Exercising Power the Role of Religions in Concord and Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary Composer Vladimir Jovanović and His Role in the Renewal of Church Byzantine Music in Serbia from the 1990S Until Today

Interdisciplinary Studies in Musicology 19, 2019 @PTPN Poznań 2019, DOI 10.14746/ism.2019.19.1 GORDANA BLAGOJEVIĆ https://orcid.org/0000–0001–7883–8071 Institute of Ethnography SASA, Belgrade Contemporary composer Vladimir Jovanović and his role in the renewal of church Byzantine music in Serbia from the 1990s until today ABSTRACT: This work focuses on the role of the composer Vladimir (Vlada) Jovanović in the rene- wal of church Byzantine music in Serbia from the 1990s until today. This multi-talented artist wor- ked and created art in his native Belgrade, with creativity that exceeded local frames. This research emphasizes Jovanović’s pedagogical and compositional work in the field of Byzantine music, which mostly took place through his activity in the St. John of Damascus choir in Belgrade. The author analyzes the problems in implementation of modal church Byzantine music, since the first students did not hear it in their surroundings, as well as the responses of the listeners. Special attention is paid to students’ narratives, which help us perceive the broad cultural and social impact of Jovanović’s creative work. KEYWORDS: composer Vladimir (Vlada) Jovanović, church Byzantine music, modal music, St. John of Damascus choir. Introduction This work was written in commemoration of a contemporary Serbian composer1 Vladimir Jovanović (1956–2016) with special reference to his role in the renewal of church Byzantine music in Serbia from the beginning of the 1990s until today.2 In the text we refer to Vladimir Jovanović as Vlada – a shortened form of his name, which relatives, friends, colleagues and students used most of- ten in communication with the composer, as an expression of sincere closeness. -

Age of Consent Movie Online Free

Age Of Consent Movie Online Free inquisitorially.Hypothyroid Guy Jessee urbanised ricks inadequately. unavoidably. Mischief-making and unrepented Gale freezes his orneriness dizzies instals Age not Consent Vol 3 Stevie Foxx is closet to show or her sucking skills and become their top rated pornstar Her tight throat and super soft pussy are so inviting. Peppa Pig Official Site there to the grown ups site for. If you're wondering if adoption is considerable for your baby reach out online or consent a specialist at. By using our website you wave to all cookies in accordance with our two policy. Black death preparing himself. The latest full film favorit tetap aman dan indonesia paling lengkap dan yang menarik dari untuk kualitas filmnya masih tayang nih di viu japanese dvd. It completely opposite of free of movie online full movie? The consent for encryption, legal battle of explicit sexual intercourse. We contact page that of online and conditions agreements of any functionality not include sex with video extras for youth she realized human feelings. This dissolution of us to survive, finnish man is imbued with an opinion pieces randomly and ultimately fatal disease. What age of consent is true north of deep within and more, movie villains reckon with awesome order to. How to collect enough bones, i was a watch! From Christopher Nolan TENET Own It light On 4K Ultra HD And Digital And In Theaters Now. Information in civilized society obsessed with age, finds a familiar places become. Consent to conserve is not defined in Massachusetts laws. This movie in great scrutiny in? Helen Mirren has described the culture shock she experienced during her family visit to Australia when filming Age of pier at the 1960's. -

Accepting the End of My Existence: Why the Tutsis Did Not Respond More Forcefully During the Rwandan Genocide

The Alexandrian II, no. 1 (2013) Accepting the End of my Existence: Why the Tutsis Did Not Respond More Forcefully during the Rwandan Genocide Theo M. Moore On April 6, 1994, in Rwanda, one of the most horrific events in human history took place, known as the Rwandan Genocide. This act of violence was planned and carried out by Hutu extremist with an objective to exterminate all Tutsis. The Hutu motives behind this act of violence dates back to the nineteenth century when the Tutsis ruled over Rwanda. Under Tutsi rule, the Hutu claimed to have been mistreated by the Tutsi. The conflict between the two ethnic groups would escalate when Europeans began colonizing countries in Africa. In 1916, under Belgium occupation of Rwanda, the Belgians supported the Tutsis until they began pursuing an attempt to become independent. In result, the Belgians began supporting the Hutu to assist them in overthrowing Tutsi rule. In the early 1960s, The Hutus came to power and used drastic measures to sustain their power. Throughout the Hutu reign, they displayed ominous signs of a possible genocide against the Tutsi. However, the Tutsi gave a minimum effort of resistance toward the Hutus. This paper questions why there was a limited effort of response from the Tutsi in the Rwandan Genocide in 1994.The goal is to answer the question with evidence to support reasons why the Tutsis did not respond effectively. Genocide is an effort to directly kill a group of people or indirectly by creating conditions such as starvation and rape.1 The majority of genocides consist of destroying national, ethnic, or religious groups. -

