INT856 Advocating for Abolition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

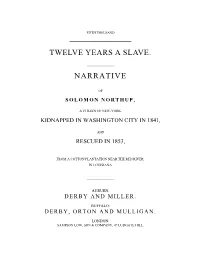

Twelve Years a Slave. Narrative

FIFTH THOUSAND TWELVE YEARS A SLAVE. NARRATIVE OF SOLOMON NORTHUP, A CITIZEN OF NEW-YORK, KIDNAPPED IN WASHINGTON CITY IN 1841, AND RESCUED IN 1853, FROM A COTTON PLANTATION NEAR THE RED RIVER, IN LOUISIANA. AUBURN: DERBY AND MILLER. BUFFALO: DERBY, ORTON AND MULLIGAN. LONDON: SAMPSON LOW, SON & COMPANY, 47 LUDGATE HILL. 1853. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year one thousand eight hundred and fifty-three, by D E R B Y A N D M ILLER , In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the Northern District of New-York. ENTERED IN LONDON AT STATIONERS' HALL. TO HARRIET BEECHER STOWE: WHOSE NAME, THROUGHOUT THE WORLD, IS IDENTIFIED WITH THE GREAT REFORM: THIS NARRATIVE, AFFORDING ANOTHER Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin, IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED "Such dupes are men to custom, and so prone To reverence what is ancient, and can plead A course of long observance for its use, That even servitude, the worst of ills, Because delivered down from sire to son, Is kept and guarded as a sacred thing. But is it fit, or can it bear the shock Of rational discussion, that a man Compounded and made up, like other men, Of elements tumultuous, in whom lust And folly in as ample measure meet, As in the bosom of the slave he rules, Should be a despot absolute, and boast Himself the only freeman of his land?" Cowper. [Pg vii] CONTENTS. PAGE. EDITOR'S PREFACE, 15 CHAPTER I. Introductory—Ancestry—The Northup Family—Birth and Parentage—Mintus Northup—Marriage with Anne Hampton—Good Resolutions—Champlain Canal—Rafting Excursion to Canada— Farming—The Violin—Cooking—Removal to Saratoga—Parker and Perry—Slaves and Slavery— The Children—The Beginning of Sorrow, 17 CHAPTER II. -

Frederick Douglass

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection AMERICAN CRISIS BIOGRAPHIES Edited by Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer, Ph. D. Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Zbe Hmcrican Crisis Biographies Edited by Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer, Ph.D. With the counsel and advice of Professor John B. McMaster, of the University of Pennsylvania. Each I2mo, cloth, with frontispiece portrait. Price $1.25 net; by mail» $i-37- These biographies will constitute a complete and comprehensive history of the great American sectional struggle in the form of readable and authoritative biography. The editor has enlisted the co-operation of many competent writers, as will be noted from the list given below. An interesting feature of the undertaking is that the series is to be im- partial, Southern writers having been assigned to Southern subjects and Northern writers to Northern subjects, but all will belong to the younger generation of writers, thus assuring freedom from any suspicion of war- time prejudice. The Civil War will not be treated as a rebellion, but as the great event in the history of our nation, which, after forty years, it is now clearly recognized to have been. Now ready: Abraham Lincoln. By ELLIS PAXSON OBERHOLTZER. Thomas H. Benton. By JOSEPH M. ROGERS. David G. Farragut. By JOHN R. SPEARS. William T. Sherman. By EDWARD ROBINS. Frederick Douglass. By BOOKER T. WASHINGTON. Judah P. Benjamin. By FIERCE BUTLER. In preparation: John C. Calhoun. By GAILLARD HUNT. Daniel Webster. By PROF. C. H. VAN TYNE. Alexander H. Stephens. BY LOUIS PENDLETON. John Quincy Adams. -

Can Words Lead to War?

