A Foreigner Returning from a Trip to the Third Reich When Asked Who Really Ruled There, Answered: ‘Fear’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Part 05.Indd

PART MISCELLANEOUS 5 TOPICS Awards and Honours Y NATIONAL AWARDS NATIONAL COMMUNAL Mohd. Hanif Khan Shastri and the HARMONY AWARDS 2009 Center for Human Rights and Social (announced in January 2010) Welfare, Rajasthan MOORTI DEVI AWARD Union law Minister Verrappa Moily KOYA NATIONAL JOURNALISM A G Noorani and NDTV Group AWARD 2009 Editor Barkha Dutt. LAL BAHADUR SHASTRI Sunil Mittal AWARD 2009 KALINGA PRIZE (UNESCO’S) Renowned scientist Yash Pal jointly with Prof Trinh Xuan Thuan of Vietnam RAJIV GANDHI NATIONAL GAIL (India) for the large scale QUALITY AWARD manufacturing industries category OLOF PLAME PRIZE 2009 Carsten Jensen NAYUDAMMA AWARD 2009 V. K. Saraswat MALCOLM ADISESHIAH Dr C.P. Chandrasekhar of Centre AWARD 2009 for Economic Studies and Planning, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. INDU SHARMA KATHA SAMMAN Mr Mohan Rana and Mr Bhagwan AWARD 2009 Dass Morwal PHALKE RATAN AWARD 2009 Actor Manoj Kumar SHANTI SWARUP BHATNAGAR Charusita Chakravarti – IIT Delhi, AWARDS 2008-2009 Santosh G. Honavar – L.V. Prasad Eye Institute; S.K. Satheesh –Indian Institute of Science; Amitabh Joshi and Bhaskar Shah – Biological Science; Giridhar Madras and Jayant Ramaswamy Harsita – Eengineering Science; R. Gopakumar and A. Dhar- Physical Science; Narayanswamy Jayraman – Chemical Science, and Verapally Suresh – Mathematical Science. NATIONAL MINORITY RIGHTS MM Tirmizi, advocate – Gujarat AWARD 2009 High Court 55th Filmfare Awards Best Actor (Male) Amitabh Bachchan–Paa; (Female) Vidya Balan–Paa Best Film 3 Idiots; Best Director Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots; Best Story Abhijat Joshi, Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Male) Boman Irani–3 Idiots; (Female) Kalki Koechlin–Dev D Best Screenplay Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra, Abhijat Joshi–3 Idiots; Best Choreography Bosco-Caesar–Chor Bazaari Love Aaj Kal Best Dialogue Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra–3 idiots Best Cinematography Rajeev Rai–Dev D Life- time Achievement Award Shashi Kapoor–Khayyam R D Burman Music Award Amit Tivedi. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents 01. INTERNATIONAL NEWS 02. NATIONAL NEWS 03. SPORTS 04. SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 05. OBITUARY 06. APPOINTMENTS AND RESIGNATIONS 07. IMPORTANT DAYS 08. SUMMITS AND MOU’S 09. AWARDS AND RECOGNITION 10. RANKING 11. BOOKS AND AUTHORS 12. BANKING AND ECONOMY 64, Kingsway Camp (Mall Road) Near GTB Nagar Metro Station. Gate No. 3 Delhi-9 1 Ph.: 011-45210004, 9555695557 INTERNATIONAL NEWS Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte resigns Italian Prime Minister, Giuseppe Conte resigned after losing his Senate majority, plunging the country into political uncertainty just as it’s battling the pandemic and a recession. He tendered his resignation to President Sergio Mattarella, the ultimate arbiter of Italian political crises, who invited him to stay on in a caretaker capacity pending discussions on what happens next. Italy was the first European country to face the full force of the Covid-19 pandemic and has since suffered badly, with the economy plunged into recession and deaths still rising by around 400 a day. Parts of the country remain under partial lockdown, the vaccination programme has slowed and a deadline is looming to agree on plans to spend billions of euros in European Union recovery funds. Kaja Kallas to become Estonia’s first female prime minister Kaja Kallas, the leader of the Reform Party will become Estonia’s first female prime minister. The Reform Party, led by Kallas, won the 2019 parliamentary election in Estonia with 34 MPs in the country’s 101-seat parliament, Riigikogu. Estonia would thus currently become the only country in the world where both the president Kersti Kaljulaid and the prime minister are women. -

Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2010 Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Nandrajog, Elaisha, "Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010)" (2010). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 219. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/219 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE HINDUTVA AND ANTI-MUSLIM COMMUNAL VIOLENCE IN INDIA UNDER THE BHARATIYA JANATA PARTY (1990-2010) SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR RODERIC CAMP AND PROFESSOR GASTÓN ESPINOSA AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY ELAISHA NANDRAJOG FOR SENIOR THESIS (Spring 2010) APRIL 26, 2010 2 CONTENTS Preface 02 List of Abbreviations 03 Timeline 04 Introduction 07 Chapter 1 13 Origins of Hindutva Chapter 2 41 Setting the Stage: Precursors to the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 3 60 Bharat : The India of the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 4 97 Mosque or Temple? The Babri Masjid-Ramjanmabhoomi Dispute Chapter 5 122 Modi and his Muslims: The Gujarat Carnage Chapter 6 151 Legalizing Communalism: Prevention of Terrorist Activities Act (2002) Conclusion 166 Appendix 180 Glossary 185 Bibliography 188 3 PREFACE This thesis assesses the manner in which India’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has emerged as the political face of Hindutva, or Hindu ethno-cultural nationalism. The insights of scholars like Christophe Jaffrelot, Ashish Nandy, Thomas Blom Hansen, Ram Puniyani, Badri Narayan, and Chetan Bhatt have been instrumental in furthering my understanding of the manifold elements of Hindutva ideology. -

Indresh Kumar Had Given All Co-Operation to the CBI : Dr. Vaidya by : INVC Team Published on : 12 Mar, 2011 12:51 AM IST

Indresh Kumar had given all co-operation to the CBI : Dr. Vaidya By : INVC Team Published On : 12 Mar, 2011 12:51 AM IST INVC,, Puttur, RSS national annual meet Akhil Bharatiya Pratinidhi Sabha (ABPS) was inaugurated today morning at Vivekananda College Premises, Puttur. Mohanji Bhagwat, Sarasanghachalak, lighted the traditional lamp as well as unfurled the coconut flower as part of the local tradition. Vedic chanting along with traditional panchavadyam were resounding the premises. Mr Suresh Joshi, Sarakaryavah was also present in Dias. Around 1400 delegates from across the country are participating in this 3-day annual meet. Office bearers of various organisations inspired by Sangh including VHP, Bharateeya Kisan Sangh which works among farmers, Vanavasi Kalyan Ashram – a tribal welfare organization; Akhil Bharateeya Vidyarthi Parishad – one of the biggest students’ organization in the country; Bharateeya Mazdoor Sangh – a leading trade union; Bharatiya Janata Party – one of the leading nationalistic political party of Bharat are in attendance. This apart, Office bearers of Vidhya Bharati, Vijnana Bharati, Kreeda Bharati, Seva Bharati, Samskrit Bharati, Samskar Bharati, Laghu Udyog Bharati as well as leaders from Rashtra Sevika Samithi, Swadeshi Jagaran Manch, Deendayal Samshodhan Samsthan, Bharat Vikas Parishad, Shaikshanika Mahasangh, Dharma Jagaran are also part of the conclave. Organizations which focuses on special issues like – Sakshama which works among the blind; Seema Suraksha Parishat – commitedly working among the people of border districts of our country in boosting their confidence, Poorva Sainik Parishat – working among the retired soldiers are also representing. All these organizations will present a report of their activities and their progress. State-wise activities of the RSS will also be reviewed. -

Hindi Theater Is Not Seen in Any Other Theatre

NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN DISCUSSION ON HINDI THEATRE FROM THE COLLECTIONS OF NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN AUDIO LIBRARY THE PRESENT SCENARIO OF HINDI THEATRE IN CALCUTTA ON th 15 May 1983 AT NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN PARTICIPANTS PRATIBHA AGRAWAL, SAMIK BANDYOPADHYAY, SHIV KUMAR JOSHI, SHYAMANAND JALAN, MANAMOHON THAKORE SHEO KUMAR JHUNJHUNWALA, SWRAN CHOWDHURY, TAPAS SEN, BIMAL LATH, GAYANWATI LATH, SURESH DUTT, PRAMOD SHROFF NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN EE 8, SECTOR 2, SALT LAKE, KOLKATA 91 MAIL : [email protected] Phone (033)23217667 1 NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN Pratibha Agrawal We are recording the discussion on “The present scenario of the Hindi Theatre in Calcutta”. The participants include – Kishen Kumar, Shymanand Jalan, Shiv Kumar Joshi, Shiv Kumar Jhunjhunwala, Manamohan Thakore1, Samik Banerjee, Dharani Ghosh, Usha Ganguly2 and Bimal Lath. We welcome all of you on behalf of Natya Shodh Sansthan. For quite some time we, the actors, directors, critics and the members of the audience have been appreciating and at the same time complaining about the plays that are being staged in Calcutta in the languages that are being practiced in Calcutta, be it in Hindi, English, Bangla or any other language. We felt that if we, the practitioners should sit down and talk about the various issues that are bothering us, we may be able to solve some of the problems and several issues may be resolved. Often it so happens that the artists take one side and the critics-audience occupies the other. There is a clear division – one group which creates and the other who criticizes. Many a time this proves to be useful and necessary as well. -

