Deptford Creekside Conservation Area Appraisal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scandal, Child Punishment and Policy Making in the Early Years of the New Poor Law Workhouse System

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Lincoln Institutional Repository ‘Great inhumanity’: Scandal, child punishment and policy making in the early years of the New Poor Law workhouse system SAMANTHA A. SHAVE UNIVERSITY OF LINCOLN ABSTRACT New Poor Law scandals have usually been examined either to demonstrate the cruelty of the workhouse regime or to illustrate the failings or brutality of union staff. Recent research has used these and similar moments of crisis to explore the relationship between local and central levels of welfare administration (the Boards of Guardians in unions across England and Wales and the Poor Law Commission in Somerset House in London) and how scandals in particular were pivotal in the development of further policies. This article examines both the inter-local and local-centre tensions and policy conseQuences of the Droxford Union and Fareham Union scandal (1836-37) which exposed the severity of workhouse punishments towards three young children. The paper illustrates the complexities of union co-operation and, as a result of the escalation of public knowledge into the cruelties and investigations thereafter, how the vested interests of individuals within a system manifested themselves in particular (in)actions and viewpoints. While the Commission was a reactive and flexible welfare authority, producing new policies and procedures in the aftermath of crises, the policies developed after this particular scandal made union staff, rather than the welfare system as a whole, individually responsible for the maltreatment and neglect of the poor. 1. Introduction Within the New Poor Law Union workhouse, inmates depended on the poor law for their complete subsistence: a roof, a bed, food, work and, for the young, an education. -

Vagrants and Vagrancy in England, 1485-1553

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1986 Basilisks of the Commonwealth: Vagrants and Vagrancy in England, 1485-1553 Christopher Thomas Daly College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Daly, Christopher Thomas, "Basilisks of the Commonwealth: Vagrants and Vagrancy in England, 1485-1553" (1986). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625366. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-y42p-8r81 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BASILISKS OF THE COMMONWEALTH: Vagrants and Vagrancy in England, 1485-1553 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts fcy Christopher T. Daly 1986 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts . s F J i z L s _____________ Author Approved, August 1986 James L. Axtell Dale E. Hoak JamesEL McCord, IjrT DEDICATION To my brother, grandmother, mother and father, with love and respect. iii TABLE OE CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................. v ABSTRACT.......................................... vi INTRODUCTION ...................................... 2 CHAPTER I. THE PROBLEM OE VAGRANCY AND GOVERNMENTAL RESPONSES TO IT, 1485-1553 7 CHAPTER II. -

The Poor Law of 1601

Tit) POOR LA.v OF 1601 with 3oms coi3ii3rat,ion of MODSRN Of t3l9 POOR -i. -S. -* CH a i^ 3 B oone. '°l<g BU 2502377 2 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Chapter 1. Introductory. * E. Poor Relief before the Tudor period w 3. The need for re-organisation. * 4. The Great Poor La* of 1601. w 5. Historical Sketch. 1601-1909. " 6. 1909 and after. Note. The small figares occurring in the text refer to notes appended to each chapter. Chapter 1. .Introductory.. In an age of stress and upheaval, institutions and 9 systems which we have come to take for granted are subjected to a searching test, which, though more violent, can scarcely fail to be more valuable than the criticism of more normal times. A reconstruction of our educational system seems inevitable after the present struggle; in fact new schemes have already been set forth by accredited organisations such as the national Union of Teachers and the Workers' Educational Association. V/ith the other subjects in the curriculum of the schools, History will have to stand on its defence. -

Caring for the Poor, Sick and Needy. a Brief History of Poor Relief in Scotland

Caring for the poor, sick and needy. A brief history of poor relief in Scotland Aberdeen City Archives Contents 1. A brief history of poor relief up to 1845 2. A brief history of poor relief after 1845 3. Records of poor relief in Scotland: a. Parochial Board/Parish Council Minute Books b. Records of Applications c. General Registers of the Poor d. Children’s Separate Registers e. Register of Guardians f. Assessment Rolls g. Public Assistance Committee Minutes 4. Records for Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire 5. Further Reading 2 1. A brief history of poor relief up until 1845 The first acts of parliament to deal with the relief of the poor were passed in 1424. Most of these and subsequent acts passed in the 15th and 16th centuries. dealt with beggars and little information on individuals survives from this time. After the Reformation, the responsibility for the poor fell to the parish jointly through the heritors, landowners and officials within burghs who were expected to make provision for the poor and were also responsible for the parish school til 1872 and the church and manse til 1925, and the Kirk Sessions (the decision making body of the (or local court) of the parish church, made up of a group of elders, and convened (chaired) by a minister. The heritors often made voluntary contributions to the poor fund in preference of being assessed, and the kirk sessions raised money for the poor from fines, payments for carrying out marriages, baptisms, and funerals, donations, hearse hiring, interest on money lent, rent incomes and church collections. -

