Revolutionary Desire: Nonsense in Language and Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ash Ra Tempel Join Inn Mp3, Flac, Wma

Ash Ra Tempel Join Inn mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Rock Album: Join Inn Country: France Released: 1991 Style: Krautrock, Prog Rock, Ambient MP3 version RAR size: 1751 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1544 mb WMA version RAR size: 1350 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 381 Other Formats: XM ADX TTA AUD APE WMA DTS Tracklist 1 Freak 'n' Roll 19:15 2 Jenseits 24:18 Companies, etc. Distributed By – MSI Manufactured By – Tecval Memories SA Phonographic Copyright (p) – Tempel Copyright (c) – Tempel Phonographic Copyright (p) – Spalax Music Copyright (c) – Spalax Music Recorded At – Dierks Studios Credits Bass – Hartmut Enke Cover – Günter Gritzner Drums, Organ, Synthesizer [Synthi A] – Klaus Schulze Engineer – Dieter Dierks Guitar – Manuel Göttsching Music By, Lyrics By [Text By] – Hartmut Enke, Klaus Schulze, Manuel Göttsching Producer [Ein Ohr Produktion Von] – Rolf-Ulrich Kaiser Voice [Stimme] – Rosi* Notes Sechsunddreißigste Ohr - Platte. Aufgenommen im Dezember 1972 während der Produktion der LP "Tarot" im Studio Dierks. Copyright information: On booklet rear: RERELEASE P + C 1991 TEMPEL, SPALAX MUSIC, PARIS, FRANCE Disc print is blue ink on this version with MSI circled logo (no Spalax) MANUFACTURED IN SWITZERLAND BY TECVAL Catalogue number variations are: 14246 on tray inlay and disc, EL 14246 on spines (EL is rotated). Released originally in 1973 on Ohr Records (OMM 556032). Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout: SPA10218-14246 Rights Society: SACEM SACD SDRM SGDL Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year OMM 556.032, Ash Ra OMM 556.032, Join Inn (LP, Album) Ohr, Ohr Germany 1973 OMM 556032 Tempel OMM 556032 Ash Ra Join Inn (CD, Album, Purple CLP 1258-2 CLP 1258-2 US 2002 Tempel RE) Pyramid OMM 556032, Ash Ra Join Inn (LP, Album, OMM 556032, Ohr , Ohr Europe 2017 OMM 556.032 Tempel RE, Unofficial) OMM 556.032 Ash Ra Join Inn (LP, Album, OMM 556032 Ohr OMM 556032 Germany 2011 Tempel Ltd, RE, Unofficial) Klaus Klaus Schulze, Ash Pld. -

Zoomagazine Interview 2

MANUEL GÖTTSCHING Im Wachsfigurenkabinett von Tokio hat man ihn zwischen Abraham Lincoln und Marilyn Monroe aufgestellt: Manuel Göttsching, geboren 1952 in West-Berlin, spielte Anfang der 70er Jahre in der legendären Krautrock-Formation Ash Ra Tempel, zehn Jahre später schrieb er mit seinem einstündigen Synthesizer-Epos "E2-E4" Musikgeschichte. Im New Yorker Studio 54 spielte man das Stück gerne zum Warmwerden, um die Ecke in der Paradise Garage krönte es die Sets des DJ- Pioniers Larry Levan. 1989 diente das Stück als Basis des millionenfach verkauften Ibiza-Gassenhauers "Sueno Latino", seitdem wurde "E2-E4" unzählige Male gesamplet, gecovert und imitiert. Während zum 25. Geburtstag des Stücks neue Remixe auf den Markt kommen, sitzt Manuel Göttsching noch immer im tiefsten Berlin-Schöneberg, um die Ecke eines Etablissements namens "Big Sexyland", und arbeitet an Musik, die das Zeitempfinden ihrer Hörer nachhaltig außer Kraft setzt. Ein Gespräch über Timothy Leary, reiche Japaner, Klaus Nomi und vorsintflutliche Lochkarten-Synthesizer. Herr Göttsching, Sie haben 1981 mit "E2-E4" ein Stück aufgenommen, das als wegweisend für die Entwicklung der elektronischen Tanzmusik gilt. Was war das für ein Tag, an dem das Stück entstand? Hmm. Also das Datum weiß ich ja noch, das war der 12. Dezember 1981, aber sonst... Haben Sie nie versucht, zu rekonstruieren, was an dem Tag möglicherweise besonders war, ob es eine außergewöhnliche Sternenkonstellation gab oder so etwas? Nein. Vielleicht klingt es komisch, aber ich denke, "E2-E4" ist einfach so gut geworden, weil ich den Kopf total frei hatte. Ich habe gar nicht daran gedacht, dass ich da jetzt was besonders Tolles machen muss, was ich veröffentlichen kann. -

