Stonewall and the Creation of Lesbian, Bisexual, Gay, and Transgender Community and Identity Through Public History Techniques

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

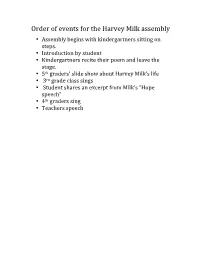

Order of Events for the Harvey Milk Assembly • Assembly Begins with Kindergartners Sitting on Steps

Order of events for the Harvey Milk assembly • Assembly begins with kindergartners sitting on steps. • Introduction by student • Kindergartners recite their poem and leave the stage. • 5th graders’ slide show about Harvey Milk’s life • 3rd grade class sings • Student shares an excerpt from Milk’s “Hope speech” • 4th graders sing • Teachers speech Student 1 Introduction Welcome students of (School Name). Today we will tell you about Harvey Milk, the first gay City Hall supervisor. He has changed many people’s lives that are gay or lesbian. People respect him because he stood up for gay and lesbian people. He is remembered for changing our country, and he is a hero to gay and lesbian people. Fifth Grade Class Slide Show When Harvey Milk was a little boy he loved to be the center of attention. Growing up, Harvey was a pretty normal boy, doing things that all boys do. Harvey was very popular in school and had many friends. However, he hid from everyone a very troubling secret. Harvey Milk was homosexual. Being gay wasn’t very easy back in those days. For an example, Harvey Milk and Joe Campbell had to keep a secret of their gay relationship for six years. Sadly, they broke up because of stress. But Harvey Milk was still looking for a spouse. Eventually, Harvey Milk met Scott Smith and fell in love. Harvey and Scott moved together to the Castro neighborhood of San Francisco, which was a haven for people who were gay, a place where they were respected more easily. Harvey and Scott opened a store called Castro Camera and lived on the top floor. -

LGBTQ America: a Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. THEMES The chapters in this section take themes as their starting points. They explore different aspects of LGBTQ history and heritage, tying them to specific places across the country. They include examinations of LGBTQ community, civil rights, the law, health, art and artists, commerce, the military, sports and leisure, and sex, love, and relationships. MAKING COMMUNITY: THE PLACES AND15 SPACES OF LGBTQ COLLECTIVE IDENTITY FORMATION Christina B. Hanhardt Introduction In the summer of 2012, posters reading "MORE GRINDR=FEWER GAY BARS” appeared taped to signposts in numerous gay neighborhoods in North America—from Greenwich Village in New York City to Davie Village in Vancouver, Canada.1 The signs expressed a brewing fear: that the popularity of online lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) social media—like Grindr, which connects gay men based on proximate location—would soon replace the bricks-and-mortar institutions that had long facilitated LGBTQ community building. -

A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. PRESERVING LGBTQ HISTORY The chapters in this section provide a history of archival and architectural preservation of LGBTQ history in the United States. An archeological context for LGBTQ sites looks forward, providing a new avenue for preservation and interpretation. This LGBTQ history may remain hidden just under the ground surface, even when buildings and structures have been demolished. THE PRESERVATION05 OF LGBTQ HERITAGE Gail Dubrow Introduction The LGBTQ Theme Study released by the National Park Service in October 2016 is the fruit of three decades of effort by activists and their allies to make historic preservation a more equitable and inclusive sphere of activity. The LGBTQ movement for civil rights has given rise to related activity in the cultural sphere aimed at recovering the long history of same- sex relationships, understanding the social construction of gender and sexual norms, and documenting the rise of movements for LGBTQ rights in American history. -

