Dialogue of the Deaf – Foreign Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Egyptian Regime Begins US-Backed Talks with Opposition Parties

Egyptian Regime Begins US-Backed Talks With Opposition Parties By Patrick O'Connor Region: Middle East & North Africa Global Research, February 07, 2011 World Socialist Web Site 7 February 2011 The Obama administration has backed negotiations between the Mubarak regime and several Egyptian opposition parties, including the Muslim Brotherhood. Vice President Omar Suleiman, who led the discussions, which began yesterday, is now being groomed by Washington and its allies to head a military-dominated “transitional” government tasked with disorienting and, if necessary, crushing the mass uprising of Egyptian workers and young people. Suleiman met with representatives of the Muslim Brotherhood, who repudiated previous pledges not to enter into talks with the government until Mubarak resigned. According to the Guardian, the Islamists absurdly declared that they “did not regard the meeting as negotiations but as an opportunity to hear the government’s position.” Suleiman also spoke with members of several political parties such as Wafd and Tagammu that were afforded semi-legal status and a small number of parliamentary seats under Mubarak’s dictatorship. Also included was a committee supposedly representing pro-democracy youth groups, independent legal experts and businessman Naguib Sawiris. Mohammed ElBaradei, the former head of the UN nuclear weapons inspection program, said he had not been invited to the talks. However, a member of his National Association for Change group participated who was described by Al Jazeera as ElBaradei’s representative. -

Timeline: Egypt's Political Transition

DOCUMENTS Timeline: Egypt’s Political Transition Compiled by Ghazala Irshad April 6, 2008: Factory workers attempt to stage January 1-3, 2011: Following a deadly New Year’s a general strike over low wages and high food church bombing in Alexandria, Coptic Christians prices in the Nile Delta city of Mahalla. Police in Alexandria and Cairo throw rocks and set fire open fire and arrest hundreds. The incident to vehicles in protest of the government’s failure to pushes the nascent April 6 Youth Movement guarantee their security. to demonstrate alongside the workers in oppo- sition to President Hosni Mubarak’s regime January 14, 2011: In Tunisia, ten days after throughout Egypt. Bouazizi’s death, Ben Ali resigns the presidency and flees to Saudi Arabia, bringing an end to his February 24, 2010: Mohamed ElBaradei, former twenty-three-year rule. director general of the International Atomic Energy Agency, returns to Egypt to a hero’s January 25, 2011: Tens of thousands of Egyptians, welcome, raising the possibility that he will run responding to calls for anti-government protests for president; he launches the National Associa- on national Police Day, stage unprecedented dem- tion for Change, a reformist group, with several onstrations in Cairo’s Tahrir Square and other other prominent democracy activists, including Egyptian urban centers. Riot police attempt to journalist Hamdi Qandil and political analyst disperse them using batons, tear gas, and water Hassan Nafaa. cannons. Two protesters in Suez and a police offi- cer in Cairo are killed. June 6, 2010: Police beat to death Khaled Said, a twenty-eight-year-old computer programming January 27, 2011: Police clash with protesters graduate, on a street in Alexandria. -

English of Scientific Class at Founded UNESCO Serves Cross the Commander’S Aliyev Prize(2009)

Bibliotheca Alexandrina Annual ReportJuly 2009-June 2010 WHO WE ARE 2009/2010 www.bibalex.org © (2010) Bibliotheca Alexandrina NON-COMMERCIAL REPRODUCTION Information in this booklet has been produced with the intent that it be readily available for personal and public non-commercial use and may be reproduced, in part or in whole and by any means, without charge or further permission from the Bibliotheca Alexandrina. We ask only that: • Users exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced; • Bibliotheca Alexandrina be identified as the source; and • The reproduction is not represented as an official version of the materials reproduced, nor as having been made in affiliation with or with the endorsement of the Bibliotheca Alexandrina. Editing Publishing Department Design & Layout Gihan Aboelnaga 800 Copies MISSION STATEMENT To be a center of excellence for the production and dissemination of knowledge, and a place of dialogue and understanding between cultures and peoples. OBJECTIVES To be , • the World s Window on Egypt; , • Egypt s Window on the World; • an Instrument for Rising to the Challenges of the Digital Age; and • a Center for Dialogue between Peoples and Civilizations. CONTENTS Introduction 7 Board of Trustees 11 Advisory Board 30 Meet the Management 49 Consultants & Special Advisors 103 2009/2010 www.bibalex.org Introduction ccording to Presidential Decree No.76 for the year 2001, Article 2, the New Library of Alexandria is governed by a Council of Patrons, a Board of Trustees (BoT), and a Director. The Council of Patrons includes Heads of States, royalty and other dignitaries. TheA BoT, on the other hand, is the decision-making power on the matters of the Library, vested with all the authority to run the affairs of the Library, with over half of its members being eminent non-Egyptians, thereby reinforcing the view that the Library is an Egyptian entity with an international orientation. -

