China Diary Copy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Imagining Ritual and Cultic Practice in Koguryŏ Buddhism

International Journal of Korean History (Vol.19 No.2, Aug. 2014) 169 Imagining Ritual and Cultic Practice in Koguryŏ Buddhism Richard D. McBride II* Introduction The Koguryŏ émigré and Buddhist monk Hyeryang was named Bud- dhist overseer by Silla king Chinhŭng (r. 540–576). Hyeryang instituted Buddhist ritual observances at the Silla court that would be, in continually evolving forms, performed at court in Silla and Koryŏ for eight hundred years. Sparse but tantalizing evidence remains of Koguryŏ’s Buddhist culture: tomb murals with Buddhist themes, brief notices recorded in the History of the Three Kingdoms (Samguk sagi 三國史記), a few inscrip- tions on Buddhist images believed by scholars to be of Koguryŏ prove- nance, and anecdotes in Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms (Samguk yusa 三國遺事) and other early Chinese and Japanese literary sources.1 Based on these limited proofs, some Korean scholars have imagined an advanced philosophical tradition that must have profoundly influenced * Associate Professor, Department of History, Brigham Young University-Hawai‘i 1 For a recent analysis of the sparse material in the Samguk sagi, see Kim Poksun 金福順, “4–5 segi Samguk sagi ŭi sŭngnyŏ mit sach’al” (Monks and monasteries of the fourth and fifth centuries in the Samguk sagi). Silla munhwa 新羅文化 38 (2011): 85–113; and Kim Poksun, “6 segi Samguk sagi Pulgyo kwallyŏn kisa chonŭi” 存疑 (Doubts on accounts related to Buddhism in the sixth century in the Samguk sagi), Silla munhwa 新羅文化 39 (2012): 63–87. 170 Imagining Ritual and Cultic Practice in Koguryŏ Buddhism the Sinitic Buddhist tradition as well as the emerging Buddhist culture of Silla.2 Western scholars, on the other hand, have lamented the dearth of literary, epigraphical, and archeological evidence of Buddhism in Kogu- ryŏ.3 Is it possible to reconstruct illustrations of the nature and characteris- tics of Buddhist ritual and devotional practice in the late Koguryŏ period? In this paper I will flesh out the characteristics of Buddhist ritual and devotional practice in Koguryŏ by reconstructing its Northeast Asian con- text. -

Chinese Models for Chōgen's Pure Land Buddhist Network

Chinese Models for Chōgen’s Pure Land Buddhist Network Evan S. Ingram Chinese University of Hong Kong The medieval Japanese monk Chōgen 重源 (1121–1206), who so- journed at several prominent religious institutions in China during the Southern Song, used his knowledge of Chinese religious social or- ganizations to assist with the reconstruction of Tōdaiji 東大寺 after its destruction in the Gempei 源平 Civil War. Chōgen modeled the Buddhist societies at his bessho 別所 “satellite temples,” located on estates that raised funds and provided raw materials for the Tōdaiji reconstruction, upon the Pure Land societies that financed Tiantai天 台 temples in Ningbo 寧波 and Hangzhou 杭州. Both types of societ- ies formed as responses to catastrophes, encouraged diverse mem- berships of lay disciples and monastics, constituted geographical networks, and relied on a two-tiered structure. Also, Chōgen devel- oped Amidabutsu 阿弥陀仏 affiliation names similar in structure and function to those used by the “People of the Way” (daomin 道民) and other lay religious groups in southern China. These names created a collective identity for Chōgen’s devotees and established Chōgen’s place within a lineage of important Tōdaiji persons with the help of the Hishō 祕鈔, written by a Chōgen disciple. Chōgen’s use of religious social models from China were crucial for his fundraising and leader- ship of the managers, architects, sculptors, and workmen who helped rebuild Tōdaiji. Keywords: Chogen, Todaiji, Song Buddhism, Pure Land Buddhism, Pure Land society he medieval Japanese monk Chōgen 重源 (1121–1206) earned Trenown in his middle years as “the monk who traveled to China on three occasions,” sojourning at several of the most prominent religious institutions of the Southern Song (1127–1279), including Tiantaishan 天台山 and Ayuwangshan 阿育王山. -