In Bad Faith? British Charity and Hindu Extremism

“I recognized two people pulling away my daughter Shabana. My daughter was screaming in pain asking the men to leave her alone. My mind was seething with fear and fury. I could do nothing to help my daughter from being assaulted sexually and tortured to death. My daughter was like a flower, still to see life.Why did they have to do this to her? What kind of men are these? The monsters tore my beloved daughter to pieces.” Medina Mustafa Ismail Sheikh, then in Kalol refugee camp, Panchmahals District, Gujarat This report is dedicated to the hundreds of thousands of Indians who have lost their homes, their loved ones or their lives because of the politics of hatred.We stand by those in India struggling for justice, and for a secular, democratic and tolerant future. 2 IN BAD FAITH? BRITISH CHARITY AND HINDU EXTREMISM INFORMATION FOR READERS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A separate report summary is available from Any final conclusions of fact or expressions of www.awaazsaw.org. Each section of this opinion are the responsibility of Awaaz – South report also begins with a summary of main Asia Watch Limited alone. Awaaz – South Asia findings. Watch would like to thank numerous individuals and organizations in the UK, India and the US for Section 1 provides brief information on advice and assistance in the preparation of this Hindutva and shows Sewa International UK’s report. Awaaz – South Asia Watch would also like connections with the RSS. Readers familiar to acknowledge the insights of the report The with these areas can skip to: Foreign Exchange of Hate researched by groups in the US. -

Sahitya Akademi PUNJABI Publications

Sahitya Akademi PUNJABI Publications MONOGRAPHS (MAKERS OF INDIAN LITERATURE) Amrita Pritam (Punjabi writer) By Sutinder Singh Noor Pp. 96, Rs. 40 First Edition: 2010 ISBN 978-81-260-2757-6 Amritlal Nagar (Hindi writer) By Shrilal Shukla Translated by Narinder Bhullar Pp. 116, First Edition: 1996 ISBN 81-260-0088-0 Rs. 15 Baba Farid (Punjabi saint-poet) By Balwant Singh Anand Translated by Prem Kotia Pp. 88, Reprint: 1995 Rs. 15 Balwant Gargi (Punjabi Playright) By Rawail Singh Pp. 88, Rs. 50 First Edition: 2013 ISBN: 978-81-260-4170-1 Bankim Chandra Chatterji (Bengali novelist) By S.C. Sengupta Translated by S. Soze Pp. 80, First Edition: 1985 Rs. 15 Banabhatta (Sanskrit poet) By K. Krishnamoorthy Translated by Prem Kotia Pp. 96, First Edition: 1987 Rs. 15 Bhagwaticharan Verma (Hindi writer) By Shrilal Shukla Translated by Baldev Singh ‘Baddan’ Pp. 96, First Edition: 1992 ISBN 81-7201-379-5 Rs. 15 Bhai Kahn Singh Nabha (Punjabi scholar and lexicographer) By Paramjeet Verma Pp. 136, Rs. 50.00 First Edition: 2017 ISBN: 978-93-86771-56-8 Bhai Vir Singh (Punjabi poet) By Harbans Singh Translated by S.S. Narula Pp. 112, Rs. 15 Second Edition: 1995 Bharatendu Harishchandra (Hindi writer) By Madan Gopal Translated by Kuldeep Singh Pp. 56, Rs. 15 First Edition: 1984 Bharati (Tamil writer) By Prema Nand kumar Translated by Pravesh Sharma Pp. 103, Rs.50 First Edition: 2014 ISBN: 978-81-260-4291-3 Bhavabhuti (Sanskrit poet) By G.K. Bhat Translated by Prem Kotia Pp. 80, Rs. 15 First Edition: 1983 Chandidas (Bengali poet) By Sukumar Sen Translated by Nirupama Kaur Pp. -

List of 253 Journalists Who Lost Their Lives Due to COVID-19. (Updated Until May 19, 2021)

