Certificates of Settlement & Preemption Warrants Database

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hclassification

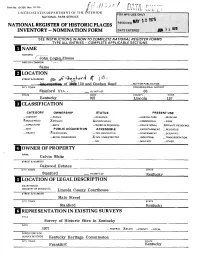

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC ^-CLogar^/House I LOCATION STREET & NUMBER U. VJUOlltUl -LXUctU CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Stanford (}{<-• _ VICINITY OF 05 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Kentucky 021 Lincoln 137 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM XBUILDINGIS) X.PRIVATE X.UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS — EDUCATIONAL -XPRIVATE RESIDENCE _SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT 2ilN PROCESS — YES: RESTRICTED _ GOVERNMENT _ SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY _ OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Calvin„ , . White„„ STREET & NUMBER Oakwood Estates CITY, TOWN STATE Stanford VICINITY OF Kentucky LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Lincoln QOUnty STREETS NUMBER Main Street CITY, TOWN STATE Stanford Kentucky REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Survey of Historic Sites in Kentucky DATE 1971 —FEDERAL XSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Kentucky Heritage Commission CITY, TOWN STATE Frankfort Kentucky DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE .EXCELLENT X.DETERIORATED UNALTERED JXORIGINALSiTE .GOOD _RUINS X.ALTERED _MOVED DATE. .FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The John Logan House is located on Logan1 s Creek at the mouth of St. Asaph's Branch. The house is situated a mile east of the center of Stanford on the old east-west road between Stanford and Rowland on U.S. Highway 150, known as the Old Wilderness Road. -

137 Covers 118 Covers.Qxd

The Emergence and Evolution of Memorial Day By Richard Gardiner, Ph.D., P. Michael Jones, and Daniel Bellware ABOUT THE AUTHORS P. Michael Jones has been the director of the General John A. Logan Museum in Murphysboro, Illinois, since 1989. His publications include The Life and Times of Major General John A. Logan (1996) and Forgotten Soldiers: Murphysboro’s African-American Civil War Veterans (1994). He is the recipient of the Illinois State Historical Society Lifetime Achievement Award and the Outstanding History Teacher award from Southern Illinois University. Daniel Bellware is an independent historical researcher in Columbus, Georgia. He is author of several articles on the American Civil War.Richard Gardiner, Ph.D. has been Associate Professor of History Education at Columbus State University since 2009. His publications include History: A Cultural Approach (2013) and several articles on history. This year commemorates the sesquicentennial anniversary of Decoration Day/Memorial Day (30 May). Today Memorial Day commemorates the men and women who sacrificed their lives in the military during war. It originally commemorated the conclusion of a war; designed to promote continued peace and reconciliation. It is our contention, however, that the narratives pertaining to the history and development of this holiday has been misinterpreted, misunderstood, and to many lost. The aim of this article is to provide a narrative in the interest of greater awareness and appreciation of the significance of the holiday. The story of the genesis of Memorial Day, an official holiday from May 1868, is not clear cut among historians, as it is traditionally taught.1 Though there are a multitude of apocryphal claims regarding who started Memorial Day and where they started it, the vast majority of accounts were manufactured many decades after the fact and are easily dismissed as myths. -

The Political Life of John A. Logan

Joyner 11 Dirty Work: The Political Life of John A. Logan Benjamin Joyner ___________________________________________________________ John Alexander Logan, the bright-eyed and raven-haired veteran of the Mexican-American and Civil War, began his career as an ardent supporter of states’ rights and a strong Democrat.1 During his years in the state legislature, Logan was a very strong supporter of enforcing the fugitive slave laws and even sponsored the Illinois Black Codes of 1853. How then did an avowed racist and Southern sympathizing politician from Murphysboro, in the decidedly Southern (in culture, politics, ideology, and geography) section of Illinois, go on to become a staunch supporter of both the Union and the Republican Party? Logan led quite the remarkable and often times contradictory life. Many factors contributed to his transformation including Logan’s political ambition and his war experiences, yet something acted as a catalyst for this transformation. The search for the “real” Logan is problematic due to the dearth of non-partisan accounts of his life. Even letters and unpublished materials bear the taint of clearly visible political overtones. As noted by James Jones in Black Jack, “No balanced biography of Logan exists.”2 However, by searching through the historical works of John Logan himself, his wife Mary, the various primary documents, articles and literature, and especially the works by prominent Logan historians such as James Jones we can gain a better understanding of Logan’s transformation. To understand John Logan, one must understand the nature of his upbringing. The first settlers moving westward into Illinois had come predominantly to the southern part of the state. -

