2:15 Pm Dirksen Senate Office Building

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analyzing the Obama Administration's Efforts of Reconciliation with Native

Michigan Journal of Race and Law Volume 22 2017 Legacy in Paradise: Analyzing the Obama Administration’s Efforts of Reconciliation with Native Hawaiians Troy J.H. Andrade William S. Richardson School of Law, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, Law and Race Commons, and the President/Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation Troy J. Andrade, Legacy in Paradise: Analyzing the Obama Administration’s Efforts of Reconciliation with Native Hawaiians, 22 MICH. J. RACE & L. 273 (2017). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl/vol22/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of Race and Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LEGACY IN PARADISE: ANALYZING THE OBAMA ADMINISTRATION’S EFFORTS OF RECONCILIATION WITH NATIVE HAWAIIANS Troy J.H. Andrade* This Article analyzes President Barack Obama’s legacy for an indigenous people—nearly 125 years in the making—and how that legacy is now in consid- erable jeopardy with the election of Donald J. Trump. This Article is the first to specifically critique the hallmark of Obama’s reconciliatory legacy for Native Hawaiians: an administrative rule that establishes a process in which the United States would reestablish a government-to-government relationship with Native Hawaiians, the only indigenous people in America without a path toward federal recognition. -

Hawaii Attorney General Legal Opinion 95-03

Hawaii Attorney General Legal Opinion 95-03 July 17, 1995 The Honorable Benjamin J. Cayetano Governor of Hawaii Executive Chambers Hawaii State Capitol Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 Dear Governor Cayetano: Re: Authority to Alienate Public Trust Lands This responds to your request for our opinion as to whether the State has the legal authority to sell or dispose of ceded lands. For the reasons that follow, we are of the opinion that the State may sell or dispose of ceded lands. We note that any proceeds of the sale or disposition must be returned to the trust and held by the State for use for one or more of the five purposes set forth in § 5(f) of the Admission Act, Pub. L. No. 86-3, 73 Stat. 4 (1959)(the "Admission Act"). In Part I of this opinion, we determine that under the Admission Act and the Constitution the State is authorized to sell ceded lands. In Part II, we conclude that the 1978 amendments to the State Constitution do not alter the State's authority. I. The Admission Act Authorizes the Sale or Disposition of Public Trust Land. The term "ceded land" as used in this opinion is synonymous with the phrase "public land and other public property" as defined in § 5(g) of the Admission Act: [T]he term "public lands and other public property" means, and is limited to, the lands and properties that were ceded to the United States by the Republic of Hawaii under the joint resolution of annexation approved July 7, 1898 (30 Stat. -

G:\OSG\Desktop

No. 07-1372 In the Supreme Court of the United States STATE OF HAWAII, ET AL., PETITIONERS v. OFFICE OF HAWAIIAN AFFAIRS, ET AL. ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF HAWAII BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE SUPPORTING PETITIONERS GREGORY G. GARRE Solicitor General Counsel of Record RONALD J. TENPAS Assistant Attorney General DARYL JOSEFFER EDWIN S. KNEEDLER Deputy Solicitors General WILLIAM M. JAY Assistant to the Solicitor General DAVID C. SHILTON JOHN EMAD ARBAB DAVID L. BERNHARDT Attorneys Solicitor Department of Justice Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 20530-0001 Washington, D.C. 20240 (202) 514-2217 QUESTION PRESENTED Whether the resolution adopted by Congress to ac- knowledge the United States’ role in the 1893 overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii strips the State of Hawaii of its present-day authority to sell, exchange, or transfer 1.2 million acres of land held in a federally created land trust unless and until the State reaches a political settle- ment with native Hawaiians about the status of that land. (I) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Interest of the United States............................ 1 Statement............................................ 2 Summary of argument................................. 8 Argument: Congress’s apology left untouched the governing federal law, which precludes any injunction against sale of trust lands based on putative unrelinquished claims to those lands .............................. 11 I. The United States acquired absolute title at annexation and authorized Hawaii to sell or transfer lands as trustee, consistent with the trust requirements............................ 11 A. In annexing Hawaii, the United States acquired absolute title to the ceded lands..... 12 1. -

