Pedagogy in the Time of Pandemic: from Localisation to Glocalisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Cook University 2.56

November 2010 This report is commissioned by: Aventis School of Management,100 Orchard Road #04-100 www.aventis.edu.sg Articles and Research are contributed by: Edupoll.org , a division of Edugo Global LLC, a leading vertical portal for university education in the region with a reputation for attracting a highly-focused education-seeking audience with online audiences from over 80 countries Copyright Notice: You may not copy, reproduce, transfer, enter into a database, publish, distribute, publicly display, sell or offer for sale, or create derivative works from this document or use it in any way for any public or commercial purpose. For permission to use content from this document or reprints, please contact [email protected] Disclaimer: This report is intended for use as guide to obtain advice with regards to MBA and postgraduate courses offered in Singapore. It contains general information. Although Aventis and Edupoll endeavor to ensure that the content is accurate and up to date, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made to its accuracy or completeness. The contents of this guide should not be construed as professional advice, or recommendation of any product or service offered by the companies providing such products or services. Aventis & Edupoll including its management and staff, disclaims liability for any loss, howsoever caused, arising directly or indirectly from the use and content of this guide All Rights Reserved 2010 TABLE OF CONTENT GETTNG READY MBA Overview ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

3Rd Annual Digital Campus: Remote Teaching, Online

3RD ANNUAL DIGITAL CAMPUS: REMOTE TEACHING, ONLINE BLENDED LEARNING AND EDUCATION CONTINUITY PLANNING FORUM REIMAGINING THE FUTURE OF EDUCATION WITH REMOTE TEACHING AND ONLINE LEARNING C LARIDEN MAIN FORUM: 7-8 DECEMBER 2020 DIGITAL CAMPUS SITE TOURS: 9 DECEMBER 2020 VENUE: ONE FARRER HOTEL SINGAPORE QUESTIONS? Contact us at: +65 6899 5030 [email protected] claridenglobal.com FEATURING TOP EDTECH SPEAKERS AND LEADERS DR. MAY LIM DR. CATHERINE SHEA DR. NACHAMMA Director, Centre for SANGER SOCKALINGAM Learning Environment and Director, Centre for Programme Director of Assessment Development Teaching & Learning Learning Sciences Lab (CoLEAD) Yale-NUS College Singapore University of Singapore Institute of Technology and Design Technology (SIT) (SUTD) How Singapore Institute of How Yale-NUS College Adapted Technology Effectively Migrated Leveraging LMS Teaching During The COVID-19 To Online Teaching During Circuit For Active Learning Pandemic Crisis Breaker ESTHER FINK RAJESH CHAKRAVARTHY LAU KAI CHEONG Learning Technologies Academic Director Vice President, IT & Chief Specialist MAGES Institute of Information Officer James Cook University Excellence Singapore Management University (SMU) How James Cook University How SMU Adopted AI Adopted Blended Learning Teaching In The New Reality: Using In Redefining Teaching & Learning Approaches To Assure Seamless AR And VR To Enhance Learning During Remote Learning Continuity In Education DR. YEUNG SZE KIU DR. SEOW POH SUN DR. FUNG FUN MAN Senior Lecturer, Online Associate Professor of Lecturer in Chemistry and Learning Unit Accounting (Education) Science of Learning SUSS Singapore Management National University of University (SMU) Singapore (NUS) Singapore University Of Social How SMU Is Driving Online Sciences Utilizes Learning How To Maintain Engaging Online Learning Engagement With Analytics To More Effectively Learning Amid COVID-19 Pandemic Integration Of Gamification Manage Students’ Performance DR. -

