Vector 72 Fowler 1976-02

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS Page(s) not included in the original manuscript are unavailable from the author or university. The manuscript was microfilmed as received 88-91 This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. AccessinglUMI the World’s Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Mi 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8820263 Leigh Brackett: American science fiction writer—her life and work Carr, John Leonard, Ph.D. -

To Sunday 31St August 2003

The World Science Fiction Society Minutes of the Business Meeting at Torcon 3 th Friday 29 to Sunday 31st August 2003 Introduction………………………………………………………………….… 3 Preliminary Business Meeting, Friday……………………………………… 4 Main Business Meeting, Saturday…………………………………………… 11 Main Business Meeting, Sunday……………………………………………… 16 Preliminary Business Meeting Agenda, Friday………………………………. 21 Report of the WSFS Nitpicking and Flyspecking Committee 27 FOLLE Report 33 LA con III Financial Report 48 LoneStarCon II Financial Report 50 BucConeer Financial Report 51 Chicon 2000 Financial Report 52 The Millennium Philcon Financial Report 53 ConJosé Financial Report 54 Torcon 3 Financial Report 59 Noreascon 4 Financial Report 62 Interaction Financial Report 63 WSFS Business Meeting Procedures 65 Main Business Meeting Agenda, Saturday…………………………………...... 69 Report of the Mark Protection Committee 73 ConAdian Financial Report 77 Aussiecon Three Financial Report 78 Main Business Meeting Agenda, Sunday………………………….................... 79 Time Travel Worldcon Report………………………………………………… 81 Response to the Time Travel Worldcon Report, from the 1939 World Science Fiction Convention…………………………… 82 WSFS Constitution, with amendments ratified at Torcon 3……...……………. 83 Standing Rules ……………………………………………………………….. 96 Proposed Agenda for Noreascon 4, including Business Passed On from Torcon 3…….……………………………………… 100 Site Selection Report………………………………………………………… 106 Attendance List ………………………………………………………………. 109 Resolutions and Rulings of Continuing Effect………………………………… 111 Mark Protection Committee Members………………………………………… 121 Introduction All three meetings were held in the Ontario Room of the Fairmont Royal York Hotel. The head table officers were: Chair: Kevin Standlee Deputy Chair / P.O: Donald Eastlake III Secretary: Pat McMurray Timekeeper: Clint Budd Tech Support: William J Keaton, Glenn Glazer [Secretary: The debates in these minutes are not word for word accurate, but every attempt has been made to represent the sense of the arguments made. -

2018/2019 Season

Saturday, April 6, 2019 1:00 & 6:30 pm 2018/2019 SEASON Great Artists. Great Audiences. Hancher Performances. Kevin McKenzie Kara Medoff Barnett ARTISTIC DIRECTOR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Alexei Ratmansky ARTIST IN RESIDENCE STELLA ABRERA ISABELLA BOYLSTON MISTY COPELAND HERMAN CORNEJO SARAH LANE ALBAN LENDORF GILLIAN MURPHY HEE SEO CHRISTINE SHEVCHENKO DANIIL SIMKIN CORY STEARNS DEVON TEUSCHER JAMES WHITESIDE SKYLAR BRANDT ZHONG-JING FANG THOMAS FORSTER JOSEPH GORAK ALEXANDRE HAMMOUDI BLAINE HOVEN CATHERINE HURLIN LUCIANA PARIS CALVIN ROYAL III ARRON SCOTT CASSANDRA TRENARY KATHERINE WILLIAMS ROMAN ZHURBIN Alexei Agoudine Joo Won Ahn Mai Aihara Nastia Alexandrova Sierra Armstrong Alexandra Basmagy Hanna Bass Aran Bell Gemma Bond Lauren Bonfiglio Kathryn Boren Zimmi Coker Luigi Crispino Claire Davison Brittany DeGrofft* Scout Forsythe Patrick Frenette April Giangeruso Carlos Gonzalez Breanne Granlund Kiely Groenewegen Melanie Hamrick Sung Woo Han Courtlyn Hanson Emily Hayes Simon Hoke Connor Holloway Andrii Ishchuk Anabel Katsnelson Jonathan Klein Erica Lall Courtney Lavine Virginia Lensi Fangqi Li Carolyn Lippert Isadora Loyola Xuelan Lu Duncan Lyle Tyler Maloney Hannah Marshall Betsy McBride Cameron McCune João Menegussi Kaho Ogawa Garegin Pogossian Lauren Post Wanyue Qiao Luis Ribagorda Rachel Richardson Javier Rivet Jose Sebastian Gabe Stone Shayer Courtney Shealy Kento Sumitani Nathan Vendt Paulina Waski Marshall Whiteley Stephanie Williams Remy Young Jin Zhang APPRENTICES Jacob Clerico Jarod Curley Michael de la Nuez Léa Fleytoux Abbey Marrison Ingrid Thoms Clinton Luckett ASSISTANT ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Ormsby Wilkins MUSIC DIRECTOR Charles Barker David LaMarche PRINCIPAL CONDUCTOR CONDUCTOR PRINCIPAL BALLET MISTRESS Susan Jones BALLET MASTERS Irina Kolpakova Carlos Lopez Nancy Raffa Keith Roberts *2019 Jennifer Alexander Dancer ABT gratefully acknowledges: Avery and Andrew F. -

