Aeneid VI and Medieval Views of Dreaming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History and Vision in Byron, the Shelleys, and Keats Timothy Ruppert

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 2008 "Is Not the Past All Shadow?": History and Vision in Byron, the Shelleys, and Keats Timothy Ruppert Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Ruppert, T. (2008). "Is Not the Past All Shadow?": History and Vision in Byron, the Shelleys, and Keats (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1132 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “IS NOT THE PAST ALL SHADOW?”: HISTORY AND VISION IN BYRON, THE SHELLEYS, AND KEATS A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Timothy Ruppert March 2008 Copyright by Timothy Ruppert 2008 “IS NOT THE PAST ALL SHADOW?”: HISTORY AND VISION IN BYRON, THE SHELLEYS, AND KEATS By Timothy Ruppert Approved March 25, 2008 _____________________________ _____________________________ Daniel P. Watkins, Ph.D. Jean E. Hunter , Ph.D. Professor of English Professor of History (Dissertation Director) (Committee Member) _____________________________ _____________________________ Albert C. Labriola, Ph.D. Magali Cornier Michael, Ph.D. Professor of English Professor of English (Committee Member) (Chair, Department of English) _____________________________ Albert C. Labriola, Ph.D. Dean, McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Professor of English iii ABSTRACT “IS NOT THE PAST ALL SHADOW?”: HISTORY AND VISION IN BYRON, THE SHELLEYS, AND KEATS By Timothy Ruppert March 2008 Dissertation Supervised by Professor Daniel P. -

Ralph Hexter

Ralph Hexter What was the Trojan Horse Made Of?: Interpreting Vergil 's Aeneid The most startling feature of the Aeneid's narrative economy is the flash- back represented by books 2 and 3, the account of the fall of Troy and then of Aeneas's wanderings told in Carthage by Aeneas to Dido. Star- tling it is not in the context of Vergilian imitation of Homer: Aeneas tells his story to Dido as Odysseus had told parts of his to the Phaeacians in the Odyssey. 1 But while the Odyssey serves as a rich subtext for the Aeneid, it does not serve readers well if it dulls us to what is novel and, in my view, most characteristically Vergilian about the Roman poet's use of inset narrative, which he doubles or squares. For just as Aeneas's narrative to Dido is set near the beginning of Vergil's narrative to us, as the second and third of twelve books, so near the beginning of Aeneas's narrative we have the account of Sinon's2 deception of the Trojans-by means of storytelling-which leads to their undoing as they accept the Trojan horse into the city. This is a short circuit of narrative and interpretation that no listener or interpreter can overlook. For me, it is the primal scene of narration and misinterpretation in the Aeneid. 3 That this inner scene of narrative deception and misinterpretation is itself part of Aeneas's tale to Dido, which in different ways and for very different reasons leads to her undoing, and that Aeneas's account and Dido's suicide are in turn set within Vergil's narrative to us, has profound ramifications for our understanding of Vergil's text and of our own role and responsibilities as readers. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION The aim of this study is to examine how the works of the Latin poet Virgil were taught in the schools of New South Wales, Australia, throughout the twentieth century, and beyond, despite the enormous social and educational changes over that period which challenged the survival of Latin as a subject in the school curriculum. To observe the teaching of Virgil’s poetry, in a time and place so removed from its origins, offers an opportunity to study the survival of an educational tradition of great antiquity, in a context never envisaged by students of Virgil in earlier centuries and seldom considered by scholars today. The teaching of Virgil in an Australian context has been overlooked in our own time, both by those writing on the reception of Virgil and by those investigating the place of Latin in modern education. A major work on the reception of Virgil in the twentieth century, Theodore Ziolkowski’s Virgil and the Moderns (Princeton 1993),1 illustrates the impact of Virgil on the twentieth century public with reference to the lavish celebrations held in many parts of the world in 1930 to mark two thousand years since the poet’s birth. He lists the outpouring of Virgil–centred publications and activities, including some by and for secondary school students, that took place in Italy, the United States, Mexico, Ecuador, France, Germany and South 1 described by Duncan Kennedy as “the point of departure for future studies of Virgil’s impact on the literature of the twentieth century” in his essay “Modern receptions and their interpretative implications”, The Cambridge Companion to Virgil, ed. -

