS/RAPPORT SUR L’ÉTAT DES PROJETS DE LOIS (First Session,Twenty-sixth Legislative Assembly) ............................................................................................................................ 1056 ACTS NOT YET PROCLAIMED/LOIS NON ENCORE PROCLAMÉES ..................................................................................... 1056 ACTS IN FORCE ON ASSENT/LOIS ENTRANT EN VIGUEUR SUR SANCTION .................................................................. 1059 ACTS IN FORCE ON SPECIFIC DATES/LOIS EN VIGUEUR À DES DATES PRÉCISES ................................................... 1061 ACTS IN FORCE ON SPECIFIC EVENTS/LOIS ENTRANT EN VIGUEUR À DES OCCURRENCES PARTICULIÈRES ...... 1061 ACTS PROCLAIMED/LOIS PROCLAMÉES (2008) ........................................................................................................................ -

Holy Eucharist 11:30AM Laniwci-Church Divine Liturgy & Cemetery Blessings 1

UPCOMING LITURGIES & EVENTS: June 23-June 30, 2019 WELCOME TO ALL PARISHIONERS, GUESTS AND VISITORS! Date Time Location Event Divine Liturgy: For Our Parishioners, followed by pre-summer 9:30AM Dormition-Church BBQ COMMUNITY NEWS Sun, 23 June Holy Eucharist 11:30AM Laniwci-Church Divine Liturgy & Cemetery Blessings 1. The Shrine of the Venerable Nun Martyrs Olympia and Laurentia (215 Avenue M South) celebrates a Weekly Moleben Service every Sunday evening at 7:00 p.m., followed by fellowship. 3:30PM Hillcrest Cemetery Cemetery Blessings 2. Celebrating the 60th Anniversary of Priesthood for Bishop Emeritus Michael Wiwchar, 7:00PM Dormition-Church Divine Liturgy: Health-Andrij Shchavii (SSMI-Saskatoon) Tues, 25 June CSsR Sunday, July 7th, at the Ukrainian Catholic Cathedral of St. George (210 Avenue M South 7:30PM Dormition-Auditorium Executive Meeting Saskatoon). Moleben Service at 5:00 pm ~ Cocktails and Banquet to follow ~ St. George's Thurs, 27 June 6:00PM Martyr’s Shrine Feast Day Celebrations Auditorium. Tickets: Adults: $30 ~ Youth (12-18): $20 ~ Children (5-11): $10 ~ Under 4 - free Limited Number of tickets will be available, so get your tickets early! Tickets will be available starting Sat, 29 June 10:00AM Ss. Peter & Paul Parish Feast Day Divine Liturgy Ss Peter & Paul on May 26th. Deadline for Tickets is Tuesday, July 2nd! For more information contact: Andrea Sun, 30 June 9:30AM Dormition-Church Divine Liturgy: For Our Parishioners Wasylow at 306-230-1659 – email [email protected]. Sponsored by the Eparchial Pastoral Christ, Lover of Council. Mankind 11:30AM Bodnari-Church Feast Day Liturgy & Cemetery Blessings th 3. -