Middle School Uncle Tom’s Cabin Inquiry Can Words Lead to War? Full-page illustration from first edition Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Hammatt Billings. Available in Uncle Tom’s Cabin & American Culture. Supporting Questions 1. How did Harriet Beecher Stowe describe slavery in Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 2. What led Harriet Beecher Stowe to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 3. How did northerners and southerners react to Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 4. How did Uncle Tom’s Cabin affect abolitionism? THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION- NONCOMMERCIAL- SHAREALIKE 4.0 INTERNATIONAL LICENSE. 1 Middle School Uncle Tom’s Cabin Inquiry Can Words Lead to War? Framework for Summary Objective 12: Students will understand the growth of the abolitionist movement in the Teaching American 1830s and the Southern view of the movement as a physical, economic and political threat. Slavery Consider the power of words and examine a video of students using words to try to bring about Staging the Question positive change. Supporting Question 1 Supporting Question 2 Supporting Question 3 Supporting Question 4 How did Harriet Beecher What led Harriet Beecher How did people in the How did Uncle Tom’s Stowe describe slavery in Stowe to write Uncle North and South react to Cabin affect abolitionism? Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Tom’s Cabin? Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Formative Formative Formative Formative Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Complete a source analysis List four quotes from the Make a T-chart comparing Participate in a structured chart to write a summary sources that point to the viewpoints expressed discussion regarding the of Uncle Tom’s Cabin that Stowe’s motivation and in northern and southern impact Uncle Tom’s Cabin includes main ideas and write a paragraph newspaper reviews of had on abolitionism. -

Abolitionist Movement

Abolitionist Movement The goal of the abolitionist movement was the immediate emancipation of all slaves and the end of racial discrimination and segregation. Advocating for immediate emancipation distinguished abolitionists from more moderate anti-slavery advocates who argued for gradual emancipation, and from free-soil activists who sought to restrict slavery to existing areas and prevent its spread further west. Radical abolitionism was partly fueled by the religious fervor of the Second Great Awakening, which prompted many people to advocate for emancipation on religious grounds. Abolitionist ideas became increasingly prominent in Northern churches and politics beginning in the 1830s, which contributed to the regional animosity between North and South leading up to the Civil War. The Underground Railroad c.1780 - 1862 The Underground Railroad, a vast network of people who helped fugitive slaves escape to the North and to Canada, was not run by any single organization or person. Rather, it consisted of many individuals -- many whites but predominantly black -- who knew only of the local efforts to aid fugitives and not of the overall operation. Still, it effectively moved hundreds of slaves northward each year -- according to one estimate, the South lost 100,000 slaves between 1810 and 1850. Still, only a small percentage of escaping slaves received assistance from the Underground Railroad. An organized system to assist runaway slaves seems to have begun towards the end of the 18th century. In 1786 George Washington complained about how one of his runaway slaves was helped by a "society of Quakers, formed for such purposes." The system grew, and around 1831 it was dubbed "The Underground Railroad," after the then emerging steam railroads. -

Theodore Parker's Man-Making Strategy: a Study of His Professional Ministry in Selected Sermons

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1993 Theodore Parker's Man-Making Strategy: A Study of His Professional Ministry in Selected Sermons John Patrick Fitzgibbons Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Fitzgibbons, John Patrick, "Theodore Parker's Man-Making Strategy: A Study of His Professional Ministry in Selected Sermons" (1993). Dissertations. 3283. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3283 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1993 John Patrick Fitzgibbons Theodore Parker's Man-Making Strategy: A Study of His Professional Ministry in Selected Sermons by John Patrick Fitzgibbons, S.J. A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Chicago, Illinois May, 1993 Copyright, '°1993, John Patrick Fitzgibbons, S.J. All rights reserved. PREFACE Theodore Parker (1810-1860) fashioned a strategy of "man-making" and an ideology of manhood in response to the marginalization of the professional ministry in general and his own ministry in particular. Much has been written about Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) and his abandonment of the professional ministry for a literary career after 1832. Little, however, has been written about Parker's deliberate choice to remain in the ministry despite formidable opposition from within the ranks of Boston's liberal clergy. -