13Th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture

13th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture James F. O’Gorman Non-fiction 38.65 ACROSS THE SEA OF GREGORY BENFORD SF 9.95 SUNS Affluent Society John Kenneth Galbraith 13.99 African Exodus: The Origins Christopher Stringer and Non-fiction 6.49 of Modern Humanity Robin McKie AGAINST INFINITY GREGORY BENFORD SF 25.00 Age of Anxiety: A Baroque W. H. Auden Eclogue Alabanza: New and Selected Martin Espada Poetry 24.95 Poems, 1982-2002 Alexandria Quartet Lawrence Durell ALIEN LIGHT NANCY KRESS SF Alva & Irva: The Twins Who Edward Carey Fiction Saved a City And Quiet Flows the Don Mikhail Sholokhov Fiction AND ETERNITY PIERS ANTHONY SF ANDROMEDA STRAIN MICHAEL CRICHTON SF Annotated Mona Lisa: A Carol Strickland and Non-fiction Crash Course in Art History John Boswell From Prehistoric to Post- Modern ANTHONOLOGY PIERS ANTHONY SF Appointment in Samarra John O’Hara ARSLAN M. J. ENGH SF Art of Living: The Classic Epictetus and Sharon Lebell Non-fiction Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness Art Attack: A Short Cultural Marc Aronson Non-fiction History of the Avant-Garde AT WINTER’S END ROBERT SILVERBERG SF Austerlitz W.G. Sebald Auto biography of Miss Jane Ernest Gaines Fiction Pittman Backlash: The Undeclared Susan Faludi Non-fiction War Against American Women Bad Publicity Jeffrey Frank Bad Land Jonathan Raban Badenheim 1939 Aharon Appelfeld Fiction Ball Four: My Life and Hard Jim Bouton Time Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues Barefoot to Balanchine: How Mary Kerner Non-fiction to Watch Dance Battle with the Slum Jacob Riis Bear William Faulkner Fiction Beauty Robin McKinley Fiction BEGGARS IN SPAIN NANCY KRESS SF BEHOLD THE MAN MICHAEL MOORCOCK SF Being Dead Jim Crace Bend in the River V. -