Directory of Communities

ELECTIONS SASKATCHEWAN Directory of Communities April 2014 OFFICE OF THE CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER (ELECTIONS SASKATCHEWAN) 1702 PARK STREET, REGINA, SASKATCHEWAN CANADA S4N 6B2 TELEPHONE: (306) 787-4000 / 1-877-958-8683 FACSIMILE: (306) 787-4052 / 1-866-678-4052 WEB SITE: www.elections.sk.ca ISBN 978-0-9921510-4-1 Directory of Communities TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 2 Section 1: Provincial Constituency by Urban Municipality 4 Section 2: Urban Municipality by Provincial Constituency 29 Section 3: Urban Municipality by Federal Electoral District 56 Section 4: Provincial Constituency Maps 80 Section 5: Federal Electoral District Maps 143 1 Introduction Directory of Communities Introduction Saskatchewan’s cities are governed by The Cities Act, while the remaining urban municipalities are governed In Saskatchewan, there are electoral boundaries by The Municipalities Act. A municipality is created by a designed for three levels of government: federal, ministerial order that describes its boundaries.” provincial and municipal. New Provincial Constituencies Elections Saskatchewan (referred to in legislation as “The Office of the Chief Electoral Officer”) is the province’s Statistics Canada compiles a census of population in independent, impartial election management body. each province. The most recent census was done in 2011. With a legal mandate established by the Legislative In Saskatchewan, a Constituency Boundaries Commission is Assembly of Saskatchewan, it plans, organizes, conducts established in accordance with The Constituency Boundaries and reports on provincial electoral events. Act, 1993, following each census taken every tenth year after 1991. Accordingly, a boundary review for Saskatchewan was While Elections Saskatchewan is not responsible for conducted in 2012. federal and municipal electoral events, it seeks to collaborate and work closely with the bodies responsible The Saskatchewan Provincial Constituency Boundaries for conducting those events. -

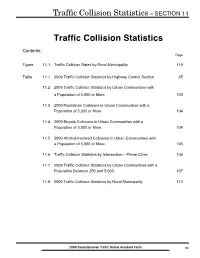

Traffic Collision Statistics– SECTION 11

Traffic Collision Statistics – SECTION 11 Traffic Collision Statistics Contents: Page Figure 11.1 Traffic Collision Rates by Rural Municipality 119 Table 11.1 2009 Traffic Collision Statistics by Highway Control Section 85 11.2 2009 Traffic Collision Statistics by Urban Communities with a Population of 5,000 or More 103 11.3 2009 Pedestrian Collisions in Urban Communities with a Population of 5,000 or More 104 11.4 2009 Bicycle Collisions in Urban Communities with a Population of 5,000 or More 104 11.5 2009 Alcohol-Involved Collisions in Urban Communities with a Population of 5,000 or More 105 11.6 Traffic Collision Statistics by Intersection – Three Cities 106 11.7 2009 Traffic Collision Statistics by Urban Communities with a Population Between 250 and 5,000 107 11.8 2009 Traffic Collision Statistics by Rural Municipality 112 2009 Saskatchewan Traffic Safety Accident Facts 83 Traffic Collision Statistics – SECTION 11 Traffic Collision Statistics Table 11.1 is a detailed summary of all provincial highways in the province. The length of each section of highway, along with the average daily traffic (ADT) on that section, is used to calculate travel (kilometres in millions) and a collision rate (collisions per million vehicle kilometres) for each section. Tables 11.2 and 11.3 summarize collisions by community, and Table 11.8 shows a similar summary by rural municipality. Collision rates are calculated based on populations, as well as travel, where applicable. 2009 Quick Facts: • The collision rate for all provincial highways is 1.54 collisions per million vehicle kilometres (Mvkm). • The average number of collisions per 100 people for communities with a population: - of 5,000 or more is 5.00 - of 250 to 4,999 is 1.29 - under 250 is 0.66 • Regina and Saskatoon combined account for 40% of the province’s population and 44% of the collisions. -

Travel Guide

Dedication This project is dedicated to the memory of the Ukrainian pioneer children. Edmore – Dormition of the Blessed Mother of God Old homestead near Jasmin National Home Brooksby – St. Nicholas Memorial between Alvena and Cudworth Acknowledgments The Saskatchewan Ukrainian Historical Society, a project of donated their talents on many levels throughout this project. the Ukrainian Canadian Congress – Saskatchewan Provincial The spirit of our ancestors in preserving our heritage shines Council, would like to thank the many people who have as- through these individuals. sisted the committee in researching this project. Their gener- The photographers, map designer and travel guide de- osity of time was shared by touring us through the country signer’s creative and artistic eye is reflective of the vibrant side, unlocking the doors of their parishes, sharing their com- culture in this province. The creative team: Rosemarie Gray, munity history, giving excellent road directions and respond- Don Skopyk, Ken Mazur, Michael Horbay, Izaiah Pidskalny, ing to our requests to share with the world our rich Sas- and Karen Pidskalny. katchewan Ukrainian heritage. The Saskatchewan Ukrainian Historical Society commit- Karen Pidskalny tee of Rosemarie Gray, Ken Mazur, and Don Skopyk has Project Coordinator © 2006 by the Saskatchewan Ukrainian Historical Society Saskatchewan’s Ukrainian Legacy 1 Contents Sources Introduction .............................................................................2 Ukrainian Catholic The six Ukrainian ethnic bloc -