Vardeman Military Service Records 1758-1783

All Vardeman War Service References 1758-1783 Last Updated May 10, 2020 1:00PM 120. May 9, 1758 Military Records, Robert Baber correspondence to George Washington, Timothy Dalton testimony regarding William Vardeman, Sr.’s (William Vardeman I), involvement in the Indian raid of May 8, 1758 Bedford Co., VA, Staunton River. Source: George Washington Papers, Library of Congress 1744-1799, Series 4, General Correspondence Source: Transcription of George Washington Papers by David Vardiman March 22, 2020 121. Apr. - May 1758 Military records, The proceedings of a Council of Officers held at Fort Loudoun, April 24, 1758. Officers present; Colonel George Washington, President, Captain Lieut. Bullitt, Lieut. King, Lieut. Thompson, Lieut. Roy, Lieut. Campbell, Lieut Buckner, Lieut. Smith, Ensign Russell; Brigadier General Forbes; Signed by Geo: Washington, Thos: Bullitt, John Campbell, John King, Mord:i Buckner, Nath:l Thompson, Chas: Smith, Ja:s Roy, Henry Russell Minutes of meeting; Mentions John Wheeler, Rob:t Dalton, Henry Wooddy, William Hall, William Vardeman, Senr. (William Vardeman I), Richard Thompson. Regarding Indian raid of May 8, 1758, Staunton River, VA Source: Colonial Soldiers of the South, 1732-1774, 1986, Murtie J. Clark, p.499. 122.June 1, 1758 January Special Court 1758, Notes for William Vardeman Sr. (William Vardeman I) and his son William Jr. (William Vardeman II) In the hope of enlisting the aid of friendly Cherokees and Catawbas in the struggle against the French and their Indian allies, Virginia Governor Dinwiddie appointed Col. William Byrd and Col. Peter Randolph to visit the two nations and negotiate a treaty. In the summer of 1756, the two tribes agreed to furnish 500 warriors in return for the erection of a fort to protect their wives and children from the northern Indians. -

S13302 Joseph Hall

Southern Campaign American Revolution Pension Statements & Rosters Pension Application of Joseph Hall S13302 Transcribed and annotated by C. Leon Harris [Punctuation partly corrected.] State of Kentucky } Lincoln County Sct } On this 24th Day of December 1832 personally appeared in open Court before the Justices of the Lincoln County Court now sitting, the same being a court of record established by the Constitution & Laws of the state of Kentucky, Joseph Hall a resident of the said County of Lincoln & state of Kentucky aged sixty eight years – who being first Duly Sworn according to Law, Doth on his oath make the following Declaration in order to obtain the benefit of the act of Congress passed 7th of June 1832 He states that he entered the service of the United States in the Virginia Militia, under the following named officers & served as herein stated He states that in the month of May 1781 he entered the service as a Draft in the County of Lincoln & District of Kentucky, (Then an Integral part of the state of Virginia) under Col Benjamin Logan. John Logan was the acting Capt. though he was called Lieutenant Colonel and they were ordered to march to Harrodsburg in the same county Twenty one miles Distant from Logans Fort in Lincoln County [1 mi W of present Stanford], for the purpose of moving the powder Magazine from Harrodsburg from Logans Fort, which had lately been brought to that place from the State of Virginia. Harrodsburg being at that time menaced by the Indians, who were at war with the United States & not being considered tenable against a strong force. -