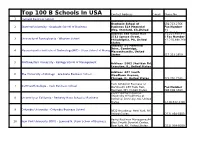

Top 100 B Schools In

Top 100 B Schools In USA Contact Address E-mail Phone No 1 Harvard Business School Address: Stanford +1 Graduate School of 650.723.2766 2 Stanford University - Graduate School of Business Business 518 Memorial Fax Number Way, Stanford, CA,United +1 AddressStates 344 Vance Hall +1.215.898.847650.725.7831 3733 Spruce Street, 8 Fax Number 3 University of Pennsylvania - Wharton School Philadelphia, PA, United +1.215.898.269 States 5 Address :50 Memorial Drive, Cambridge, 4 Massachusetts Institute of Technology(MIT) - Sloan School of ManagementMassachusetts, United States 617-253-2659 5 Northwestern University - Kellogg School of Management Address :2001 Sheridan Rd, Evanston, IL, United States Address :807 South 6 The University of Chicago - Graduate Business School Woodlawn Avenue, Chicago, IL, United States 773.702.7743. Tuck School of Business at 7 Dartmouth College - Tuck Business School Dartmouth 100 Tuck Hall, Fax Number Hanover, NH, United States 603-646-1308 2220 Piedmont Avenue University of California at 8 University of California - Berkeley Haas School of Business Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, United States 1-510-642-1405 9 Columbia University - Columbia Business School 3022 Broadway, New York, NY, United States (212) 854-5553 Henry Kaufman Manageme,44 10 New York University (NYU) - Leonard N. Stern School of Business West Fourth Streetnt Center, New York, NY, United States (212) 998-0100 UCLA Anderson School of 201-825-6944 11 University of California Los Angeles - John E. Anderson School of ManagementManagement Box 951481, Los Fax Number AngelesStephen ,M. CA, Ross United School States of 201-825-8582 Business University of Michigan 701 Tappan 12 The University of Michigan - Stephen M. -

Online MBA Programmes Emerge As Pandemic Prompts Temporary Closures Some of the Top MBA Providers Are Planning to Launch Online Programmes in the Future

RANKINGS: MBA PROGRAMMES AND PROVIDERS S P Jain main branch Online MBA programmes emerge as pandemic prompts temporary closures Some of the top MBA providers are planning to launch online programmes in the future. n this year’s Singapore Business Aventis School of Management As executives Management. Review rankings of the largest academic director Stanley Soh become Aventis is also currently in talks IMBA programmes, INSEAD told Singapore Business Review that strapped for about launching an online MBA MBA emerged on top, with a they received a spike in requests time, balancing programme, after digitising some of whopping 1,008 students enrolled in from prospective students who are their careers their Graduate Diploma programme. the programme. It is followed by S P considering taking an online MBA, and personal Further, Kaplan Higher Education Jain Master of Global Business with especially in light of the COVID-19 commitments, is considering the possibility of 239 students, and Manchester Global pandemic and the increasing online MBA launching online MBA programmes. Master of Business Administration by digitisation of business school programmes Currently, they are offering an online Alliance Manchester Business School offerings. will see a surge Master’s programme for Executive with 219. In response to such demand, in popularity. Master in Leadership and Strategy Amongst MBA providers, INSEAD MBA providers have increasingly and Innovation, in partnership with with just its sole MBA programme been bringing such programmes Murdoch University. still has the most number of MBA in Singapore. For instance, a “We believe an online MBA students, followed by S P Jain School spokesperson from the Management programme will help our students as of Global Management and the Development Institute of Singapore it offers greater flexibility in terms of National University of Singapore (MDIS) shared that they are offering managing their time and not being (NUS) Business School with 509 and five online or e-learning MBA confined to a classroom setting. -

Newsletter May 2018

May 2018 ACS (INTERNATIONAL) NEWSLETTER IN THIS ISSUE Dear Parents, Students and Friends • Staff News Last week we were able to recognise leadership giftings in many of our students at our annual • Term 3 Start Dates Student Leadership Investiture. We thanked the outgoing leaders for their sterling efforts, and National Service Talk invested the incoming leaders into their new roles. It was a significant, formal and memorable • ceremony for all who attended. • Student Leadership Investiture Developing student Leadership is a core goal of our school. Our vision statement is to develop • PSP News future leaders with moral character, intellectual ability, international mindedness and deep compassion for humanity based upon Christian belief and values. • American Protege International Vocal At the Investiture students were advised that leadership takes many forms. There is no one Competition right way. The trailer of the movie, the Darkest Hour, starring Gary Oldman, who recently won an Academy Award for Best Actor for his portrayal of Winston Churchill, was shown to • Sermaine Saw – LCM High Distinction illustrate a few leadership points. Churchill is generally regarded as a great war time leader. th Churchill though was not perfect, a heavier drinker, not very approachable nor well liked, and • 10 ASEAN Schools Games had previous failed military campaigns in World War I; but World War II was his time – the • TKK Charity ProJect phrase ‘cometh the hour, cometh the man’ applies to Churchill at that dire time in British history. • Higher Education Fair Three key points were singled out from Churchill’s leadership. Firstly, you don’t have to be • Careers Week perfect to be a successful leader – Churchill certainly wasn’t – and similarly in our context, we do not expect our student leaders to be perfect, nor the most popular people in the school. -