An Analysis Of

AUTHORITARIAN RESPONSE TO POPULAR REVOLUTIONS: AN ANALYSIS OF THE PARANOID PERSONALITY IN LEADERSHIP DECISION-MAKING By DAMIAN RAMIREZ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY School of Politics, Philosophy, & Public Affairs DECEMBER 2016 © Copyright by DAMIAN RAMIREZ, 2016 All Rights Reserved © Copyright by DAMIAN RAMIREZ, 2016 All Rights Reserved To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the dissertation of DAMIAN RAMIREZ find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. _______________________________ Martha L. Cottam, Ph.D., Chair _______________________________ Thomas Preston, Ph.D. _______________________________ Otwin Marenin, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I could probably fill an equivalent amount of pages of this dissertation just thanking the people who have helped, or prodded, me to reach this point in my life to where I am writing an acknowledgements section to a dissertation. However, no matter the amount of pages I could write, they would have to begin with thanking my committee chair Dr. Martha Cottam and other committee members Dr. Otwin Marenin and Dr. John Thomas Preston for the guidance that has helped me get to this point. Even if I never step inside a classroom again, I am a better person for having learned how to think analytically from them. Just as important is my indebtedness to Dr. Nicholas Lovrich for his mentorship while I was an undergraduate at Washington State University considering going to a graduate school and his continued mentorship after I had decided to pursue further studies while remaining at WSU. -

Political Opposition and Authoritarian Rule in Egypt

Holger Albrecht Political Opposition and Authoritarian Rule in Egypt Dissertation Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Sozialwissenschaften in der Fakultät für Sozial- und Verhaltenswissenschaften der Eberhard-Karls Universität Tübingen 2007 Promotionserklärung Hiermit erkläre ich, dass ich diese Dissertation nicht bereits früher als Prüfungsarbeit bei einer akademischen oder staatlichen Prüfung verwendet habe oder mit ihr oder einer anderen Dissertation bereits einen Promotionsversuch unternommen habe. Tübingen, 29. Oktober 2007 (Holger Albrecht) Urheberschaftserklärung Hiermit erkläre ich, dass ich diese Dissertation selbständig verfasst, nur die angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel benutzt und wörtlich oder inhaltlich übernommene Stellen als solche gekennzeichnet habe. Tübingen, 29. Oktober 2007 (Holger Albrecht) Contents Note on Transliteration 1 List of Abbreviations 2 Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 7 Chapter 1: The Authoritarian State in the Middle East 13 1.1. Authoritarian vs. Patrimonial Regimes 14 1.2. ‘Liberalized Authoritarianism’ Reconsidered 27 1.3. Regime Stability and the Dynamics of Authoritarian Power Maintenance 34 Chapter 2: Political Participation in the Middle East: Authoritarianism from Below 41 2.1. Concept Traveling: Political Participation under Authoritarianism 41 2.2. Channels of Political Participation in the Middle East 49 2.3. Contentious Political Participation: The Civil Society Argument and Social Movement Theory 59 Social Movement Theory 59 The Civil Society Argument 63 1 Chapter 3: Political Opposition under Authoritarianism 71 3.1. Towards a Concept of Political Opposition 72 3.2. The Systemic Context: Opposition under Democracy vs. Authoritarianism 79 3.3. Patterns of Opposition under Authoritarianism in the Middle East 89 The Representation Function 93 The Legitimacy Function 93 The Channeling Function 94 The Moderation Function 94 Chapter 4: Mapping the Landscape of Contentious Politics in Egypt 97 4.1. -

