The Cemetery at Fort Umrevinsky, in the Upper Ob Basin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Science and Nation After Socialism in the Novosibirsk Scientific Center, Russia

Local Science, Global Knowledge: Science and Nation after Socialism in the Novosibirsk Scientific Center, Russia Amy Lynn Ninetto Mohnton, Pennsylvania B.A., Franklin and Marshall College, 1993 M.A., University of Virginia, 1997 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dcpartmcn1 of Anthropology University of Virginia May 2002 11 © Copyright by Amy Lynn Ninetta All Rights Reserved May 2002 lll Abstract This dissertation explores the changing relationships between science, the state, and global capital in the Novosibirsk Scientific Center (Akademgorodok). Since the collapse of the state-sponsored Soviet "big science" establishment, Russian scientists have been engaging transnational flows of capital, knowledge, and people. While some have permanently emigrated from Russia, others travel abroad on temporary contracts; still others work for foreign firms in their home laboratories. As they participate in these transnational movements, Akademgorodok scientists confront a number of apparent contradictions. On one hand, their transnational movement is, in many respects, seen as a return to the "natural" state of science-a reintegration of former Soviet scientists into a "world science" characterized by open exchange of information and transcendence of local cultural models of reality. On the other hand, scientists' border-crossing has made them-and the state that claims them as its national resources-increasingly conscious of the borders that divide world science into national and local scientific communities with differential access to resources, prestige, and knowledge. While scientists assert a specifically Russian way of doing science, grounded in the historical relationships between Russian science and the state, they are reaching sometimes uneasy accommodations with the globalization of scientific knowledge production. -

Chapaev and His Comrades War and the Russian Literary Hero Across the Twentieth Century Cultural Revolutions: Russia in the Twentieth Century

Chapaev and His Comrades War and the Russian Literary Hero across the Twentieth Century Cultural Revolutions: Russia in the Twentieth Century Editorial Board: Anthony Anemone (Th e New School) Robert Bird (Th e University of Chicago) Eliot Borenstein (New York University) Angela Brintlinger (Th e Ohio State University) Karen Evans-Romaine (Ohio University) Jochen Hellbeck (Rutgers University) Lilya Kaganovsky (University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign) Christina Kiaer (Northwestern University) Alaina Lemon (University of Michigan) Simon Morrison (Princeton University) Eric Naiman (University of California, Berkeley) Joan Neuberger (University of Texas, Austin) Ludmila Parts (McGill University) Ethan Pollock (Brown University) Cathy Popkin (Columbia University) Stephanie Sandler (Harvard University) Boris Wolfson (Amherst College), Series Editor Chapaev and His Comrades War and the Russian Literary Hero across the Twentieth Century Angela Brintlinger Boston 2012 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: a bibliographic record for this title is available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2012 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN - 978-1-61811-202-6, Hardback ISBN - 978-1-61811-203-3, Electronic Cover design by Ivan Grave On the cover: “Zatishie na perednem krae,” 1942, photograph by Max Alpert. Published by Academic Studies Press in 2012 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. -

Modernism and the Spiritual in Russian Art New Perspectives

Modernism and the Spiritual in Russian Art New Perspectives EDITED BY LOUISE HARDIMAN AND NICOLA KOZICHAROW To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/609 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Modernism and the Spiritual in Russian Art New Perspectives Edited by Louise Hardiman and Nicola Kozicharow https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2017 Louise Hardiman and Nicola Kozicharow. Copyright of each chapter is maintained by the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Louise Hardiman and Nicola Kozicharow, Modernism and the Spiritual in Russian Art: New Perspectives. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2017, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0115 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/609#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/609#resources Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. -

Fishes of Mongolia a Check-List of the fi Shes Known to Occur in Mongolia with Comments on Systematics and Nomenclature

37797 Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized Environment and Social Development East Asia and Pacific Region THE WORLD BANK 1818 H Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433, USA Telephone: 202 473 1000 Facsimile: 202 522 1666 E-mail: worldbank.org/eapenvironment worldbank.org/eapsocial Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized Fishes of Mongolia A check-list of the fi shes known to occur in Mongolia with comments on systematics and nomenclature Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized MAURICE KOTTELAT Fishes of Mongolia A check-list of the fi shes known to occur in Mongolia with comments on systematics and nomenclature Maurice Kottelat September 2006 ©2006 Th e International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/THE WORLD BANK 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 USA September 2006 All rights reserved. Th is report has been funded by Th e World Bank’s Netherlands-Mongolia Trust Fund for Environmental Reform (NEMO). Some photographs were obtained during diff erent activities and the author retains all rights over all photographs included in this report. Environment and Social Development Unit East Asia and Pacifi c Region World Bank Washington D.C. Contact details for author: Maurice Kottelat Route de la Baroche 12, Case Postale 57, CH-2952 Cornol, Switzerland. Email: [email protected] Th is volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/Th e World Bank. Th e fi ndings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily refl ect the views of the Executive Directors of Th e World Bank or the governments they represent. -