ARCHITECTURE, POWER, and POVERTY Emergence of the Union

ARCHITECTURE, POWER, AND POVERTY Emergence of the Union Workhouse Apparatus in the Early Nineteenth-Century England A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Gökhan Kodalak January 2015 2015, Gökhan Kodalak ABSTRACT This essay is about the interaction of architecture, power, and poverty. It is about the formative process of the union workhouse apparatus in the early nineteenth-century England, which is defined as a tripartite combination of institutional, architectural, and everyday mechanisms consisting of: legislators, official Poor Law discourse, and administrative networks; architects, workhouse buildings, and their reception in professional journals and popular media; and paupers, their everyday interactions, and ways of self-expression such as workhouse ward graffiti. A cross-scalar research is utilized throughout the essay to explore how the union workhouse apparatus came to be, how it disseminated in such a dramatic speed throughout the entire nation, how it shaped the treatment of pauperism as an experiment for the modern body-politic through the peculiar machinery of architecture, and how it functioned in local instances following the case study of Andover union workhouse. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Gökhan Kodalak is a PhD candidate in the program of History of Architecture and Urbanism at Cornell University. He received his bachelor’s degree in architectural design in 2007, and his master’s degree in architectural theory and history in 2011, both from Yıldız Technical University, Istanbul. He is a co-founding partner of ABOUTBLANK, an inter-disciplinary architecture office located in Istanbul, and has designed a number of award-winning architectural and urban design projects in national and international platforms. -

Almshouse, Workhouse, Outdoor Relief: Responses to the Poor in Southeastern Massachusetts, 1740-1800” Historical Journal of Massachusetts Volume 31, No

Jennifer Turner, “Almshouse, Workhouse, Outdoor Relief: Responses to the Poor in Southeastern Massachusetts, 1740-1800” Historical Journal of Massachusetts Volume 31, No. 2 (Summer 2003). Published by: Institute for Massachusetts Studies and Westfield State University You may use content in this archive for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the Historical Journal of Massachusetts regarding any further use of this work: [email protected] Funding for digitization of issues was provided through a generous grant from MassHumanities. Some digitized versions of the articles have been reformatted from their original, published appearance. When citing, please give the original print source (volume/ number/ date) but add "retrieved from HJM's online archive at http://www.westfield.ma.edu/mhj. Editor, Historical Journal of Massachusetts c/o Westfield State University 577 Western Ave. Westfield MA 01086 Almshouse, Workhouse, Outdoor Relief: Responses to the Poor in Southeastern Massachusetts, 1740-1800 By Jennifer Turner In Duxbury, Massachusetts, local folklore emphasizes that before the current Surplus Street was named, it was called Poverty Lane because it led to the “poor” farm, and before it was Poverty Lane, local residents knew it as Folly Street, over which one’s folly led to the Almshouse.1 Although such local folklore suggests a rather stringent attitude towards giving alms to the poor in colonial society, the issue of poor relief absorbed much of the attention of town officials before and after the American Revolution. Throughout the colonial period and early republic, many Massachusetts towns faced growing numbers of needy men, women and children in need of relief. -

May 2016 • Issue 35

May 2016 • Issue 35 A newsletter by residents for residents Have your say Use your vote to award £100,000! Festival Odyssey 70s legends to headline Phoenix Festival community news Focus on… Rent and service charges Welcome… Looking for our contact details? Turn to the back page! Welcome to Community News This May edition of Community News is jam-packed with updates and competitions for you. Summer is almost here and we’re getting ready for the Phoenix Festival on Saturday 14 May at Forster Park. Lots of popular activities will be returning as well as some new and exciting events. These include a Community Parade which will pass through Downham before kicking off the festival! Why not bring your dog to take part in our new dog show too? At the festival you will also be able to meet the larger projects which have been shortlisted for Community Chest funding. Smaller projects have already been selected by our panel – turn to pages 10 and 11 to find out who was successful. The projects will benefit our whole community and everyone can get involved. Downham is celebrating its 90th birthday this year and there’s more information on Page 10 and 11 about how you can get involved in the celebrations. We also hear from Eileen Hale, a resident who has lived in the same home for 88 years. Her WIN! ‘Spot yourself!’ memories of the area really showed us how much has changed If this is you, pictured at our over the years. Read her story on Page 9. -