Thematic Review: American Gay Rights Movement Directions and Obje

Name:_____________________________________ Class Period:______ Thematic Review: American Gay Rights Movement Although the topic of homosexuality continues to ignite passionate debate and is often omitted from history discussions due to the sensitivity of the topic, it is important to consider gays and lesbians when defining and analyzing modern American identity. The purpose of this activity is to review the struggle for respect, dignity, and equal protection under the law that so many have fought for throughout American history. Racial minorities… from slaves fighting for freedom to immigrants battling for opportunity… to modern-day racial and ethnic minorities working to overcome previous and current inequities in the American system. Women… fighting for property rights, education, suffrage, divorce, and birth control. Non- Protestants… from Catholics, Mormons, and Jews battling discrimination to modern day Muslims and others seeking peaceful co-existence in this “land of the free.” Where do gays and lesbians fit in? Once marginalized as criminals and/or mentally ill, they are increasingly being included in the “fabric” we call America. From the Period 8 Content Outline: Stirred by a growing awareness of inequalities in American society and by the African American civil rights movement, activists also addressed issues of identity and social justice, such as gender/sexuality and ethnicity. Activists began to question society’s assumptions about gender and to call for social and economic equality for women and for gays and lesbians. Directions and Objectives: Review the events in the Gay Rights Thematic Review Timeline, analyze changes in American identity, and make connections to other historically significant events occurring along the way. -

![Barbara Gittings and Kay Tobin Lahusen Collection, 1950-2009 [Bulk: 1964-1975] : Ms.Coll.3](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2283/barbara-gittings-and-kay-tobin-lahusen-collection-1950-2009-bulk-1964-1975-ms-coll-3-92283.webp)

Barbara Gittings and Kay Tobin Lahusen Collection, 1950-2009 [Bulk: 1964-1975] : Ms.Coll.3

Barbara Gittings and Kay Tobin Lahusen collection, 1950-2009 [Bulk: 1964-1975] : Ms.Coll.3 Finding aid prepared by Alina Josan on 2015 PDF produced on July 17, 2019 John J. Wilcox, Jr. LGBT Archives, William Way LGBT Community Center 1315 Spruce Street Philadelphia, PA 19107 [email protected] Barbara Gittings and Kay Tobin Lahusen collection, 1950-2009 [Bulk: 1964-1975] : Ms.Coll.3 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical ................................................................................................................................ 4 Scope and Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 7 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 8 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 8 Subject files ................................................................................................................................................ -

Sip-In" That Drew from the Civil Rights Movement by History.Com, Adapted by Newsela Staff on 11.07.19 Word Count 887 Level 1020L

The gay "sip-in" that drew from the civil rights movement By History.com, adapted by Newsela staff on 11.07.19 Word Count 887 Level 1020L Image 1. A bartender in Julius's Bar refuses to serve John Timmins, Dick Leitsch, Craig Rodwell and Randy Wicker, members of the Mattachine Society, an early American gay rights group, who were protesting New York liquor laws that prevented serving gay customers on April 21, 1966. Photo from: Getty Images/Fred W. McDarrah. In 1966, on a spring afternoon in Greenwich Village, three men set out to change the political and social climate of New York City. After having gone from one bar to the next, the men reached a cozy tavern named Julius'. They approached the bartender, proclaimed they were gay and then requested a drink, but were promptly denied service. The trio had accomplished their goal: their "sip-in" had begun. The men belonged to the Mattachine Society, an early organization dedicated to fighting for gay rights. They wanted to show that bars in the city discriminated against gay people. Discrimination against the gay community was a common practice at the time. Still, this discrimination was less obvious than the discriminatory Jim Crow laws in the South that forced racial segregation. Bartenders Refused Service To Gay Couples This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. A person's sexual orientation couldn't be detected as easily as a person's sex or race. With that in mind, the New York State Liquor Authority, a state agency that controls liquor sales, took action. -