Peter Slovtsov, Ivan Kalashnikov, and the Saga of Russian Siberia

ENLIGHTENING THE LAND OF MIDNIGHT: PETER SLOVTSOV, IVAN KALASHNIKOV, AND THE SAGA OF RUSSIAN SIBERIA Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Mark A. Soderstrom Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Nicholas B. Breyfogle, Advisor Alice L. Conklin David L. Hoffmann Copyright by Mark A. Soderstrom 2011 ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the lives, works, and careers of Peter Andreevich Slovtsov (1767-1843) and Ivan Timofeevich Kalashnikov (1797-1863). Known today largely for their roles as Siberian “firsts”—Slovtsov as Siberia‟s first native-born historian, Kalashnikov as Siberia‟s first native-born novelist—their names often appear in discussions of the origins of Siberian regionalism, a movement of the later nineteenth century that decried Siberia‟s “colonial” treatment by the tsarist state and called for greater autonomy for the region. Drawing on a wide range of archival materials— including two decades of correspondence between the two men—this study shows that Slovtsov and Kalashnikov, far from being disgruntled critics of the tsarist state, were its proud agents. They identified with their service careers, I suggest, because they believed that autocratic rule was the best system for Russia and because serving the tsarist state provided what they saw as their greatest opportunity to participate in a progressive, world-historical saga of enlightenment. Their understanding of this saga and its Russian reverberations gave form and content to their senses of self. An exploration of Slovtsov and Kalashnikov‟s complex lives through the long paper trail that makes them accessible today offers revealing perspectives on the social, cultural, and intellectual history of Russia—in particular on topics of service, selfhood, bureaucratic culture, education, and the intersection of public and private life—as well as ii on the history of Siberia and its place in the empire. -

The Creation of a 'People's Hero': Vasilii Ivanovich Chapaev and The

The Creation of a ‘People’s Hero’: Vasilii Ivanovich Chapaev and the Fate of Soviet Popular History By Jason Read Morton A dissertion submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Yuri Slezkine, Chair Professor Victoria Frede Professor Anne Nesbet Spring 2017 i Abstract The Creation of a ‘People’s Hero: Vasilii Ivanovich Chapaev and the Fate of Soviet Popular History By Jason Read Morton Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Yuri Slezkine, Chair This dissertation is an analysis of the relationship between grand narratives and individual identity in the Soviet context analyzed through the popular mythology of Vasilii Ivanovich Chapaev. It uses the concept of heroism effectively to bridge the divide between the collective and the discrete historical actor. The category of the hero, long central to historical narratives, has garnered scant attention in recent years. Contemporary history, which tends to emphasize the ‘bottom-up,’ has rightly pushed back against the representation of history as the province of powerful individuals. Yet heroism, too, can be explored from a bottom-up perspective by analyzing individual and popular engagement with, and influence on, heroic ideals. The popular mythology of Vasilii Ivanovich Chapaev is without an equivalent in Soviet History and offers critical insight into the dialectics of popular legitimacy in the world’s first socialist state. In Russia today, the widespread proliferation of images and stories about the peasant partisan leader, who went on to command a Bolshevik division during the Russian Civil War before dying in battle in 1919, is known as the “Chapaev Phenomenon.” Chapaev’s status in Russian memory is second only to that of Lenin, both in prevalence and longevity. -

Russian Library of Science Providing Best Articles and Papers from Research Institutes and Scientific Societies in Russia

ABCD springer.com Russian Library of Science Providing best articles and papers from research institutes and scientific societies in Russia Springer brings you By maintaining relationships with the academic institutions of other countries and regions, the best advances in Springer advances its long standing reputation as a global scientific, technical and medical Russian science and publisher. technology With SpringerLink, access to Russia’s most important research work becomes easy. With the growing significance of the research output from Russia, it will become one of the most important 7 More than 200 highly sources of research information for the scientific communities worldwide. regarded academic journals from Russia translated to Springer is offering subscribers a unique, highly comprehensive collection of English-language English-language journals from the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS) and other leading Russian language institutions under the name of Russian Library of Science. 7 Covering all disciplines 7 Including prestigious Russian Library of Science publications as the Journal of Experimental and By the introduction of the Russian Library of Science to researchers and libraries globally, Theoretical Physics, Springer unlocks the door to Russian scientific work. Springer’s Russian Library of Science JETP Letters, Physics of the broadens the doorway for the global scientific community to gain rapid access to important Solid State and Doklady Russian research. Mathematics MAIK Nauka/Interperiodica and Allerton Press, both divisions of Pleiades Publishing Inc., and 7 All journal are Springer cooperate for more than 120 journals under the Russian Academy of Sciences and peer-reviewed, most additional titles of Russian origin. with an impact factor In addition, journals in the Russian Library of Science originate from such prestigious 7 Easy accessible and locations as: searchable on SpringerLink 7 Steklov Mathematical Institute 7 Lebedev Physics Institute 7 Moscow State University. -