2019 CV.Qxp New CV 6/03

drGaryostle curriculum vitae : profile Drostle Public Arts Ltd Studio B – The Lakeside Centre Bazalgette Way London, SE2 9AN. United Kingdom WEB: www.drostle.com EMAIL: [email protected] artists statement MOB: +44 771 952 952 0 This simple hand print logo can be seen as lying at the core of my artistic vision, it’s origin is perhaps human kinds most ancient creative expression and can be seen in cave paintings over 50,000 years old, the signature of the first mural artists. Of course it’s not a print, rather the impression left after the hand has been removed and as such symbolises the marks left on the environment by people now departed. To me this is a profoundly democratic view of art for all, on the street, enhancing and changing our environment, interacting with people, landscape and architecture reflecting a sense of place through the expression of our history and humanity, it is this that inspires me. My practice concentrates on working in large scale painted murals, mosaics for floors and walls and mosaic sculptures. In developing this work I draw on the specific site, its history and stories, its architecture and landscape and its community and users to create works which are specific to each site, enduring and beautiful. My experience includes working with other artists, council officers, architects, landscapers, interior designers, planners, engineers and contractors and I have worked extensively with a wide variety of community groups at every level of the creative process. Drostle Public Arts Ltd – REG No:7775382 drGaryostle curriculum vitae page 2 background & training I was born in London in 1961 and began my practice as a professional public artist soon after leaving art college in Camberwell School of Art 1984. -

'Twenty-Five' Churches of the Southwark Diocese

THE ‘TWENTY-FIVE’ CHURCHES OF THE SOUTHWARK DIOCESE THE ‘TWENTY-FIVE’ CHURCHES OF THE SOUTHWARK DIOCESE An inter-war campaign of church-building Kenneth Richardson with original illustrations by John Bray The Ecclesiological Society • 2002 ©KennethRichardson,2002.Allrightsreserved. First published 2002 The Ecclesiological Society c/o The Society of Antiquaries of London Burlington House Piccadilly London W1V 0HS www.ecclsoc.org PrintedinGreatBritainbytheAldenPress,OsneyMead,Oxford,UK ISBN 0946823154 CONTENTS Author’s Preface, vii Acknowledgements, ix Map of Southwark Diocese, x INTRODUCTION AND SURVEY, 1 GAZETTEER BELLINGHAM, St Dunstan, 15 CARSHALTON BEECHES, The Good Shepherd, 21 CASTELNAU (Barnes), Estate Church Hall, 26 CHEAM, St Alban the Martyr, 28 St Oswald, 33 COULSDON, St Francis of Assisi, 34 DOWNHAM, St Barnabas, Hall and Church, 36 St Luke, 41 EAST SHEEN, All Saints, 43 EAST WICKHAM, St Michael, 49 ELTHAM, St Barnabas, 53 St Saviour, Mission Hall, 58 and Church, 60 ELTHAM PARK, St Luke, 66 FURZEDOWN (Streatham), St Paul, 72 HACKBRIDGE & NORTH BEDDINGTON, All Saints, 74 MALDEN, St James, 79 MERTON, St James the Apostle, 84 MITCHAM, St Olave, Hall and Church, 86 MORDEN, St George 97 MOTSPUR PARK, Holy Cross, 99 NEW ELTHAM, All Saints, 100 Contents NORTH SHEEN (Kew), St Philip the Apostle & All Saints, 104 OLD MALDEN, proposed new Church, 109 PURLEY, St Swithun, 110 PUTNEY, St Margaret, 112 RIDDLESDOWN, St James, 120 ST HELIER, Church Hall, 125 Bishop Andrewes’s Church, 128 St Peter, 133 SANDERSTEAD, St Mary the Virgin, 140 SOUTH -