Homophobia and Transphobia Illumination Project Curriculum

Homophobia and Transphobia Illumination Project Curriculum Andrew S. Forshee, Ph.D., Early Education & Family Studies Portland Community College Portland, Oregon INTRODUCTION Homophobia and transphobia are complicated topics that touch on core identity issues. Most people tend to conflate sexual orientation with gender identity, thus confusing two social distinctions. Understanding the differences between these concepts provides an opportunity to build personal knowledge, enhance skills in allyship, and effect positive social change. GROUND RULES (1015 minutes) Materials: chart paper, markers, tape. Due to the nature of the topic area, it is essential to develop ground rules for each student to follow. Ask students to offer some rules for participation in the postperformance workshop (i.e., what would help them participate to their fullest). Attempt to obtain a group consensus before adopting them as the official “social contract” of the group. Useful guidelines include the following (Bonner Curriculum, 2009; Hardiman, Jackson, & Griffin, 2007): Respect each viewpoint, opinion, and experience. Use “I” statements – avoid speaking in generalities. The conversations in the class are confidential (do not share information outside of class). Set own boundaries for sharing. Share air time. Listen respectfully. No blaming or scapegoating. Focus on own learning. Reference to PCC Student Rights and Responsibilities: http://www.pcc.edu/about/policy/studentrights/studentrights.pdf DEFINING THE CONCEPTS (see Appendix A for specific exercise) An active “toolkit” of terminology helps support the ongoing dialogue, questioning, and understanding about issues of homophobia and transphobia. Clear definitions also provide a context and platform for discussion. Homophobia: a psychological term originally developed by Weinberg (1973) to define an irrational hatred, anxiety, and or fear of homosexuality. -

STONEWALL Riotsstro

Everyday hero. Ordinary world. Compelling villain. Call to adventure. Crossing the threshold. STONEWALL RIOTS STONEWALL strongerstories.org Allies, mentors and gifts. Three challenges. Better world. Everyday hero. Ordinary world. Compelling villain. Call to adventure. Crossing the threshold. The Stonewall Inn The 1960s were difficult Thanks to activists Raid: 1:20 a.m. Procedure was to line up community – an important for LGBTQ+ Americans. alcohol regulations were 28/06/1969, 6 policemen, the patrons, check their Greenwich Village Solicitation of same-sex overturned. But engaging 1 detective and 1 ID, and have police institution. The relations was illegal in in homosexual behaviour inspector arrived yelling officers take customers Stonewall Inn was large, New York, and there was in public (holding "Police! We're taking the to the toilet to verify RIOTS STONEWALL cheap to enter, welcomed a criminal statute that hands, kissing, dancing) place!” Stonewall their sex. That night Drag Queens (others allowed police to arrest was still illegal, so employees do not recall customers refused to go usually didn't) and it people wearing less than police harassment being tipped off that a with the officers. Stormé was a nightly home for three gender-appropriate continued. Rampant raid was to occur, as was DeLarverie fought back many runaway homeless clothes. The State institutionalised the custom. The music was against the police LGBTQ+ youths. It was Liquor Authority homophobia and turned off and the lights officer who attempted to one of the few - if not penalised and shut down transphobia – the turned on, and the police arrest her. She shouted the only – LGBTQ+ bar establishments that Stonewall Riots specific barricaded the doors. -

LGBT History

LGBT History Just like any other marginalized group that has had to fight for acceptance and equal rights, the LGBT community has a history of events that have impacted the community. This is a collection of some of the major happenings in the LGBT community during the 20th century through today. It is broken up into three sections: Pre-Stonewall, Stonewall, and Post-Stonewall. This is because the move toward equality shifted dramatically after the Stonewall Riots. Please note this is not a comprehensive list. Pre-Stonewall 1913 Alfred Redl, head of Austrian Intelligence, committed suicide after being identified as a Russian double agent and a homosexual. His widely-published arrest gave birth to the notion that homosexuals are security risks. 1919 Magnus Hirschfeld founded the Institute for Sexology in Berlin. One of the primary focuses of this institute was civil rights for women and gay people. 1933 On January 30, Adolf Hitler banned the gay press in Germany. In that same year, Magnus Herschfeld’s Institute for Sexology was raided and over 12,000 books, periodicals, works of art and other materials were burned. Many of these items were completely irreplaceable. 1934 Gay people were beginning to be rounded up from German-occupied countries and sent to concentration camps. Just as Jews were made to wear the Star of David on the prison uniforms, gay people were required to wear a pink triangle. WWII Becomes a time of “great awakening” for queer people in the United States. The homosocial environments created by the military and number of women working outside the home provide greater opportunity for people to explore their sexuality. -

The 2014 Bisexual/Pansexual/Fluid Community Needs Assessment of Greater Los Angeles

