Lifting the Domestic Veil: the Challenges of Exporting Differentiated Goods Across the Development Divide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wines by the Glass Champagne & Sparkling Chardonnay Sauvignon Blanc Pinot Grigio & Pinot Gris Interesting Whites Caberne

Wine Feature Mohua Sauvignon Blanc, Marlborough, 2015 Ripe and juicy tropical fruits, rich stone fruit and fresh cut lime combined with notes of fresh picked summer herbs. glass 12 bottle 47 champagne & sparkling cabernet sauvignon & blends Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin, Brut Reims NV 120 Caymus Vineyards Napa Valley 2013 150 Domaine Chandon, Blanc de Noirs Carneros NV 50 Alexander Valley Vineyards Alexander Valley 2013 55 Moët & Chandon, Imperial Épernay NV 105 Jordan Alexander Valley 2012 119 Moët & Chandon, Dom Pérignon Épernay 2003 275 Silver Oak Alexander Valley 2011 149 Santa Margherita, Prosecco Brut Italy NV 54 Caymus, Special Selection Napa Valley 2013 250 Taittinger Comtes de Champagne France 2000 395 Nickel & Nickel, Sullenger Vineyard Oakville 2013 165 Cakebread Cellars Napa Valley 2012 149 chardonnay William Hill Napa Valley 2012 80 Jordan Russian River Valley 2013 75 Estancia Meritage Paso Robles 2013 72 Sonoma-Cutrer Russian River Valley 2014 59 Red Diamond California 2012 31 Ferrari-Carano Alexander Valley 2014 70 Quintessa Rutherford 2011 205 Grgich Hills Napa Valley 2012 110 Opus One Napa Valley 2012 295 Lindeman’s Bin 65 Australia 2015 27 Hogue Cellars Columbia Valley 2014 28 Cakebread Cellars Napa Valley 2013 95 Louis M. Martini Napa Valley 2012 52 Far Niente Napa Valley 2014 120 J. Lohr Hilltop Vineyard Paso Robles 2013 70 Kistler ‘Les Noisetiers’ Sonoma County 2014 145 Cryptic Red California 2012 39 Stags’ Leap Winery Stags Leap District 2013 72 Louis Latour Meursault 2013 115 J. Lohr ‘Seven Oaks’ Paso Robles 2013 43 Louis Latour Puligny-Montrachet 2013 125 Murphy-Goode ‘Homefront Red’ Blend California 2012 39 Casa Lapostolle Casablanca Vineyard 2013 39 Concha Y Toro ‘Gran Reserva’ Chile 2013 43 Chateau Ste. -

WINE LIST Gl / Btl HOUSE Canyon Road / Vista Point - Chardonnay, Pinot Grigio, Pinot Noir, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot 6 / 20

WINE LIST gl / btl HOUSE Canyon Road / Vista Point - Chardonnay, Pinot Grigio, Pinot Noir, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot 6 / 20 BUBBLES gl / btl ROSE gl / btl Lamarca, Prosecco, split, Italy 12 La Vieille Ferme, Rose, Rhone Valley, France 8 / 30 J. Roget, Brut, American Champagne, New York 6 / 20 Chloe, Rose, Central Coast, California 9 / 35 Campo Viejo, Cava Brut Rose, Sparkling Wine, Spain 8 / 30 Del Rio Estate, Grenache Rose, Rogue Valley, Oregon 38 G.H. Mumm, Grand Cordon Brut, Champagne, France 75 Daou, Rose, Paso Robles, California 45 WHITES gl / btl REDS gl / btl William Hill, Chardonnay, Central Coast, California 9 / 35 Cannonball, Cabernet Sauvignon, Healdsburg, California 9 / 35 Acrobat, Chardonnay, Eugene, Oregon 10 / 38 Freak Show, Cabernet Sauvignon, Graton, California 12 / 45 Buehler, Chardonnay, Russian River Valley, California 12 / 45 Del Rio, Cabernet Sauvignon, Rogue Valley, Oregon 50 Annabella, Chardonnay, Napa Valley, California 35 Substance, Cabernet Sauvignon, Benton City, Washington 60 Cave de Lugny, Chardonnay, Macon-Lugny, France 40 Kenwood, Cabernet Sauvignon, Sonoma Mountain, California 75 Walt, Chardonnay, Sonoma Coast, California 75 Arrowood, Cabernet Sauvignon, Knights Valley, Sonoma, California 90 Grounded, Sauvignon Blanc, Hopland, California 9 / 35 Stemmari, Pinot Noir, sustainable, Sicily, Italy 9 / 35 Oyster Bay, Sauvignon Blanc, Marlborough, New Zealand 10 / 38 Meiomi, Pinot Noir, tri-county Coastal, California 12 / 45 Los Cardos, Sauvignon Blanc, Mendoza, Argentina 30 Montinore Estate, Pinot Noir, Willamette -