Science Fiction Review 54

SCIENCE FICTION SPRING T)T7"\ / | IjlTIT NUMBER 54 1985 XXEj V J. JL VV $2.50 interview L. NEIL SMITH ALEXIS GILLILAND DAMON KNIGHT HANNAH SHAPERO DARRELL SCHWEITZER GENEDEWEESE ELTON ELLIOTT RICHARD FOSTE: GEIS BRAD SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW (ISSN: 0036-8377) P.O. BOX 11408 PORTLAND, OR 97211 FEBRUARY, 1985 - VOL. 14, NO. 1 PHONE (503) 282-0381 WHOLE NUMBER 54 RICHARD E. GEIS—editor & publisher ALIEN THOUGHTS.A PAULETTE MINARE', ASSOCIATE EDITOR BY RICHARD E. GE1S ALIEN THOUGHTS.4 PUBLISHED QUARTERLY BY RICHARD E, GEIS FEB., MAY, AUG., NOV. interview: L. NEIL SMITH.8 SINGLE COPY - $2.50 CONDUCTED BY NEAL WILGUS THE VIVISECT0R.50 BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER NOISE LEVEL.16 A COLUMN BY JOUV BRUNNER NOT NECESSARILY REVIEWS.54 SUBSCRIPTIONS BY RICHARD E. GEIS SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW ONCE OVER LIGHTLY.18 P.O. BOX 11408 BOOK REVIEWS BY GENE DEWEESE LETTERS I NEVER ANSWERED.57 PORTLAND, OR 97211 BY DAMON KNIGHT LETTERS.20 FOR ONE YEAR AND FOR MAXIMUM 7-ISSUE FORREST J. ACKERMAN SUBSCRIPTIONS AT FOUR-ISSUES-PER- TEN YEARS AGO IN SF- YEAR SCHEDULE. FINAL ISSUE: IYOV■186. BUZZ DIXON WINTER, 1974.57 BUZ BUSBY BY ROBERT SABELLA UNITED STATES: $9.00 One Year DARRELL SCHWEITZER $15.75 Seven Issues KERRY E. DAVIS SMALL PRESS NOTES.58 RONALD L, LAMBERT BY RICHARD E. GEIS ALL FOREIGN: US$9.50 One Year ALAN DEAN FOSTER US$15.75 Seven Issues PETER PINTO RAISING HACKLES.60 NEAL WILGUS BY ELTON T. ELLIOTT All foreign subscriptions must be ROBERT A.Wi LOWNDES paid in US$ cheques or money orders, ROBERT BLOCH except to designated agents below: GENE WOLFE UK: Wm. -

Website Important Books Final Revised Aug2010

Tom Lombardo’s Library: Important Books on Philosophy, Religion, Evolution, Science, Psychology, Science Fiction, and the Future A - C • Abrahamson, Vickie, Meehan, Mary, and Samuel, Larry The Future Ain’t What it Used to Be. New York: Riverhead Books, 1997. • Ackroyd, Peter The Plato Papers: A Prophecy. New York: Doubleday, 1999. • Adams, Douglas The Ultimate Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. New York: Ballantine, 1979-2002. • Adams, Fred and Laughlin, Greg The Five Ages of the Universe: Inside the Physics of Eternity. New York: The Free Press, 1999. • Adams, Fred Our Living Multiverse: A Book of Genesis in 0+7 Chapters. New York: Pi Press, 2004. • Adler, Alfred Understanding Human Nature. (1927) Greenwich, CT: Fawcett Publications, 1965. • Aldiss, Brian Billion Year Spree: The True History of Science Fiction. New York: Schocken Books, 1973. • Aldiss, Brian and Wingrove, David Trillion Year Spree: The History of Science Fiction. North Yorkshire, UK: House of Stratus, 1986. • Allman, William Apprentices of Wonder: Inside the Neural Network Revolution. Bantam, 1989. • Amis, Kingsley and Conquest, Robert (Ed.) Spectrum Vols. 1-5. New York: Berkley, 1961-1966. • Ammerman, Robert (Ed.) Classics in Analytic Philosophy. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1965. • Anderson, Poul Brainwave. New York: Ballantine Books, 1954. • Anderson, Poul Time and Stars. New York: Doubleday, 1964. • Anderson, Poul The Horn of Time. New York: Signet Books, 1968. • Anderson, Poul Fire Time. New York: Ballantine Books, 1974. • Anderson, Poul The Boat of a Million Years. New York: Tom Doherty Associates, 1989. • Anderson, Walter Truett Reality Isn’t What It Used To Be. New York: Harper, 1990. • Anderson, Walter Truett (Ed.) The Truth About the Truth: De-Confusing and Re Constructing the Postmodern World. -

