Evolution Onitoring Rogramme 2006-08

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Get Involved the Work of the Northern Ireland Assembly

Get Involved The work of the Northern Ireland Assembly Pól Callaghan MLA, Tom Elliott MLA, Gregory Campbell MP MLA and Martina Anderson MLA answer questions on local issues at Magee. Contents We welcome your feedback This first edition of the community We welcome your feedback on the newsletter features our recent Community Outreach programme conference at Magee and a number and on this newsletter. Please let of events in Parliament Buildings. us know what you think by emailing It is a snapshot of the Community [email protected] or by Outreach Programme in the Assembly. calling 028 9052 1785 028 9052 1785 Get Involved [email protected] Get Involved The work of the Northern Ireland Assembly Speaker’s overwhelmingly positive. I was deeply impressed by Introduction how passionately those who attended articulated Representative democracy the interests of their own through civic participation causes and communities. I have spoken to many As Speaker, I have always individuals and I am been very clear that greatly encouraged genuine engagement constituency. The event that they intend to get with the community is at Magee was the first more involved with the essential to the success time we had tried such Assembly as a result. of the Assembly as an a specific approach with effective democratic MLAs giving support and The Community Outreach institution. We know advice to community unit is available to that the decisions and groups including on how support, advise and liaise legislation passed in the to get involved with the with the community and Assembly are best when process of developing voluntary sector. -

28 May 2015 Chairman

28 May 2015 Chairman: Alderman A G Ewart Vice-Chairman: Alderman W J Dillon MBE Alderman: S Martin Councillors: J Baird, B Bloomfield MBE, S Carson, A P Ewing, J Gallen, A Givan, H Legge, U Mackin, T Mitchell, Jenny Palmer, S Skillen and M H Tolerton Ex Officio The Right Worshipful The Mayor, Councillor R T Beckett Deputy Mayor, Councillor A Redpath The Monthly Meeting of the Development Committee will be held in the Chestnut Room, Island Civic Centre, The Island, Lisburn, on Wednesday, 3 June 2015 at 7.00 pm for the transaction of business on the undernoted Agenda. Tea/Coffee available in Members Suite following the meeting. You are requested to attend. DR THERESA DONALDSON Chief Executive Lisburn & Castlereagh City Council Agenda 1 Apologies 2 Declarations of Interest 3 Minutes – Meeting of the Development Committee held on 13 May 2015 (Copy Attached) 4 Deputation - to receive Mr Kevin Monaghan, Eastern Divisional Manager, Transport NI, in order to present to the Committee on their Spring 2015 report. Item 1 of the Director of Development and Planning’s Report refers (7.00 pm) 5 Report from Director of Development and Planning 1. Department for Regional Development Transport NI Eastern Division 1.1 Presentation by Transport NI Eastern Division – Spring Report 2. Interim Economic Development Action Plan 2015-2017 3. Evening Economy Strategy 4. 2015 Balmoral Show 5. Speciality Food Fair – Moira Demesne 6. Lisburn and Castlereagh Restaurant Week 7. Young Enterprise Northern Ireland Fundraising Dinner – Thursday 1 October 2015 8. Lisburn and Castlereagh City Business Awards 2016 9. SME Development Programme 2015/2016 10. -

Newshound: Daily Northern Ireland News Catalog - Irish News Article

Newshound: Daily Northern Ireland news catalog - Irish News article Bereaved urge Adams — reveal truth on HOME agents This article appears thanks to the Irish News. History (Allison Morris, Irish News) Subscribe to the Irish News NewsoftheIrish The children of a Co Tyrone couple murdered by loyalists have challenged Sinn Féin president Gerry Adams to call on the IRA to reveal publicly what it knows about British agents Book Reviews working in its ranks. & Book Forum Charlie Fox (63) and his wife Tess (53) were shot at their Search / Archive home in Moy, Co Tyrone, in September 1992 by the UVF. Back to 10/96 Mrs Fox was hit in the back. Her husband was shot in the Papers head. Reference Their children spoke out yesterday (Tuesday) after a Sinn Féin 'march for truth' on Sunday which called for collusion between the British state and loyalists to be exposed and at About which Mr Adams said: "Yes, the British recruited, blackmailed, tricked, intimidated and bribed individual republicans into working for them and I think it would be Contact only right to have this dimension of British strategy investigated also." Leading loyalist Laurence George Maguire was convicted in 1994 of directing the UVF gang responsible for murdering Mr and Mrs Fox. A week before the couple's deaths their son Patrick Fox was jailed for 12 years for possession of explosives. He said yesterday that while he welcomed Mr Adams's call for disclosure on British collusion with loyalists, the truth about republican agents must be revealed. "We know now that there were moves towards a ceasefire being made as far back as 1986," he said. -