Saskatchewan Tire Collection Zones

Legend Saskatchewan 0255075 Tire Zones First Nation Reserve Highway Kilometres Tire Collection Zones Urban Municipality Park R.M. Water Creation Date 01/13/2018 Version 1.0 Mahigan UV165 Oskikebuk Lake MISTIK 184 106 Lake 203 UV Map 1 of 1 WASKWAYNIKAPIK Lake Vance 228 Wildfong Annabel 919 Dore Lake Bryans Lake UV Casat 911 Lake UVViney Lake Lake Lake Lake NAKISKATOWANEEK 227 Neagle FLIN FLON 165 Lake UV CREIGHTON Flotten UV903 Sarginson MCKAY IM Lake Lake 209 PISIWIMINIWAT Hanson Smoothstone 207 Lake Lake Deschambault NARE BEACH DORE 106 DE Waterhen LAK 912 MUSKWAMINIWATIM Lake UV E UV Chisholm Spectral 924 Limestone Shuttleworth UV 225 Lake UV2 Lake Lake Lake McNally Lake W ATERHEN UV969 AMISK Lake Hollingdale 130 Stringer LAKE M Beaupre 916 Lake EADOW UV Lake 184 BI LA Lake Molanosa Cobb Kerr G KE GREIG L 167 IS AKE UV 21 LAND PROVINCIA UV155 Lake Lake Hobbs Lake Amisk UV G L SO OO UT PIE DSOIL H Sled Clarke Lake Lake Nepe RCELA PAR WATERH GLADUE Edgelow ND K EN Lake Lake Oatway Balsam Lake LAKE LAKE Lake Meeyomoot Shallow Renown Lake Lake Maraiche 105 SLED Lake UV55 Nipekamew Lake Lake Lake DORIN L Lake Saskoba 622 TOSH AKE Lake WEYAKWIN Big Sandy Harrington AMISKOSAKAHIKAN Wanner Lake Narrow Herman Lake 210 Lake Lake Goulden Lake Lake UV924 East Trout Saunders GRE Lake Lake Suggi Windy EN Montre 26 4 al 927 UV106 Lake Lake UV UV LAK Lake UV Little Bear E Lake Leonard STURGEON WEIR Marquis Lake 184 Lake Red Bobs T 55 CLARENCE-STEEPBANK Waterfall HUNDERCHILD FLYING DUST UV Lake O'Leary Lake 115 UV55 105 LAKES PROVINCIAL PARK Lake Namew -