Ak Jang in the Context of Altai Religious Tradition

AK JANG IN THE CONTEXT OF ALTAI RELIGIOUS TRADITION A Thesis submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research In partial fulfillment of the Requirements For the Master’s Degree In the Department of Religious Studies and Anthropology University of Saskatchewan By Andrei Vinogradov © Copyright Andrei Vinogradov, November 2003. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or the professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which this thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Request for permission to copy or to make other use of the material in this thesis in whole or in part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Religious Studies and Anthropology, University of Saskatchewan i ABSTRACT In 1904, a Native religious movement, Ak Jang, formed in Gorny Altai in Southwestern Siberia. -

Sobolev and the Calculus of the Twentieth Century

УДК 51(470):517.982.4 Дата поступления 14 февраля 2008 г. Кутателадзе С. С. Sobolev and the Calculus of the Twentieth Century. Новосибирск, 2008. 26 с. (Препринт / РАН. Сиб. отд-ние. Ин-т математики; № 202). Kutateladze S. S. Sobolev and the Calculus of the Twentieth Century Два доклада о С. Л. Соболеве (1908–1989) и его вкладе в формирование совре- менных аналитических воззрений. Two talks about Serge˘ıSobolev (1908–1989) and his contribution to the modern views of mathematics. 1. Sobolev of the Euler School. 2. Sobolev and Schwartz: Two Fates and Two Fames. Адрес автора: Институт математики им. С. Л. Соболева СО РАН пр. Академика Коптюга, 4 630090 Новосибирск, Россия E-mail: [email protected] c Кутателадзе С. С., 2008 c Институт математики им. С. Л. Соболева СО РАН, 2008 Институт математики им. С. Л. Соболева СО РАН Препринт №202, февраль 2008 SOBOLEV OF THE EULER SCHOOL Serge˘ıLvovich Sobolev belongs to the Russian mathematical school and ranks among the scientists whose creativity has produced the major treasures of the world culture. Mathematics studies the forms of reasoning. Generally speaking, differentiation dis- covers trends, and integration forecasts the future from trends. Mankind of the present day cannot be imagined without integration and differentiation. The differential and integral calculus was invented by Newton and Leibniz. The fluxions of Newton and the monads of Leibniz made these giants the forerunners of the classical analysis. Euler used the concepts by Newton and Leibniz to upbring and cultivate the new mathematics of variable quantities, while making quite a few phenomenal discoveries and creating his own inexhaustible collection of miraculous formulas and theorems. -

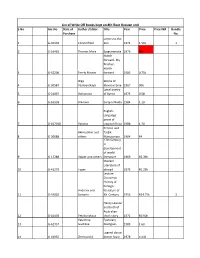

Excel- 1, Russian Write Off Books in Russian Unit Serial No. 1-3050 (1

List of Write Off books kept on 8th floor Russian unit S.No. Acc.No. Date of Author /Editor Title Year Price Price INR Bundle Purchase No. Letters to the 1G‐40103 Chesterfield Son 1971 1 51k 1 2G‐16463 Thomas More Epigrammata 1973 NA March forward, My Brother, march 3G‐62200 Farely Mowat forward 1983 0.75k Olga Works of 4G‐20587 Vasilyevskaya Steven craine 1967 90k Lyical poetry 5G‐24097 Daikonova of Byron 1975 0.58 6G‐63938 Ankrava Sarojini Naidu 1984 1.10 English‐ Language prose of 7G‐107018 Valvilov trapical Africa 1988 1.70 Persian and Akimushkin and Tadjik 8G‐20688 others Manuscripts 1964 R4 17th Century in development of world 9G‐17288 Vipper and others literature 1969 R2.39k Modern Literature of 10 G‐41279 Toper abroad 1975 R1.25k Lecture Course on Histroy of Foreign Andreev and literature of 11 G‐54820 Samarin XX Century 1956 R24.75k 2 Henry Lawson and birth of Australian 12 G‐10403 Petrikovskaya short‐story 1972 R0.90k Valentina Epstolary 13 G‐62957 Ivasheva Dialogues 1983 1.60 Legend about 14 G‐44935 Zhirmunskii doctor faust 1978 4.44k National Revolutionary war in Spain and world 15 G‐16523 L.M.Yureeva Literature 1973 NA Linguistic analysis of Ministry of artistic 16 G‐62700 Information (Literary) text 1983 1.32 Neo‐ Avantgard trends in Foreign Academy of litrature of 17 G‐21546 Sciene of USSR 1950‐60s. 1972 1.10K Neo‐ Avantgard trends in Foreign Academy of litrature of 18 42736 Sciene of USSR 1950‐60s. 1972 NA Memoires (Memories) of the current 19 G‐10720 Maya Turovskaya moments 1987 NA Modern prose and poetry of 20 136970 abroad 1983 8.00 Yannis Ritsos‐ Essay on the life and 21 G‐106987 Sofiya Ilyanskaya writings 1986 0.30K 3 Resistance poetry in Post‐ 22 G‐21168 S.B. -