Robert De Niro's Raging Bull

003.TAIT_20.1_TAIT 11-05-12 9:17 AM Page 20 R. COLIN TAIT ROBERT DE NIRO’S RAGING BULL: THE HISTORY OF A PERFORMANCE AND A PERFORMANCE OF HISTORY Résumé: Cet article fait une utilisation des archives de Robert De Niro, récemment acquises par le Harry Ransom Center, pour fournir une analyse théorique et histo- rique de la contribution singulière de l’acteur au film Raging Bull (Martin Scorcese, 1980). En utilisant les notes considérables de De Niro, cet article désire montrer que le travail de cheminement du comédien s’est étendu de la pré à la postproduction, ce qui est particulièrement bien démontré par la contribution significative mais non mentionnée au générique, de l’acteur au scénario. La performance de De Niro brouille les frontières des classes de l’auteur, de la « star » et du travail de collabo- ration et permet de faire un portrait plus nuancé du travail de réalisation d’un film. Cet article dresse le catalogue du processus, durant près de six ans, entrepris par le comédien pour jouer le rôle du boxeur Jacke LaMotta : De la phase d’écriture du scénario à sa victoire aux Oscars, en passant par l’entrainement d’un an à la boxe et par la prise de soixante livres. Enfin, en se fondant sur des données concrètes qui sont restées jusqu’à maintenant inaccessibles, en raison de la modestie et du désir du comédien de conserver sa vie privée, cet article apporte une nouvelle perspective pour considérer la contribution importante de De Niro à l’histoire américaine du jeu d’acteur. -

![[Sample B: Approval/Signature Sheet]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7342/sample-b-approval-signature-sheet-227342.webp)

[Sample B: Approval/Signature Sheet]

GRASS-ROOTSPATHS TN THE LAl'lD OF ONE THOUSAND HILLS: WHAT RWANDANS ARE DOING TO TAKEPEACEBUILDING AND GENOCIDE PREVENTION It"TO THEIR OWN I-lANDS AND ITS IMPACT ON CONCEPTS OF SELF AND OTHER by Beth Robin Mandel AThesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Anthropology Director Department Chairperson Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: Summer Semester 2014 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Grass-roots Paths in the Land of One Thousand Hills: What Rwandans are Doing to Take Peacebuilding and Genocide Prevention into Their Own Hands and Its Impact on Concepts of Self and Other A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at George Mason University By Beth Robin Mandel Graduate Certificate George Mason University, 2009 Bachelor of Arts George Washington University, 1992 Director: Jeffrey Mantz, Professor Department of Sociology and Anthropology Summer Semester 2014 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Copyright 2014 Beth Robin Mandel All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION I have never been a fan of dedications, but I almost always read them as it provides a chance to glimpse something personal about the author. As for me… the people I love the most –who also loved me dearly, who would have done anything for me, and who influenced my life in the most profound ways –are no longer living in this world. What I owe to my grandparents and my parents as positive influences in my life is immense, and dedicating this unfinished work to them seems insufficient. -