MIDDLE Eastbriefing

MIDDLE EAST Briefing Cairo/Brussels, 30 September 2003 THE CHALLENGE OF POLITICAL REFORM: EGYPT AFTER THE IRAQ WAR This briefing is one of a series of occasional ICG briefing papers and reports that will address the issue of political reform in the Middle East and North Africa. The absence of a credible political life in most parts of the region, while not necessarily bound to produce violent conflict, is intimately connected to a host of questions that affect its longer-term stability: Ineffective political representation, popular participation and government responsiveness often translate into inadequate mechanisms to express and channel public discontent, creating the potential for extra- institutional protests. These may, in turn, take on more violent forms, especially at a time when regional developments (in the Israeli-Palestinian theatre and in Iraq) have polarised and radicalised public opinion. In the long run, the lack of genuine public accountability and transparency hampers sound economic development. While transparency and accountability are by no means a guarantee against corruption, their absence virtually ensures it. Also, without public participation, governments are likely to be more receptive to demands for economic reform emanating from the international community than from their own citizens. As a result, policy-makers risk taking insufficient account of the social and political impact of their decisions. Weakened political legitimacy and economic under-development undermine the Arab states’ ability to play an effective part on the regional scene at a time of crisis when their constructive and creative leadership is more necessary than ever. The deficit of democratic representation may be a direct source of conflict, as in the case of Algeria. -

A New Generation of Autocracy in Egypt

A New Generation of Autocracy in Egypt JASON BROWNLEE Assistant Professor University of Texas at Austin "THE GREAT AND PROUD NATION of Egypt has shown the way toward peace in the Middle East, and now should show the way toward democracy in the Middle East."' With this injunction, U.S. President Ceorge W. Bush sought to catalyze political reform in the region's most populous state. But his bold declaration has elicited the same kinds of faux liberalization that have characterized Egyptian President Hosn) Mubarak's quar- ter-century in power. While allowing a patina of competitive politics to validate the United States' hopes, Mubarak has also confirmed his critics' worst fears. Constitutional amendments in May 2005, followed by presidential and parliamentary elections that fall, benefited Mubarak's National Democratic Party (NDP) and exposed his opponents to state-sanctioned repression. This past spring, the regime further entrenched itself, deploying a second round of amendments that doomed any chance for vibrant multi- partyism under the current president or his successor. The Egyptian elite has thus turned Bush's call on its head, embracing the mantle of reform only to enshrine its dominance beyond Hosni Mubarak's passing. Rather than blazing a new path to democracy, Egypt has embarked on the road to political dynasty recently traversed by the Assads in Syria and the Aliyevs in Azerbaijan. The lopsided battle over constitutional changes thereby signifies the Egyptian government's success at regenerating authoritarianism while again suppressing its critics. This essay recounts the latest arc of liberalization and repression. It also addresses the reasons why hereditary succession may command the tacit support of most Egyp- tian leaders, focusing on the "transitional period" of the past two years, during which autocratic rule has been rejuvenated without being reformed.' JASON BROWNLEE is an assistant professor of government at the University ofTexas at Austin and a regular visitor to Egypt. -

Egypt – EGY39263 – National Democratic Party – Family of Members – Qalubiya 7 October 2011

Country Advice Egypt Egypt – EGY39263 – National Democratic Party – Family of Members – Qalubiya 7 October 2011 1. Can you provide a brief history of the National Democratic Party? The National Democratic Party (NDP) was established by President Anwar Sadat in 1978 as a de facto successor to the previously ruling Arab Socialist Union. The NDP remained the principal political party in Egypt for next thirty years, entrenching itself in state institutions and dominating cultural and political life.1 It draws its main base of support from rural areas and public sector workers and, prior to the February 2011 uprising, claimed to have 1.9 million members. Hosni Mubarak became President and Chair of the party in 1981 following the assassination of Sadat by Islamic extremists. Under Mubarak the party was accused of maintaining power through political repression, including through the regulation of authorised political parties and civil organisations, and the arrest, detention and torture of political opponents.2 Parliamentary elections held in 2005 and 2010, in which the party won a broad majority, were marred by allegations of vote rigging and fraud.3 Following a popular uprising against the party‘s rule in February 2011, the party was dissolved by court ruling on 16 April 2011.4 Some former NDP officials have established new political parties with a view to run in upcoming parliamentary elections.5 The 2010 Political Handbook of the World states the following on the NDP: 1 ‗Egypt‘ 2010, Political Handbook of the World Online Edition, CQ Press Electronic Library http://library.cqpress.com/phw/document.php?id=phw2010_Egypt&type=toc&num=56 – Accessed 22 September 2011; ‗Guide to Egypt‘s Transition – National Democratic Party‘ (undated), Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, http://egyptelections.carnegieendowment.org/2011/09/22/national-democratic-party – Accessed 6 October 2011 2 US Department of State 2011, 2010 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, 8 April, Sec 1d. -