Novosibirsk Akademgorodok

"Civilization" and its Insecurities: Traveling Scientists, Global Science, and National Progress in the Novosibirsk Akademgorodok Amy Ninetto, University of Virginia No civilized society can exist without science. -Vasilii Ivanovich, physicist, May 1999 In the Siberian science city of Akademgorodok, located hundreds of miles within Russia's territory, scientists move across international borders every day. Many participate in international research groups; some travel abroad to jobs and conferences several times a year. Others stay at home and "telecommute" by phone and e-mail with their colleagues and employers abroad. Nearly all depend in some way on foreign producers of equipment and reagents. Yet all this movement has not made borders-what lies within them, or what lies without-any less meaningful for Akademgorodok's scientists or the state for which many of them continue to work. As Akademgorodok has become more international, anxieties about scientists' position in the Russian nation-state have also developed. In this essay, I want to move across borders-from the story of an immigrant scientist in the United States to traveling scientists in Siberia-to open up a perspective on how former Soviet scientists are understood, perhaps paradoxically, as simultaneously essential to and threatening to the Russian nation-state. While it is easy to understand why traveling weapons scientists can be seen as threats to national security, the construction of civilian scientists as potential dangers to the nation requires an examination of the role scientists have played in constructing modernity in the Soviet Union and in post- Soviet Russia. In thinking about how scientists who move are simultaneously the focus of criticism and hope in Russia, I emphasize how a spatial narrative about the globalization of science shifts meanings as it intersects with Soviet and post-Soviet temporal narratives about national progress and decay. -

FCAA Related News, Events and Books (FCAA-Volume 17-4-2014)

EDITORIAL FCAA RELATED NEWS, EVENTS AND BOOKS (FCAA–VOLUME 17–4–2014) Virginia Kiryakova Dear readers, in the Editorial Notes we announce news for our journal, anniversaries, information on international meetings, events, new books, etc. related to the FCAA (“Fractional Calculus and Applied Analysis”) areas. This is a Special Issue partly dedicated to the 80th Anniversary of Professor Ivan Dimovski with invited papers and some selected papers from TMSF ’14 ——– 1. Great success for the FCAA Journal In the end of July 2014, Web of Knowledge of Thomson Reuters and Scopus of Elsevier announced the scientific impact metrics for 2013. FCAA have been indexed there since 2011 and it is the first time it receives these metrics officially. According to Thomson Reuters’ 2013 Journal Citation Reports (JCR) Science Edition, Release July 2014, http://admin-apps.webofknowledge.com/JCR/JCR, the Journal Title “FRACT CALC APPL ANAL” has Impact Factor JIF (2013) = 2.974. This launches our journal at rank 4/95 in category Mathematics, In- terdisciplinary Applications and rank 5/250 in category Mathematics, Applied – immediately after “SIAM Rev”, “ACM T Math Software” “Com- mun Pur Appl Math”. Although FCAA is not ranked in “Mathematics” (pure, where it would be most suitable classification), the data from JCR show that it can be there also at 4th place (of 300), after “Commun Pur Appl Math”, “J AM Math Soc”, “Acta Math (Djusholm)”, and before the next journals in the list as “Ann Math”, “Fixed Point Theory”, “Found Comput Math”, “Invent Math”, “Mem AM Math Soc”, “Duke Math J”. According to Journal Metrics Values, Scopus Release 2014, http://www.journalmetrics.com, the title “Fractional Calculus and Applied Analysis” obtained the following scientific metrics, including SJR (SCImago Journal Rang): 2012: SNIP=0.934, IPP=0.909, SJR=1.069 2013: SNIP=2.079, IPP=2.333, SJR=2.106 that confirm the excellent performance of FCAA also at Scopus database.