Chan Rhetoric of Uncertainty in the Blue Cliff Record

Chan Rhetoric of Uncertainty in the Blue Cliff Record Chan Rhetoric of Uncertainty in the Blue Cliff Record Sharpening a Sword at the Dragon Gate z STEVEN HEINE 1 1 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America. © Oxford University Press 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file at the Library of Congress ISBN 978–0–19–939776–1 (hbk); 978–0–19–939777–8 (pbk) 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 Printed by Webcom, Canada Contents Preface vii 1. Prolegomenon to a New Hermeneutic: On Being Uncertain about Uncertainty 1 2. Entering the Dragon Gate: Textual Formation in Historical and Rhetorical Contexts 46 3. -

The Revival of Tiantai Buddhism in the Late Ming: on the Thought of Youxi Chuandeng 幽溪傳燈 (1554-1628)

The Revival of Tiantai Buddhism in the Late Ming: On the Thought of Youxi Chuandeng 幽溪傳燈 (1554-1628) Yungfen Ma Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2011 © 2011 Yungfen Ma All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The Revival of Tiantai Buddhism in the Late Ming: On the Thought of Youxi Chuandeng 幽溪傳燈 (1554-1628) Yungfen Ma This dissertation is a study of Youxi Chuandeng’s (1554-1628) transformation of “Buddha-nature includes good and evil,” also known as “inherent evil,” a unique idea representing Tiantai’s nature-inclusion philosophy in Chinese Buddhism. Focused on his major treatise On Nature Including Good and Evil, this research demonstrates how Chuandeng, in his efforts to regenerate Tiantai, incorporated the important intellectual themes of the late Ming, especially those found in the Śūraṃgama Sūtra. In his treatise, Chuandeng systematically presented his ideas on doctrinal classification, the principle of nature-inclusion, and the practice of the Dharma-gate of inherent evil. Redefining Tiantai doctrinal classification, he legitimized the idea of inherent evil to be the highest Buddhist teaching and proved the superiority of Buddhism over Confucianism. Drawing upon the notions of pure mind and the seven elements found in the Śūraṃgama Sūtra, he reinterpreted nature-inclusion and the Dharma-gate of inherent evil emphasizing inherent evil as pure rather than defiled. Conversely, he reinterpreted the Śūraṃgama Sūtra by nature-inclusion. Chuandeng incorporated Confucianism and the Śūraṃgama Sūtra as a response to the dominating thought of his day, this being the particular manner in which previous Tiantai thinkers upheld, defended and spread Tiantai. -

Daoism in the Twentieth Century: Between Eternity and Modernity

UC Berkeley GAIA Books Title Daoism in the Twentieth Century: Between Eternity and Modernity Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/13w4k8d4 Authors Palmer, David A. Liu, Xun Publication Date 2012-02-15 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Daoism in the Twentieth Century Between Eternity and Modernity Edited by David A. Palmer and Xun Liu Published in association with the University of California Press “This pioneering work not only explores the ways in which Daoism was able to adapt and reinvent itself during China’s modern era, but sheds new light on how Daoism helped structure the development of Chinese religious culture. The authors also demon- strate Daoism’s role as a world religion, particularly in terms of emigration and identity. The book’s sophisticated approach transcends previous debates over how to define the term ‘Daoism,’ and should help inspire a new wave of research on Chinese religious movements.” PAUL R. KATZ, Academia Sinica, Taiwan In Daoism in the Twentieth Century an interdisciplinary group of scholars ex- plores the social history and anthropology of Daoism from the late nineteenth century to the present, focusing on the evolution of traditional forms of practice and community, as well as modern reforms and reinventions both within China and on the global stage. Essays investigate ritual specialists, body cultivation and meditation traditions, monasticism, new religious movements, state-spon- sored institutionalization, and transnational networks. DAVID A. PALMER is a professor of sociology at Hong Kong University. -

