I Learned to Write Nice As Hell ...Pa's Gonna Be Mad When He Sees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Wreck of the Exxon Valdez: a Case of Crisis Mismanagement

THE WRECK OF THE EXXON VALDEZ: A CASE OF CRISIS MISMANAGEMENT by Sarah J. Clanton A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Communication Division of Communication UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-STEVENS POINT Stevens Point, Wisconsin January 1993 FORMD Report on Oral Defense of Thesis TITLE: __T_h_e_w_r_ec_k_o_f_t_h_e_E_x_x_o_n_v_a_ia_e_z_: _A_c_a_s_e_o_f_c_r_i_·s_i_· s_ Mismanagement AUTHOR: __s_a_r_a_h_J_._c_l_a_n_t_o_n _____________ Having heard an oral defense of the above thesis, the Advisory Committee: ~) Finds the defense of the thesis to be satisfactory and accepts the thesis as submitted, subject to the following recommendation(s), if any: __B) Finds the defense of the thesis to be unsatisfactory and recommends that the defense of the thesis be rescheduled contingent upon: Date: r;:1;;2.- 95' Committee: _....._~__· ___ /_. _....l/AA=--=-'- _ _____,._~_ _,, Advisor ~ J h/~C!.,)~ THE WRECK OF THE EXXON VALDEZ: A CASE OF CRISIS MISMANAGEMENT INDEX I. Introduction A. Exxon's lack of foresight and interest B. Discussion of corporate denial C. Discussion of Burkean theory of victimage D. Statement of hypothesis II. Burke and Freud -Theories of Denial and Scapegoating A. Symbolic interactionism B. Burke's theories of human interaction C. Vaillant's hierarchy D. Burke's hierarchy E. Criteria for a scapegoat F. Denial defined G. Denial of death III. Crisis Management-State of the Art A. Organizational vulnerability B. Necessity for preparation C. Landmark cases-Wisconsin Electric D. Golin Harris survey E. Exxon financial settlement F. Crisis management in higher education G. Rules of crisis management H. Tracing issues and content analysis I. -

The Songs of Bob Dylan

The Songwriting of Bob Dylan Contents Dylan Albums of the Sixties (1960s)............................................................................................ 9 The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963) ...................................................................................................... 9 1. Blowin' In The Wind ...................................................................................................................... 9 2. Girl From The North Country ....................................................................................................... 10 3. Masters of War ............................................................................................................................ 10 4. Down The Highway ...................................................................................................................... 12 5. Bob Dylan's Blues ........................................................................................................................ 13 6. A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall .......................................................................................................... 13 7. Don't Think Twice, It's All Right ................................................................................................... 15 8. Bob Dylan's Dream ...................................................................................................................... 15 9. Oxford Town ............................................................................................................................... -

P20 Layout 1

20 Established 1961 Sunday, August 19 , 2018 Lifestyle Gossip You Me At Six fuse The Weeknd with rock music on new album VI ou Me At Six’s forthcoming sixth album ‘VI’ record, how do we do it and not make it feel like we are a that doesn’t mean it’s any good.” The 27-year-old singer Y sounds like “The Weeknd being smacked in the guitar band?’ “He wasn’t scared and was like, ‘Yeah, let’s compares the band’s transition from ‘Night People’ to ‘VI’ face with rock music”. The ‘Underdog’ hitmak- do that.’ “Whereas some producers are like, ‘Stay in your like the Arctic Monkeys’ journey from 2009 LP ‘Humbug’ ers previously said they hope the record will be lane’, and we are like, ‘Nah, man.’ “Dan has been doing a to 2013’s ‘AM’, arguably their best record to date. He “career-defining” as they admitted to feeling “under- lot of work on Logic (software) and this album has a lot of explained: “I still stand behind ‘Night People’ because it’s whelmed” by 2017’s ‘Night People’, and now they’ve dance songs. “Like The Weeknd being smacked in the something we’ve done. “You know how Arctic Monkeys revealed they weren’t afraid to mix their hip-hop influ- face with rock music. “I think that Dan really encouraged had ‘Humbug’ as a stepping stone before ‘AM’, that’s how I ences, including the ‘Starboy’ rapper, with their guitar that.” Josh previously admitted the band felt they needed feel it was like for us. -