Duval's Retail Wines

Duval’s Retail Wines Exceptional Value Whites Veuve du Vernay – Split - Brut Sparkling – France 6 Valdo – Split - Brut Prosecco – Italy 5 Beringer White Zinfandel – CA 8 Vie Vité Rosé – Côtes de Provence, France 19 Essence Riesling – Mosel, Germany 17 Moonlight White Blend – Tuscany, Italy 17 Benvolio Pinot Grigio – Friuli, Italy 10 La Crema Pinot Gris – Monterey, CA 10 Justin Sauvignon Blanc – Paso Robles, CA 14 Dog Point Vineyard Sauvignon Blanc – Marlborough, New Zealand 17 Parducci Chardonnay – Mendocino, CA 11 Cambria “Benchbreak Vineyard” Chardonnay – Santa Maria Valley, CA 13.5 Trefethen Chardonnay – Oak Knoll, Napa Valley, CA 19 Exceptional Value Reds Steelhead Pinot Noir – Sonoma, CA 13 Acrobat Pinot Noir – Oregon 18 Meiomi Pinot Noir – Sonoma, CA 16.5 Collina Chianti – Tuscany, Italy 10 Santa Ema Merlot – Chile 17.5 Michel Torino “Colección” Malbec – Calchaquí Valley, Argentina 17 Brazin “Old Vine” Zinfandel – Lodi, CA 13.5 Trapiche “Broquel” Malbec – Mendoza, Argentina 15 Wente S. Hill Cabernet Sauvignon – Livermore Valley, CA 14 One Hope Cabernet Sauvignon - CA 13 Uppercut Cabernet Sauvignon – California 19 Robert Mondavi Cabernet Sauvignon – Napa Valley, CA 23.5 Champagne & Sparkling Wines Valdo Brut DOC Prosecco – Valdobiaddene, Italy 16 Segura Viudas Brut Reserva Cava – Spain 14 Roederer Estate Brut Rosé Sparkling – Anderson Valley, CA 33 Argyle Brut Sparkling – Willamette Valley, Oregon 23 Veuve Cliquot “Yellow Label” Brut – Champagne, France 76.5 Laurent-Perrier Brut Cuvée Rosé – Champagne, France 63 Light To Medium-Bodied -

