Public Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

06/24/2020 APPROVAL of FINANCIAL REPORTS – Financial Reports

Conrad Weiser Area School District Robesonia, PA Minutes – June 24, 2020 At 7:30 p.m., President Francis J. Kaczmarczyk called to order the regular meeting for the month of June of the Board of School Directors of the Conrad Weiser Area School District. Present for the Meeting Board Members William T. Carl Jr., James Dotzenroth, Dennis J. Manbeck, Neal McNutt, Gary G. Neider, Bret A.B. Sabold, Joshua Speirs and Francis J. Kaczmarczyk Solicitor Leah Rotenberg, Esquire School Personnel Randall A. Grove, Ryan R. Giffing, Robin L. Robertson, Jessica L. Head, Robert G. Galtere, Jonathan Holota, Nicole C. Moore, Melissa Rhoads, Christy Hoffman, William Harrison, Eric A. Lutz, William R. Knapper and Heather M. Stricker APPROVAL OF POLICY GUIDELINES – A. Motion by Kaczmarczyk, Seconded by Carl, Policy 006.1 RESOLVED, to suspend the guidelines in Policy 006.1, “Attendance at Meetings Via Electronic Communications” regarding physical attendance and prior notice by board members for the June 24, 2020 school board meeting. This resolution was duly adopted by the following vote: Aye: Carl, Dotzenroth, Manbeck, McNutt, Neider, Sabold, Speirs and Kaczmarczyk …….……….……… 8 ANNOUNCEMENTS Announcements APPROVAL OF MINUTES – A. Motion by Carl, Seconded by Neider, Minutes RESOLVED, that the reading of the Minutes of the regular meeting of the Board of School Directors for the month of May held on May 20, 2020 be approved by voice vote. This resolution was duly adopted by the following voice vote: Aye: Carl, Dotzenroth, Manbeck, McNutt, Neider, Sabold, Speirs and Kaczmarczyk …….……….……… 8 -1- 06/24/2020 APPROVAL OF FINANCIAL REPORTS – Financial Reports A. Motion by Sabold, Seconded by Carl, RESOLVED, that the financial reports be approved, as presented. -

In Search of the Indiana Lenape

IN SEARCH OF THE INDIANA LENAPE: A PREDICTIVE SUMMARY OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMPACT OF THE LENAPE LIVING ALONG THE WHITE RIVER IN INDIANA FROM 1790 - 1821 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY JESSICA L. YANN DR. RONALD HICKS, CHAIR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA DECEMBER 2009 Table of Contents Figures and Tables ........................................................................................................................ iii Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 Research Goals ............................................................................................................................ 1 Background .................................................................................................................................. 2 Chapter 2: Theory and Methods ................................................................................................. 6 Explaining Contact and Its Material Remains ............................................................................. 6 Predicting the Intensity of Change and its Effects on Identity................................................... 14 Change and the Lenape .............................................................................................................. 16 Methods .................................................................................................................................... -

POINT PLEASANT 1774 Prelude to the American Revolution

POINT PLEASANT 1774 Prelude to the American Revolution JOHN F WINKLER ILLUSTRATED BY PETER DENNIS © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CAMPAIGN 273 POINT PLEASANT 1774 Prelude to the American Revolution JOHN F WINKLER ILLUSTRATED BY PETER DENNIS Series editor Marcus Cowper © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 The strategic situation The Appalachian frontier The Ohio Indians Lord Dunmore’s Virginia CHRONOLOGY 17 OPPOSING COMMANDERS 20 Virginia commanders Indian commanders OPPOSING ARMIES 25 Virginian forces Indian forces Orders of battle OPPOSING PLANS 34 Virginian plans Indian plans THE CAMPAIGN AND BATTLE 38 From Baker’s trading post to Wakatomica From Wakatomica to Point Pleasant The battle of Point Pleasant From Point Pleasant to Fort Gower THE AFTERMATH 89 THE BATTLEFIELD TODAY 93 FURTHER READING 94 INDEX 95 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com 4 British North America in1774 British North NEWFOUNDLAND Lake Superior Quebec QUEBEC ISLAND OF NOVA ST JOHN SCOTIA Montreal Fort Michilimackinac Lake St Lawrence River MASSACHUSETTS Huron Lake Lake Ontario NEW Michigan Fort Niagara HAMPSHIRE Fort Detroit Lake Erie NEW YORK Boston MASSACHUSETTS RHODE ISLAND PENNSYLVANIA New York CONNECTICUT Philadelphia Pittsburgh NEW JERSEY MARYLAND Point Pleasant DELAWARE N St Louis Ohio River VANDALIA KENTUCKY Williamsburg LOUISIANA VIRGINIA ATLANTIC OCEAN NORTH CAROLINA Forts Cities and towns SOUTH Mississippi River CAROLINA Battlefields GEORGIA Political boundary Proposed or disputed area boundary -