Adéla Jonášová

Wikipedista:Alfi51 Žiji v Českém Těšíně. Aleš Havlíček Jsem důchodce a rád si hraji s počítačem. Články mnou založené Alannah Currie Aldeburgh Angie Dickinson Alexandre Francois Debain Alex Sadkin Andělín Grobelný Adéla Jonášová Anita Carter Axel Stordahl The Beatmen Beatles For Sale Bedřich Havlíček Berthold Bartosch Biela voda (přítok Teplice) Billy Vera Bob Chester Bobbi Kristina Brown Bobby Vee Bobby Vinton Carlene Carter Carl Perkins Chuck Jackson Dana Vrchovská Eydie Gormé Emil Vašek Festival Kino na hranici Flora Murrayová Frankie Avalon Frank P. Banta French press Aleš v roce 2008 George Dunning George Botsford Gene Greene Hal Základní informace David Hans Mrogala Harmonium Harry James Helen Carter Help! (album) Howard Deutch Ida Münzbergová Narození 21. dubna 1951 Ina Ray Hutton Ipeľská pahorkatina Ivana Ostrava, Česko Wojtylová Izabela Trojanowska Jakub Mátl James Scott Žánry pop, blues (hudebník) Jan Hasník Javorianska hornatina Jerzy Povolání hudební skladatel, počítačový Kronhold Jimmy Durante John Keeble José Feliciano Joseph Lamb Judy Clay June Hutton Jungle fanatik a wikipedista Funk Kateřina Kornová Koruna (hudba) Kunešovská Nástroje kytara hornatina Ladislav Báča Largo (Florida) LaVerne Sophia Aktivní roky dosud Andrews Les Brown (hudebník) Let It Be (album) Louis Manžel(ka) Dagmar Krzyžánková Prima Louisa Garrett Andersonová Madelyn Deutch Maggi Hambling Martha a Tena Maxene Angelyn Andrews Děti Aleš, Martin Mezinárodní divadelní festival Na hranici Millicent Garrett Rodiče Bedřich Havlíček, Fawcett Mira Kubasińska Mud -

Old Owenians Newsletter Sept 2014 Draft.Pdf

Old Owenians Newsletter Third Quarter—30th September 2014 Edition 15 A message from our Head… “Dear Old Owenians Firstly, welcome to new members if you’ve signed up to Old Owenians In Touch over the summer and thanks to those of you who’ve updated your details. Our new database has recorded lots of activity and we hope it’ll be an easier way of helping you to find your past peers and enable you to register more detailed information. We’re delighted seven businesses have joined our Old Owenians Business Directory and we’re happy to include more! We also hope to see many of you at our annual Old Owenians Harold Moore Old Owenians Harold Moore Reunion Luncheon in London in October to support our new organiser, Annual Reunion Luncheon Sandyann Cannon (Class of 1985) and MC Perry Offer (Class of 1977). Monday 27th October 2014 Imperial Hotel, August brought an excellent set of examination results in spite of the Russell Square, London, national drop in results for our Years 10, 11, 12 and 13 . Their hard work, and from 11.30am till 4pm the support of dedicated staff and parents, has ensured a truly outstanding, More details on page 2! well-deserved outcome. Key highlights below (further details on our website): 22% of all A-Level entries were awarded the A* grade 86% of all A-Level entries were graded A*, A or B 21 students have confirmed places at Oxford or Cambridge 99.5% of students in Year 11 secured 5 A*-C grades (a new school record), with 96.5% securing 5 A*-C grades when English and Mathematics are included—over 66% of all entries were graded A or A* Also, we’d like to congratulate Old Owenian, Jodie Williams, Class of 2012, who secured silver medals in the Commonwealth Games in July and the European Championships in August in the 200m and a record breaking gold medal in the 4 x 100 relay. -

Environmental Writing and Education

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@USU Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2005 The Search for a Common Language: Environmental Writing and Education Melody Graulich Paul Crumbley Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the Creative Writing Commons, and the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Graulich, M., & Crumbley, P. (2005). The search for a common language: Environmental writing and education. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press Logan. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Search for a Common Language Environmental Writing and Education Edited by Melody Graulich and Paul Crumbley The Search for a Common Language The Search for a Common Language Environmental Writing and Education Edited and with an Introduction by Melody Graulich and Paul Crumbley Utah State University Press Logan, Utah Copyright © 2005 Utah State University Press All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322-7800 www.usu.edu/usupress Poems from “Bestiary” copyright © 2002 by Ken Brewer are printed here with the author’s permission. An earlier version of “What Is the L. A. River?” by Jennifer Price was published in the L. A. Weekly. “The Natural West” by Dan Flores is distilled from The Natural West (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001). -