Emissaries Press Quotes

WHAT THE PRESS HAS SAID ABOUT: RADIO MASSACRE INTERNATIONAL EMISSARIES CUNEIFORM 2004 Lineup: Steve Dinsdale (lamm memorymoog, mellotron, maq 16/3 sequencer, percussion, great british spring, devices) Gary Houghton (electric guitar, acoustic guitar, jam-man, theremin, devices) Duncan Goddard (yamaha cs50 & cs30, P3 sequencer, maq 16/3 sequencer, roland sh3a, repeater, moog source, bass, korg vc-10 vocoder & es-1 sampler, devices) “Each of the two CDs in the double disc set Emissaries…presents a distinctive facet of this interesting trio… Disc 1: “The Emissaries Suite”…is essentially a studio album. While the music on this disc feels more arranged and composed than the group's live concert albums, RMI's freewheeling style is ever present. The pieces unfold, expand and recede as if in a rehearsed jam session rather than a clinical/critical studio project. The keystone supporting this music is Duncan Goddard's sequencer patterns. Multiple sets of cycling synthesizer tones dance, skip and echo through minor key scales, running full-tilt like a runaway train. …Disc 2: “Ancillary Blooms”…is a live album… two one hour sets were edited down so as to fit on this CD, and flow along a subtle spatial arc suitable for late-night listening. Within this setting the sonic inventions are more discovered than composed as the trio tends to explore areas of texture and mood. The ensuing musical themes grew out of an improvisational interaction that could not have been planned, nor repeated. When it comes to playing music under these conditions, RMI call on their instincts. …they produce complex atmospheric realizations. -

![Troupiers [BANDES À PART] E Fut Une Parenthèse En- Tout L’Été, «Libération» Baguenaude Dans Des Groupes Chantée Au Faîte De La Mu- À La Marge](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0994/troupiers-bandes-%C3%A0-part-e-fut-une-parenth%C3%A8se-en-tout-l-%C3%A9t%C3%A9-%C2%ABlib%C3%A9ration%C2%BB-baguenaude-dans-des-groupes-chant%C3%A9e-au-fa%C3%AEte-de-la-mu-%C3%A0-la-marge-1640994.webp)

Troupiers [BANDES À PART] E Fut Une Parenthèse En- Tout L’Été, «Libération» Baguenaude Dans Des Groupes Chantée Au Faîte De La Mu- À La Marge