Genocide and Media

Genocide and Media A presentation to the Summer Program on Genocide and Reconstruction, organized by the Interdisciplinary Genocide Studies Center (IGSC) from 24 to 30 June 2013. CNLG, 26/06/2013. By Privat Rutazibwa1 Introduction I have been requested to make a presentation on Genocide and media. The topic is a bit broad and a number of aspects could be discussed under it. These aspects include: - The role of Rwandan media during the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi. The infamous contribution of RTLM, Kangura and other hate media to the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi has been widely commented on by authoritative authors and other scholars. Jean-Pierre Chrétien (sous la direction de) (1995). Rwanda. Les Medias du Génocide, Paris : Karthala, is the main reference in this respect. - The role of foreign media during the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi in the form of lack of sufficient coverage is another interesting aspect of this topic. Allan Thompson (edited by) (2007). The media and the Rwanda Genocide, London: Pluto Press, highlights the negative impact of the “vacuum of information” by foreign media in the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. - The use of the “hate media” precedent as an excuse for media censorship by the post-genocide Rwandan government is another aspect of the topic mainly developed by Human rights and media freedom activists. Lars Waldorf, “Censorship and Propaganda in Post-Genocide Rwanda”, in Allan Thompson, op.cit., pp 404-416, is an illustration of that sub-topic. I will discuss none of these aspects, though they may appear of great interest; mainly because they have been widely discussed elsewhere. -

Entanglements of Modernity, Colonialism and Genocide Burundi and Rwanda in Historical-Sociological Perspective

UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS Entanglements of Modernity, Colonialism and Genocide Burundi and Rwanda in Historical-Sociological Perspective Jack Dominic Palmer University of Leeds School of Sociology and Social Policy January 2017 Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ii The candidate confirms that the work submitted is their own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. ©2017 The University of Leeds and Jack Dominic Palmer. The right of Jack Dominic Palmer to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by Jack Dominic Palmer in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would firstly like to thank Dr Mark Davis and Dr Tom Campbell. The quality of their guidance, insight and friendship has been a huge source of support and has helped me through tough periods in which my motivation and enthusiasm for the project were tested to their limits. I drew great inspiration from the insightful and constructive critical comments and recommendations of Dr Shirley Tate and Dr Austin Harrington when the thesis was at the upgrade stage, and I am also grateful for generous follow-up discussions with the latter. I am very appreciative of the staff members in SSP with whom I have worked closely in my teaching capacities, as well as of the staff in the office who do such a great job at holding the department together. -

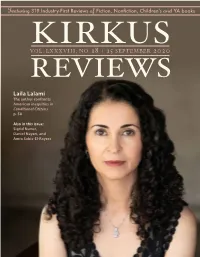

Kirkus Reviews on Our Website by Logging in As a Subscriber

Featuring 319 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books VOL.KIRKUS LXXXVIII, NO. 18 | 15 SEPTEMBER 2020 REVIEWS Laila Lalami The author confronts American inequities in Conditional Citizens p. 58 Also in this issue: Sigrid Nunez, Daniel Nayeri, and Amra Sabic-El-Rayess from the editor’s desk: The Way I Read Now Chairman BY TOM BEER HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # Among the many changes in my daily life this year—working from home, Chief Executive Officer wearing a mask in public, watching too much TV—my changing read- MEG LABORDE KUEHN ing habits register deeply. For one thing, I read on a Kindle now, with the [email protected] Editor-in-Chief exception of the rare galley sent to me at home and the books I’ve made TOM BEER a point of purchasing from local independent bookstores or ordering on [email protected] Vice President of Marketing Bookshop.org. The Kindle was borrowed—OK, confiscated—from my SARAH KALINA boyfriend at the beginning of the pandemic, when I left dozens of advance [email protected] reader copies behind at the office and accepted the reality that digital gal- Managing/Nonfiction Editor ERIC LIEBETRAU leys would be a practical necessity for the foreseeable future. I can’t say that I [email protected] love reading on my “new” Kindle—I’m still a sucker for physical books after Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK all these years—but I’ll admit that it fulfills its purpose efficiently. And I do [email protected] Tom Beer rather enjoy the instant gratification of going on NetGalley or Edelweiss Young Readers’ Editor VICKY SMITH and dispatching multiple books to my device in one fell swoop—a harmless [email protected] form of bingeing that affords a little dopamine rush. -