House Wines by the Glass $7

Rick’s Club American House Wines by the Glass $7. Yellow Tail (Australia) Chardonnay · Cabernet Sauvignon · Merlot · Pinot Noir · Shiraz Trapiche Malbec (Argentina) Cavit “Lunetta” Prosecco (Italy) Placido Pinot Grigio (Italy) Vendange White Zinfandel (California) White Wines By the Bottle Glass Bottle Kendall Jackson "Grand Estate" Chardonnay 8. 28. (California) A well balanced and medium bodied wine with lemon-lime on the nose and flavors of pear and green apple. Francis Ford Coppola "Diamond Collection" 7.5 25. Chardonnay (California) Light creamy texture with a hint of Creme Brulee from the oak; fragrant flavors of tropical fruits, apples and pears. Barone Fini Pinot Grigio (Italy) 22. Flavors of ripe peaches and fresh clean fruit. Balanced with a layer of acidity and vibrant white currants. Domino Moscato (California) 7. 22. Citrus and floral notes with honey, nectarine and tropical fruit. Blue Fish Sweet Riesling (Germany) 7. 26. Fruity sweetness with a full-bodied structure and refreshing acidity. Sterling Sauvignon Blanc (California) 7.5 28. Ripe flavors of peach and passion fruit with classic herbaceous Sauvignon Blanc characters. 1200245 Red Wines By the Bottle Glass Bottle Estancia Cabernet Sauvignon (California) 8. 28. Black currant, plum and blackberry flavors with oak notes. Cocoa and mocha tones slide through a harmonious finish. Red Diamond Cabernet Sauvignon (Washington) 8. 28. Red fruit jam and a sweet touch of toasty oak on the long finish. Trapiche Malbec (Argentina) 7. 22. Jammy cherry aromas with mocha hints; medium bodied with bright acidity and cherry, mint and leather flavours on the medium finish. Red Diamond Merlot (Washington) 8. -

Wine & Spirits

WINE & SPIRITS “VINO DA TAVOLA” HOUSE WINES WHITE WINE CRAFT COCKTAILS SPECIALLY SELECTED BY BY THE BOTTLE OUR SOMMELIER LA DOLCE VITA ........................... 14 SPARKLING & ROSÉ tito’s vodka, fresh citrus, peach purée WINE COTE DES ROSES ROSÉ (FRANCE) .........................48 BROOKLYN BORN ........................ 14 BY THE GLASS CAPOSALDO PROSECCO DOC (ITALY) ................... 35 knob creek bourbon, blood orange MIONETTO PROSECCO (187ML) ...... 13 & basil muddle, orange bitters (ITALY) PINOT GRIGIO IL VINCE DOC (VENEZIE) ...................................... 35 FIGURA LEMON DROP .................. 14 MIONETTO MOSCATO (187ML) ........ 13 MONTASOLO (VENETO) ........................................39 fig infused vodka, vanilla, fresh citrus (ITALY) BANFI SAN ANGELO (TUSCANY) ............................ 42 IAVARONE OLD FASHIONED ........ 14 PINOT GRIGIO .............................. 12 SANTA MARGHERITA (ITALY) ................................ 62 woodford reserve bourbon, (ITALY) orange bitters, amaro CHARDONNAY ..................... 12 SAUVIGNON BLANC NOBLE VINES 446 (CALIFORNIA) ...........................39 CLASSIC NEGRONI ....................... 14 (NEW ZEALAND) hendrick's gin, campari, sweet vermouth KENDALL JACKSON (CALIFORNIA) ......................... 42 CHARDONNAY ............................. 12 CHALK HILL SONOMA COAST (CALIFORNIA) ...........45 - MAKE IT A SBAGLIATO- (CALIFORNIA) CAKEBREAD CELLARS (CALIFORNIA) .....................70 made with Prosecco ROSÉ ........................................... 12 SAUVIGNON BLANC -