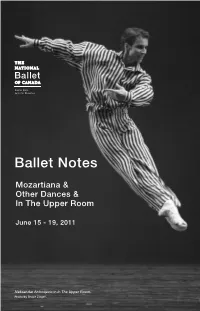

Ballet Notes

Ballet Notes Mozartiana & Other Dances & In The Upper Room June 15 - 19, 2011 Aleksandar Antonijevic in In The Upper Room. Photo by Bruce Zinger. Orchestra Violins Bassoons Benjamin BoWman Stephen Mosher, Principal Concertmaster JerrY Robinson LYnn KUo, EliZabeth GoWen, Assistant Concertmaster Contra Bassoon DominiqUe Laplante, Horns Principal Second Violin Celia Franca, C.C., Founder GarY Pattison, Principal James AYlesWorth Vincent Barbee Jennie Baccante George Crum, Music Director Emeritus Derek Conrod Csaba KocZó Scott WeVers Karen Kain, C.C. Kevin Garland Sheldon Grabke Artistic Director Executive Director Xiao Grabke Trumpets David Briskin Rex Harrington, O.C. NancY KershaW Richard Sandals, Principal Music Director and Artist-in-Residence Sonia Klimasko-LeheniUk Mark Dharmaratnam Principal Conductor YakoV Lerner Rob WeYmoUth Magdalena Popa Lindsay Fischer JaYne Maddison Trombones Principal Artistic Coach Artistic Director, Ron Mah DaVid Archer, Principal YOU dance / Ballet Master AYa MiYagaWa Robert FergUson WendY Rogers Peter Ottmann Mandy-Jayne DaVid Pell, Bass Trombone Filip TomoV Senior Ballet Master Richardson Tuba Senior Ballet Mistress Joanna ZabroWarna PaUl ZeVenhUiZen Sasha Johnson Aleksandar AntonijeVic, GUillaUme Côté*, Violas Harp Greta Hodgkinson, Jiˇrí Jelinek, LUcie Parent, Principal Zdenek KonValina, Heather Ogden, Angela RUdden, Principal Sonia RodrigUeZ, Piotr StancZYk, Xiao Nan YU, Theresa RUdolph KocZó, Timpany Bridgett Zehr Assistant Principal Michael PerrY, Principal Valerie KUinka Kevin D. Bowles, Lorna Geddes, -

Rd., Urbana, Ill. 61801 (Stock 37882; $1.50, Non-Member; $1.35, Member) JOURNAL CIT Arizona English Bulletin; V15 N1 Entire Issue October 1972

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 091 691 CS 201 266 AUTHOR Donelson, Ken, Ed. TITLE Science Fiction in the English Class. INSTITUTION Arizona English Teachers Association, Tempe. PUB DATE Oct 72 NOTE 124p. AVAILABLE FROMKen Donelson, Ed., Arizona English Bulletin, English Dept., Ariz. State Univ., Tempe, Ariz. 85281 ($1.50); National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, Ill. 61801 (Stock 37882; $1.50, non-member; $1.35, member) JOURNAL CIT Arizona English Bulletin; v15 n1 Entire Issue October 1972 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$5.40 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Booklists; Class Activities; *English Instruction; *Instructional Materials; Junior High Schools; Reading Materials; *Science Fiction; Secondary Education; Teaching Guides; *Teaching Techniques IDENTIFIERS Heinlein (Robert) ABSTRACT This volume contains suggestions, reading lists, and instructional materials designed for the classroom teacher planning a unit or course on science fiction. Topics covered include "The Study of Science Fiction: Is 'Future' Worth the Time?" "Yesterday and Tomorrow: A Study of the Utopian and Dystopian Vision," "Shaping Tomorrow, Today--A Rationale for the Teaching of Science Fiction," "Personalized Playmaking: A Contribution of Television to the Classroom," "Science Fiction Selection for Jr. High," "The Possible Gods: Religion in Science Fiction," "Science Fiction for Fun and Profit," "The Sexual Politics of Robert A. Heinlein," "Short Films and Science Fiction," "Of What Use: Science Fiction in the Junior High School," "Science Fiction and Films about the Future," "Three Monthly Escapes," "The Science Fiction Film," "Sociology in Adolescent Science Fiction," "Using Old Radio Programs to Teach Science Fiction," "'What's a Heaven for ?' or; Science Fiction in the Junior High School," "A Sampler of Science Fiction for Junior High," "Popular Literature: Matrix of Science Fiction," and "Out in Third Field with Robert A. -