The 2014 Bisexual/Pansexual/Fluid Community Needs Assessment of Greater Los Angeles Publisher: Los Angeles Bi Task Force Los Angeles, California Principle Investigator: Mimi Hoang, Ph.D., www.drmimihoang.com Published By: Los Angeles Bi Task Force, Los Angeles, California, March 2015 Special Thanks To: Cadyn Cathers, M.A. Royanna Lecuyer-Mangel, M.A. Lori Way, M.A. Tara Avery Yazmin Monet Watkins Anais Plasketes, M.A. Robert Ozn Curt Duffy William Burleson Lauren Beach Dr. Herukhuti Kathleen Sullivan, Ph.D. Ian lawrence Mike Szymanski Eunice Gonzalez ____________________________________________________________________________ LABTF is a non-profit that promotes education, advocacy, and cultural enrichment for the bisexual, pansexual, and fluid communities in Greater LA. 1 Table of Contents Introduction........................................................................................................ ........................... 3 History of Greater Los Angeles Bisexual Communities............................................................... .. 3 Goal of This Assessment............................................................................................................. 4 Methods……................................................................................................................................ 4 Summary of Findings.................................................................................................................... 5 Demographics .................................................................................................................... -

The Spark of Stonewall

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by James Madison University James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Proceedings of the Sixth Annual MadRush MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference Conference: Best Papers, Spring 2015 A Movement on the Verge: The pS ark of Stonewall Tiffany Renee Nelson James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.lib.jmu.edu/madrush Part of the Social History Commons Tiffany Renee Nelson, "A Movement on the Verge: The pS ark of Stonewall" (April 10, 2015). MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference. Paper 1. http://commons.lib.jmu.edu/madrush/2015/SocialMovements/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conference Proceedings at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Movement on the Verge: The Spark of Stonewall The night of Saturday, June 28, 1969, the streets of Central Greenwich Village were crowded with angered gay men, lesbians, “flame queens”, and Trans*genders. 1 That was the second day of disorder of what would later be called the Stonewall Riots. Centering around Christopher Street’s bar for homosexuals, the Stonewall Inn, the riots began the night before on June 27 and lasted until July 2. These five days of rioting were the result of decades of disdain against the police force and the general population that had oppressed the gay inhabitants of New York City. -

Brief Amici Curiae of Dr. Judith Reisman and the Child

No. 16-273 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES GLOUCESTER COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, Petitioner, v. G.G. by her next friend and mother, DEIRDRE GRIMM, Respondent On Writ of Certiorari to the U.S. Court Of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE DR. JUDITH REISMAN AND THE CHILD PROTECTION INSTITUTE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER Mathew D. Staver Mary E. McAlister (Counsel of Record) LIBERTY COUNSEL Anita L. Staver PO Box 11108 Horatio G. Mihet Lynchburg, VA 24506 LIBERTY COUNSEL (407) 875-1776 PO Box 540774 [email protected] Orlando, FL 327854 (407) 875-1776 [email protected] i TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ........................ ivv INTEREST OF AMICI .................................... 1 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ..................................................... 2 LEGAL ARGUMENT ...................................... 6 I. THIS COURT SHOULD REJECT THE DEPARTMENTS’ DIRECTIVE BECAUSE THERE IS NO SCIENTIFIC EVIDENCE FOR THE CONCEPT OF A DIFFERENTIAL “GENDER IDENTITY.” ........................................ 6 II. THIS COURT SHOULD GIVE NO EFFECT TO THE DEPARTMENTS’ INTERPRETATION BECAUSE IT REPLACES SCIENTIFIC REALITY WITH AN ARTIFICIAL SOCIAL CONSTRUCT BUILT UPON CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE, FRAUD AND HUMAN EXPERIMENTATION. ................... 20 ii A. Alfred Kinsey Disguises Child Sexual Abuse As Scientific Data On “Pre- Adolescent Orgasm” And Launches The Idea Of Fluid Sexuality. ......................... 21 B. Dr. Harry Benjamin Used Kinsey’s Concepts To Become The Father Of Transsexualism And Posit The Existence of Seven Sexes. ........................................... 26 C. Dr. John Money Used Kinsey’s Model Of Human Experimentation To Develop His Concept Of Transgenderism And Sex “Re-Assignment.” ...................... 30 D. Socio-Political Change Agents Hijack The Language To Further Their Agenda Of Deconstructing Binary Sex.