Provincial Composite

0 25 50 75 Saskatchewan S E Kilometres I Provincial C N Creation Date E E Electoral U C 01/10/2020 T I N Legend Version 1.3 I COMPOSITE Constituency T V S ² O N Constituency First Nation Reserve Highway R O P C This map is a graphic representation of N F Saskatchewan provincial constituencies to be I Urban Municipality Park Saskatchewan constituency boundaries are drawn in accordance with The represented by elected members of the O Representation Act, 2012 and any amendments thereto. These maps have been H Legislative Assembly of Saskatchewan. The produced solely for the purpose of identifying polling divisions within each constituency. T N I Water boundaries of these constituencies are for the O Source data has been adapted from Information Services Corporation of Saskatchewan, W I 28th and 29th General Election. Provincial Sask Cadastral (Surface) dataset and administrative overlays. Reproduced with the T permission of Information Services Corporation of Saskatchewan. A C All data captured on this map is current as of the retrieval date of January 2019, unless otherwise stated. Composite O L Map 1 of 1 110°W 109° W 108°W 102°W 107°W 106°W 105°W 104°W 103°W s Dionne Collins Hatle Combre Thainka Scott Lake Ena Selwyn Lake Lake Lake Lake ake Lake Sovereign L Lake Hamill Lake isaw Picea Robins Alley Lake M Lake Lake Lake Lake Wayow Gebhard Lake Lake Bailey Tazin Premier Hamden Lake Lake Lake Lake Saruk Patterson Tsalwor Dodge Lake Lake Lake Lake Polgreen Lake Anson Middlemiss Lake Keseechewun Harper Taché Lake Many Islands Oldman Bonokoski -

Ministry of Social Services

Directory - Serving Communities Ministry of Social Services saskatchewan.ca | Revised: August 2019 Table of Contents How to Use this Directory ............................................................................................................................4 Service Centres - Office Addresses and Telephone Numbers ...............................................5 Directory of Communities and Office Code .....................................................................................6 How to Use this Directory This directory identifies which Service Centre serves each Saskatchewan community. Simply: 1. Look up the community in question and identify the office code for that community. 2. Identify the office by using the key below. 3. Refer to the list of offices, addresses and telephone numbers listed on next page. 4. The public can write or telephone their local office. KEY: BN ........ BUFFALO NARROWS MJ ......... MOOSE JAW CR ......... CREIGHTON NI ......... NIPAWIN ES ......... ESTEVAN NB ......... NORTH BATTLEFORD FQ ......... FORT QU’APPELLE PA ......... PRINCE ALBERT Kl ........... KINDERSLEY RE ......... REGINA LO ......... LA LOCHE RO ......... ROSETOWN LR .......... LA RONGE SA ......... SASKATOON LL .......... LLOYDMINSTER SC ......... SWIFT CURRENT ML ........ MEADOW LAKE WBN ..... WEYBURN ME ........ MELFORT YO ......... YORKTON 4 | Serving Communities | Ministry of Social Services Service Centres Buffalo Narrows 1-800-667-7685 Moose Jaw (306) 694-3647 Box 220, 310 Davey Street Fax (306) 235-1794 36 Athabasca -

Sask Gazette, Part I, Feb 23, 2007

THIS ISSUE HAS NO PART III (REGULATIONS) THE SASKATCHEWAN GAZETTE, FEBRUARY 23, 2007 201 The Saskatchewan Gazette PUBLISHED WEEKLY BY AUTHORITY OF THE QUEEN’S PRINTER/PUBLIÉE CHAQUE SEMAINE SOUS L’AUTORITÉ DE L’IMPRIMEUR DE LA REINE PART I/PARTIE I Volume 103 REGINA, FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 23, 2007/REGINA, VENDREDI, 23 FÉVRIER 2007 No. 8/nº 8 TABLE OF CONTENTS/TABLE DES MATIÈRES PART I/PARTIE I SPECIAL DAYS/JOURS SPÉCIAUX .............................. 202 The Business Names Registration Act ................................. 213 PROGRESS OF BILLS/RAPPORT SUR L’ÉTAT The Non-profit Corporations Act, 1995/ DES PROJETS DE LOIS (2006-2007) .......................... 202 Loi de 1995 sur les sociétés sans but lucratif ................... 223 ACTS NOT YET PROCLAIMED/ PUBLIC NOTICES/AVIS PUBLICS ............................... 224 LOIS NON ENCORE PROCLAMÉES ......................... 202 The Change of Name Act, 1995/ Loi de 1995 sur le changement de nom............................. 224 ACTS IN FORCE ON ASSENT/LOIS The Crown Minerals Act ....................................................... 226 ENTRANT EN VIGUEUR SUR SANCTION .............. 204 Highway Traffic Board .......................................................... 226 ACTS IN FORCE ON SPECIFIC DATES/LOIS The Municipalities Act .......................................................... 227 EN VIGUEUR À DES DATES PRÉCISES ................ 204 The Real Estate Act ............................................................... 227 ACTS IN FORCE ON SPECIFIC EVENTS/ The Saskatchewan Insurance Act -