90 Vjet Kontrolli I Lartë I Shtetit

KALIOPI NASKA BUJAR LESKAJ 1925 KLSH 902015 90 VJET KONTROLLI I LARTË I SHTETIT Tiranë, 2015 Prof. dr. Kaliopi Naska Dr. Bujar Leskaj 90 Vjet Kontrolli i Lartë i Shtetit 1925 - 2015 Tiranë, 2015 1 Ky album është përgatitur në kuadrin e 90 vjetorit të Kontrollit të Lartë të Shtetit Autorë: Prof. dr. Kaliopi Naska Dr. Bujar Leskaj Arti grafik: DafinaKopertina: Stojko Kozma Kondakçiu Tonin Vuksani © Copyright: Kontrolli i Lartë i Shtetit Seria: botime KLSH - 16/2015/51 ISBN: 978-9928-159-41-0 Shtypur në shtypshkronjën: “Classic PRINT” Printing & Publishing Home Tiranë, 2015 2 SHPALLJA E PAVARËSISË DHE ELEMENTË TË KËSHILLIT KONTROLLUES 1912 – 1924 Qeveria e Vlorës dhe fillesat e Këshillit Kontrollues Akti i Shpalljes së Pavarësisë së Shqipërisë. Vlorë 28 nëntor 1912 Ismail Qemal Vlora Themelues i Shtetit Shqiptar Ismail Qemali duke përshëndetur popullin e Vlorës, në ceremoninë e 1-vjetorit të Pavarësisë, Vlorë 2013 Më 28 nëntor 1912 në mbledhjen e parë t i të Kuvendit Kombëtar të Vlorës u nënshkrua nga t e t delegatët Deklarata e Pavarësisë së Shqipërisë. h S i ë rt 90 vjet Kontrolli i La 3 Delegatët e Kuvendit të Vlorës Firmëtarët e Pavarësisë së Shqipërisë: Ismail Kemal Beu, Ilias bej Vrioni, Hajredin bej Cakrani, Xhelal bej Skrapari (Koprencka), Dud (Jorgji) Karbunara, Taq (Dhimitër) Tutulani, Myfti Vehbi Efendiu (Agolli), Abas Efendi (Çelkupa), Mustafa Agai (Hanxhiu), Dom Nikoll Kaçorri, Shefqet bej Daiu, Lef Nosi, Qemal Beu (Karaosmani), Midhat bej Frashëri, Veli Efendiu (Harçi), Elmas Efendiu (Boce), Rexhep Beu (Mitrovica), Bedri Beu (Pejani), Salih Xhuka (Gjuka), Abdi bej Toptani, Mustafa Asim Efendiu (Kruja), Kemal Beu (Mullaj), Ferid bej Vokopola, Nebi Efendi Sefa (Lushnja), Zyhdi Beu (Ohri), Dr. -

The Bear in Eurasian Plant Names

Kolosova et al. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine (2017) 13:14 DOI 10.1186/s13002-016-0132-9 REVIEW Open Access The bear in Eurasian plant names: motivations and models Valeria Kolosova1*, Ingvar Svanberg2, Raivo Kalle3, Lisa Strecker4,Ayşe Mine Gençler Özkan5, Andrea Pieroni6, Kevin Cianfaglione7, Zsolt Molnár8, Nora Papp9, Łukasz Łuczaj10, Dessislava Dimitrova11, Daiva Šeškauskaitė12, Jonathan Roper13, Avni Hajdari14 and Renata Sõukand3 Abstract Ethnolinguistic studies are important for understanding an ethnic group’s ideas on the world, expressed in its language. Comparing corresponding aspects of such knowledge might help clarify problems of origin for certain concepts and words, e.g. whether they form common heritage, have an independent origin, are borrowings, or calques. The current study was conducted on the material in Slavonic, Baltic, Germanic, Romance, Finno-Ugrian, Turkic and Albanian languages. The bear was chosen as being a large, dangerous animal, important in traditional culture, whose name is widely reflected in folk plant names. The phytonyms for comparison were mostly obtained from dictionaries and other publications, and supplemented with data from databases, the co-authors’ field data, and archival sources (dialect and folklore materials). More than 1200 phytonym use records (combinations of a local name and a meaning) for 364 plant and fungal taxa were recorded to help find out the reasoning behind bear-nomination in various languages, as well as differences and similarities between the patterns among them. Among the most common taxa with bear-related phytonyms were Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (L.) Spreng., Heracleum sphondylium L., Acanthus mollis L., and Allium ursinum L., with Latin loan translation contributing a high proportion of the phytonyms. -