Aujourd’hui : Dans la chambre de Nicolas Le Riche, des moules farcies à Sète, Doc Gynéco sur le périph… Le bassiste allemand d’Ash Ra Tempel, Hartmut Enke (à g.), au côté de l’Américain Timothy Leary. Eté 1972. MARCEL FUGERE.2011 MG.ART Cosmiques troupiers [BANDES À PART] e fut une parenthèse en- Tout l’été, «Libération» baguenaude dans des groupes chantée au faîte de la mu- à la marge. Aujourd’hui, le compagnonnage sous acide entre le chantre sique pop, une poignée de C demi-dieux qui passaient américain du LSD, Timothy Leary,et des musiciens allemands réunis par leur temps torse nu, ou plutôt de «messagers cosmiques» (puis- une vision. C’était en Suisse, à l’été 1972. Par GRÉGORY SCHNEIDER qu’ils se considéraient comme tels) LIBÉRATION Lundi 18 juillet 2011 www.liberation.fr II • BANDES À PART La bande du projet et disque Seven Up au complet dans la ferme de Mindy, près de Berne, en 1972. PHOTO MARCEL FUGERE. 2011 MG.ART réunis par une sorte de vision. Et dre puisqu’il suppose l’annihilation de plus en plus lointain au fil du temps prôner la libération de la conscience par les circonstances: les subtilités de la lé- complète de l’ego. Il y avait aussi le dé- qui passe et des écoutes. l’absorption d’acide et envoyer la jeu- gislation helvète, un appel d’air à en- sir de «consolider le monde avec un mé- Cette affaire s’est tramée deux ans plus nesse dans des hôpitaux psychiatri- gloutir une planète et l’ambition floue lange de héros rock’n’roll et d’illumina- tôt, dans la prison de Luis Obispo (Cali- ques: le président Richard Nixon parle d’inventer le son du paradis mais aussi, tions», comme l’a synthétisé le fornie), où Leary, 51 ans à l’époque, alors de Leary comme de «l’homme le qui sait, le monde qui va avec. -

Krautrock and the West German Counterculture

“Macht das Ohr auf” Krautrock and the West German Counterculture Ryan Iseppi A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH HONORS DEPARTMENT OF GERMANIC LANGUAGES & LITERATURES UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN April 17, 2012 Advised by Professor Vanessa Agnew 2 Contents I. Introduction 5 Electric Junk: Krautrock’s Identity Crisis II. Chapter 1 23 Future Days: Krautrock Roots and Synthesis III. Chapter 2 33 The Collaborative Ethos and the Spirit of ‘68 IV: Chapter 3 47 Macht kaputt, was euch kaputt macht: Krautrock in Opposition V: Chapter 4 61 Ethnological Forgeries and Agit-Rock VI: Chapter 5 73 The Man-Machines: Krautrock and Electronic Music VII: Conclusion 85 Ultima Thule: Krautrock and the Modern World VIII: Bibliography 95 IX: Discography 103 3 4 I. Introduction Electric Junk: Krautrock’s Identity Crisis If there is any musical subculture to which this modern age of online music consumption has been particularly kind, it is certainly the obscure, groundbreaking, and oft misunderstood German pop music phenomenon known as “krautrock”. That krautrock’s appeal to new generations of musicians and fans both in Germany and abroad continues to grow with each passing year is a testament to the implicitly iconoclastic nature of the style; krautrock still sounds odd, eccentric, and even confrontational approximately twenty-five years after the movement is generally considered to have ended.1 In fact, it is difficult nowadays to even page through a recent issue of major periodicals like Rolling Stone or Spin without chancing upon some kind of passing reference to the genre. -

First-Ever Vinyl Reissue of Chronolyse, the Moog and 70S Analogue

Bio information: RICHARD PINHAS Title: CHRONOLYSE (Cuneiform Rune 30) Format: CD / LP / DIGITAL Cuneiform promotion dept: (301) 589-8894 / fax (301) 589-1819 email: joyce [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (Press & world radio); radio [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (North American & world radio) www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: ROCK / ELECTRONIC MUSIC / EXPERIMENTAL First-Ever Vinyl Reissue of Chronolyse, The Moog and 70s Analogue Electronics Masterwork Created by Richard Pinhas, France’s Legendary Electronique Guerilla, in Tribute to Frank Herbert’s Sci-Fi Classic, Dune 2015 marks the 50th Anniversary of Dune Cuneiform Records is proud to announce the first-ever vinyl reissue of Chronolyse, the masterwork of 1970s analogue electronics that French electronic musician and guitarist Richard Pinhas created in tribute to Frank Herbert’s sci-fi classic, Dune. This special reissue, pressed on 180 gram white vinyl and featuring the original album artwork, celebrates Chronolyse’s conception nearly 40 years ago as well as the 50th anniversary of Dune, the first volume of which was published in 1965. Back in 1974, Pinhas received his PhD in Philosophy from the Sorbonne, where he had studied with French philosopher Gilles Deleuze and written his dissertation, “Science-Fiction, Inconscient et Autres Machins”, on the intersections of time, time manipulation, science fiction and analogue electronic music. That same year he founded Heldon. a band that fused his searing guitar with experimental electronics to revolutionize rock music in France. By 1976 Heldon had released several albums on Pinhas’ Disjuncta label (one of France’s first independent labels), and began working on a new album, Interface. Simultaneous with the Interface sessions, Pinhas immersed himself in a highly personal and heartfelt solo project. -