Buddhist Tales of Lü Dongbin

T’OUNG PAO 448 T’oungJoshua Pao 102-4-5 Capitanio (2016) 448-502 www.brill.com/tpao International Journal of Chinese Studies/Revue Internationale de Sinologie Buddhist Tales of Lü Dongbin Joshua Capitanio (University of the West) Abstract During the early thirteenth century, a story began to appear within texts associated with the Chan 禪 Buddhist movement, which portrays an encounter between the eminent transcendent Lü Dongbin 呂洞賓 and the Chan monk Huanglong Huiji 黃龍誨機 that results in Lü abandoning his alchemical techniques of self-cultivation and taking up the practice of Chan. This article traces the development of this tale across a number of Buddhist sources of the late imperial period, and also examines the ways in which later Buddhist and Daoist authors understood the story and utilized it in advancing their own polemical claims. Résumé Au début du treizième siècle apparaît dans les textes du bouddhisme Chan un récit qui met en scène une rencontre entre le célèbre immortel Lü Dongbin et le moine Chan Huanglong Huiji. Au terme de cette rencontre, Lü abandonne ses pratiques alchimiques de perfectionnement de soi et adopte celle de la méditation Chan. Le présent article retrace le développement de ce thème narratif au travers des sources bouddhiques de la fin de l’époque impériale, et examine la manière dont des auteurs bouddhistes et taoïstes ont compris le récit et l’ont manipulé en fonction de leurs propres objectifs polémiques. Keywords Buddhism, Daoism, Chan, neidan, Lü Dongbin * I would like to extend my thanks to two anonymous reviewers who provided helpful com- ments on an earlier draft of this article. -

Religion in Modern Taiwan

00FMClart 7/25/03 8:37 AM Page i RELIGION IN MODERN TAIWAN 00FMClart 7/25/03 8:37 AM Page ii TAIWAN AND THE FUJIAN COAST. Map designed by Bill Nelson. 00FMClart 7/25/03 8:37 AM Page iii RELIGION IN MODERN TAIWAN Tradition and Innovation in a Changing Society Edited by Philip Clart & Charles B. Jones University of Hawai‘i Press Honolulu 00FMClart 7/25/03 8:37 AM Page iv © 2003 University of Hawai‘i Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 08 07 0605 04 03 65 4 3 2 1 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Religion in modern Taiwan : tradition and innovation in a changing society / Edited by Philip Clart and Charles B. Jones. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8248-2564-0 (alk. paper) 1. Taiwan—Religion. I. Clart, Philip. II. Jones, Charles Brewer. BL1975 .R46 2003 200'.95124'9—dc21 2003004073 University of Hawai‘i Press books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Council on Library Resources. Designed by Diane Gleba Hall Printed by The Maple-Vail Book Manufacturing Group 00FMClart 7/25/03 8:37 AM Page v This volume is dedicated to the memory of Julian F. Pas (1929–2000) 00FMClart 7/25/03 8:37 AM Page vi 00FMClart 7/25/03 8:37 AM Page vii Contents Preface ix Introduction PHILIP CLART & CHARLES B. JONES 1. Religion in Taiwan at the End of the Japanese Colonial Period CHARLES B. -