Legends-And-Lies-The-Real-West-By-Bill

Henry Holt and Company, LLC Publishers since 1866 175 Fifth Avenue New York, New York 10010 www.henryholt.com Henry Holt® and ® are registered trademarks of Henry Holt and Company, LLC. Copyright © 2015 by Warm Springs Productions, LLC and Life of O’Reilly Productions All rights reserved. Distributed in Canada by Raincoast Book Distribution Limited Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available ISBN: 978-1-62779-507-4 Henry Holt books are available for special promotions and premiums. For details contact: Director, Special Markets. First Edition 2015 Interior Design by Nancy Singer Endpaper map by Jeffrey L.Ward Photo research and editing provided by Liz Seramur, with assistance from Nancy Singer, Emily Vinson, and Adam Vietenheimer Jacket art credits: Background and title logo courtesy of FOX NEWS CHANNEL; Denver Public Library, Western History Collection/Bridgeman Images; Chappel, Alonzo (1828–87) (after)/Private Collection/Ken Welsh/Bridgeman Images; Private Collection/ Peter Newark Western Americana/Bridgeman Images; Private Collection/Bridgeman Images; Universal History Archive/UIG/Bridgeman Images Interior art credits appear on pages 293–94. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0_Frontmatter_Final.indd 4 2/6/15 10:44 AM CONTENTS Introduction by Bill O'Reilly 1 Daniel Boone Traitor or Patriot? 4 David Crockett Capitol Hillbilly 24 Kit Carson Duty Before Honor 44 Black Bart Gentleman Bandit 70 Wild Bill Hickok Plains Justice 90 v 0_Frontmatter_Final.indd 5 2/6/15 10:44 AM vi Bass Reeves The -

Historic Families of Kentucky. with Special Reference to Stocks

NYPL RESEARCH LIBRARIES 3 3433 08181917 3 Historic Families of Kentucky. WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO STOCKS IMMEDIATELY DERIVED FROM THE VALLEY OF VIRGINIA; TRACING IN DETAIL THEIR VARIOUS GENEALOGICAL CONNEX- IONS AND ILLUSTRATING FROM HISTORIC SOURCES THEIR INFLUENCE UPON THE POLITICAL AND SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT OF KENTUCKY AND THE STATES OF THE SOUTH AND WEST. BY THOMAS MARSHALL GREEN. No greater calamity can happen to a people than to break utterly with its past. —Gladstone. FIRST SERIES. ' > , , j , CINCINNATI: ROBERT CLARKE & CO 1889. May 1913 G. brown-coue collection. Copyright, 1889, Bv Thomas Marshall Green. • • * C .,.„„..• . * ' • ; '. * • . " 4 • I • # • « PREFATORY. In his interesting "Sketches of North Cai-olina," it is stated by Rev. W. H. Foote, that the political principle asserted by the Scotch-Irish settlers in that State, in what is known as the "Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence," of the right to choose their own civil rulers, was the legitimate outgrowth of the religious principle for which their ancestors had fought in both Ireland and Scotland—that of their right to choose their own re- ligious teachers. After affirming that "The famous book, Lex Rex, by Rev. Samuel Rutherford, was full of principles that lead to Republican action," and that the Protestant emigrants to America from the North of Ireland had learned the rudiments of republicanism in the latter country, the same author empha- sizes the assertion that "these great principles they brought with them to America." In writing these pages the object has been, not to tickle vanity by reviving recollections of empty titles, or imaginary dig- or of wealth in a and nities, dissipated ; but, plain simple manner, to trace from their origin in this country a number of Kentucky families of Scottish extraction, whose ancestors, after having been seated in Ireland for several generations, emigrated to America early in the eighteenth century and became the pioneers of the Valley of Virginia, to the communities settled in which they gave their own distinguishing characteristics. -