Killing Turnus: a Reading of Aeneas, Man of Action

KILLING TURNUS: A READING OF AENEAS, MAN OF ACTION by Andrew Jason Korzeniewski BA, Villanova University, 1998 MA, Villanova University, 2005 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2014 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Andrew Jason Korzeniewski It was defended on November 25, 2014 and approved by Harry C. Avery, PhD, Professor, Classics Nicholas F. Jones, PhD, Professor, Classics Dennis O. Looney, PhD, Professor, French and Italian Dissertation Advisor: D. Mark Possanza, PhD, Chairman, Classics ii Copyright © by Andrew Jason Korzeniewski 2014 iii KILLING TURNUS: A READING OF AENEAS, MAN OF ACTION Andrew Jason Korzeniewski, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2014 As repeatedly reiterated, Aeneas’ destiny is to found Rome, yet he frequently ignores said mission, choosing instead to live and act in the present. In the Aeneid, how do we reconcile human choice in a world where there is a fated plan? Vergil does not want the reader to write off human decision making or human personality as irrelevant due to some sort of divine sphere forcing a preordained fate; rather, there are different levels that the action of the Aeneid moves on: The divine (i.e., the mythological, poetic level requiring the action to unfold in accordance with the fated destiny of Rome); the human (i.e., the psychological dimension of characters themselves); and the crucial moments at which the two interact. This dissertation will study Vergil’s multiple track arrangement to demonstrate how Aeneas’ actions the night Troy burns reveal that his personality is not yet ready to accept his mission and act in accordance with the poetic level action of the poem. -

The Allegory of the Golden Bough

Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange Faculty Publications Classics 1995 The Allegory of the Golden Bough Clifford Weber Kenyon College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/classics_pubs Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Weber, Clifford, "The Allegory of the Golden Bough" (1995). Faculty Publications. Paper 11. https://digital.kenyon.edu/classics_pubs/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ALLEGORY OF THE GOLDEN BOUGH Author(s): Clifford Weber Source: Vergilius (1959-), Vol. 41 (1995), pp. 3-34 Published by: The Vergilian Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41587127 . Accessed: 10/10/2014 09:44 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Vergilian Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Vergilius (1959-). http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 138.28.20.205 on Fri, 10 Oct 2014 09:44:22 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE ALLEGORY OF THE GOLDEN BOUGH I Not too many years ago, an essay bearing the title above would have requiredan apology. -

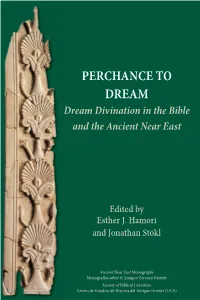

Dream Divination in the Bible and the Ancient Near East

PERCHANCE TO DREAM: DREAM DIVINATION DIVINATION DREAM DREAM: TO PERCHANCE IN THE BIBLE AND THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST NEAR ANCIENT THE AND BIBLE THE IN is book examines the interpretation of dreams that were thought to contain divine messages. Each essay addresses questions about dream divination itself within a speci c text or corpus, considering issues such as agency, authority, veri cation, incubation, and literary and political function. Franziska Ede, Esther J. Hamori, Koowon Kim, Christopher Metcalf, Alice Mouton, Scott B. Noegel, Andrew B. Perrin, Stephen C. Russell, Jonathan Stökl, and Haim Weiss contribute essays to this collection, which presents a snapshot of current scholarly ideas about dream divination in a range of ancient Near Eastern, eastern PERCHANCE TO Mediterranean, and early Jewish texts, including the Bible, the Talmud, and writings from Canaan, Mesopotamia, and Hittite Anatolia. DREAM ESTHER HAMORI is Associate Professor of Hebrew Bible at Union eological Seminary in New York. She is the author of Women’s Dream Divination in the Bible Divination in Biblical Literature: Prophecy, Necromancy, and Other Arts of Knowledge (Yale University Press). and the Ancient Near East JONATHAN STÖKL is Lecturer in Hebrew Bible/Old Testament at King’s College London. He is the author of Prophecy in the Ancient Near East: A Philological and Sociological Comparison (Brill). Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Hamori Society of Biblical Literature Stökl Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) Edited by Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-287-4) available at Esther J. Hamori http://www.sbl-site.org/publications/Books_ANEmonographs.aspx Cover photo: Zev Radovan/BibleLandPictures.com and Jonathan Stökl Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) Table of Contents Perchance to Dream 1 Esther J. -