Directory of Communities Ministry of Social Services

Directory of Communities Ministry of Social Services saskatchewan.ca | 06/13 | SAP-1 Table of Contents How to Use the Directory of Office Key............................................................................................... 4 Office Addresses and Telephone Numbers - Service Centres ...............................................5 Directory of Communities and Office Code .....................................................................................6 How to Use the Directory of Office Key This directory identifies which Service Centre serves each Saskatchewan community. Simply: 1. look up the community in question and identify the office code for that community 2. identify the office, using the key below 3. refer to the list of offices, addresses and telephone numbers (page 5) 4. the public can write or telephone their local office KEY: BN ........ BUFFALO NARROWS ML ........ MEADOW LAKE CR ......... CREIGHTON NB ......... NORTH BATTLEFORD ES ......... ESTEVAN NI ......... NIPAWIN FQ ......... FORT QU’APPELLE PA ......... PRINCE ALBERT Kl ........... KINDERSLE RE ......... REGINA LL .......... LLOYDMINSTER RO ......... ROSETOWN LO ......... LA LOCHE SA ......... SASKATOON LR .......... LA RONGE SC ......... SWIFT CURRENT ME ........ MELFORT WBN ..... WEYBURN MJ ......... MOOSE JAW YO ......... YORKTON 4 | Directory of Communities | Ministry of Social Services Service Centres Buffalo Narrows Service Centre ...........Toll Free 1-800-667-7685 Nipawin Service Centre ...............................Toll Free 1-800-487-8594 -

Regional Health Authority Community List

Place Name Health Region Abbey Cypress Abbott Sun Country Aberdeen Saskatoon Aberfeldy Prairie North Abernethy Regina Qu'Appelle Abound Five Hills Ada Five Hills Adams Regina Qu'Appelle Adanac Heartland Admiral Cypress Aikins Cypress Air Ronge Mamawetan Churchill River Akosane Kelsey Trail Alameda Sun Country Albatross Regina Qu'Appelle Albertville Prince Albert Parkland Aldina Prince Albert Parkland Algrove Kelsey Trail Alice Beach Regina Qu'Appelle Alida Sun Country Allan Saskatoon Allan Hills Saskatoon Alsask Heartland Alta Vista Regina Qu'Appelle Altawan Cypress Alticane Prince Albert Parkland Alvena Saskatoon Amazon Saskatoon Ambassador Saskatoon Amiens Prince Albert Parkland Amsterdam Sunrise Amulet Sun Country Ancrum Saskatoon Anerley Heartland Aneroid Cypress Anglia Heartland Anglin Lake Prince Albert Parkland Annaheim Saskatoon Antelope Cypress Antler Sun Country Aquadell Five Hills Aquadeo Prairie North Aquadeo Beach Prairie North Arabella Sunrise Arborfield Kelsey Trail Arbury Regina Qu'Appelle Arbuthnot Five Hills Archerwill Kelsey Trail Archive Five Hills Archydal Five Hills Place Name Health Region Arcola Sun Country Ardath Heartland Ardill Five Hills Ardwick Five Hills Arelee Heartland Argo Heartland Arlington Beach Saskatoon Arma Saskatoon Armilla Sun Country Armit Kelsey Trail Armley Kelsey Trail Armour Regina Qu'Appelle Arpiers Saskatoon Arran Sunrise Artland Prairie North Aspen Cove Prairie North Asquith Saskatoon Assiniboia Five Hills Attica Saskatoon Atwater Sunrise Auburnton Sun Country Ava Heartland Avebury Prince