Excerpt from Ch. 2 on the Public Land Trust from Native Hawaiian

Public Land Trust Excerpt from Ch. 2, "Public Land Trust" by Melody Kapilialoha MacKenzie, in Native Hawaiian Law: A Treatise (2015), a collaborative project of the Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation, Ka Huli Ao Center for Excellence in Native Hawaiian Law at the William S. Richardson School of Law, and Kamehameha Publishing. Copyright © 2015 by the Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation & Ka Huli Ao Center for Excellence in Native Hawaiian Law. All rights reserved. I. INTRODUCTION In 1898, based on a Joint Resolution of Annexation (Joint Resolution) enacted by the U.S. Congress, the Republic of Hawai‘i transferred approximately 1.8 million acres2 of Hawaiian Government and Crown Lands to the United States.3 Kamehameha III had set aside the Government Lands in the 1848 Māhele for the benefit of the chiefs and people. The Crown Lands, reserved to the sovereign, provided a source of income and support for the crown and, in turn, were a resource for the Hawaiian people.4 Although the fee-simple ownership system instituted by the Māhele and the laws that followed drastically changed Hawaiian land tenure, the Government and Crown Lands were held for the benefit of all the Hawaiian people. They marked a continuation of the trust concept that the sovereign held the lands on behalf of the gods and for the benefit of all.5 In the Joint Resolution, the United States implicitly recognized the trust nature of the Government and Crown Lands. Nevertheless, large tracts of these lands were set aside by the federal government for military purposes during the territorial period and continue under federal control today. -

The Myth of Ceded Lands and the State's Claim

OFFICE of HAWAIIAN AFFAIRS KA WAI OLA NEWSPAPER 711 Kapi‘olani Blvd., Ste. 500 • Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96813-5249 'Apelila 2009 • Vol. 26, No. 4 www.oha.org/kwo/2009/04 Powered by Search Ka Wai Ola The myth of ceded lands and the state's Search Search Web claim to perfect title FREE SUBSCRIPTION TO KA WAI OLA KA WAI OLA WEB EDITIONS KA WAI OLA LOA WEB EDITIONS By Keanu Sai 'Apelila 2009: In the recent ceded lands hearing at the Supreme Court in Washington, D.C., on Feb. 25, Attorney General Mark Bennett repeatedly asserted that the State of Hawai'i has perfect title to more than 1 million acres of land that were transferred to the United States government upon annexation in 1898 and then transferred to the State of Hawai'i in 1959. This is an incorrect statement. This falsehood, however, is not based on arguments for or against the highly charged Hawaiian sovereignty movement; rather, it is a simple question to answer since ownership of land is not a matter of rhetoric but dependent on a sequence of deeds in a chain of title between the party granting title and the party receiving title. In fact, the term "perfect title" in real-estate terms means "a title that is free of liens and legal questions as to ownership of the property. A requirement for the sale of real estate." Download a complete What determines a perfect title is a chain of title that doesn't PDF version of this edition have a missing link. -

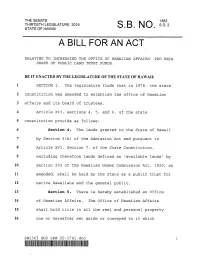

A Bill for an Act

THE SENATE 1363 THIRTIETH LEGISLATURE, 2019 ' ' ' so. 2 STATE 0F HAWAII S B N O . A BILL FOR AN ACT_ RELATING TO INCREASING THE OFFICE OF HAWAIIAN AFFAIRS' PRO RATA SHARE OF PUBLIC LAND TRUST FUNDS. BE IT ENACTED BY THE LEGISLATURE OF THE STATE OF HAWAII: SECTION l. The legislature finds that in 1978, the state constitution was amended to establish the office of Hawaiian affairs and its board of trustees. Article XII, sections 4, 5, and 6, of the state constitution provide as follows: Section 4. The lands granted to the State of Hawaii by Section 5(b) of the Admission Act and pursuant to Article XVI, Section 7, of the State Constitution, excluding therefrom lands defined as "available lands" by 10 Section.203 of the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act, 1920, as 11 amended, shall be held by the State as a public trust for 12 native Hawaiians and the general public. l3 Section 5. There is hereby established an Office 14 of Hawaiian Affairs. The Office of Hawaiian Affairs 15 shall hold title to all the real and personal property 16 now or hereafter set aside or conveyed to it which SBl363 SD2 LRB 20—174l.doc ‘WWHI!\lllilllfllfllElilfllflflllllliflllllllIIHIEH\l!lllfllflflllfllllfl\\|\\\llfll||l|flllHl\Hl\ll‘l‘flllifll‘ SB. NO. 33.32 shall be held in trust for native Hawaiians and Hawaiians. There shall be a board of trustees for the Office of Hawaiian Affairs elected by qualified voters as provided by law. There shall be not less than nine members of the board of trustees; provided that each of the following Islands have one representative: Oahu, Kauai, Maui, Molokai and Hawaii. -

Nation of Hawai`I 41-1300 Waikupanaha Street • Waimanalo, Oahu • Hawaii 96795 808.551.5056 • [email protected] •