Ambient Music

Înv ăţământ, Cercetare, Creaţie (Education, Research, Creation) Volume I AMBIENT MUSIC Author: Assistant Lecturer Phd. Iliana VELESCU Ovidius University Constanta Faculty of Arts Abstract: Artistic exploration period of the early 20th century draws two new directions in art history called Dadaism and Futurism. Along with the painters and writers who begin to manifest in these artistic directions, is distinguished composers whose works are focused on producing electronic, electric and acoustic sounds. Music gets a strong minimalist and concrete experimental type, evolving in different genres including the ambient music. Keywords: ambient music, minimalism, experimental music Ambient music is a derivative genre of electronic music known as background music developed from traditional musical structures, and generally focuses on timbre sound and creating a specific sound field. The origins of this music are found in the early 20th century, shortly before and after the First World War. This period of exploration and rejection of what was classical and traditionally gave birth of two artistic currents called in art history, Dadaism and Futurism. Along with painters and writers manifested in these artistic directions were distinguished experimental musician such as Francesco Balilla Pratella, Kurt Schwitters and Erwin Schulhoff. This trend has had a notable influence in Erik Satie works which consider this music as „music of furniture” (Musique d'ameublement) and proper to create a suitable background during dinner rather than serving as the focus of attention1. The experimental trend has evolved at the same time with the „music that surrounds us” which start to delimitated the cosmic sounds, nature sounds, and sound objects - composers being attracted by sound exploring in microstructure and macrostructure level through the emergence and improvement of acoustic laboratories or electronic music studios as well as Iannis Xenakis, Pierre Boulez, Karl Stockausen. -

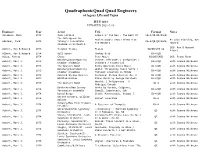

Quadraphonicquad Multichannel Engineers of All Surround Releases

QuadraphonicQuad Multichannel Engineers of all surround releases JULY 2021 UPDATED 2021-7-16 Type Engineer Year Artist Title Format Notes 5.1 Production Live… Greetins From The Flow MCH Dishwalla Services, State MCH Abraham, Josh 2003 Staind 14 Shades of Grey DVD-A with Ryan Williams Quad Abramson, Mark 1973 Judy Collins Colors of the Day - The Best Of CD-4/Q8/QR/SACD MCH Acquah, Ebby Depeche Mode 101 Live SACD The Outrageous Dr. Stolen Goods: Gems Lifted from P: Alan Blaikley, Ken Quad Adelman, Jack 1972 Teleny's Incredible CD-4/Q8/QR/SACD the Masters Howard Plugged-In Orchestra MCH Ahern, Brian 2003 Emmylou Harris Producer’s Cut DVD-A MCH Ainlay, Chuck David Alan David Alan DVD-A MCH Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Dire Straits Brothers In Arms DVD-A DualDisc/SACD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Dire Straits Alchemy Live DVD/BD-V MCH Ainlay, Chuck Everclear So Much for the Afterglow DVD-A MCH Ainlay, Chuck George Strait One Step at a Time DTS CD MCH Ainlay, Chuck George Strait Honkytonkville DVD-A/SACD MCH Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Sailing To Philadelphia DVD-A DualDisc MCH Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Shangri La DVD-A DualDisc/SACD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Mavericks, The Trampoline DTS CD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Olivia Newton John Back With a Heart DTS CD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Pacific Coast Highway Pacific Coast Highway DTS CD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Peter Frampton Frampton Comes Alive! DVD-A/SACD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Trisha Yearwood Where Your Road Leads DTS CD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Vince Gill High Lonesome Sound DTS CD/DVD-A/SACD QSS: Ron & Howard Quad Albert, Ron & Howard 1975 -