The Slave's Cause: a History of Abolition

Civil War Book Review Summer 2016 Article 5 The Slave's Cause: A History of Abolition Corey M. Brooks Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr Recommended Citation Brooks, Corey M. (2016) "The Slave's Cause: A History of Abolition," Civil War Book Review: Vol. 18 : Iss. 3 . DOI: 10.31390/cwbr.18.3.06 Available at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr/vol18/iss3/5 Brooks: The Slave's Cause: A History of Abolition Review Brooks, Corey M. Summer 2016 Sinha, Manisha The Slave's Cause: A History of Abolition. Yale University Press, $37.50 ISBN 9780300181371 The New Essential History of American Abolitionism Manisha Sinha’s The Slave’s Cause is ambitious in size, scope, and argument. Covering the entirety of American abolitionist history from the colonial era through the Civil War, Sinha, Professor of Afro-American Studies at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, presents copious original research and thoughtfully and thoroughly mines the substantial body of recent abolitionist scholarship. In the process, Sinha makes a series of potent, carefully intertwined arguments that stress the radical and interracial dimensions and long-term continuities of the American abolitionist project. The Slave’s Cause portrays American abolitionists as radical defenders of democracy against countervailing pressures imposed both by racism and by the underside of capitalist political economy. Sinha goes out of her way to repudiate outmoded views of abolitionists as tactically unsophisticated utopians, overly sentimental romantics, or bourgeois apologists subconsciously rationalizing the emergent capitalism of Anglo-American “free labor" society. In positioning her work against these interpretations, Sinha may somewhat exaggerate the staying power of that older historiography, as most (though surely not all) current scholars in the field would likely concur wholeheartedly with Sinha’s valorization of abolitionists as freedom fighters who achieved great change against great odds. -

The PAS and American Abolitionism: a Century of Activism from the American Revolutionary Era to the Civil War

The PAS and American Abolitionism: A Century of Activism from the American Revolutionary Era to the Civil War By Richard S. Newman, Associate Professor of History Rochester Institute of Technology The Pennsylvania Abolition Society was the world's most famous antislavery group during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Indeed, although not as memorable as many later abolitionists (from William Lloyd Garrison and Lydia Maria Child to Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth), Pennsylvania reformers defined the antislavery movement for an entire generation of activists in the United States, Europe, and even the Caribbean. If you were an enlightened citizen of the Atlantic world following the American Revolution, then you probably knew about the PAS. Benjamin Franklin, a former slaveholder himself, briefly served as the organization's president. French philosophes corresponded with the organization, as did members of John Adams’ presidential Cabinet. British reformers like Granville Sharp reveled in their association with the PAS. It was, Sharp told told the group, an "honor" to be a corresponding member of so distinguished an organization.1 Though no supporter of the formal abolitionist movement, America’s “first man” George Washington certainly knew of the PAS's prowess, having lived for several years in the nation's temporary capital of Philadelphia during the 1790s. So concerned was the inaugural President with abolitionist agitation that Washington even shuttled a group of nine slaves back and forth between the Quaker State and his Mount Vernon home (still, two of his slaves escaped). The PAS was indeed a powerful abolitionist organization. PAS Origins The roots of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society date to 1775, when a group of mostly Quaker men met at a Philadelphia tavern to discuss antislavery measures. -

Harriet Jacobs's Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl; a Literary Weapon

PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ALGERIA Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research University of Tlemcen Faculty of Letters and Languages Department of English Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl; a Literary Weapon Against Slavery Dissertation submitted to the Department of English as a partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Literature and Civilization Presented by Supervised by Ms.Tasnim BELAIDOUNI Ms.Meriem MENGOUCHI BOARD OF EXAMINERS Dr. Wassila MOURO Chairwoman Ms. Meriem MENGOUCHI Supervisor Dr. Frid DAOUDI Examiner Academic Year: 2016/2017 Dedications To those who believed in me To those who helped me through hard times To my Mother, my family and my friends I dedicate this work ii Acknowledgements Immense loads of gratitude and thanks are addressed to my teacher and supervisor Ms. Meriem MENGOUCHI; this work could have never come to existence without your vivacious guidance, constant encouragement, and priceless advice and patience. My sincerest acknowledgements go to the board of examiners namely; Dr. Wassila MOURO and Dr. Frid DAOUDI My deep gratitude to all my teachers iii Abstract Harriet Ann Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl seemed not to be the only literary work which tackled the issue of woman in slavery. However, this autobiography is the first published slave narrative written in the nineteenth century. In fact, the primary purpose of this research is to dive into Incidents in order to examine the author’s portrayal of a black female slave fighting for her freedom and her rights. On the other hand, Jacobs shows that despite the oppression and the persecution of an enslaved woman, she did not remain silent, but she strived to assert herself. -