Chronology of Shitao's Life

SHITAO APPENDIX ONE Chronology of Shitao's Life References are given here only for information that is not 6r), as the Shunzhi emperor, accompanied by the appoint- presented elsewhere in this book in fuller form (especially ment of Hong Taiji's younger brother, Dorgon (r 6r 2-50), in Chapters 4-6) and accessible through the index. Here, as regent. as throughout this study, years refer to Chinese lunar years. Most of the places mentioned can be found on r644 Map 3. Where an existing artwork contradicts the dates Fall of Beijing to the Shun regime of Li Zicheng, followed given here for the use of specific signatures and seals, this shortly after by their abandonment of Beijing to Qing will generally mean that I am not convinced of the work's forces. Dorgon proclaimed Qing rule over China in the authenticity (though there will inevitably be cases of over- name of the Shunzhi emperor, who shortly after was sight or ignorance as well). With the existence and loca- brought to Beijing. In south China, resistance to the Man- tion in mainland Chinese libraries of rare publications chus crystallized around different claimants to the Ming and manuscripts by no less than thirty-six of his friends throne, whose regimes are collectively known as the and acquaintances newly established, providing a rich Southern Ming. new vein for biographical research, and with new works by Shitao regularly coming to light, this chronology must r645 be considered provisional) Fall of Nanjing to Qing forces. In Guilin in the ninth r642 month, Zhu Hengjia was attacked and defeated by forces of the Southern Ming Longwu emperor, Zhu Yujian, Shitao was born into the family of the Ming princes of under the command of Qu Shisi, and taken to Fuzhou, Jingjiang, under the name of Zhu Ruoji. -

Crossing Thousands of Li of Waves: the Return of China's Lost Tiantai Texts

JIABS Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 29 Number 1 2006 (2008) The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies (ISSN 0193-600XX) is the organ of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, Inc. It welcomes scholarly contributions pertaining to all facets of Buddhist Studies. EDITORIAL BOARD JIABS is published twice yearly, in the summer and winter. KELLNER Birgit Manuscripts should preferably be sub- KRASSER Helmut mitted as e-mail attachments to: Joint Editors [email protected] as one single file, complete with footnotes and references, BUSWELL Robert in two different formats: in PDF-format, and in Rich-Text-Format (RTF) or Open- CHEN Jinhua Document-Format (created e.g. by Open COLLINS Steven Office). COX Collet GÓMEZ Luis O. Address books for review to: HARRISON Paul JIABS Editors, Institut für Kultur - und Geistesgeschichte Asiens, Prinz-Eugen- VON HINÜBER Oskar Strasse 8-10, AT-1040 Wien, AUSTRIA JACKSON Roger JAINI Padmanabh S. Address subscription orders and dues, KATSURA Shōryū changes of address, and UO business correspondence K Li-ying (including advertising orders) to: LOPEZ, Jr. Donald S. Dr Jérôme Ducor, IABS Treasurer MACDONALD Alexander Dept of Oriental Languages and Cultures SCHERRER-SCHAUB Cristina Anthropole SEYFORT RUEGG David University of Lausanne CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland SHARF Robert email: [email protected] STEINKELLNER Ernst Web: www.iabsinfo.net TILLEMANS Tom Fax: +41 21 692 30 45 ZÜRCHER Erik Subscriptions to JIABS are USD 40 per year for individuals and USD 70 per year for libraries and other institutions. For informations on membership in IABS, see back cover. -

Between One and Many: Multiples, Multiplication and the Huayan Metaphysics

2011 ELSLEY ZEITLIN LECTURE ON CHINESE ARCHAEOLOGY AND CULTURE Between One and Many: Multiples, Multiplication and the Huayan Metaphysics HSUEH-MAN SHEN New York University I. Introduction IN THE EARLY AFTERNOON hours of 25 September 1924, the Leifengta 雷峰塔 Pagoda located on a bluff overlooking the scenic West Lake in present-day Hangzhou collapsed (Fig. 1), revealing multiple copies of the Dharan.i of the Seal on the Casket of the Secret Whole-body Relic of the Essence of All Tathagatas ( s. Sarvatathagatadhis.t.hanahr.dayaguhyadhatu karan.d.amudra- dharan.i; c. Yieqie rulai xin mimi quanshen sheli baoqie yin tuoluoni jing 一切如來心祕密全身舍利寶篋印陀羅尼經, hereafter, Dharan.i Sutra of the Seal on the Casket).1 The printed texts were rolled up and enclosed inside hollow bricks that once formed the upper stories of the pagoda.2 These scrolls commonly bear dedicatory inscriptions referring to Qian Chu 錢俶 (929–88, r. 947–78), the last king of Wuyue 吳越 (907–78), a wealthy independent kingdom covering present-day Zhejiang, Shanghai, and the Read at the Academy 1 November 2011. 1 There are two Chinese translations, one by Amoghavajra (705–74) and the other by Danapala (fl. 982). See Taisho Tripit.aka (hereafter T.), T 1022A.19.710a–712b, T 1022B.19.712b–715a, and T 1023.19.715a–717c. 2 Other treasures of the Leifengta Pagoda would have to wait until the 2001 excavation of the pagoda foundation, at which point archaeologists revealed an underground relic burial. For a report of the excavation, see Zhejiang sheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo (ed.), Leifeng ta yizhi (Beijing, 2005). -