Hell's Cartographers : Some Personal Histories of Science Fiction Writers

Some Personal Histor , of Science Fiction Writers Robert Silverberg/Alfred Bester Harry Harrison/Damon Knight Frederick Pohl/Brian Aldiss BOSTON PUBLIC LIBRARY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/hellscartographeOObest hell’s cartographers hell’s cartographers Some Personal Histories of Science Fiction Writers with contributions by Alfred Bester Damon Knight Frederik Pohl Robert Silverberg Harry Harrison Brian W. Aldiss Edited by Brian W. Aldiss Harry Harrison HARPER & ROW, PUBLISHERS New York, Hagerstown, San Francisco, London Note: The editors wish to state that the individual contributors to this volume are responsible only for their own opinions and statements. hell’s cartographers. Copyright ©1975 by SF Horizons Ltd. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc., 10 East 53rd Street, New York, N.Y. 10022. FIRST U.S. EDITION Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: Hell’s cartographers. Bibliography: p. 1. Authors, American — Biography. 2. Aldiss, Brian Wilson, 1925- — Biography. 3. Science fiction, American — History and criticism — Addresses, essays, lectures. 4. Science fiction— Authorship. I. Aldiss, Brian Wilson, 1925- II. Harrison, Harry. PS129.H4 1975 813 / .0876 [B] 75-25074 ISBN 0-06-010052-4 76 77 78 79 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Introduction 1 Robert Silverberg: Sounding Brass, Tinkling Cymbal 7 Alfred Bester: My Affair With Science Fiction 46 Harry Harrison: The Beginning of the Affair 76 Damon Knight: Knight Piece 96 Frederik Pohl: Ragged Claws 144 Brian Aldiss: Magic and Bare Boards 173 Appendices: How We Work 211 Selected Bibliographies 239 A section of illustrations follows page 122 Introduction A few years ago, there was a man living down in Galveston or one of those ports on the Gulf of Mexico who helped make history. -

Gilgamesh the King, 2013, 424 Pages, Robert Silverberg, 1480418188, 9781480418189, Open Road Media, 2013

Gilgamesh the King, 2013, 424 pages, Robert Silverberg, 1480418188, 9781480418189, Open Road Media, 2013 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1AC7zag http://www.goodreads.com/search?utf8=%E2%9C%93&query=Gilgamesh+the+King A thrilling retelling of the Epic of Gilgamesh, by one of the greatest storytellers of his generationGilgamesh’s appetite for wine, women, and warfare is insatiable. As the King of Uruk, he oppresses his people and burdens his city. To temper his excesses, the gods create Enkidu, Gilgamesh’s equal, who becomes his greatest friend. Together they wander the kingdom as brothers, conquering demons until a cruel twist changes Gilgamesh’s path forever. Two parts god and one part man, Gilgamesh is mortal—a fate he now resolves to overcome, no matter what the price. And so he embarks on another journey, in pursuit of vengeance and the ultimate prize for a mortal king: eternal life. This ebook features an illustrated biography of Robert Silverberg including rare images and never-before-seen documents from the author’s personal collection. DOWNLOAD http://u.to/gk3TM0 http://bit.ly/1jt7CrN Strange Gifts Science Fiction Stories by Alfred Bester, Gordon R. Dickson, Philip K. Dick, and More!, Robert Silverberg, Mar 1, 2009, Fiction, 208 pages. Included: "The Golden Man," by Philip K. Dick; "Danger -- Human!" by Gordon R. Dickson; "All the People," by R.A. Lafferty; "Oddy and Id," by Alfred Bester; "The Man with. A Century of Fantasy 1980-1989, Martin Harry Greenberg, Robert Silverberg, Jan 1, 1997, Fiction, 352 pages. The Queen of Springtime , Robert Silverberg, May 14, 2013, Fiction, 570 pages. -