List of 253 Journalists who lost their lives due to COVID-19. (Updated until May 19, 2021) Andhra Pradesh 1 Mr Srinivasa Rao Prajashakti Daily 2 Mr Surya Prakash Vikas Parvada 3 Mr M Parthasarathy CVR News Channel 4 Mr Narayanam Seshacharyulu Eenadu 5 Mr Chandrashekar Naidu NTV 6 Mr Ravindranath N Sandadi 7 Mr Gopi Yadav Tv9 Telugu 8 Mr P Tataiah -NA- 9 Mr Bhanu Prakash Rath Doordarshan 10 Mr Sumit Onka The Pioneer 11 Mr Gopi Sakshi Assam 12 Mr Golap Saikia All India Radio 13 Mr Jadu Chutia Moranhat Press club president 14 Mr Horen Borgohain Senior Journalist 15 Mr Shivacharan Kalita Senior Journalist 16 Mr Dhaneshwar Rabha Rural Reporter 17 Mr Ashim Dutta -NA- 18 Mr Aiyushman Dutta Freelance Bihar 19 Mr Krishna Mohan Sharma Times of India 20 Mr Ram Prakash Gupta Danik Jagran 21 Mr Arun Kumar Verma Prasar Bharti Chandigarh 22 Mr Davinder Pal Singh PTC News Chhattisgarh 23 Mr Pradeep Arya Journalist and Cartoonist 24 Mr Ganesh Tiwari Senior Journalist Delhi 25 Mr Kapil Datta Hindustan Times 26 Mr Yogesh Kumar Doordarshan 27 Mr Radhakrishna Muralidhar The Wire 28 Mr Ashish Yechury News Laundry 29 Mr Chanchal Pal Chauhan Times of India 30 Mr Manglesh Dabral Freelance 31 Mr Rajiv Katara Kadambini Magazine 32 Mr Vikas Sharma Republic Bharat 33 Mr Chandan Jaiswal Navodaya Times 34 Umashankar Sonthalia Fame India 35 Jarnail Singh Former Journalist 36 Sunil Jain Financial Express Page 1 of 6 Rate The Debate, Institute of Perception Studies H-10, Jangpura Extension, New Delhi – 110014 | www.ipsdelhi.org.in | [email protected] 37 Sudesh Vasudev -

Setting the Stage: a Materialist Semiotic Analysis Of

SETTING THE STAGE: A MATERIALIST SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF CONTEMPORARY BENGALI GROUP THEATRE FROM KOLKATA, INDIA by ARNAB BANERJI (Under the Direction of Farley Richmond) ABSTRACT This dissertation studies select performance examples from various group theatre companies in Kolkata, India during a fieldwork conducted in Kolkata between August 2012 and July 2013 using the materialist semiotic performance analysis. Research into Bengali group theatre has overlooked the effect of the conditions of production and reception on meaning making in theatre. Extant research focuses on the history of the group theatre, individuals, groups, and the socially conscious and political nature of this theatre. The unique nature of this theatre culture (or any other theatre culture) can only be understood fully if the conditions within which such theatre is produced and received studied along with the performance event itself. This dissertation is an attempt to fill this lacuna in Bengali group theatre scholarship. Materialist semiotic performance analysis serves as the theoretical framework for this study. The materialist semiotic performance analysis is a theoretical tool that examines the theatre event by locating it within definite material conditions of production and reception like organization, funding, training, availability of spaces and the public discourse on theatre. The data presented in this dissertation was gathered in Kolkata using: auto-ethnography, participant observation, sample survey, and archival research. The conditions of production and reception are each examined and presented in isolation followed by case studies. The case studies bring the elements studied in the preceding section together to demonstrate how they function together in a performance event. The studies represent the vast array of theatre in Kolkata and allow the findings from the second part of the dissertation to be tested across a variety of conditions of production and reception. -