Krautrock: the Obscure Genre That Changed the Sound of Rock by Zane Van Dusen

Krautrock: The Obscure Genre That Changed the Sound of Rock By Zane Van Dusen In 1968, a new genre of music appeared in Germany. This music, which had elements of 1960’s rock and experimental music, received the patronizing nickname ‘Krautrock,’ from the British press.1 Due to the relatively small size of this musical movement and the somewhat offensive moniker, Krautrock was all but forgotten in the 1980s and 1990s. Music critics and historians placed the bands from this movement (like Faust, Neu!, Kraftwerk, Tangerine Dream) in broad genres like “progressive rock” and “psychedelic rock,” and the “press would [not] give such bands more than a jokey note in the 'Where are they now' columns.”2 Then, in 1995, Julian Cope released a book titled Krautrocksampler. The book outlined a history of the Krautrock genre, including reviews of important bands, albums and concerts, and concluded with a list of Cope’s top 50 Krautrock albums. Cope’s book received much praise and started a huge revival of interest within the underground music scene, in addition to introducing “the word 'Krautrock' in a positive, pouting glam rock way.”3 Since the release of Krautrocksampler, Krautrock has become a buzzword in experimental, indie and electronic music publications, like Wire, Pitchfork, and Electronic Musician, and its wide ranging influence is often noted. Although Krautrock was a small and localized movement, this unique genre had a profound impact on modern music, and is just starting to get recognition for it. History and Cultural Background In the 1950s and 1960s, British and American rock music had taken the music world by storm. -

Manuel Gottsching and Ash Ra Tempel Kraftwerk

296 THE AMBIENT CENTURY AMBIENCE IN THE ROCK ERA 297 minimalism of Like The comDll1ll1g his sweetly toned guitar style with mellow keyboard patten> of AJomenti FeUd (Virgin Venture 1987). Brian Eno sponsored sounds. New Age Of Earth (1977) danced along on a rush some of the tonal on the Japanese collection, Pink, Blue And Amher sounds, lapping on the shores ofFleetwood Mac blues one moment, off 1996). for a fresh overview ofeverything Roedelius has to ofIer, try into the cosmic ether the next. Here texture was Gottsching going /~ !1WIypl/n (All Saints out of his way to create an interplanetary sound of the future. Blackouts (I was less but his guitar glowed as usual. Correlations (1979) and Bell Alliance (1980) had their moments but Gottsching was increasingly at odds with the some of the drum-machine tracks sounding positively awk MANUEL GOTTSCHING AND ASH RA TEMPEL ward. Sensing his music needed more concentration, he took time off and during the last month of 1981 recorded the astonishing E2-E4 One ofthe most mellifluously gifted guitarists to come out ofthe German rock a wonderfully dancey rhythm track with space for liquid sounds, scene of the 1970s was Manuel Gottsching. His fusion of bass grooves, hesitant nervy keyboard motifs and the silken provisation with electronic treatments made his first group, Ash Ra notes of old. At nearly an hour long it a space all ofits own, thus one of the m<;>st exciting Gennan bands oftheir era. the mid-1970s he was a becoming one ofthe most-sampled records ofthe House ofthe 19805 solo inventor, allying his fender and Gibson streams with effects to the and 19905 a veritable soundtrack for the E generation. -