Newsletter April 2018

April 2018 ACS (INTERNATIONAL) NEWSLETTER IN THIS ISSUE Dear Parents, Students and Friends • Staff News Welcome back to school for Term 2. Many thanks to the parents who attended the recent Parent Teacher Meeting, which we trust was both useful and effective for all • Launch of Callido for Year 5 who participated, and that specific feedback on student progress and how to • Long Weekend Holiday improve their grades was helpful. We were very pleased with the high turnout and the overall interaction between parents, students and teachers. • House T-shirts Thanks also to the whole school community who supported the Open House on • PSP News Saturday 24 March – staff, students, parents and PSP. The turnout was the highest number we have had which was most encouraging. It reflects a trend of continual • Commendation Awards improvement and of community reputation. • National Schools Artistic Swimming Last week in Chapel we held our annual Religious Emphasis Week (REW) programme Championships as part of the lead up to Easter. At REW and at Easter we are reminded of the supreme sacrifice that Jesus made on the cross and of his resurrection three days • SIMUN 2018 later. The death and resurrection of Jesus, which Easter celebrates, is a foundation of the Christian faith. Jesus’ personal sacrifice has given Christians "a new birth into a • World Vision Presentation living hope through the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead" 1 Peter 1:3. In other words, the resurrection of Christ is the cause and source of our new birth into • English Poetry Book Sharing God’s family and the hope we have of our full inheritance as family members when Jesus comes again. -

2018 Offshore Higher Education Student Survey

2018 Offshore Higher Education Student Survey Table of Contents Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................... 3 Results ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Decision factors and influences .............................................................................................. 8 Australian program choice ..................................................................................................... 9 Propensity to recommend .................................................................................................... 10 What matters to students? .................................................................................................. 10 Learning............................................................................................................................ 11 Living ................................................................................................................................ 12 Support............................................................................................................................. 12 Future Plans .............................................................................................................................. 13 Key messages ............................................................................................................................ 14 Appendices -

The Jobscentral Learning Rankings and Survey Series Is the Largest and Most Comprehensive Research on Singapore’S Private Education Landscape

JobsCentral is a CareerBuilder Company. TThehe JJobsCentralobsCentral LLearningearning Rankings and Survey Report 2012 December 2012 A study of the private higher education rankings and learning preferences in Singapore This report is published by: JobsCentral Pte Ltd www.jobscentral.com.sg 3A International Business Park, #08-08, ICON@IBP, Tower A, Singapore 609935 Survey Contacts: Alythea Ho [email protected] | Jonathan Tay [email protected] Copyright © 2012 JobsCentral Pte Ltd This document is copyrighted; any unauthorized use of it may violate copyright, trademark and other laws. For permission to use content from this document or reprints, please contact JobsCentral at [email protected] or call (65) 6778 5288 2012 JobsCentral Learning Rankings and Survey 01 IIntroductionntroduction Since its launch in 2009, the JobsCentral Learning Rankings and Survey series is the largest and most comprehensive research on Singapore’s private education landscape. The report is based on an independent research project commissioned by the JobsCentral Group, and comprises two main categories: rankings of Singapore’s private education institutes, and learning preferences findings of the general population aged 15 and above. 5,476 respondents’ data was collected via a voluntary online questionnaire from September to October this year. Incomplete and duplicated responses were discarded and do not contribute to this count. This report includes findings which may be of interest to employers seeking to understand what motivates employees to pursue further education, and the expected salary increments after obtaining higher qualifications. Prospective adult students may also find the rankings useful in making informed decisions for a school and course of study. -

Students' Declaration

A COMPREHENSIVE REPORT ON Global Country Submitted to INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT UNIVERSE UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF Mrs. Palak Kothari Associate Professor SUBMITTED BY Sr No. Name Enrollment No 1 Roma Patel 118220592007 2 Imran Meman 118220592009 3 Harshal Raval 118220592015 [MBA SEMESTER III & IV] INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT UNIVERSE MBA PROGRAMME Affiliated to Gujarat Technological University Ahmedabad Students’ Declaration We, Roma Patel, Imran Meman, Harshal Raval, hereby declare that the report for Global/ Country Study Report entitled “Education Industry in on China, South Africa And India is a result of our own work and our indebtedness to other work publications, references, if any, have been duly acknowledged. Place : Vadodara (Signature) Date : ( Name Of Student) Roma Patel Imran Meman Harshal Raval Preface As a MBA student of ITM Universe, Vadodara. Affiliated by GTU. we have made report on Global Country Report on Education sector. So we have selected China , India, South Africa To study the Education sector. We have taken all the topics shown in the report to study the sector. We have learnt a lot from this report about Education In all three countries. The policy and norms of all three country also mentioned in the report. The future challenges also mentioned in the report. We thankful to our head of Department Dr. S. K. Vij to helping us to make report and also to Mrs. Palak Kothari. We the help of our faculty member we made this report. 2 This report will help in future. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT It is our pleasure to place on record my sincere gratitude towards Mrs. -