Nation of Hawai`i 41-1300 Waikupanaha Street • Waimanalo, Oahu • Hawaii 96795 808.551.5056 • [email protected] • www.bumpykanahele.com Date: April 18, 2010 The Honorable Hillary Rodham Clinton Secretary of State U.S. Department of State 2201 C Street NW Washington, DC 20520 Submitted via the US State Department representatives attending the UPR “Listening Session” in Albuquerque New Mexico March 16th 2010 Aloha Madam Secretary, There are a lot of important things going on in Hawaii affecting the Native Hawaiian People which are being done without full their knowledge and consent. The Akaka Bill as one example has been the most high profile issue and legislation to date. A handful of very powerful politicians and leaders of several major Hawaiian organizations have, through this legislation, taken upon themselves to decide what form of government is best for the Hawaiian People. This is far from the definition of self- determination under international law as per Article 1, paragraph 2 of the UN Charter, Article 1 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political rights which the US ratified in 1992 and Article 1 of the . International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. The Akaka bill legislation should never have gotten this far without extensive education, input and finally, consent and agreement by the Hawaiian People as a whole. In 1945, the United States, under the United Nations Decolonization process as spelled out in Article 73 of the Charter, accepted as a sacred trust obligation to promote a full measure of self government for the Hawaiian people. They were to ensure the Hawaiian people their political, economic, social, and educational advancement, just treatment, and protection against abuses. -

Restoration of Independence for Hawaiʽi Michael Haas

Restoration of Independence for Hawaiʽi Michael Haas Abstract: The Kingdom of Hawaiʽi was deposed in 1893 by a coup supported by soldiers of the United States although not accepted by the president of the United States as a violation of international law. In 1898, Congress voted to annex Hawaiʽi and American control has continued to the present. Today, some desire to restore Hawaiʽi as an independent country. The paper analyzes eight reasons supporting independence and the feasibility of such a transfer of sovereignty. Word Count: 7463 Keywords: colonization, decolonization, imperialism, self-determination, sovereignty, United Nations Some now believe that the Hawaiian Islands deserve to become an independent country again. Is that pursuit justifiable or even feasible? In this paper, I attempt the first comprehensive analysis of a policy question that is destined to shock the United States and the world. Should Hawaiʽi Be Independent? 1. The Kingdom of Hawaiʽi, independent up to 1893, was a progressive country in many ways. In 1839, Kamehameha III issued a Declaration of Rights and the Edict of Toleration. The Rights protected for “all people of all lands” were identified as “life, limb, liberty, freedom from oppression; the earnings of his hands and the productions of his minds.” The chiefs were explicitly informed that they would lose their noble status if they mistreated commoners. Religious liberty has been observed ever since. In 1840, on behalf of the “Hawaiian Islands,” Kamehameha III and Queen Kekāuluohi promulgated a British-style government. The body of chiefs that formerly met at the pleasure of the king became an appointive 16-member House of Nobles, including the king as a member, along with a “representative body,” initially chosen by the king from letters of nomination; those with the most nominations were appointed by the king (Kuykendall 1938:228). -

![Traditional Land Tenure Use [Intro – Julie]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4698/traditional-land-tenure-use-intro-julie-2114698.webp)

Traditional Land Tenure Use [Intro – Julie]

[Need Settlement Pattern Photo]Traditional Land Tenure Use [Intro – Julie] Today on Maui there are issues related to land tenure that are directly connected to the Hawaiian period. To become familiar with these requires at least some knowledge of how traditional Hawaiian tenure and land use evolved, how it was structured, and ultimately, how it was compromised over time. By the early 1600s, Maui was divided into twelve districts or Moku. A Moku functioned as the basic land holding unit and was the domain of the chief, island, or subdivision thereof. They included Hamakuaola, Hamakuapoko, Hana, Honua’ula, Ka’anapali, Kahikinui, Kaupo, Kipahulu, Ko’olau, Kula, Lahaina, and Wailuku. In addition, the islands of Lana’i, Moloka’i, and Kaho’olawe were designated Moku of Maui. 1838 Each Moku was divided into smaller land units or Ahupua’a. They ranged in size from 100-10,000 acres. Their boundaries were natural and conse- quently, the ideal ahupua’a was roughly triangular in shape and ran from the mountain top (mauka) to the sea (makai). The first map of Maui that showed the Ahupua’a was drawn in 1838 by Kalama. Maui Ahupua`a There were 141 Ahupua‘a designated for the island Ahupua’a Walls Source: Patrick, Katherine Lokelani. Kamehameha Lokelani. Katherine Patrick, Source: 2005 Campus, Maui Schools, Each Ahupua‘a was divided into sections or Ili. They were of variable acreage and their boundaries were also natural. They consisted of mountains or uplands, known as Uka, plains or fields, known as Kula, and coastal lands and the sea or Kai. -

