After the Boom: Thematic Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry

LAO PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC PEACE INDEPENDENCE DEMOCRATIC UNITY PROSPERITY Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry POVERTY REDUCTION FUND PHASE III ANNUAL PROGRESS REPORT (January – December 2019) Suspended bridge, Luangphakham to Nongkham village, Long district, Luangnamtha province (January 2020) Nahaidiao Rd, P.O.Box 4625, Vientiane, Lao PRF Tel: (+856) 21 261479 -80 Fax: (+856) 21 261481, Website: www.prflaos.org January 2018 ABBREVIATIONS AWPB Annual Work Plan and Budget AFN Agriculture for Nutrition CD Community Development CDD Community Driven Development CF Community Facilitator CFA Community Force Account CLTS Community-Lead Total Sanitation DAFO District Agriculture and Forestry Office Deepen CDD Deepen Community Driven Development DPO District Planning Office DRM Disaster Risks Management DSEDP District Social Economic Development Plan EM Energy and Mine FRM Feedback and Resolution Mechanism FNG Farmer Nutrition Group GESI Gender Equity and Social Inclusion GOL Government of Lao GIS Geography information system GPAR Governance Public Administration Reform HH Household(s) HR Human Resource IE Internal Evaluation IEC Information, Education, Communication IGA Income Generating Activities IFAD International Fund for Agriculture Development IFR Interim Un-Audited Financial Report KBF Kum Ban Facilitator KDPs Kum Ban Development Plans KPIs Key Performance Indicators LAK Lao Kip (Lao Currency) LN Livelihood and Nutrition LWU Lao Women Union LYU Lao Youth Union M&E Monitoring and Evaluation MIS Management information system MNS Minutes -

Monograph of Cercosporoid Fungi from Laos

Current Research in Environmental & Applied Mycology Doi 10.5943/cream/3/1/2 Monograph of Cercosporoid fungi from Laos Phengsintham P1,2, Chukeatirote E 1, McKenzie EHC3, Hyde KD1 and Braun U4 1School of Science, Mae Fah Luang University, Chiang Rai 57100, Thailand 2Biology Department, Faculty of Sciences, National University of Laos 3Landcare Research, Private Bag 92170, Auckland, New Zealand 4Martin-Luther-Universität, Institut für Biologie, Bereich Geobotanik und Botanischer Garten, Herbarium, Neuwerk 21 06099 Halle/S. Germany Phengsintham P, Chukeatirote E, McKenzie EHC, Hyde KD, Braun U 2013 – Monograph of Cercosporoid fungi from Laos. Current Research in Environmental & Applied Mycology 3(1), 34– 158, doi 10.5943/cream/3/1/2 The Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Lao PDR) or Laos is a landlocked country. During a study of cercosporoid fungi in Laos, 113 species were identified including 108 species of true cercosporoid fungi; Cercospora (41 species), Passalora (10), Pseudocercospora (49), and Zasmidium (8). Five species of morphological similar fungi we also found; Cladosporium (1 species), Periconiella (1), Pseudocercosporella (1), Scolecostigmina (1), and Spiropes (1). Sixteen new taxa were established namely, Cercospora duranticola, C. senecionis-walkeri, Passalora dipterocarpi, P. helicteris-viscidae, Pseudocercospora getoniae, P. mannanorensis var. paucifasciculata, P. micromeli, P. tectoniae, P. wenlandiphila, Zasmidium aporosae, Z. dalbergiae, Z. jasminicola, Z. meynae-laxiflorae, Z. micromeli, Z. suregadae, Z. pavettae. Eighty-seven species are described in full and illustrated, and another 26 species are only listed since they have been previously recorded from Laos. Key words – Asia – Cercospora – Cercosporoid fungus – monograph Article Information Received 29 January 2013 Accepted 20 March 2013 Published online 25 June 2013 *Corresponding author: Kevin D. -