Journal of the Lycoming County Historical Society, Fall 1997

i+793 The JOURNAL ofthe &'omiw#6o...@ ht.«{.«raga.y VOLUMEXXXVll FALL NUMBER ONE 1997 B a MUSEUM STAFF THE Director . Sandra B. Rife JOURNAL Administrative Assistant . Canola Storrs ofthe Collections Assistant(contract) Gary W.Parks INCOMING COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY Museum Store Manager Grace E. Callahan Bookkeeper Martha Spring Published arm ally {n Williamsport, Pe?tttsylula tba Floor Care (contract) . Horace James Museum 858 West Fourth Street Week-end Worker Marietta Zarb Telephone(717)326-3326 MUSEUM VOLUNTEERS BOARDOFTRUSTEES ? Penelope Austin Robert Feerrar SusanKelly Robert Paulhamus Dr. John F.Piper, Jr. Nancy Baker Heather Finnicle EliseKnowlden Beth Peet RudyBennage Grace Fleming W.J. Kuhns Dr. Lame Pepperman John L.Bruch,Jr. Anne Benson CathyFlook Dorothy Lechner Desiree Phillips Nancy Stearns Dorothy Berndt Gary Fogelman Harry Lehman Elizabeth Potter Virginia Borek May Francis RobinLeidhecker Charles Protasio William H. Hlawkes,lll james Bressler Peg Furst FrancesLevegood David Ray jack Buckle Marion Gamble Margaret Lindemuth Kim Reighard Art Burdge Patricia Gardner Pastor Robert Logan Amy Rider Alecia Burkhart Ron Gardner Mary Ellen Lupton jenni Rowley BOARDOFGOVERNORS Adehna Caporaletti Martin Gina Dorothy Maples Carol E. Serwint Amy Cappa Marv Guinter joy Mccracken Mary Sexton Michael bennett Robert Compton Fran Haas Bruce Miller Connie Crane Arlene Hater Robert Morton Mark Stamm JESS P. HACKENBURG 11, President Shirley Crawley Mary JaneHart Erin Moser Dr. Arthur Taylor BRUCE C. BUCKLE, Ffrsf Vice P7'eside71f Helen Dapp Adam Hartzel Kendra Moulthrop [)avid Taylor joni Decker Kathy Heilman Erica Mulberger Mary Louise Thomas ROBERT E. KANE, JR., 2nd I/ice P7esfdefzf Ruth Ditchfield Amy Heitsenrether Alberta Neff Mary E. -

“Traveling Thru Our Heritage, One Marker at a Time”

LINCOLN COUNTY KENTUCKY HERITAGE HIGHWAY Lincoln County Fiscal Court (Tourism) 102 E. Main “Traveling Thru Our Heritage, Stanford, KY 40486 (606) 365-2533 www.lincolnky.com One Marker at a Time” Stanford Hustonville Alcorn Homestead - Stanford Crab Orchard Lincoln County is one of the original three counties of Kentucky. Founded in 1780, you can experience our rich history as you travel the highways 45 miles south of Lexington and scenic byways. 32 miles north of Danville 25 miles west of I-75 - Mt. Vernon Wilderness Road Marker Printed in cooperation Dedication June 2005 with Kentucky Tourism 7 1 2 3 4 5 6 8 9 1 Traveler’s Rest 7 Lincoln County 13 PFC William B. Baugh, USMC Location: US 127 & Hwy 300 Location: Stanford, Courthouse lawn Location: Hustonville, 1 mi. SW of McKinney at Area Site of home of Isaac Shelby, first and fifth governor. Kentucky was made into Lincoln, Jefferson, Fayette counties. Reserve Squad, 3305 Highway 198 Stanford named and made county seat, 1786. Records in This Congressional Medal of Honor recipient risked his life 2 Capt. George Givens courthouse from 1781, oldest in the state. to spare serious injuryto others en route from Koto-ri to Location: Jct. KY 1273 & US 150 Hagaru-ri, Korea. Homesite and grave. 40 years service to his country. He received 8 County Named, 1780 military land grant, 1781. Location: Stanford, Courthouse lawn, Business US 150 & KY 14 Ottenheim 1247 Location: Halls Gap, US 27 & KY 643 3 Birthplace of Naval Aviation Pioneer For Benjamin Lincoln, 1733-1810. Born Mass. In War of Revolution A German-Swiss settlement, 4 miles southeast, started by Location: 1 mi. -

External Relations of the Ohio Valley Shawnees, 1730-1775

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1992 "Mischiefs So Close to Each Other": External Relations of the Ohio Valley Shawnees, 1730-1775 Courtney B. Caudill College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Caudill, Courtney B., ""Mischiefs So Close to Each Other": External Relations of the Ohio Valley Shawnees, 1730-1775" (1992). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625770. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-rvw6-gp52 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "MISCHIEFS SO CLOSE TO EACH OTHER1': EXTERNAL RELATIONS OF THE OHIO VALLEY SHAWNEES, 1730-1775 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Courtney B. Caudill 1992 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts . C cuac&J?/ Courtney B. Caudill Approved, May 1992 J kXjlU James Axtell >hn Sell Michael McGiffert For Mom: Thanks, Easter Bunny. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS............................................... v PREFACE............ vi ABSTRACT............................................................ ix WALKING THE PATHS.......................... 2 CHAPTER I. BUILDING THE WEGIWA: THE 1730S TO THE SEVEN YEARS' WAR..13 CHAPTER II. -