Documentation Kerala

DDOOCCUUMMEENNTTAATTIIOONN KKEERRAALLAA An index to articles in journals/periodicals available in the Legislature Library Vol. 12 (3) July – September 2017 SECRETARIAT OF THE KERALA LEGISLATURE THIRUVANANTHAPURAM DOCUMENTATION KERALA An index to articles in journals/periodicals available in the Legislature Library Vol.12(3) July to September 2017 Compiled by G. Maryleela, Chief Librarian V. Lekha, Librarian G. Omanaseelan., Deputy Librarian Denny.M.X, Catalogue Assistant Type Setting Sindhu.B, Computer Assistant BapJw \nbak`m sse{_dnbn e`yamb {][m\s¸« B\pImenI {]kn²oIcW§fn h¶n-«pÅ teJ-\-§-fn \n¶pw kmamPnIÀ¡v {]tbmP\{]Zhpw ImenI {]m[m\yapÅXpambh sXc-sª-Sp¯v X¿m-dm-¡nb Hcp kqNnIbmWv ""tUm¡psatâj³ tIcf'' F¶ ss{Xamk {]kn²oIcWw. aebmf `mjbnepw Cw¥ojnepapÅ teJ\§fpsS kqNnI hnjbmSnØm\¯n c−v `mK§fmbn DÄs¸Sp¯nbn«p−v. Cw¥ojv A£camem {Ia¯n {]tXyI "hnjbkqNnI' aq¶mw `mK¯pw tNÀ¯n«p−v. \nbak`m kmamPnIÀ¡v hnhn[ hnjb§fn IqSp-X At\z-jWw \S-¯m³ Cu teJ\kqNnI klmbIcamIpsa¶v IcpXp¶p. Cu {]kn²oIcWs¯¡pdn¨pÅ kmamPnIcpsS A`n{]mb§fpw \nÀt±i§fpw kzm-KXw sN¿p¶p. hn.-sI. _m_p-{]-Imiv sk{I«dn tIcf \nbak`. CONTENTS Pages Malayalam Section 01-36 English Section 37-57 Index 58-82 PART I MALAYALAM Aadhaar 4. CS-Xp-]£w tZiob t\Xr-Xz-¯n- te¡v Db-c-Ww. ]n. IrjvW-{]-kmZv 1. B[mdpw kzIm-cy-Xbpw Nn´, 7 Pqsse 2017, t]Pv 12þ15 sk_m-Ìy³ t]mÄ ImÀjnI {]Xn-k-Ônbpw ImÀjnI hn¹-h- tZim-`n-am-\n, 30 Pqsse 2017, ¯nsâ {]m[m-\yhpw hnh-cn-¡p¶ teJ-\w. -

Jupiter Institute Current Affairs March 2019 E.Pdf

Jupiter Institute Current Affairs - March 2019 Table of Contents Current Affairs: Important Days ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Current Affairs: Appointments ......................................................................................................................................... 2 International Appointments: ........................................................................................................................................ 2 National Appointments: ............................................................................................................................................... 2 Current Affairs: Awards and Honours ............................................................................................................................... 3 Current Affairs: Banking and Finance ............................................................................................................................... 4 Current Affairs: Defence .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Current Affairs: Economic Affairs ..................................................................................................................................... 8 Current Affairs: International ..........................................................................................................................................11 -

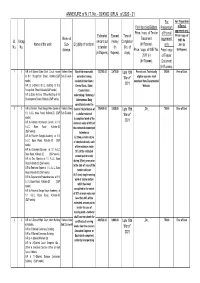

02/KWD /OFLN of 2020 - 21 for for Preparation for Intending Bidders Preparation of Formal Aggrement Only

ANNEXURE of N.I.T. No. - 02/KWD /OFLN of 2020 - 21 For For Preparation For Intending Bidders Preparation of Formal aggrement only. Price / copy of Tender of Formal Estimated Earnest Time of Price / copy of Name of Document aggrement Sl. Group amount put money Completion WBF No. Name of the work Sub- Eligibility of tenderer. (In Rupees). only 2911 (ii) No. No. to tender (In (No. of division. Price / copy of WBF No. Price / copy (In Rupees). (In Rupees). Rupees). days). 2911 (ii) of Tender (In Rupees). Document (In Rupees). 1 1 A/R to 5-Storied State Govt. Circuit House Kolkata West Bonafied resourceful 123,760.00 2,475.00 Upto 15th Free of cost. Technically 250.00 Free of Cost at 9/1, Hungerford Street, Kolkata.(S&P Sub Division-I outsiders having 'March" eligible agencies shall works) credential from State / download from Departmental 2021 A/R to 3-Storied D.I.G. Building at 9/1, Central Govt., State / Website. Hungerford Street, Kolkata(S&P works) Central Govt. A/R to State Archive Office Building at 43, undertaking / Statutory / Shakespeare Sarani, Kolkata.(S&P works) Autonomous Body constituted under the 2 2 A/R to Nandan, West Bengal Flim Centre at Kolkata West Central / State Statute of 176,400.00 3,528.00 Upto 15th _Do_ 750.00 Free of Cost 1/1, A.J.C. bose Road, Kolkata-20. (S&P Sub Division-I a similar nature of 'March" works) i) completed work of the 2021 A/R to Kolkata Information Centre at 1/1, minimum value of 40% of A.J.C.