Mubarak-Page

A6 SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 2, 2012 SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 2, 2012 Last Days of the Pharaoh by Bradley Hope, Kindle SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 2, 2012 Single: Amazon, 2012. 48pp; Available through REGION Amazon’s cloud reader or on the Kindle/IPad/etc ‘Last Pharaoh’s’ last stand Bradley Hope, a US journalist based in Cairo who has just published Last Days of the Pharaoh, examining Egypt’s 2011 uprising, describes to Times of Oman some of the interesting facets of his e-book sojourn MEHRE ALAM [email protected] MUSCAT: This is the story of how Egypt’s ‘last Pharaoh’ fell. A lot has already been written about it. But this one throws light on some of the untold anecdotes of those 18 fateful days that reshaped Egypt’s history, and indeed the region’s. Egypt-based US journalist Bradley Hope, who has weaved his tale based on interviews with senior officials and political leaders close to Hosni Mubarak, believes that sometimes one can get to the truth — of what Bradley Hope (centre) in Libya last year, where he was reporting on the happened during a big event — only fall of Muammar Gaddafi. – Supplied picture after some time has passed by. “The pace of news in the region (Middle East) has been so fast over years as a police reporter and feature very small in the scheme of things. I the last year-and-a-half that there writer for the New York Sun before think most Egyptians are willing to hasn’t been a lot of time for look- joining an Abu Dhabi publication. -

CR1-Insidetheuprisings.Pdf

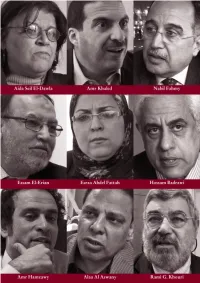

Cairo_Review_Q&A_Layout 1 27.04.11 09:06 Seite 67 The Cairo Review Interviews Inside Egypt’s uprising ew imagined such a scene, such defiance: in Tahrir Square, a million Egyptians protested with a huge banner that read “PEOPLE DEMAND REMOVAL FOF THE REGIME.” Young activists used social media tools such as Facebook to organize the first protest on January 25, the country’s Police Day. Eighteen days of mounting demonstrations later, with the country increasingly paralyzed, President Hosni Mubarak resigned after a thirty-year rule. Mohammed Bouazizi, a twenty-six-year-old street vendor in the Tunisian town of Sidi Bouzid, is the one who lit the match that ignited the revolts against dictators throughout the Arab world. His self-immolation last December 17—after a governmen t inspector confiscated his fruit and slapped him for trying to resist her authority—set off protests all over Tunisia and drove President Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali from power on January 14. Before long, uprisings also posed threats to longstanding regimes in Libya, Yemen, Bahrain, and Syria. The Arab revolutions of 2011 are a turning point in Middle East history. Why did they occur? Why now? What comes next? In the Cairo Review Interviews, nine key figures give an inside look at the causes and effects of Egypt’s uprising and discuss the challenges now facing the country and the region. Amr Khaled: How to rebuild Egypt Esraa Abdel Fattah: The new youth activism Hossam Badrawi: Revolution viewed from inside the regime Alaa Al Aswany: Artists and protests Essam El-Erian: Future of the Muslim Brotherhood Nabil Fahmy: Arab foreign policy shift Amr Hamzawy: Challenge of transition Aida Seif El-Dawla: Ongoing human rights abuses Rami G. -

Egypt Human Development Report 2010

Egypt Human Development Report 2010 Egypt Human Development Report 2010 Youth in Egypt: Building our Future Final exams coming up... He has such ...then I’ll good values... need a job to get I can wait married The Egypt Human Development Report 2010 is a major output of the Human Development Project, executed by the Institute of National Planning, Egypt, under the project document EGY/01/006 of technical cooperation with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Copyright 2010, United Nations Development Programme, and the Institute of National Planning, Egypt. The analysis and policy recommendations of this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the UNDP or the Ministry of Economic Development. The authors hold responsibility for the opinions expressed in this publication. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission or reference to this source. Concept, cover, photo montage, design, layout by Joanne Cunningham. Illustration credits All photography by Joanne Cunningham, UNDP, MDG Sailing the Nile Project. Printed by Virgin Graphics (www.virgingraphic.com) Local: 2010/9803 ISBN: 977-5023-12-2 Acknowledgements DIRECTOR AND Heba Handoussa LEAD AUTHOR AUTHORS Chapter One Heba Handoussa Chapter Two Ashraf el Araby, Hoda el Nemr, Zeinat Tobala Chapter Three Ghada Barsoum, Mohamed Ramadan, Safaa el Kogali Chapter Four Heba Nassar, Ghada Barsoum, Fadia