AA-Postscript.Qxp:Layout 1

36 TUESDAY, AUGUST 12, 2014 LIFESTYLE Gossip Spandau Ballet plan world tour pandau Ballet are planning a world tour next year. The 80s pop stars - fronted by STony Hadley - are set to hit the road in support of their new LP which they are cur- rently recording, their full album for 25 years. Gary Kemp told The Sun: “Everything is back on track. We want to go back on tour. We didn’t patch things up for money but because we had a deep history with each other.” The band - which includes brothers Gary and Martin Kemp, Steve Norman, Tony Hadley and John Keeble - reunited in 2009 after a bitter split for a run of shows and could make £20 million collectively from their proposed 2015 tour. The five band members - who between them produced hits like ‘Gold’ and ‘True’ - split up in 1990 and had not spoken for 20 years after disagreements over royalties. The band have been busy releasing a movie about their musical life titled ‘Soul Boys of The Western World’ which will be available in October. Janet Jackson to release new album this year? anet Jackson is expected to release a new album later this year. The ‘All For JYou’ singer has reportedly been working on an upcoming project and it is said she will pay tribute to her late brother Michael, with plans to cover one of his tracks for the record. A source told The Sun on Sunday newspaper: “The label are really pushing Janet and have made her a priority act for the year, which means a big budget.”It’s the first album she’s released since Michael died in 2009 so she felt it was fitting to include a nod to him. -

Freddie Mercury

1 Tradução Fabiana Barúqui 1ª edição Rio de Janeiro | 2013 CIP-BRASIL. CATALOGAÇÃO-NA-FONTE SINDICATO NACIONAL DOS EDITORES DE LIVROS, RJ. 2 Jones, Lesley-Ann J67f Freedie Mercury/Lesley-Ann Jones; tradução: Fabiana Barúqui. — Rio de Janeiro: BestSeller, 2012.Tradução de: Freddie Mercury : the definitive biographyFormato: ePub Requisitos do sistema: Adobe Digital Editions Modo de acesso: World Wide Web ISBN978-85-7684- 673-4 (recurso eletrônico)1. Mercury, Freddie, 1946-1991. 2. Músicos de rock — Inglaterra — Biografia. 3. Rock — Inglaterra — História. I. Título. 4. Livro eletrônico CDD: 927.8166 CDU: 929:78.067.26 Texto revisado segundo o novo Acordo Ortográfico da Língua Portuguesa. Título original inglês FREDDIE MERCURY: THE DEFINITIVE BIOGRAPHY Copyright © 2011 by Lesley-Ann Jones Copyright da tradução © 2012 by Editora Best Seller Ltda. Publicado primeiramente na Grã-Bretanha em 2011 pela Hodder & Stoughton, um selo da Hachette UK. Capa: Gabinete de Artes Editoração eletrônica da versão impressa: FA Studio Todos os direitos reservados. Proibida a reprodução, no todo ou em parte, sem autorização prévia por escrito da editora, sejam quais forem os meios empregados. Direitos exclusivos de publicação em língua portuguesa para o Brasil adquiridos pela EDITORA BEST SELLER LTDA. Rua Argentina, 171, parte, São Cristóvão Rio de Janeiro, RJ — 20921-380 que se reserva a propriedade literária desta tradução Produzido no Brasil ISBN978-85-7684-673-4 Seja um leitor preferencial Record. Cadastre-se e receba informações sobre nossos lançamentos -

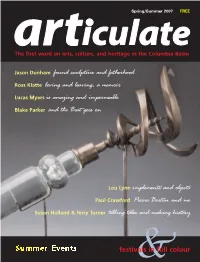

Lou Lynn Implements and Objects Paul Crawford Pierre Berton And

Spring/Summer 2007 FREE The first word on arts, culture, and heritage in the Columbia Basin Jason Dunham found sculpture and fatherhood Ross Klatte loving and leaving, a memoir Lucas Myers is amazing and impermeable Blake Parker and the Beat goes on Lou Lynn implements and objects Paul Crawford Pierre Berton and me Susan Hulland & Terry Turner telling tales and making history festivals& in full colour Fernie Writers Conference July 22-29, 2007 Novel: John Keeble July 27-29 Short Story: Angie Abdou Poetry: Brenda Schmidt Golf: Jeff Wallach Fishing: TBA For tuition and scholarship information see web site www.ferniewriters.org Registration and Lodging (24 hours) 1-888-423-6855 Major sponsor: 2nd tier sponsors: CAPITOL THEATRE The Capitol Theatre Summer Youth Program Presents JACOB TWO TWO MEETS THE HOODED FANG Based on the book by Mordecai Richler Directed by Nicola Harwood Musical Director Bessie Wapp Choreographer Lynette Lightfoot Set by Brent Bukowski Thursday July 26, 2007 7:30pm Friday July 27, 2007 7:30pm Saturday July 28, 2007 7:30pm Saturday July 28, 2007 2:00pm Tickets $12 adult $8 youth $35 family of four Charge by phone Capitol Theatre Box Office 250-352-6363 first word spring/summer 2007 Bringing more colour into your lives contents THIS IS ONE OF THOSE admissions that will really date me, but when I was in the shower this morning I found myself warbling that milestones arts and heritage news 4 tune by Chicago (remember the band with the horn section?), “Colour My World.” No, I hadn’t just been to a 1970s wedding reception or a music festival populated by geezer groups, but there Page 5 meeting place Creston & Kimberley art clubs 5 must have been something subliminal going on. -