Stewart Dissertation 20126.Pdf

Copyright by Anna Rebecca Stewart 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Anna Rebecca Stewart certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Beyond Obsolescence: The Reconstruction of Abolitionist Texts Committee: Coleman Hutchison, Co-Supervisor Michael Winship, Co-Supervisor Evan Carton Gretchen Murphy Jacqueline Jones Beyond Obsolescence: The Reconstruction of Abolitionist Texts by Anna Rebecca Stewart, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2012 Dedication For Sam, with love and gratitude. Acknowledgements As an avid reader of acknowledgements sections, I am always curious about the conversations that sparked and enlivened projects as well as the relationships that sustained their writers. As I turn to write my own for this dissertation project, I realize just how impossible it is to sum up those intellectual and personal debts—the many kindnesses, questions, and encouragements that have helped me navigate this dissertation process and my own development as a thinker and writer. Coleman Hutchison and Michael Winship have been staunch supporters and careful readers, modeling the kind of mentor-teacher-scholars that we all aspire to be but can often only hope to become through the gift of such examples. Early in my graduate school career, Michael taught me a valuable lesson about not committing to projects, even short semester papers, that did not capture my imagination and interest. Our conversations kept me engaged and deep in the archive, where my project first began to take shape and where I found my footing as a researcher. -

American Liberal Pacifists and the Memory of Abolitionism, 1914-1933 Joseph Kip Kosek

American Liberal Pacifists and the Memory of Abolitionism, 1914-1933 Joseph Kip Kosek Americans’ memory of their Civil War has always been more than idle reminiscence. David Blight’s Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory is the best new work to examine the way that the nation actively reimagined the past in order to explain and justify the present. Interdisciplinary in its methods, ecumenical in its sources, and nuanced in its interpretations, Race and Reunion explains how the recollection of the Civil War became a case of race versus reunion in the half-century after Gettysburg. On one hand, Frederick Douglass and his allies promoted an “emancipationist” vision that drew attention to the role of slavery in the conflict and that highlighted the continuing problem of racial inequality. Opposed to this stance was the “reconciliationist” ideal, which located the meaning of the war in notions of abstract heroism and devotion by North and South alike, divorced from any particular allegiance. On this ground the former combatants could meet undisturbed by the problems of politics and ideological difference. This latter view became the dominant memory, and, involving as it did a kind of forgetting, laid the groundwork for decades of racial violence and segregation, Blight argues. Thus did memory frame the possibilities of politics and moral action. The first photograph in Race and Reunion illustrates this victory of reunion, showing Woodrow Wilson at Gettysburg in 1913. Wilson, surrounded by white veterans from North and South, with Union and Confederate flags flying, is making a speech in which he praises the heroism of the combatants in the Civil War while declaring their “quarrel forgotten.” The last photograph in Blight’s book, though, invokes a different story about Civil War memory. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 I I 75-3032

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

1900. Frank P

ANNUAL REPORTS OF THE OFFICERS OF THE TOWN OF BEDFORD, FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR EN DING FEBRUARY 1, 1901. BOSTON : R. H. BLODGETT & CO. Printers 30 Bromfield Street 1901 3 TOWN OFFICERS 1900-1901. School Committee. ERN BST H . Hos lilER, Term exp ires 1903. G. I ,001,11s, Term expires Selectmen. ELIHU 1902. MRS. M ARY E. LAWS, Term expires 1901. EDW1-N H . BLA KE. T erm expires 1903- . FREDERlC P ARKER, T erm expires 1902 . 1901 Trusues of the Bedford Free Public Library. A llTHUll H. P ARKER, T erm expires • G EORGE R. BLINN, Term expires 190'1. A BR.l. ld E . BROWN, Term expires 1903. Fence Viewers. ARTHUR H. P ARKER- ELIHU G . LoOMIS, Term expires 1902. FREDElllC PARKER. EDWIN H. BLAKE. CHARLES w. JENKS, Term expires 1901. .Assessors. A ls o the a cting pastors of the th ree churches, together with the chairman of Board of Select men a nd chairman of t he School C ommittee. "ILLIAM G . HARTWBLL, T erm expires 1903- . ""'2 \,, L. H oDGOON Term expires lvv, · IRVI NG • G L NE T erm expires 1001. Shawsheen Cemetery Commitue. WILLIS · A • G EORGE R. BLINN, T erm expires 1903. Ocerseer~ of Poor. C HARLES w. JENKS, Term expires 1901. A BRAM E. BROWN, T erm expires 1902. HARTWELL, Term expires 1903- . l90'l B H umns Term ex pires · \.V ILLIAM . ' \" SPREDBY T erm expires l 901 . Constables. J AM ES ••· ' E DWARD WALSH. J OSEPH ll. MCFARLAND. QUINCY S. COLE. Town Clerk and TreaBUrer. Funeral Undertaker. • C W..llLES A.