Beyond the Infinite Compiled in 2019

E ST 2 01 2 The Malcolm Garrett Collection Playlist #7 Beyond the Infinite Compiled in 2019 Pop has had a fascination with other worlds and what lies Stylophone, and neatly straddled the release of Stanley Kubrick’s beyond the stars ever since the beginning of man’s exploration epic film 2001 – A Space Oddysey (1968) and the moment Neil of space. Although there were no doubt many precedents, Armstrong stepped onto the surface of the moon for the first time, musicians began to respond in earnest after a futuristic for all mankind (July 1969). It wasn’t long before access to off-the- recording by The Tornados, celebrating the 1962 launch of shelf synthesisers became readily available. As the ’70s dawned, Telstar, the world’s first operational communications satellite, and adventurous rock bands looked to expand their sonic horizons, rocketted to the top of the charts. In a weird twist of logic manufacturers such as Moog, ARP and EMS (with its ever-popular though this is my final track. VCS3), all released affordable and portable electronic synthesisers, thus liberating electronics from the experimental, laboratory Despite it being an obvious milestone, and chronoligally asks to environment, and introduced previously unheard sounds into the be the opener, Telstar somehow felt out of place at the start of this hands of rock musicians and the ears of their audiences. sequence of tracks, which are mainly from the second half of the ’60s when the Space Race was at its peak. For a combination of With notable exceptions, such as Brian Eno of course, it seemed pop sensibility and clear reference to outer space, enhanced by a to me that it was primarily musicians in Berlin, Cologne and knowing lyric that is dripping with psychedelic awareness, I initially Düsseldorf* who pushed the boundaries. -

Quadraphonicquad Quad Engineers of Legacy Lps and Tapes

QuadraphonicQuad Quad Engineers of legacy LPs and Tapes JULY 2021 UPDATED 2021-7-16 Engineer Year Artist Title Format Notes Abramson, Mark 1973 Judy Collins Colors of the Day - The Best Of CD-4/Q8/QR/SACD The Outrageous Dr. Stolen Goods: Gems Lifted from P: Alan Blaikley, Ken Adelman, Jack 1972 Teleny's Incredible CD-4/Q8/QR/SACD the Masters Howard Plugged-In Orchestra QSS: Ron & Howard Albert, Ron & Howard 1975 Stephen Stills Stills SQ/Q8/DTS CD Albert Albert, Ron & Howard 1974 Bill Wyman Monkey Grip CD-4/Q8 Allen, Murray 1974 Chase Pure Music SQ/Q8/SACD QSS: Frank Rand Weisberg/Contemporary Varese: Offrandes / Intégrales / Aubort, Marc J. 1973 CD-4/QR with Joanna Nickrenz Chamber Ensemble Octandre / Ecuatorial Aubort, Marc J. 1973 The Western Wind Early American Vocal Music CD-4/QR with Joanna Nickrenz Weisberg/Contemporary Weill: Threepenny Opera Suite / Aubort, Marc J. 1973 CD-4/QR with Joanna Nickrenz Chamber Ensemble Milhaud: Creation du Monde Aubort, Marc J. 1973 Concord String Quartet Rochberg: String Quartet No. 3 CD-4/QR with Joanna Nickrenz Aubort, Marc J. 1973 William Bolcom Piano Music by George Gershwin CD-4/QR with Joanna Nickrenz Vecchi: L'Amfiparnaso - A Aubort, Marc J. 1973 The Western Wind CD-4 with Joanna Nickrenz Madrigal Comedy DesRoches/New Jersey Works by Varese, Colgrass, Aubort, Marc J. 1974 CD-4/QR with Joanna Nickrenz Percussion Ensemble Cowell, Saperstein, Oak Aubort, Marc J. 1974 David Burge Crumb: Makrocosmos, Volume I CD-4/QR with Joanna Nickrenz Gerard Schwarz, William Aubort, Marc J. 1974 Cornet Favorites CD-4 with Joanna Nickrenz Bolcom Schwarz/New York Trumpet Aubort, Marc J.