Page 4Celebrating 90 Years of the Downham Estate / Marking 25

4 THE BRIDGE... June 2016 Celebrating 90 years Marking of the Downham Estate 25 years The 90th anniversary of the at Christ Downham Housing Estate was celebrated on 14 May with Church the inaugral ‘Downham & Whitefoot’ Community Parade. Croydon St John the Baptist Church, part of the Catford and Christ Church, Sumner Downham Team Ministry, were Road, West Croydon will among the organisations which mark the 25th Anniversary took part in a celebration of of the current church the past, present and future On 2 April a group of 24 adults and 4 children from St Alban’s, building with a Holy with costumes and fl oats Cheam had a guided tour of the Houses of Parliament. Communion service representing all aspects of this celebrated by Bishop diverse community. Jonathan on Sunday 5 June at 10am. Other organisations taking part included The Metropolitan The church was Police, St John the Baptist completed in April 1991 on School, Whitefoot and The parade kicked off at Choir and Downham Tamil the site of a Gothic style Downham Community Food 10am at St John’s Church with Association. Local MP Victorian church which Project, Phoenix Community performances by Bellingham Heidi Alexander and Sir had been closed in 1978 Housing and Downham Community Gospel Choir, Steve Bullock, the Mayor of due to structural problems. Celebrates. St John’s Primary School Lewisham (photo left) also took Services were held in the part. church hall thereafter. The parade moved off at Plans were prepared for 11am and made its way to a rebuild but in December Forster Memorial Park where 1985, the church was badly more than 6,000 residents damaged by fi re. -

Bellingham Local History the Name Means “The Water-Meadow Belonging to Beora’S People”

London Borough of Lewisham Local History and Archives Centre Info Byte Sheet No. 33 Bellingham Local History The name means “the water-meadow belonging to Beora’s people”. It was the name of the medieval manor in this area, and survived in Bellingham Farm. It was revived in 1892 as the name of a new railway station, then in open country, on the Nunhead and Shortlands Railway. After the First World War the London County Council began to build large estates on the edge of the built-up area of London to ease overcrowding and assist slum clearance. Downham Estate, close to Bellingham, is a typical example. Because there was plenty of land available, most of the dwellings could be two-storey houses with gardens (rather than flats) interspersed with open spaces and trees. Provision was made for schools, shops, churches, parks and other amenities. The land for the Bellingham Estate (Bellingham Farm and part of White House Farm) was bought in 1920, and building of the main estate was completed in 1923. Historical names were chosen for the roads. Some were connected with King Alfred, who was thought to have been lord of the manor of Lewisham. Others were the names of old houses, fields, and mills in the area. The inhabitants came from crowded inner London areas, mainly from Deptford and Bermondsey. The extension south of Southend Lane was built between 1936 and 1939. Here more flats were built, for economy, and to meet the pressing need for housing. 2008 General Local History websites: Google Image search http://images.google.co.uk Google Book search http://www.google.co.uk/books?hl=en Genuki http://www.genuki.org.uk/big/ Dictionary of London at History online http://www.british- history.ac.uk/source.asp?pubid=3 Old Maps http://www.old-maps.co.uk/ The National Archives [Good for how to guides and http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ information on record types]. -

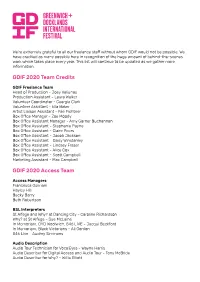

Festival Credits for GDIF 2020

We’re extremely grateful to all our freelance staff without whom GDIF would not be possible. We have credited as many possible here in recognition of the huge amount of behind-the-scenes work which takes place every year. This list will continue to be updated as we gather more information. GDIF 2020 Team Credits GDIF Freelance Team Head of Production - Joey Valiunas Production Assistant - Laura Walker Volunteer Coordinator - Georgia Clark Volunteer Assistant - Ella Baker Artist Liaison Assistant - Fae Fichtner Box Office Manager - Zoe Moody Box Office Assistant Manager - Amy Garner Buchannan Box Office Assistant - Stephanie Payne Box Office Assistant - Claire Peers Box Office Assistant - Jacob Jackson Box Office Assistant - Daisy Winstanley Box Office Assistant - Lindsey Fraser Box Office Assistant - Alice Cox Box Office Assistant - Scott Campbell Marketing Assistant - Max Campbell GDIF 2020 Access Team Access Managers Francesca Osimani Hayley Hill Becky Barry Beth Robertson BSL Interpreters St Alfege and Why? at Dancing City - Caroline Richardson Why? at St Alfege - Sue McLaine In Memoriam, OYD Woolwich, 846 LIVE - Jacqui Beckford In Memoriam, Black Victorians - Ali Gordon 846 Live - Audrey Simmons Audio Description Audio Tour Technician for VocalEyes - Wayne Harris Audio Describer for Digital Access and Audio Tour - Tony McBride Audio Describer for Why? - Willie Elliott GDIF 2020 Production Team GDIF Production Managers In Memoriam: Laura Walker Weavers of Woolwich, Gaia, OYD: Woolwich Arsenal, Weaving Together installations: Ben Bodsworth