Copyright © Ronald James Dziwenka 2010 a Dissertation

‘THE LAST LIGHT OF INDIAN BUDDHISM’ - THE MONK ZHIKONG IN 14TH CENTURY CHINA AND KOREA by Ronald James Dziwenka ______________________ Copyright © Ronald James Dziwenka 2010 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2010 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Ronald James Dziwenka entitled ‘The Last Light of Indian Buddhism’ – The Monk Zhikong in 14th Century China and Korea and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy ________________________________________________Date: March 5, 2010 Jiang Wu ________________________________________________Date: March 5, 2010 Chia-lin Pao Tao ________________________________________________Date: March 5, 2010 Noel Pinnington ________________________________________________Date: March 5, 2010 Yetta Goodman ________________________________________________Date: March 5, 2010 Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and Recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. ________________________________________________Date: March 5, 2010 Dissertation Director: Jiang Wu 3 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This dissertation has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this dissertation are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgement of source is made. -

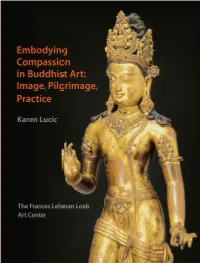

Embodying Compassion in Buddhist Art: Image, Pilgrimage, Practice

Embodying Compassion in Buddhist Art: Image, Pilgrimage, Practice THE FRANCES LEHMAN LOEB ART CENTER Embodying Compassion 1 Embodying Compassion in Buddhist Art: Image, Pilgrimage, Practice Karen Lucic The Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center 2 Embodying Compassion Embodying Compassion 3 Lenders and Donors to the Exhibition Contents American Museum of Natural History, New York 6 Acknowledgments Asia Society, New York 7 Note to the Reader Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art 9 Many Faces, Many Names: Avalokiteshvara, Bodhisattva of Compassion The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 49 Embodying Compassion in Buddhist Art: The Newark Museum Catalogue Entries Princeton University Art Museum 49 Image The Rubin Museum of Art, New York 59 Pilgrimage Daniele Selby ’13 65 Practice 73 Glossary 76 Sources Cited 80 Photo Credits Front cover illustration: Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara (detail), Nepal, The exhibition and publication ofEmbodying Compassion in Transitional period, late 10th–early 11th century; gilt copper alloy with Buddhist Art: Image, Pilgrimage, Practice are supported by inlays of semiprecious stones; 26 3/4 x 11 1/2 x 5 1/4 in.; Asia Society, E. Rhodes & Leona B. Carpenter Foundation; The Henry Luce New York, Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.47. Foundation; ASIANetwork Luce Asian Arts Program; John Stuart Gordon ’00; Elizabeth Kay and Raymond Bal; Ann Kinney Back cover illustration: Kannon (Avalokiteshvara), (detail), Japanese, ’53 and Gilbert Kinney. It is organized by The Frances Lehman Edo period (1615–1868); hanging scroll, ink and color on silk; image: Loeb Art Center and on view from April 23 to June 28, 2015. 61 7/8 x 33 in., mount: 87 7/8 x 39 1/2 in.; Gift of Daniele Selby ’13, The Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College, 2014.20.1.