Ethnic Group Development Plan LAO: Northern Rural Infrastructure

Ethnic Group Development Plan Project Number: 42203 May 2016 LAO: Northern Rural Infrastructure Development Sector Project - Additional Financing Prepared by Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry for the Asian Development Bank. This ethnic group development plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Ethnic Group Development Plan Nam Beng Irrigation Subproject Tai Lue Village, Lao PDR TABLE OF CONTENTS Topics Page LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND TERMS v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A10-1 A. Introduction A10-1 B. The Nam Beng Irrigation Subproject A10-1 C. Ethnic Groups in the Subproject Areas A10-2 D. Socio-Economic Status A10-2 a. Land Issues A10-3 b. Language Issues A10-3 c. Gender Issues A10-3 d. Social Health Issues A10-4 E. Potential Benefits and Negative Impacts of the Subproject A10-4 F. Consultation and Disclosure A10-5 G. Monitoring A10-5 1. BACKGROUND INFORMATION A10-6 1.1 Objectives of the Ethnic Groups Development Plan A10-6 1.2 The Northern Rural Infrastructure Development Sector Project A10-6 (NRIDSP) 1.3 The Nam Beng Irrigation Subproject A10-6 2. -

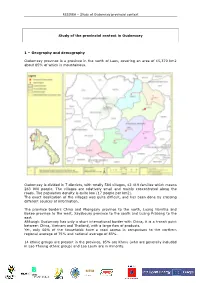

Study of the Provincial Context in Oudomxay 1

RESIREA – Study of Oudomxay provincial context Study of the provincial context in Oudomxay 1 – Geography and demography Oudomxay province is a province in the north of Laos, covering an area of 15,370 km2 about 85% of which is mountainous. Oudomxay is divided in 7 districts, with totally 584 villages, 42 419 families which means 263 000 people. The villages are relatively small and mainly concentrated along the roads. The population density is quite low (17 people per km2). The exact localization of the villages was quite difficult, and has been done by crossing different sources of information. The province borders China and Phongsaly province to the north, Luang Namtha and Bokeo province to the west, Xayaboury province to the south and Luang Prabang to the east. Although Oudomxay has only a short international border with China, it is a transit point between China, Vietnam and Thailand, with a large flow of products. Yet, only 66% of the households have a road access in comparison to the northern regional average of 75% and national average of 83%. 14 ethnic groups are present in the province, 85% are Khmu (who are generally included in Lao Theung ethnic group) and Lao Loum are in minority. MEM Lao PDR RESIREA – Study of Oudomxay provincial context 2- Agriculture and local development The main agricultural crop practiced in Oudomxay provinces is corn, especially located in Houn district. Oudomxay is the second province in terms of corn production: 84 900 tons in 2006, for an area of 20 935 ha. These figures have increased a lot within the last few years. -

Project Title: Country: Accredited Entity: Date of First Submission

Implementation of the Lao PDR Emission Reductions Programme Project Title: through improved governance and sustainable forest landscape management (Project 1) Country: Lao People’s Democratic Republic Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) Accredited Entity: GmbH Date of first submission: 2019/03/02 Date of current submission: 2019/10/11 Version number: V.011 GREEN CLIMATE FUND FUNDING PROPOSAL V.2.0 | PAGE 0 OF 95 Contents Section A PROJECT / PROGRAMME SUMMARY Section B PROJECT INFORMATION Section C FINANCING INFORMATION Section D EXPECTED PERFORMANCE AGAINST INVESTMENT CRITERIA Section E LOGICAL FRAMEWORK Section F RISK ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT Section G GCF POLICIES AND STANDARDS Section H ANNEXES Note to Accredited Entities on the use of the funding proposal template • Accredited Entities should provide summary information in the proposal with cross- reference to annexes such as feasibility studies, gender action plan, term sheet, etc. • Accredited Entities should ensure that annexes provided are consistent with the details provided in the funding proposal. Updates to the funding proposal and/or annexes must be reflected in all relevant documents. • The total number of pages for the funding proposal (excluding annexes) should not exceed 60. Proposals exceeding the prescribed length will not be assessed within the usual service standard time. • The recommended font is Arial, size 11. • Under the GCF Information Disclosure Policy, project and programme funding proposals will be disclosed on the GCF website, simultaneous with the submission to the Board, subject to the redaction of any information that may not be disclosed pursuant to the IDP. Accredited Entities are asked to fill out information on disclosure in section G.4. -

8Th FIVE-YEAR NATIONAL SOCIO- ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN

Lao People’s Democratic Republic Peace Independence Unity Prosperity 8th FIVE-YEAR NATIONAL SOCIO- ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN (2016–2020) (Officially approved at the VIIIth National Assembly’s Inaugural Session, 20–23 April 2016, Vientiane) Ministry of Planning and Investment June 2016 8th FIVE-YEAR NATIONAL SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN (2016–2020) (Officially approved at the VIIIth National Assembly’s Inaugural Session, 20–23 April 2016, Vientiane) Ministry of Planning and Investment June 2016 FOREWORD The 8th Five-Year National Socio-economic Development Plan (2016–2020) “8th NSEDP” is a mean to implement the resolutions of the 10th Party Conference that also emphasizes the areas from the previous plan implementation that still need to be achieved. The Plan also reflects the Socio-economic Development Strategy until 2025 and Vision 2030 with an aim to build a new foundation for graduating from LDC status by 2020 to become an upper-middle-income country by 2030. Therefore, the 8th NSEDP is an important tool central to the assurance of the national defence and development of the party’s new directions. Furthermore, the 8th NSEDP is a result of the Government’s breakthrough in mindset. It is an outcome- based plan that resulted from close research and, thus, it is constructed with the clear development outcomes and outputs corresponding to the sector and provincial development plans that should be able to ensure harmonization in the Plan performance within provided sources of funding, including a government budget, grants and loans, -

Northern Rural Infrastructure Development Sector Project – Additional Financing

Environmental and Social Monitoring Report 5th Semi-Annual Environmental and Social Monitoring Report January - June 2020 December 2020 Lao PDR: Northern Rural Infrastructure Development Sector Project – Additional Financing Prepared by the National Project Management Office of Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry for the Government of Lao PDR and the Asian Development Bank. 1 NOTE (i) In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This environmental and social monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. 2 GRANT No. 0534-LAO LAO PDR Safeguards Monitoring Report 5th Semi-Annual Safeguards Monitoring Report January – June 2020 Lao Peoples Democratic Republic: Northern Rural Infrastructure Development Sector Project Additional Financing Prepared by the National Project Management Office (NPMO)/ Grant Implementation Consultants (GIC), Department of Planning and Finance, Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry for the Government of Lao PDR and the Asian Development Bank. NOTE In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This safeguards monitoring report is a document of the grant recipient. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

Data Collection Survey on Education Environment of Lower Secondary Schools in Lao P.D.R

Final Report: Data Collection Survey on Education Environment of Lower Secondary Schools in Lao P.D.R February, 2016 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Mohri, Architect and Associates, Inc. 1R JR 16-04 Final Report: Data Collection Survey on Education Environment of Lower Secondary Schools in Lao P.D.R February, 2016 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Mohri, Architect and Associates, Inc. Contents Chapter 1 SUMMARY OF STUDY ............................................................................................. 1-1 1-1 Context of Study .............................................................................................................. 1-1 1-2 Objective of Study ........................................................................................................... 1-1 1-3 Timeframe of Study ......................................................................................................... 1-1 1-4 Members of Study Mission (Name, Responsibility, Organization belonging to) ...... 1-2 1-5 Concerned persons consulted and/or interviewed ......................................................... 1-2 1-6 Contents of Study .......................................................................................................... 1-2 1-6-1 Local Study I ............................................................................................................ 1-2 1-6-2 Local Study II ........................................................................................................... 1-3 CHAPTER -

Institutional Strengthening for Poverty Monitoring and Evaluation

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 35473 2008 Lao PDR: Institutional Strengthening for Poverty Monitoring and Evaluation {(Financed by the <source of funding>)} Prepared by {author(s)} {Firm name} {City, country} For {Executing agency} {Implementing agency} This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. (For project preparatory technical assistance: All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. Participatory Poverty Assessment (2006) Lao People’s Democratic Republic National Statistics Center Asian Development Bank James R. Chamberlain ADB TA 4521 Institutional Strengthening for Poverty Monitoring and Evaluation 2006-2007 Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report National Statistics Center All Rights Reserved This report was prepared by consultants based on results of the technical assistance project Institutional Strengthening for Poverty Monitoring and Evaluation funded by the Asian Development Bank. 3 Figure 1 - Map of the Lao PDR 4 Table of Contents FOREWORD..............................................................................................................................................8 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS......................................................................................................................9 ABBREVIATIONS..................................................................................................................................10 -