Read the Introduction

The land west of the Susquehanna River and north of the Blue Mountains was the new frontier in 1750 Colonial America. It was a virgin unspoiled land of oak, maple, and pine forests with seemingly endless supplies of deer, bear, and turkey. It was a land of untold riches and unlimited opportunity. By treaty with William Penn this was Indian Territory. Intrepid and adventurous European settlers just couldn’t resist the opportunity and started to move into the area in the 1740s and throughout the 1750s. The Native Americans continually complained and the Provincial Government responded by arresting trespassers, removing them from their illegally claimed lands and burning their cabins. This would not deter the settlers and they moved further into Shermans Valley and then north into Tuscarora Valley. 1 At the entrance to Shermans Valley was a trader’s cabin and tavern owned by George Croghan. Croghan had been legally trading with the Indians for many years and was highly respected by them. Some of the meetings between the Indians and the Provincial Officials were held at his homestead in Pennsboro and others at his cabin on top of Blue Mountain, then called Kittatinny. He later sold the mountain property to William Sterritt. Today this gateway to the north and west retains his name and is known as Sterrets Gap. Later in history the property was owned by James Buchannan, the 15th President of the United States. Traders licensed by the government could legally enter the territory and conduct business with the Indians. These traders followed old Indian trails that became the main routes of travel in the new territory. -

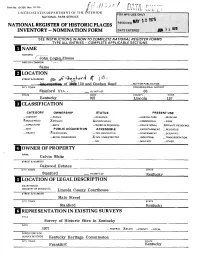

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC ^-CLogar^/House I LOCATION STREET & NUMBER U. VJUOlltUl -LXUctU CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Stanford (}{<-• _ VICINITY OF 05 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Kentucky 021 Lincoln 137 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM XBUILDINGIS) X.PRIVATE X.UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS — EDUCATIONAL -XPRIVATE RESIDENCE _SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT 2ilN PROCESS — YES: RESTRICTED _ GOVERNMENT _ SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY _ OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Calvin„ , . White„„ STREET & NUMBER Oakwood Estates CITY, TOWN STATE Stanford VICINITY OF Kentucky LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Lincoln QOUnty STREETS NUMBER Main Street CITY, TOWN STATE Stanford Kentucky REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Survey of Historic Sites in Kentucky DATE 1971 —FEDERAL XSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Kentucky Heritage Commission CITY, TOWN STATE Frankfort Kentucky DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE .EXCELLENT X.DETERIORATED UNALTERED JXORIGINALSiTE .GOOD _RUINS X.ALTERED _MOVED DATE. .FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The John Logan House is located on Logan1 s Creek at the mouth of St. Asaph's Branch. The house is situated a mile east of the center of Stanford on the old east-west road between Stanford and Rowland on U.S. Highway 150, known as the Old Wilderness Road. -

Conrad Weiser Papers 0700 Finding Aid Prepared by Sarah Newhouse and Anna Baechtold Georgi

Conrad Weiser papers 0700 Finding aid prepared by Sarah Newhouse and Anna Baechtold Georgi. Last updated on November 09, 2018. Historical Society of Pennsylvania November 2011 Conrad Weiser papers Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 4 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Bibliography...................................................................................................................................................8 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 9 - Page 2 - Conrad Weiser papers Summary Information Repository Historical Society of Pennsylvania Creator Weiser, Conrad, 1696-1760. Creator Weiser, Samuel, 1735-1794. Title Conrad Weiser papers Call number 0700 Date [inclusive] 1741-1783 Extent 1.33 linear feet (2 boxes, 4 volumes) Language English Language of Materials note Materials are in English and German. Mixed materials (00006990)1 [Volume] Mixed materials -