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works Title What Was The Trojan Horse Made Of?: Interpreting Virgil’s Aeneid Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1h5926jd Journal Yale Journal of Criticism, 3(2) ISSN 0893-5378 Author Hexter, Ralph Jay Publication Date 1990-04-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Ralph Hexter What was the Trojan Horse Made Of?: Interpreting Vergil 's Aeneid The most startling feature of the Aeneid's narrative economy is the flash- back represented by books 2 and 3, the account of the fall of Troy and then of Aeneas's wanderings told in Carthage by Aeneas to Dido. Star- tling it is not in the context of Vergilian imitation of Homer: Aeneas tells his story to Dido as Odysseus had told parts of his to the Phaeacians in the Odyssey. 1 But while the Odyssey serves as a rich subtext for the Aeneid, it does not serve readers well if it dulls us to what is novel and, in my view, most characteristically Vergilian about the Roman poet's use of inset narrative, which he doubles or squares. For just as Aeneas's narrative to Dido is set near the beginning of Vergil's narrative to us, as the second and third of twelve books, so near the beginning of Aeneas's narrative we have the account of Sinon's2 deception of the Trojans-by means of storytelling-which leads to their undoing as they accept the Trojan horse into the city. This is a short circuit of narrative and interpretation that no listener or interpreter can overlook. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced firom the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly firom the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be firom any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing firom left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms international A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 Nortti Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor, fVII 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9219038 “Aeneid” VI 724-899: The myth of the Aeterna regna Toptsi, Urania Molyviati, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1992 UMI 300 N. -

Cultural Memory and Imagination: Dreams and Dreaming in the Roman Empire 31 Bc – Ad 200

CULTURAL MEMORY AND IMAGINATION: DREAMS AND DREAMING IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE 31 BC – AD 200 by JULIETTE GRACE HARRISSON A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Institute of Archaeology and Antiquity College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham September 2009 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis takes Assmann’s theory of cultural memory and applies it to an exploration of conceptualisations of dreams and dreaming in the early Roman Empire (31 BC – AD 200). Background information on dreams in different cultures, especially those closest to Rome (the ancient Near East, Egypt and Greece) is provided, and dream reports in Greco-Roman historical and imaginative literature are analysed. The thesis concludes that dreams were considered to offer a possible connection with the divine within the cultural imagination in the early Empire, but that the people of the second century AD, which has sometimes been called an ‘age of anxiety’, were no more interested in dreams or dream revelation than Greeks and Romans of other periods. -

A Structural Analysis and Visual Abstraction of the Pictorial in the Aeneid, I-Vi

A STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS AND VISUAL ABSTRACTION OF THE PICTORIAL IN THE AENEID, I-VI by RAYFORD WESLEY SHAW submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF LITERATURE AND PHILOSOPHY in the subject HISTORY OF ART at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA PROMOTER: PROF EA MARE JOINT PROMOTER: DR SGI DAMBE JUNE 2000 Title: A STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS AND VISUAL ABSTRACTION OF THE PICTORIAL IN THE AENEID, I-VI Summary: The pictorial elements of the first six books of the Aeneid can be evidenced through an examination of its structural components. With commentaries on such literary devices as parallels and antipodes, interwoven themes, cyclic patterns, and strategic placement of words in the text, three genres of painting are treated individually in Chapter 1 to illustrate the poet's consistency of design and to prove him a craftsman of the visual arts. In the first division, "Cinematic progression," attention is directed to the language which conveys movement and frequentative action, with special emphasis placed on specific passages whose verbal components possess sculptural or third-dimensional traits and contribute to the "spiral" and "circle" motifs, the appropriate visual agents for animation. Depiction of mythological subjects comprises the second division entitled "Cameos and snapshots." Three selections, dubbed monstra, are explicated with such cross references as to illustrate the poet's use of epithets which he distributes passim to elicit verbal echoes of other passages. The final division, "The Vergilian landscape," addresses two major themes, antithetical in nature, the martial and the pastoral. Their sequential juxtaposition in the text renders a marked contrast in mood which is manifested pictorially in the transition from darkness to light. -

ELENA ERMOLAEVA St Petersburg State University, Russia Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies, University of Helsinki, Finland