Members Imprisonment Since 1979

Members Imprisonment since 1979 Parliamentary Information List Standard Note: SN/PC/04594 Last updated: 23 January 2008 Author: Reference Services Section In all cases in which Members of either House are arrested on criminal charges, the House must be informed of the cause for which they are detained from their service to parliament. It has been usual to communicate the cause of committal of a Member after his arrest; such communications are also made whenever Members are in custody in order to be tried by naval or military courts-martial, or have been committed to prison for any criminal offence by a court or magistrate. Although normally making an oral statement, the Speaker has notified the House of the arrest or imprisonment of a Member by laying a copy of a letter on the table. In the case of committals for military offences, the communication is made by royal message. Where a Member is convicted but released on bail pending an appeal, the duty of the magistrate to communicate with the Speaker does not arise. The Parliamentary Information List Series cover various topics relating to Parliament; they include Bills, Committees, Constitution, Debates, Divisions, The House of Commons, Parliament and procedure. Also available: Research papers - impartial briefings on major bills and other topics of public and parliamentary concern, available as printed documents and on the Intranet and Internet. Standard notes – less formal briefings, often produced in response to frequently asked questions, mainly accessible via the Intranet. Factsheets – the House of Commons Information Office Factsheets provide brief informative descriptions of various facets of the House of Commons. -

Complete Dissertation

VU Research Portal Convictions, Conflict and Moral Reasoning McMillan, D.J. 2019 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) McMillan, D. J. (2019). Convictions, Conflict and Moral Reasoning: The Contribution of the Concept of Convictions in Understanding Moral Reasoning in the Context of Conflict, Illustrated by a Case Study of Four Groups of Christians in Northern Ireland. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT CONVICTIONS, CONFLICT AND MORAL REASONING The Contribution of the Concept of Convictions in Understanding Moral Reasoning in the Context of Conflict, Illustrated by a Case Study of Four Groups of Christians in Northern Ireland ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor of Philosophy aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. -

Notice of Appointment of Election Agents

Electoral Office for Northern Ireland Election of Members of the Northern Ireland Assembly for the NORTH ANTRIM Constituency NOTICE OF APPOINTMENT OF ELECTION AGENTS NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that the following candidates have appointed or are deemed to have appointed the person named as election agent for the election of Members of the Northern Ireland Assembly on Thursday 2 March 2017. NAME AND ADDRESS OF NAME AND ADDRESS OF ADDRESS OF OFFICE TO WHICH CANDIDATE AGENT CLAIMS AND OTHER DOCUMENTS MAY BE SENT IF DIFFERENT FROM ADDRESS OF AGENT Jim Allister Ms Audrey Patterson 4 Byrestown Road, Kells, 157A Finvoy Road, Ballymoney, Co. Antrim, BT42 3JB BT53 7JN Mark Francis Bailey Dr Mark Francis Bailey (address in the East Antrim 22 Ransevyn Drive, Whitehead, Constituency) Carrickfergus, County Antrim, BT38 9NW Monica Digney Mr Cathal Louis Newcombe (address in the West Belfast 45A Drumavoley Road, Ballycastle, Constituency) Co Antrim, BT54 6PQ Connor Duncan Mr Christopher McCotter North & East Antrim SDLP Office, (address in the North Antrim 4 Rossdale, Ballymena, BT42 2SA 25 Mill Street, Cushendall, BT44 0RR Constituency) Paul Frew Mr John Finlay 3 Market St, Ballymoney, BT53 6EA 11 Riverside, Broughshane, 233 Ballyveely Road, Cloughmills, Co Antrim, Northern Ireland, BT44 9NW BT42 4RZ Timothy Gaston Ms Audrey Patterson 38 Henry Street, Ballymena, BT42 3AH 32 Killycowan Road, Glarryford, 157A Finvoy Road, Ballymoney, Ballymena, BT44 9HL BT53 7JN Phillip Logan Mr John Finlay 3 Market Street, Ballymoney, BT53 6EA 34 Leighinmohr Crescent, 233 -