Villa Sandi Prosecco Valdobbiadene, Italy Pine Ridge Chenin Blanc

WILHELMINA’S WINE SELECTION SPARKLING Villa Sandi Prosecco Valdobbiadene, Italy 12 56 WHITE Pine Ridge Chenin Blanc-Viognier Clarksburg, USA 13 60 Tarani Sauvignon Blanc Lanquedoc, France 12 56 Markus Huber “Terrassen” Grüner Veltliner Traisental, Austria 13 60 Banfi Principessa Gavia Cortese Gavi, Italy 13 60 De Wetshof “Sur Lie” Chardonnay Robertson, South Africa 14 63 Rutherford Ranch Chardonnay Napa Valley, USA 16 72 Domaine William Fevre Chablis Burgundy, France 18 81 Two Vines Riesling Washington State, USA 13 60 ROSÉ AIX Rose de Provence, France 14 63 RED Louis Jadot Pinot Noir Burgundy, France 16 72 Stemmari Nero d’Avola Sicily, Italy 13 60 Decoy by Duckhorn Merlot Sonoma County, USA 17 76 Wilow Bridge Estate “Dragonfly” Shiraz Western Australia 16 72 Famille Jouffreau Clos de Gamot Malbec Cahors, France 14 63 Trapiche Medalla Cabernet Sauvignon Mendoza, Argentina 13 60 Decoy by Duckhorn Cabernet Sauvignon Sonoma County, USA 17 76 Rancho Zabaco Zinfandel Dry Creek Sonoma County, USA 16 72 “Cannot find anything to your liking, please ask for our premium wine list” All prices are in USD and exclude sales tax All wines are served in the proper crystal Riedel glassware WILHELMINA’S UNIQUE BY THE BOTTLE SELECTION CHAMPAGNE & SPARKLING NV Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin Brut Champagne, France 120 NV Laurent Perrier Brut Champagne, France (last btl.) 120 NV Domaine Carneros by Taittinger Rosé Napa Valley, USA 90 SAUVIGNON BLANC 2017 Cloudy Bay Marlborough, New Zealand 115 VIOGNIER 2014 Ogier Condrieu Blanc Rhône Valley, France 99 CHARDONNAY -

Annual Report of the Special Rapporteur

CHAPTER II ASSESSMENT OF THE CURRENT STATE OF FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION IN THE HEMISPHERE A. Introduction. Methodology 1. This Chapter describes certain aspects related to the current state of freedom of expression in the Americas. It includes, as did previous reports, a table summarizing cases in which journalists were murdered in 2002, the circumstances surrounding their deaths, the possible motives of the killers, and the status of investigations. 2. To facilitate the description of the specific situation in each country, the Rapporteur classified the various methods used to curtail the right to freedom of expression and information. All of these methods are incompatible with the Principles on Freedom of Expression adopted by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR). The list includes, in addition to murder, other forms of aggression such as threats, detention, judicial actions, intimidation, censorship, and legislation restricting freedom of expression. The Chapter also includes, for certain countries, positive developments, such as the passing of access to information laws, the abolition of desacato (contempt of authority) in one country of the hemisphere and the existence of bills or judicial decisions conducive to full exercise of freedom of expression. 3. The data in this Chapter correspond to 2002. The Office of the Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression receives information on freedom of expression-related developments from a number of different sources.16 Once the Office has received the information, and bearing in mind the importance of the matter at hand, it begins the verification and analysis process. Once that task is completed, the information is grouped under the aforementioned headings. -

Business INNOVATION and LEARNING DYNAMICS in THE

AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF WINE ECONOMISTS AAWE WORKING PAPER No. 145 Business INNOVATION AND LEARNING DYNAMICS IN THE CHILEAN AND ARGENTINE WINE INDUSTRIES Fulvia Farinelli Dec 2013 www.wine-economics.org ISSN 2166-9112 Innovation and Learning Dynamics in the Chilean and Argentine Wine Industries Fulvia Farinelli *, UNCTAD 1. Introduction This paper focuses on the magnitude, variety, and sources of innovation introduced by the Chilean and Argentine wine industries during the past two decades. It analyzes whether the prolonged export growth of Chilean and Argentine wines has been achieved by building the innovation capacity of local actors and creating domestic linkages with local grape producers, winemakers and input providers, or by relying exclusively upon FDI and knowledge flows generated abroad. In line with the evolutionary tradition, this study explores the hypothesis that, much as in the case of high-tech sectors, the ability of developing countries to enter knowledge-intensive natural resource-based sectors, such as wine, depends on their ability to access capital, technology and knowledge from abroad, that is, on what can be defined as “external” sources of innovation. It also depends, however, on the ability to absorb and adapt imported technology and know-how to the local environment, that is, on the creation of local tacit knowledge and endogenous R&D capabilities. This paper measures, first of all, the innovativeness of the leading 25 Chilean and of the leading 25 Argentine exporters of bottled wines, and looks at the variety of innovations introduced, focusing not only on new methods of production, but also on the development of new products and new ways of organizing business. -