Subproject Field Survey – Final Report

Subproject Field Survey – Final Report Project Number: TA 8882 17 December 2015 Lao People’s Democratic Republic: Northern Rural Infrastructure Development Sector Project – Due Diligence for Additional Financing Prepared by Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, Department of Planning and Cooperation Additional Financing of Northern Rural Infrastructure Development Sector Project (RRP LA 42203) ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank DAFO – District Agriculture and Forestry Office GIC – Grant Implementation Consultant (on-going NRI project) GOL – Government of Lao PDR GPS – Global Positioning System HHs – households LMC – Left Main Canal MC – Main Canal NCA – NPMO – National Project Management Office NRI – the on-going Northern Rural Infrastructure Sector Project NRI-AF – NR1A – NR2W – NR3 – O&M – operation and maintenance PAFO – Provincial Agriculture and Forestry Office RC – reinforced concrete RMC – Right Main Canal S-PPTA – small-scale project preparation technical assistance WUG – water user group WEIGHTS AND MEASURES ha – hectare Kip/day – Kip/ha – km – kilometer m – meter m3 – cubic meter m3/sec – cubic meter per second t/ha – Yuan/kg – NOTE In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. Additional Financing of Northern Rural Infrastructure Development Sector Project (RRP LAO 42203) CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 A. Introduction 1 B. Longlist of Candidate Subprojects 1 C. Eligibility Criteria 1 D. Desktop Review Preliminary Findings 2 II. OUTLINE OF SUBPROJECT FIELD SURVEY 3 A. Objective of the Field Survey 3 B. Methodology 4 III. FINDINGS 5 A. Key Issues 5 B. Other Findings/Observations 8 C. Subproject Assessment and Prioritization 10 IV. CONCLUSIONS 10 Annexes Annex A. Subproject Location Map 12 Annex B. Eligibility Criteria 13 Annex C. -

Rubber Plantation Expansion Related Land Use Change Along the Laos-China Border Region

sustainability Article Rubber Plantation Expansion Related Land Use Change along the Laos-China Border Region Xiaona Liu 1, Luguang Jiang 2, Zhiming Feng 2,* and Peng Li 2 1 Research & Development Center for Grass and Environment, Beijing Academy of Agricultural and Forestry Sciences, Beijing 100097, China; [email protected] 2 Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; [email protected] (L.J.); [email protected] (P.L.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-10-6488-9393 Academic Editor: Vincenzo Torretta Received: 16 June 2016; Accepted: 27 September 2016; Published: 11 October 2016 Abstract: Spatial-temporal changes of land use and land cover in Luang Namtha Province in northern part of Laos was analyzed using Landsat TM (Thematic Mapper)/ETM+ (Enhanced Thematic Mapper) images from 1990 to 2010 since the opening of the Boten border adjacent to China. The results showed that: (1) “forest land—cultivated land—grassland” was the primary landscape structure. Woodland was the major land cover type, while paddy field was the dominant land use type replaced by rubber plantation in 2010; (2) since the opening of the border crossings in 1994, the rate and intensity of land use change were accelerated and enhanced gradually, especially in the recent decade. Woodland decreased significantly, while shrubland, rubber plantation and swidden land increased obviously. Rubber plantation and swidden land showed the fastest growth derived from woodland and shrubland, indicating continuous human activities and slash-and-burn farming; and (3) during 1990–2010, swidden land was mainly located in northern mountainous areas with frequently increased changing spatial distribution in the recent decade. -

Thammasat Institute of Area Studies (TIARA), Thammasat University

No. 06/ 2017 Thammasat Institute of Area Studies WORKING PAPER SERIES 2017 Regional Distribution of Foreign Investment in Lao PDR Chanthida Ratanavong December, 2017 THAMMASAT UNIVERSITY PAPER NO. 09 / 2017 Thammasat Institute of Area Studies, Thammasat University Working Paper Series 2017 Regional Distribution of Foreign Investment in Lao PDR Chanthida Ratanavong Thammasat Institute of Area Studies, Thammasat University 99 Moo 18 Khlongnueng Sub District, Khlong Luang District, Pathum Thani, 12121, Thailand ©2017 by Chanthida Ratanavong. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit including © notice, is given to the source. This publication of Working Paper Series is part of Master of Arts in Asia-Pacific Studies Program, Thammasat Institute of Area Studies (TIARA), Thammasat University. The view expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the Institute. For more information, please contact Academic Support Unit, Thammasat Institute of Area Studies (TIARA), Patumthani, Thailand Telephone: +02 696 6605 Fax: + 66 2 564-2849 Email: [email protected] Language Editors: Mr Mohammad Zaidul Anwar Bin Haji Mohamad Kasim Ms. Thanyawee Chuanchuen TIARA Working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. Comments on this paper should be sent to the author of the paper, Ms. Chanthida Ratanavong, Email: [email protected] Or Academic Support Unit (ASU), Thammasat Institute of Area Studies, Thammasat University Abstract The surge of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is considered to be significant in supporting economic development in Laos, of which, most of the investments are concentrated in Vientiane.