SF Commentary 20

- - ..... .. - - -- S F COMMENTARY ' 2 O Anderson Blish Bout land Foyster Gillam Gillespie _e Guin _em _utt rell Miesel Pauls van der Poorten Robb Temple Thaon DISCUSSED IN THIS ISSUE (S F COMMENTARY 20 CHECKLIST) ADELAIDE UNIVERSITY SCIENCE FICTION ASSOCIATION (9, 10) * John Alderson (ed.)s CHAO (10) * Brian Aldiss: THE SERPENT OF KUNDALINI (19) * J G Ballard: THE DEATH MODULE (18) * John Bangsund (ed.)s AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE FICTION MONTHLY (9, 43) * Richard Bergeron (ed.): WARHOON (12) * Mervyn Binns (manager): SPACE AGE COCKSHOP (9) * James Blish (ed.): NEBULA AWARD STORIES 5 (21-22) * Jorge Luis Borges (33-38) * Jorge Luis Borges: ALEPH (35) * Jorge Luis Broges: DEUTSCHES REQUIEM (36) * Jorge Luis Borges: HOUSE OF ASTERION (36) * Jorge Luis Borges: THE IMMORTAL (36) * Jorge Luis Borges: LABYRINTHS (33-38) * Jorge Luis Borges: THE LOTTERY OF BABYLON (33-34).. ..Jor.g^-4e«i^. Borges: PIER.RE MENARD, AUTHOR OF THE 'DuN'QUIXOTE (34):' * Jorge Luis Borges;} THE THEOLOGIANS (36) * Jorge Luis Borges:3orges: THEME OF THE TRAITORJ& THE HERO (36) * Jorge Luis Borges: THREE VERSIONS OF THE JUDAS (34, 37) * Jorge Luis Borges: TLON, UQBAR, ORBIUS TERTIUS (33, 35) * Charles & Dena Brown (eds.): LOCUS (3) * Charles & Dena Brown (organizers): LOCUS POLL (11-12) * Frederick Browns THE WAVERIES (14) * Kevin Brownlow & Andrew Mollo(dirs.)s IT HAPPENED HERE (8) * John Brunner: CATCH A FALLING STAR (27-28) * John Brunners TIME SCOOP (28) * Italo Calvino (50) * Italo Calvino: PRISCILLA (50) * Italo Calvino: T ZERO (TIME & THE HUNTER) (11) * Thomas Clareson -

Feast of Laughter #4

An Appreciation of R. A. Lafferty Fourth Edition - February, 2017 Ktistec Press Feast of Laughter: Volume 4 Feast of Laughter An Appreciation of R. A. Lafferty Volume 4, February 1, 2017 Published by The Ktistec Press All works in this volume copyright © 2017, unless otherwise stated. All copyrights held by the original authors and artists, unless otherwise stated. All works used with permission of the copyright holders. Front cover: “Facing the Storm” © 2016, Ward Shipman Rear cover: “Thoughts on The Rod and the Ring” © 2017 Ward Shipman. Cover layout: Anthony Ryan Rhodes ISBN-13: 978-0998536408 ISBN-10: 0998536407 Contact: Feast of Laughter The Ktistec Press 10745 N. De Anza Blvd. Unit 313 Cupertino, CA 95014 www.feastoflaughter.org [email protected] ii Table of Contents At the Twenty-Fifth Hour – Introduction Introduction - It Must Not End ..................................................... 8 The Shape of Things to Come – New Essays Graced Narratives: Themes of Gift and Will in R.A. Lafferty by John Ellison ....................................................................... 12 Lafferty and Milford by Andrew Ferguson ............................... 27 “There Are Three Ways to Open a Secret Door”: R.A. Lafferty’s Bricolage Aesthetic by Gregorio Montejo ............................................................ 31 On Thunder Mountain – Lightning Essays R. A. Lafferty and the Praise of Power by Jonathan Braschler ......................................................... 137 An Incidence of Coincidence by Russell M. Burden