DOI: http://doi.org/10.22364/av5.08 ELENA ERMOLAEVA St Petersburg State University, Russia Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies, University of Helsinki, Finland THE GATES OF HORN AND IVORY AND THE VERB ΕΛΕΦΑΙΡΟΜΑΙ (Od. 19, 560–569) Brief summary This article is dedicated to the rare verb ἐλεφαίρομαι, the key word of the enigmatic passage about the gates of horn and ivory, and Penelopa’s false or true dreams (Od. 19, 560–569). In Iliad 23, 388 and Hesiod’s Theogony 330, only two other available instances, ἐλεφαίρομαι undoubtedly means ‘to inflict harm, to damage’. The aim of this contribution is to show that the meaning ‘to cheat, to deceive’ for ἐλεφαίρομαι might have been invented by lexicographers based on a misreading of the passage in Odyssey 19 under the influence of later literary allusions and interpretations of the famous excerpt. Keywords: Homer, Odyssey, ἐλεφαίρομαι, paronomasia, lexicographic tradition, literary allusions. This article discusses the old rare epic verb ἐλεφαίρομαι, re-evaluat- ing its meaning and re-assessing its lexicographic tradition. In Homer and Hesiod The verb ἐλεφαίρομαι is available in Greek literature only in three instances. In two of these, the verb means ‘to inflict harm, to damage’ and seems to be a more expressive synonym of βλάπτω ‘to harm, da mage’. II. 23, 388, on the chariot race: 384 ὅς ῥά οἱ ἐκ χειρῶν ἔβαλεν μάστιγα φαεινήν. τοῖο δ’ ἀπ’ ὀφθαλμῶν χύτο δάκρυα χωομένοιο, οὕνεκα τὰς μὲν ὅρα ἔτι καὶ πολὺ μᾶλλον ἰούσας, οἳ δέ οἱ ἐβλάφθησαν ἄνευ κέντροιο θέοντες. οὐδ› ἄρ› Ἀθηναίην ἐλεφηράμενος λάθ› Ἀπόλλων Τυδεΐδην, μάλα δ› ὦκα μετέσσυτο ποιμένα λαῶν, 391 δῶκε δέ οἱ μάστιγα, μένος δ’ ἵπποισιν ἐνῆκεν·1 XCI 91 ELENA ERMOLAEVA Apollo … dashed the shining whip from his hands, so that the tears began to stream from his eyes, for his anger as he watched how the mares of Eumelos drew far ahead of him while his own horses ran without the whip and were slowed.2 Yet Athene did not fail to see the foul play of Apollo on Tydeus son. -

Displacement in Frank Mcguinness' and Michael Longley's

DISPLACEMENT IN FRANK MCGUINNESS AND MICHAEL LONGLEY A PLACE ELSEWHERE: DISPLACEMENT IN FRANK MCGUINNESS' AND MICHAEL LONGLEY'S RESPONSE TO THE NORTHERN IRISH 'TROUBLES' By MICHAEL PATRICK LAPOINTE, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University (c) Copyright by Michael Patrick Lapointe, August 1994 MASTER OF ARTS (1994) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (English) Hamilton l Ontario TITLE: A Place. Elsewhere: Displacement in Frank McGuinness I and Michael Longley/s Response to the Northern Irish 'Troubles' AUTHOR: Michael Patrick Lapointe I B.A. (University of Western Ontario) SUPERVISOR: Professor Brian John NUMBER OF PAGES: VI 95 ii ABSTRACT To date, Northern Ireland's Frank McGuinness and Michael Longley have received meagre critical attention from scholars. Although it has often been assumed by certain artists and critics that the mixing of art and politics is merely a tool for propagandists, McGuinness' plays, Carthaginians and Someone Who'll Watch Over Me, and Longley's poems concerning the Troubles illustrate a healthy intersection of literature with politics. This thesis attempts to analyze how these writers use displacement or imaginative distance as a strategy for illuminating the political and cultural contexts of the North. This indirect engagement in its myriad of forms reflects McGuinness and Longley's quest for a creative realm of displaced perspectives--a place elsewhere. Longley and McGuinness write about their own conscious experiences and those of their various communities through frameworks that are mythically, historically, geographically, and intertextually remote. Both artists seek to render conditions in Northern Ireland symbolically and, thereby, circumvent political ideologies and posit alternative visions to conflict and violence.