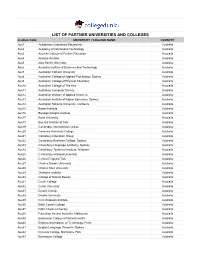

List of Partner Universities and Colleges

LIST OF PARTNER UNIVERSITIES AND COLLEGES Institute Code UNIVERSITY / COLLEGE NAME COUNTRY Aus1 Academies Australasia Polytechnic Australia Aus2 Academy of Information Technology Australia Aus3 Acumen Institute of Further Education Australia Aus4 Airways Aviation Australia Aus5 Asia Pacific University Australia Aus6 Australia Institute of Business And Technology Australia Aus7 Australian Catholic University Australia Aus8 Australian College of Applied Psychology, Sydney Australia Aus9 Australian College of Physical Education Australia Aus10 Australian College of The Arts Australia Aus11 Australian Computer Society Australia Aus12 Australian Institute of Applied Sciences Australia Aus13 Australian Institute of Higher Education, Sydney Australia Aus14 Australian National University, Canberra Australia Aus15 Baxter Institute Australia Aus16 Bendigo Kangan Institute Australia Aus17 Bond University Australia Aus18 Box Hill Institute of Tafe Australia Aus19 Cambridge International College Australia Aus20 Canberra University College Australia Aus21 Cantebury Education Group Australia Aus22 Canterbury Business College, Sydney Australia Aus23 Canterbury Language Academy, Sydney Australia Aus24 Canterbury Technical Institute, Brisbane Australia Aus25 Central Queensland University Australia Aus26 Central Regional Tafe Australia Aus27 Charles Darwin University Australia Aus28 Charles Sturt University Australia Aus29 Chisholm Institute Australia Aus30 College of Natural Beauty Australia Aus31 Curtin College Australia Aus32 Curtin University Australia -

Annual Report

2009 Annual Report Beyond is dedicated to helping children and youth from disadvantaged backgrounds and developing them to value education, respect the law and grow into responsible adults who are capable of breaking out of the poverty cycle. Table of Contents Page 1. The President’s Summary 2-4 2. Introducing Ourselves 5-9 3. Infants & Early Childhood Development 9-11 4. Children, Youth & Restorative Justice Department 11-18 5. Family Service Department 19-20 6. Residential & Child Protection Department 21-23 7. Partnership & Talent Development Department 24-25 8. Finance & Administration Department 25-26 9. Those Who Dug Into Their Pockets 27-30 10. Saying Thanks 30-35 11. Report and Financial Statements 36-66 1 The President’s Summary We entered our 40 th year of service anticipating and gearing ourselves for the challenges of the economic downturn in 2009. With reduced employment opportunities, the demand for social services will rise whilst reduced resources for poor families would bring forth more marital and parent-child conflicts. Facing the economic downturn Keeping a close watch on the situation meant Beyond was better able to organise resources to provide the financial assistance needed to prevents families from spiralling downwards. During the course of the year, we handled an average of 30 new cases per month at our Family Service Centre. By the end of the year, we had disbursed $205,167.84 to 631 beneficiaries. Compared to our efforts in 2008, this was an increase of over $31,000 in funds disbursement to an additional 36 beneficiaries. We were able to connect most of those seeking assistance to various schemes and resources in the community that are available to those in need. -

Country University

The university policy index captures the recognition policies reported to the IB by universities from around the world. This index allows you to filter by country and/or university name. The IB Student Registry (https://registry.ibo.org/) is the newly launched IB platform to connect IB schools and students with universities & colleges. The registry allows universities to create profiles outlining the various components of their IB recognition policies, including credits and scholarships awarded. This new platform will eventually replace this index. While the IB Student Registry is being introduced, this index will remain available to interested parties. But please note that the information presented here was last updated October 2015. We recommend visiting the university websites for the most up to date information and recognition policies. If you have any questions about recognition or the IB Student Registry, please email us at [email protected] or [email protected]. Country University ANTIGUA AND University of Health BARBUDA Sciences Antigua ARGENTINA Escuela Superior Técnica del Ejército Argentino ARGENTINA ESEADE - Instituto Universitario ARGENTINA Instituto Tecnológico de Buenos Aires (ITBA) ARGENTINA Instituto Universitario CEMIC ARGENTINA International Buenos Aires Hotel & Restaurant School (IBAHRS ARGENTINA Lincoln University College ARGENTINA Ott College ARGENTINA Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina ARGENTINA Universidad Abierta Interamericana ARGENTINA Universidad Argentina de la Empresa ARGENTINA Universidad Austral