Summary of the 27Th Plenary Session, October 2003

BRITISH-IRISH INTER- PARLIAMENTARY BODY COMHLACHT IDIR- PHARLAIMINTEACH NA BREATAINE AGUS NA hÉIREANN _________________________ TWENTY-SEVENTH PLENARY CONFERENCE 20 and 21 OCTOBER 2003 Hanbury Manor Hotel & Country Club, Ware, Hertfordshire _______________________ OFFICIAL REPORT (Final Revised Edition) (Produced by the British-Irish Parliamentary Reporting Association) Any queries should be sent to: The Editor The British-Irish Parliamentary Reporting Association Room 248 Parliament Buildings Stormont Belfast BT4 3XX Tel: 028 90521135 e-mail [email protected] IN ATTENDANCE Co-Chairmen Mr Brendan Smith TD Mr David Winnick MP Members and Associate Members Mr Harry Barnes MP Mr Séamus Kirk TD Senator Paul Bradford Senator Terry Le Sueur Mr Johnny Brady TD Dr Dai Lloyd AM Rt Hon the Lord Brooke Rt Hon Andrew Mackay MP of Sutton Mandeville CH Mr Andrew Mackinlay MP Mr Alistair Carmichael MP Dr John Marek AM Senator Paul Coughlan Mr Michael Mates MP Dr Jerry Cowley TD Rt Hon Sir Brian Mawhinney MP Mr Seymour Crawford TD Mr Kevin McNamara MP Dr Jimmy Devins TD Mr David Melding AM The Lord Dubs Senator Paschal Mooney Ms Helen Eadie MSP Mr Arthur Morgan TD Mr John Ellis TD Mr Alasdair Morrison MSP Mr Jeff Ennis MP Senator Francie O’Brien Ms Margaret Ewing MSP Mr William O’Brien MP Mr Paul Flynn MP Mr Donald J Gelling CBE MLC Ms Liz O’Donnell TD Mr Mike German AM Mr Ned O’Keeffe TD Mr Jim Glennon TD Mr Jim O’Keeffe TD The Lord Glentoran CBE DL Senator Ann Ormonde Mr Dominic Grieve MP Mr Séamus Pattison TD Mr John Griffiths AM Senator -

Double Blind

Double Blind The untold story of how British intelligence infiltrated and undermined the IRA Matthew Teague, The Atlantic, April 2006 Issue https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2006/04/double-blind/304710/ I first met the man now called Kevin Fulton in London, on Platform 13 at Victoria Station. We almost missed each other in the crowd; he didn’t look at all like a terrorist. He stood with his feet together, a short and round man with a kind face, fair hair, and blue eyes. He might have been an Irish grammar-school teacher, not an IRA bomber or a British spy in hiding. Both of which he was. Fulton had agreed to meet only after an exchange of messages through an intermediary. Now, as we talked on the platform, he paced back and forth, scanning the faces of passersby. He checked the time, then checked it again. He spoke in an almost impenetrable brogue, and each time I leaned in to understand him, he leaned back, suspicious. He fidgeted with several mobile phones, one devoted to each of his lives. “I’m just cautious,” he said. He lives in London now, but his wife remains in Northern Ireland. He rarely goes out, for fear of bumping into the wrong person, and so leads a life of utter isolation, a forty-five-year-old man with a lot on his mind. During the next few months, Fulton and I met several times on Platform 13. Over time his jitters settled, his speech loosened, and his past tumbled out: his rise and fall in the Irish Republican Army, his deeds and misdeeds, his loyalties and betrayals. -

A Democratic Design? the Political Style of the Northern Ireland Assembly

A Democratic Design? The political style of the Northern Ireland Assembly Rick Wilford Robin Wilson May 2001 FOREWORD....................................................................................................3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................4 Background.........................................................................................................................................7 Representing the People.....................................................................................................................9 Table 1 Parties Elected to the Assembly ........................................................................................10 Public communication......................................................................................................................15 Table 2 Written and Oral Questions 7 February 2000-12 March 2001*........................................17 Assembly committees .......................................................................................................................20 Table 3 Statutory Committee Meetings..........................................................................................21 Table 4 Standing Committee Meetings ..........................................................................................22 Access to information.......................................................................................................................26 Table 5 Assembly Staffing -

THE APPARATUS of IMPUNITY? Human Rights Violations and the Northern Ireland Conflict: a Narrative of Official Limitations on Post-Agreement Investigative Mechanisms

THE APPARATUS OF IMPUNITY? Human rights violations and the Northern Ireland conflict: a narrative of official limitations on post-Agreement investigative mechanisms Committee on the Administration of Justice January 2015 The Apparatus of Impunity? Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) © Committee on the Administration of Justice January 2015 The material may be reproduced, free of charge, in any format or medium without specific permission, provided the reproduction is not for financial or material gain.The material must be reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. If the material is to be republished or issued to others, acknowledgement must be given to its source, copyright status, and date of publication. This publication is available on our website. CAJ Committee on the Administration of Justice 2nd Floor, Sturgen Building 9-15 Queen Street Belfast BT1 6EA Tel: 028 9031 6000 Fax: 028 9031 4583 [email protected] www.caj.org.uk ISBN 978 1 873285 94 7 The Apparatus of Impunity? Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) THE APPARATUS OF IMPUNITY? Human rights violations and the Northern Ireland conflict: a narrative of official limitations on post-Agreement investigative mechanisms Committee on the Administration of Justice January 2015 The Apparatus of Impunity? Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) Recent comments from key Council of Europe and UN human rights bodies in relation to existing mechanisms investigating the conflict in Northern Ireland: The absence of any plausible explanation for the failure to collect key evidence at the time when this was possible, and for attempts to even obstruct this process, should be treated with particular vigilance. -