The German Emigration from New York Province Into Pennsylvania

^ENEAUOGV COLLECnriON penne^lpania: THE GERMAN INFLUENCE IN ITS SETTLEMENT AND DEVELOPMENT. B IRarrative an5 Critical Distort. PREPARED BY AUTHORITY OF THE PENNSYLVANIA-GERMAN SOCIETY. C e c -' \ <P • • . • "^ O €- A t v^ ^ . V PARt V. THE GERMAN EMIGRATION FROM NEW YORK PROVINCE INTO PENNSYLVANIA. PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY. 1899. ^A^A^ . Id ' fsr^^ c^-i^ o^^^—tLJ (3erman lEmtgration from Bew ^oxh province into Ipenns^Ivanm Part V. of A Narrative and Critical History, PREPARED AT THE REQUEST OF The Pennsylvania-German Society BY REV. MATTHIAS HENRY RICHARDS, D.D. PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE IN MUHLENBERG COLLEGE OF THE EVANGELICAL LUTHERAN CHURCH IN ALLENTOWN ; EDITOR OF THE " CHURCH LESSON leaf" AND "the helper" ; CHAIRMAN OF THE "GENERAL COUNCIL SUNDAY-SCHOOL committee" ; EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE " LUTHERAN," " CHURCH MESSENGER," ETC.; AUTHOR OF THE " BEGINNEr's CATECHISM," ETC., ETC. LANCASTER, PA 1899 Copyright by Pennsylvania German Society. 1899. All rights reserved. Illustrations by Julius F. Sachse. 1162741 CHAPTER I. THE GERMAN EMIGRATION FROM NEW ^^ YORK PROVINCE INTO PENNSYLVANIA. A Preliminary Resume.' ^ (^JT'HE task assigned to me is to ^ V^"gS^^X ^ present the features of what may, in some respects, be called an episode of that migra- tion of Palatines which took place in 1710, and which sought its hoped for resting place in New ^& ^'^'^JfUl^:^)^ York Province, only to find the rather a prison house and a land of bondage. In other respects, this subsequent migration to Penn- sylvania, though scanty as to numbers, was influential to no inconsiderable degree and deserves therefore a con- sideration far beyond that which should be accorded iThe sudden decease of the Rev. -

The Emergence and Decline of the Delaware Indian Nation in Western Pennsylvania and the Ohio Country, 1730--1795

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The Research Repository @ WVU (West Virginia University) Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2005 The emergence and decline of the Delaware Indian nation in western Pennsylvania and the Ohio country, 1730--1795 Richard S. Grimes West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Grimes, Richard S., "The emergence and decline of the Delaware Indian nation in western Pennsylvania and the Ohio country, 1730--1795" (2005). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 4150. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/4150 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Emergence and Decline of the Delaware Indian Nation in Western Pennsylvania and the Ohio Country, 1730-1795 Richard S. Grimes Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Mary Lou Lustig, Ph.D., Chair Kenneth A. -

Muhlenberg County Heritage Volume 6, Number 1

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Muhlenberg County Heritage Kentucky Library - Serials 3-1984 Muhlenberg County Heritage Volume 6, Number 1 Kentucky Library Research Collections Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/muhlenberg_cty_heritage Part of the Genealogy Commons, Public History Commons, and the United States History Commons This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Muhlenberg County Heritage by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MUHLENBERG COUNTY HERITAGE ·' P.UBLISHED QUARTERLY THE MUHLENBERG COUNTY GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY, CENTRAL CITY LIBRARY BROAD STREET, CENTRAL CITY, KY. 42J30 VOL. 6, NO. 1 Jan., Feb., Mar., 1984 ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ During the four weeks of November and first week of December, 1906, Mr. R. T. Martin published a series of articles in The Record, a Greenville newspaper, which he titled PIONEERS. Beginning with this issue of The Heritage, we will reprint those articles, but may not follow the 5-parts exactly, for we will be combining some articles in whole or part, because of space requirements. For the most part Mr. Martin's wording will be followed exactly, but some punctuation, or other minor matters, may be altered. In a few instances questionable items are followed by possible corrections in parentheses. It is believed you will find these articles of interest and perhaps of value to many of our readers. PIONEERS Our grandfathers and great-grandfathers, many of them, came to Kentucky over a cen tury a~o; Virginia is said to be the mother state. -

Feasibility Study on a Potential Susquehanna Connector Trail for the John Smith Historic Trail