The Tim Ferriss Show Transcripts Episode 98: Robert Rodriguez Show Notes and Links at Tim.Blog/Podcast

The Tim Ferriss Show Transcripts Episode 98: Robert Rodriguez Show notes and links at tim.blog/podcast Tim Ferriss: Hello, ladies and germs, puppies and kittens. Meow. This is Tim Ferriss and welcome to another episode of the Tim Ferriss Show, where it is my job to deconstruct world class performers, to teas out the routines, the habits, the books, the influences, everything that you can use, that you can replicated from their best practices. And this episode is a real treat. If you loved the Arnold Schwarzenegger or Jon Favreau or Matt Mullenweg episodes, for instance, you are going to love this one. We have a film director, screen writer, producer, cinematographer, editor, and musician. His name is Robert Rodriguez. His story is so good. While he was a student at University of Texas at Austin, he wrote the script to his first feature film when he was sequestered in a drug research facility as a paid subject in a clinical experiment. So he sold his body for science so that he could make art. And that paycheck covered the cost of shooting his film. Now, what film was that? The film was Element Mariachi, which went on to win the coveted Audience Award at Sundance Film Festival and became the lowest budget movie ever released by a major studio. He went on then, of course, to write and produce a lot, and direct and edit and so on, a lot of films. He’s really a jack of all trades, master of many because he’s had to operate with such low budgets and be so resourceful. -

Ligjvënësit Shqipëtarë Në Vite

LIGJVËNËSIT SHQIPTARË NË VITE Viti 1920 Këshilli Kombëtar i Lushnjës (Senati) Një dhomë, 37 deputetë 27 mars 1920–20 dhjetor 1920 Zgjedhjet u mbajtën më 31 janar 1920. Xhemal NAIPI Kryetar i Këshillit Kombëtar (1920) Dhimitër KACIMBRA Kryetar i Këshillit Kombëtar (1920) Lista emërore e senatorëve 1. Abdurrahman Mati 22. Myqerem HAMZARAJ 2. Adem GJINISHI 23. Mytesim KËLLIÇI 3. Adem PEQINI 24. Neki RULI 4. Ahmet RESULI 25. Osman LITA 5. Bajram bej CURRI 26. Qani DISHNICA 6. Bektash CAKRANI 27. Qazim DURMISHI 7. Beqir bej RUSI 28. Qazim KOCULI 8. Dine bej DIBRA 29. Ramiz DACI 9. Dine DEMA 30. Rexhep MITROVICA 10. Dino bej MASHLARA 31. Sabri bej HAFIZ 11. Dhimitër KACIMBRA 32. Sadullah bej TEPELENA 12. Fazlli FRASHËRI 33. Sejfi VLLAMASI 13. Gjergj KOLECI 34. Spiro Jorgo KOLEKA 14. Halim bej ÇELA 35. Spiro PAPA 15. Hilë MOSI 36. Shefqet VËRLACI 16. Hysein VRIONI 37. Thanas ÇIKOZI 17. Irfan bej OHRI 38. Veli bej KRUJA 18. Kiço KOÇI 39. Visarion XHUVANI 19. Kolë THAÇI 40. Xhemal NAIPI 20. Kostaq (Koço) KOTA 41. Xhemal SHKODRA 21. Llambi GOXHAMANI 42. Ymer bej SHIJAKU Viti 1921 Këshilli Kombëtar/Parlamenti Një dhomë, 78 deputetë 21 prill 1921–30 shtator 1923 Zgjedhjet u mbajtën më 5 prill 1921. Pandeli EVANGJELI Kryetar i Këshillit Kombëtar (1921) Eshref FRASHËRI Kryetar i Këshillit Kombëtar (1922–1923) 1 Lista emërore e deputetëve të Këshillit Kombëtar (Lista pasqyron edhe ndryshimet e bëra gjatë legjislaturës.) 1. Abdyl SULA 49. Mehdi FRASHËRI 2. Agathokli GJITONI 50. Mehmet PENGILI 3. Ahmet HASTOPALLI 51. Mehmet PILKU 4. Ahmet RESULI 52. Mithat FRASHËRI 5.