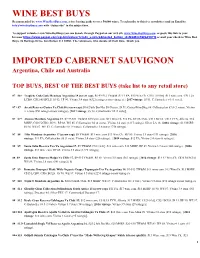

Wine Best Buys Imported Cabernet Sauvignon

WINE BEST BUYS Recommended by www.WineBestBuys.com, a free buying guide to over 50,000 wines. To subscribe to this free newsletter send an Email to [email protected] with “Subscribe” in the subject box. To support volunteer-run WineBestBuys you can donate through Paypal on our web site www.WineBestBuys.com or paste this link to your browser https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr?cmd=_s-xclick&hosted_button_id=MGM4LKWG85KFQ or mail your check to Wine Best Buys, 70 Heritage Drive, San Rafael, CA 94901. The volunteers, who donate all their time, thank you. IMPORTED CABERNET SAUVIGNON Argentina, Chile and Australia TOP BUYS, BEST OF THE BEST BUYS (take list to any retail store) 87 $6+ Trapiche Oak Cask Mendoza Argentina 18 (screw cap). $6.49-$12 TW&M. $7.19 PA. $10 WineCh. C$10.10 SAQ. $11 wine.com. C$11.25 LCBO. C$12.45 BCLS. JS 92. TP 90. Vivino 3.4 stars (6322 ratings across vintages). [2017 vintage: JS 91. Cellartracker 81 (1 vote)]. 87+ $7 Aresti Reserva Curico Va Chile16 (screw cap). $14/2 btls BevMo. $8 Costco. JS 91. CostcoWineBlog 88. Cellartracker 87.8 (3 votes). Vivino 3.3 stars (250 ratings across vintages). [2017 vintage: JS 90. Cellartracker 85 (1 vote)]. 87 $7+ Alamos Mendoza Argentina 17. $7.77-$11 TW&M. $10 wine.com. $11 WineCh. $12 PA. $13 BevMo. C$13 BCLS. C$13 ZYN, Alberta. $14 MSRP. C$16 LCBO. JS 91. RP 88. WS 85. Cellartracker 86 (4 votes). Vivino 3.6 stars (1317 ratings). Silver LA 18. -

Populism in Latin America

Populism in Latin America Oxford Handbooks Online Populism in Latin America Carlos de la Torre The Oxford Handbook of Populism Edited by Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, Paul Taggart, Paulina Ochoa Espejo, and Pierre Ostiguy Print Publication Date: Oct 2017 Subject: Political Science, Political Behavior, Comparative Politics Online Publication Date: Nov 2017 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198803560.013.8 Abstract and Keywords Since the 1930s and 1940s until the present, populist leaders have dominated Latin America’s political landscapes. This chapter explains the commonalities and differences between the different subtypes of Latin American populism—classical, neoliberal, and radical. It examines why these different manifestations of populism emerged, and their democratizing and inclusionary promises while seeking power. Then it analyzes their impact on democracy after gaining office. Whereas populists seeking power promise to include the excluded, once in power populists attacked the institutions of liberal democracy, grabbed power, aimed to control social movements and civil society, and clashed with the privately owned media. Keywords: Latin America, classical populism, neoliberal populism, radical populism, democracy, authoritarianism LATIN America is the land of populism.1 From the 1930s and 1940s until the present, populist leaders have dominated the region’s political landscapes. Mass politics emerged with populist challenges to the rule of elites who used fraud to remain in power. The struggle for free and open elections, and for the incorporation of those excluded from politics, is associated with the names of the leaders of the first wave of populism: Juan and Eva Perón in Argentina, Getulio Vargas in Brazil, Victor Raúl Haya de la Torre in Perú, or José María Velasco Ibarra in Ecuador. -