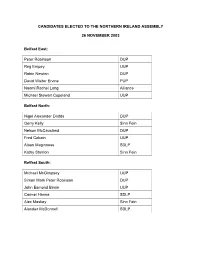

Peter Robinson DUP Reg Empey UUP Robin Newton DUP David Walter Ervine PUP Naomi Rachel Long Alliance Michael Stewart Copeland UUP

CANDIDATES ELECTED TO THE NORTHERN IRELAND ASSEMBLY 26 NOVEMBER 2003 Belfast East: Peter Robinson DUP Reg Empey UUP Robin Newton DUP David Walter Ervine PUP Naomi Rachel Long Alliance Michael Stewart Copeland UUP Belfast North: Nigel Alexander Dodds DUP Gerry Kelly Sinn Fein Nelson McCausland DUP Fred Cobain UUP Alban Maginness SDLP Kathy Stanton Sinn Fein Belfast South: Michael McGimpsey UUP Simon Mark Peter Robinson DUP John Esmond Birnie UUP Carmel Hanna SDLP Alex Maskey Sinn Fein Alasdair McDonnell SDLP Belfast West: Gerry Adams Sinn Fein Alex Atwood SDLP Bairbre de Brún Sinn Fein Fra McCann Sinn Fein Michael Ferguson Sinn Fein Diane Dodds DUP East Antrim: Roy Beggs UUP Sammy Wilson DUP Ken Robinson UUP Sean Neeson Alliance David William Hilditch DUP Thomas George Dawson DUP East Londonderry: Gregory Campbell DUP David McClarty UUP Francis Brolly Sinn Fein George Robinson DUP Norman Hillis UUP John Dallat SDLP Fermanagh and South Tyrone: Thomas Beatty (Tom) Elliott UUP Arlene Isobel Foster DUP* Tommy Gallagher SDLP Michelle Gildernew Sinn Fein Maurice Morrow DUP Hugh Thomas O’Reilly Sinn Fein * Elected as UUP candidate, became a member of the DUP with effect from 15 January 2004 Foyle: John Mark Durkan SDLP William Hay DUP Mitchel McLaughlin Sinn Fein Mary Bradley SDLP Pat Ramsey SDLP Mary Nelis Sinn Fein Lagan Valley: Jeffrey Mark Donaldson DUP* Edwin Cecil Poots DUP Billy Bell UUP Seamus Anthony Close Alliance Patricia Lewsley SDLP Norah Jeanette Beare DUP* * Elected as UUP candidate, became a member of the DUP with effect from -

Shooting Similar to Donaldson Killing in 2006 - National News, Frontpage - Independent.Ie

Shooting similar to Donaldson killing in 2006 - National News, Frontpage - Independent.ie ● Skip Skip Links Thursday,Work February 14 2008 to navigation with ● Skip us? 8° Dublin Hi 8°C / Lo 3°C Go to primary content ● Skip National News to secondary content Headlines l How I learned to flirt ● Skip Night on the town to tertiary content with dating coach ● Skip see Relationships to footer Navigation ● News ● Business ❍ Breaking News ❍ National News ● Sport ❍ World News ● Entertainment ❍ Today's Paper ● Health ❍ Regional Newspapers ● Lifestyle ❍ Opinion ● Education ❍ Farming ❍ ● Travel Weather ❍ Budget 2008 ● Jobs ● Property ● Cars ● PlaceMyAd ● More Services ● from the Irish Independent & Sunday Independent Breadcrumbs You are here: Home > National News Advertiser Links poweredShooting similar to Donaldson killing in 2006 Breaking News byBy Anita Guidera Thursday February 14 2008 Tools News National News World News Sport 10:34 Unison. The brutal killing of Andrew Burns in a remote area of Donegal is the Print Email Two second paramilitary-style murder to happen in the county in the past two sought after ieyears. Search armed robbery at Co Limerick shop 10:31Guinness sales up 6% in Ireland and Britain On April 3, 2006, high profile Sinn Fein member Denis Donaldson (56) Go was hit by four shotgun blasts at his remote cottage at Classey, five 09:44O'Rourke says Education Dept is biased miles from Glenties in west Donegal on the back road to Doochary. Related Articles against ABA 07:54British-Irish Council to meet in Dublin this ● Churchyard murder victim had Republican involvement has been linked with both murders but has been morning denied.