Feasibility Study on a Potential Susquehanna Connector Trail for the John Smith Historic Trail Prepared for The Friends of the John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail November 16, 2009 Coordinated by The Bucknell University Environmental Center’sNature and Human Communities Initiative The Susquehanna Colloquium for Nature and Human Communities The Susquehanna River Heartland Coalition for Environmental Studies In partnership with Bucknell University The Eastern Delaware Nations The Haudenosaunee Confederacy The Susquehanna Greenway Partnership Pennsylvania Environmental Council Funded by the Conservation Fund/R.K. Mellon Foundation 2 Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 3 Recommended Susquehanna River Connecting Trail................................................................. 5 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 6 Staff ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Criteria used for Study................................................................................................................. 6 2. Description of Study Area, Team Areas, and Smith Map Analysis ...................................... 8 a. Master Map of Sites and Trails from Smith Era in Study Area........................................... 8 b. Study -

2009 Inductions

2009 Inductions: Kenneth Riegel is a world-renowned tenor Patrick Gelsinger heads EMC Infor- who has appeared in opera, concerts, and mation Infrastructure Products as its Presi- recitals all over the world. He began his dent and Chief Operating Officer. Previous- career in 1965 at the Santa Fe Opera and has ly, he held various executive and technical since performed frequently at the positions for Intel Corporation, including Metropolitan Opera, the New York City Senior Vice President and Co-General Man- Opera as well as operas in Chicago, San ager of Intel’s Digital Enterprise group, Francisco, Vienna, Salzburg, Rome, La Scala Chief Technology Officer, and head of In- in Milan, Florence, Bologna, London, Berlin, tel’s Desktop Products Group. He was first Hamburg, Munich, Madrid, Barcelona, ever CTO, the youngest Vice-President in Athens, Moscow, Geneva, and Brussels. Intel’s history, and he holds six patents in the areas of computer architecture and com- munications. He led seminal programs for Mr. Riegel has appeared in the film versions Intel including the 80386, 80486, Pentium of Don Giovanni and Boris Godunov and has Pro and most recently the Nehalem micro- won several Grammy awards for his processor. recordings as well as other international music awards. He has given master classes in voice in the United States and throughout During his years at Conrad Weiser, Mr. Gel- Europe. singer attended classes at the Berks Career and Technology Center and concentrated his study on electronics. Mr. Gelsinger earned Ken Riegel began his musical education at an associate’s degree from Lincoln Tech- West Chester and continued his studies at the nical Institute, a bachelor’s degree from Manhattan School of Music and the Santa Clara University, and a master’s de- Metropolitan Opera Studio. -

Early Cold War and American Indians: Minority Under Pressure by Jaakko Puisto

AMERICAN STUDIES jOURNAL Number 46/Winter 2000 ISSN: 1433-S239 DMS,OO ---- - AMERICAN STUDIES jOURNAL Number 46 Winter 2000 Native Atnericans: Cultural Encounters ISSN: 1433-5239 Editor's Note Lutherstadt Wittenberg, October 2000 Two short notes about our subscription policy: Many of our subscribers have asked if it was necessary to Dear Readers, send the postcards attached to every issue of the American Studies Journal to renew the subscription. This, of course, is Germans are truly fascinated with Native Americans. As not necessary. We only need a notification if your mailing children they play Cowboy and Indian, later in life they address has changed. read or watch about the adventures of Winnetou (of whom, by the way, Americans have never heard) or Hawkeye. Due to the high cost of sending the American Studies Radebeul and Bad Seegeberg are places the modern pilgrim Journal to international subscribers, we are forced to increase of Native American fascination has to visit, the former as the subscription rate for mailing addresses outside of the birthplace of Karl May, the latter as the place where Germany. Starting with the 2001-subscription, the Winnetou and Old Shatterhand ride into the sunset anew international rates will be as follows: every Summer. For Germans and most other Europeans, -for subscribers in Europe (excluding Germany): Indians symbolize freedom, grace, tradition and being one 10,00 DM per subscription plus 15,00 DM postage. Every with nature. However, these images of Native Americans additional subscription costs 3,00 DM rest on stereotypes of pre-20'h century encounters with -for subscribers outside of Europe: 10,00 DM per European settlers and are as distorted as they are a European subscription plus invention.