Wine List Hwouinsee

est 2019 S U D E S T A D A J A K A R T A Wine List HWOUinSeE BY BY BY RED WINE GLASS DECANTER BOTTLLE Terrazas Alto Del Plata Malbec, 2017 200 550 1.000 Grand Albarda Malbec, 2019 150 450 800 Jacob's Creek Shiraz Cabernet, 2018 140 350 650 BY BY BY WHITE WINE GLASS DECANTER BOTTLLE Grand Albarda Chardonnay, 2017/2018 150 400 750 Don Alejandro Sauvignon Blanc, 2019 140 350 650 BY BY BY SWEET WINE GLASS DECANTER BOTTLLE Lindeman's Bin 90 Moscato 140 400 700 *All prices are in thousand rupiah and subject to government tax and service charge Argentina MENDOZA RED WINE Kaiken Ultra Malbec, 2017 1.300 Zuccardi Seri Q Malbec, 2017 1.200 Trapiche Medalla Malbec, 2016 1.100 Santa Julia Del Mercado Malbec, 2018 950 Norton Reserva Malbec, 2016 900 Zuccardi Seri A Bonarda, 2018 850 Trapiche Finca Las Palmas Cabernet Sauvignon, 2017 850 WHITE WINE Trapiche Medalla Chardonnay, 2016 1.000 Trapiche Finca Las Palmas Chardonnay, 2016 800 *All prices are in thousand rupiah and subject to government tax and service charge Argentina SAN JUAN RED WINE Finca Las Moras Barel Select Malbec, 2019 900 Finca Las Moras Malbec, 2020 700 WHITE WINE Finca Las Moras Chardonnay, 2020 700 *All prices are in thousand rupiah and subject to government tax and service charge Spain RED WINE Marques De Riscal Gran Reserva Rioja Tempranillo, 2007 2.550 Vina Pomal Crianza Rioja Tempranillo, 2015 950 Torres Coronas Penedes Tempranillo, 2015 750 WHITE WINE Vina Sol Torres Penedes Parellada, 2017 650 *All prices are in thousand rupiah and subject to government tax and service charge -

Monarcas, Bufones, Políticos Y Audiencias Comparación De La Sátira Televisiva En Reino Unido Y España, Revista Latina De Comu

Valhondo Crego, J. L. (2011): Monarcas, bufones, políticos y audiencias Comparación de la sátira televisiva en Reino Unido y España, Revista Latina de Comu... Investigación | Forma de citar/how to cite | informe de revisores/referees | agenda | metadatos | formato para imprimir | PDF dinámico | Creative Commons DOI: 10.4185/RLCS-66-2011-932-252-273 | ISSN 1138-5820 | RLCS # 66 | 2011 | | Monarcas, bufones, políticos y audiencias. Comparación de la sátira televisiva en Reino Unido y España Monarchy, jesters, politicians and audiences. Comparison of TV satire in UK and Spain Dr. José-Luis Valhondo-Crego [C.V.] Doctor por la Universidad Rey Juan Carlos de Madrid - [email protected] Resumen: Los programas de sátira se han convertido en una forma de comunicación política frecuente en la televisión. Tras la liberalización de los medios y la globalización de los formatos, países como España han adoptado formatos satíricos procedentes de otros que, como Reino Unido, contaban con una tradición que se remontaba casi al inicio de la televisión. El objetivo de este artículo es el de pergeñar una definición del género teniendo en cuenta los ejemplos de los dos países mencionados y, también, refiriéndonos a dos épocas separadas por el fenómeno de la liberalización de la televisión. Aplicaremos para ello una metodología comparativa respecto al perfil de las audiencias, de los bufones de la sátira y del papel jugado por la clase política a lo largo de la corta historia de la sátira en televisión. Los resultados señalan una evolución. En los años sesenta del siglo XX, el género apuntaba a las clases medias, sus autores pretendían popularizar la política para una sociedad muy respetuosa con el establishment y los políticos censuraron el espacio en previsión de que pudiera desequilibrar ideológicamente los procesos electorales.