An Environmental History of the Kawuneeche Valley and the Headwaters of the Colorado River, Rocky Mountain National Park

An Environmental History of the Kawuneeche Valley and the Headwaters of the Colorado River, Rocky Mountain National Park Thomas G. Andrews Associate Professor of History University of Colorado at Boulder October 3, 2011 Task Agreeement: ROMO-09017 RM-CESU Cooperative Agreement Number: H12000040001 Table of Contents Acknowledgements i Abbreviations Used in the Notes iv Introduction 1 Chapter One: 20 Native Peoples and the Kawuneeche Environment Chapter Two: 91 Mining and the Kawuneeche Environment Chapter Three: 150 Settling and Conserving the Kawuneeche, 1880s-1930s Chapter Four: 252 Consolidating the Kawuneeche Chapter Five: 367 Beaver, Elk, Moose, and Willow Conclusion 435 Bibliography 441 Appendix 1: On “Numic Spread” 477 Appendix 2: Homesteading Data 483 Transcript of Interview with David Cooper 486 Transcript of Interview with Chris Kennedy 505 Transcript of Interview with Jason Sibold 519 i Acknowledgements This report has benefited from the help of many, many people and institutions. My first word of thanks goes to my two research assistants, Daniel Knowles and Brandon Luedtke. Both Dan and Brandon proved indefatigable, poring through archival materials, clippings files, government reports, and other sources. I very much appreciate their resourcefulness, skill, and generosity. I literally could not have completed this report without their hard work. Mark Fiege of Colorado State University roped me into taking on this project, and he has remained a fount of energy, information, and enthusiasm throughout. Maren Bzdek of the Center for Public Lands History handled various administrative details efficiently and with good humor. At the National Park Service, Cheri Yost got me started and never failed to respond to my requests for help. -

Pancho's Racket and the Long Road to Professional Tennis

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2017 Pancho's Racket and the Long Road to Professional Tennis Gregory I. Ruth Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Sports Management Commons Recommended Citation Ruth, Gregory I., "Pancho's Racket and the Long Road to Professional Tennis" (2017). Dissertations. 2848. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/2848 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2017 Gregory I. Ruth LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO PANCHO’S RACKET AND THE LONG ROAD TO PROFESSIONAL TENNIS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN HISTORY BY GREGORY ISAAC RUTH CHICAGO, IL DECEMBER 2017 Copyright by Gregory Isaac Ruth, 2017 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Three historians helped to make this study possible. Timothy Gilfoyle supervised my work with great skill. He gave me breathing room to research, write, and rewrite. When he finally received a completed draft, he turned that writing around with the speed and thoroughness of a seasoned editor. Tim’s own hunger for scholarship also served as a model for how a historian should act. I’ll always cherish the conversations we shared over Metropolis coffee— topics that ranged far and wide across historical subjects and contemporary happenings. -

Bootleg: the Secret History of the Other Recording Industry

BOOTLEG The Secret History of the Other Recording Industry CLINTON HEYLIN St. Martin's Press New York m To sweet D. Welcome to the machine BOOTLEG. Copyright © 1994 by Clinton Heylin. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, address St. Martin's Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010. ISBN 0-312-13031-7 First published in Great Britain by the Penguin Group First Edition: June 1995 10 987654321 Contents Prologue i Introduction: A Boot by Any Other Name ... 5 Artifacts 1 Prehistory: From the Bard to the Blues 15 2 The Custodians of Vocal History 27 3 The First Great White Wonders 41 4 All Rights Reserved, All Wrongs Reversed 71 5 The Smokin' Pig 91 6 Going Underground 105 7 Vicki's Vinyl 129 8 White Cover Folks! 143 9 Anarchy in the UK 163 10 East/West 179 11 Real Cuts at Last 209 12 Complete Control 229 Audiophiles 13 Eraserhead Can Rub You Out 251 14 It Was More Than Twenty Years Ago . 265 15 Some Ultra Rare Sweet Apple Trax 277 16 They Said it Couldn't be Done 291 17 It Was Less Than Twenty Years Ago . 309 18 The Third Generation 319 19 The First Rays of the New Rising Sun 333 20 The Status Quo Re-established 343 21 The House That Apple Built 363 22 Bringing it All Back Home 371 Aesthetics 23 One Man's Boxed-Set (Is Another Man's Bootleg) 381 24 Roll Your Tapes, Bootleggers 391 25 Copycats Ripped Off My Songs 403 Glossary 415 The Top 100 Bootlegs 417 Bibliography 420 Notes 424 Index 429 Acknowledgements 442 Prologue In the summer of 1969, in a small cluster of independent LA record stores, there appeared a white-labelled two-disc set housed in a plain cardboard sleeve, with just three letters hand-stamped on the cover - GWW.