AKAKA BILL by GAIL HERIOT* Effect

“ALOHA!,” AKAKA BILL BY GAIL HERIOT* effect. The intervening months created an opportunity for awaii has long been known for its warm and more careful public consideration of the bill. Most notably, welcoming “Spirit of Aloha.” It’s hard to believe its after a public briefing, the United States Commission on Hpolitics could be any different. But at least with regard Civil Rights issued a report on May 18, 2006, which stated to issues of race and ethnicity, Hawaiian politics falls well the Commission’s conclusion very plainly: short of the Aloha standard. In a nation in which special benefits, based on race or The Commission recommends against passage ethnicity, are part of the political landscape in nearly every of the Native Hawaiian Government state, Hawaii is in a class by itself. Special schools, special Reorganization Act of 2005 . or any other business loans, special housing and many other benefits legislation that would discriminate on the basis are available to those who can prove their Hawaiian of race or national origin and further subdivide bloodline. “Haole,” as some ethnic Hawaiians refer to whites, the American people into discrete subgroups need not apply. And the same goes for African Americans, accorded varying degree of privilege.2 Hispanics, or Asian Americans—no matter how long they or their families have lived on the islands. Meanwhile, newspaper columnists were commentating As explained further below, it is against that and bloggers blogging. Even radio talk show hosts got in background that the proposed Native Hawaiian Government on the act. Slowly, well-informed voters were learning about Reorganization Act (known as the “Akaka bill”)1 is best the Akaka bill. -

In Fltbe ~Upreme Qcourt of Tbe Ilnittb ~Tates --- . --- STATE of HAWAII, ET AL., PETITIONERS

No. 07-1372 In fltbe ~upreme QCourt of tbe Ilnittb ~tates ---_._--- STATE OF HAWAII, ET AL., PETITIONERS, v. OFFICE OF HAWAIIAN AFFAIRS, ET AL. ---_._-- ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF HAWAII -...,....---_._--- AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF OF ABIGAIL KINOIKI KEKAULIKE KAWANANAKOA IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS ---_._--- GEORGE W. VAN BUREN Counsel of Record VAN BUREN CAMPBELL & SHIMIZU 745 Fort Street, Suite 1950 Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 (808) 599-3800 Attorneys for Amicus Curiae Abigail Kinoiki Kekaulike Kawananakoa University of Hawaii School of Law Library - Jon Van Dyke Archives Collection 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ...................................... ii IDENTITY AND INTEREST OF AMI CUS CURIAE ............................................ 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ..................................... 4 ARGUMENT ............................................................... 7 CONCLUSION .......................................................... 17 University of Hawaii School of Law Library - Jon Van Dyke Archives Collection 11 TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Cases Office of Hawaiian Affairs v. Housing and Community Development Corporation of Hawai'i, 177 P.3d 884 (2008) ................................ 4 Hawaii Housing Authority v. Midkiff, 467 U.S. 229, 232, 104 S.Ct. 2321, 81 L.Ed.2d 186 (1984) ............................................ 7 State by Kobayashi v. Zimring, 566 P .2d 725 (1977) ............................................... 9 In the Matter of the Estate of His Majesty Kamehameha N, 2 Haw. 715 (1864) ................. -

Stopping the Wind-An Exploration of the Hawaiian Sovereignty Movmement

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Communication Master of Arts Theses College of Communication Spring 6-2010 Stopping the Wind-An Exploration of the Hawaiian Sovereignty Movmement Krystle R. Klein DePaul University Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/cmnt Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Klein, Krystle R., "Stopping the Wind-An Exploration of the Hawaiian Sovereignty Movmement" (2010). College of Communication Master of Arts Theses. 7. https://via.library.depaul.edu/cmnt/7 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Communication at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Communication Master of Arts Theses by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ‘Imi na’auao—to seek enlightenment, wisdom and education ‘Ike Pono—to know, see, feel, to understand, to comprehend, to recognize/righteous, appropriate, moral goodness, proper, fair Kuleana—privilege, responsibility, area of responsibility (the responsibility which accompanies our blessings) This project was a discovery of truth, and on a deeper level, the journey of ‘Imi na’auao. In discovering the truth of the islands, and hearing the stories from those who live it, ‘Ike Pono was achieved. As a person blessed and cursed with privilege, it is my duty to respond with Kuleana. The series of events that led to this final project are not riddled by mere coincidence. My experience while living on the island of O’ahu compelled me to look deeper into an otherwise untold story to many. The truth and allure of the islands drew me in.