Annals of Augusta County, Virginia

r AMALS OF AUGUSTA -UNTY , YIRGIUIA by Jos, A, Y/addell 9^5-591 ANNALS Augusta County, Virginia JOS. A. WADDELL. SUPPLKIVIENT. J. W. RANDOLPH & ENGLISH, Publishers, RICHMOND, VA. 1888. PRKKACK. The chief object of this Supplement is to preserve some ac- count of many pioneer settlers of Augusta county and their immediate descendants. It would be impossible, within any reasonable limits, to include the existing generation, and hence the names of living persons are generally omitted. The writer regrets that he cannot present here sketches of other ancient and worthy families, such as the Andersons, Christians, Hamiltons, Kerrs, McPheeterses, Millers, Pattersons, Pilsons, Walkers, etc. The genealogies of several of the oldest and most distinguished families— Lewis, Preston, Houston, etc. —are omitted, because they are given fully in other publications. For much valuable assistance the writer is indebted to Jacob Fuller, Esq. , Librarian of Washington and Lee University, and especially to Miss Alice Trimble, of New Vienna, Ohio. J. A. W. Staunton, Va., March, 1888. 166310 CONTKNTS. Early Records of Orange County Court 381 The Rev. John Craig and His Times 388 Gabriel Jones, the King's Attorney 392 The Campbells . , , 396 The Bordens, McDowells and McClungs 398 The Browns 400 Mrs. Floyd's Narrative 401 The Floyds 404 The Logans 404 Colonel William Flipming 406 The Estills 407 Colonel William Whitley 408 The Moffetts 408 The Aliens 410 The Trimbles 411 Fort Defiance 413 The Smiths 413 The Harrisons, of Rockingham 415 The Alexanders and Wilsons 416 The Raid upon the Wilson Family 417 The Robertsons 420 Treaties with Indians 421 The McKees 422 The Crawfords. -

Longhunter, Southern Kentucky Genealogical Society Newsletter Volume 18, Number 1 Kentucky Library Research Collections Western Kentucky University, [email protected]

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Longhunter, Southern Kentucky Genealogical Kentucky Library - Serials Society Newsletter Winter 1995 Longhunter, Southern Kentucky Genealogical Society Newsletter Volume 18, Number 1 Kentucky Library Research Collections Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/longhunter_sokygsn Part of the Genealogy Commons, Public History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Kentucky Library Research Collections, "Longhunter, Southern Kentucky Genealogical Society Newsletter Volume 18, Number 1" (1995). Longhunter, Southern Kentucky Genealogical Society Newsletter. Paper 112. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/longhunter_sokygsn/112 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Longhunter, Southern Kentucky Genealogical Society Newsletter by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ''''ff~. HU'~T[R ~~S" 1067 7J48 60lYth~t-n ~entvckB (5 ~n ~ ulo 91 C 0.1 Socl~lB -+-I VC>I.UMF; XVTrJ. J SSlJF:1 SOUTHERN KENTUCKY GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY P. O. Box 1782 Bowling Green , KY 42102-1782 1995 OFFICERS AND CHAIRPERSONS ***************************************************************************** President Barbara Ford, 545 Cherokee Dr., Bowling Green, KY 42103 Ph. 502 782 0889 Vice President: Gene Whicker, 1118 Nahm Dr., Bowling Green, KY 42104 Ph. 502 842 5382 Recording Secretary: Gail Miller, 425 Midcrest Dr., Bowling Green, KY 42101 P h. 502 781 1807 Corresponding Secretary Betty B. Lyne, 613 E 11TH Ave., Bowling Green, KY 42101 Ph. 502 843 9452 Treasurer Ramona Bobbitt, 2718 Smallhouse Rd., Bowling Green, KY 42104 Ph. 502 843 6918 Chaplain James David Evans, 921 Meadowlark Drive Bowling Green, KY 42103 Ph.