1 Geography and Innovation in Rock and Roll a Senior Honors Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century Saesha Senger University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2020.011 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Senger, Saesha, "Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 150. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/150 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Bob Dylan Performs “It's Alright, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding),” 1964–2009

Volume 19, Number 4, December 2013 Copyright © 2013 Society for Music Theory A Foreign Sound to Your Ear: Bob Dylan Performs “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding),” 1964–2009 * Steven Rings NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.13.19.4/mto.13.19.4.rings.php KEYWORDS: Bob Dylan, performance, analysis, genre, improvisation, voice, schema, code ABSTRACT: This article presents a “longitudinal” study of Bob Dylan’s performances of the song “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” over a 45-year period, from 1964 until 2009. The song makes for a vivid case study in Dylanesque reinvention: over nearly 800 performances, Dylan has played it solo and with a band (acoustic and electric); in five different keys; in diverse meters and tempos; and in arrangements that index a dizzying array of genres (folk, blues, country, rockabilly, soul, arena rock, etc.). This is to say nothing of the countless performative inflections in each evening’s rendering, especially in Dylan’s singing, which varies widely as regards phrasing, rhythm, pitch, articulation, and timbre. How can music theorists engage analytically with such a moving target, and what insights into Dylan’s music and its meanings might such a study reveal? The present article proposes one set of answers to these questions. First, by deploying a range of analytical techniques—from spectrographic analysis to schema theory—it demonstrates that the analytical challenges raised by Dylan’s performances are not as insurmountable as they might at first appear, especially when approached with a strategic and flexible methodological pluralism. -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center). All recordings received are included in “Publication Noted” (which follows “Off the Beaten Track”). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention “Off The Beaten Track.” Sincere thanks to this issue’s panel of musical experts: Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Seth Rogovoy, Ken Roseman, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Theodoros Toskos, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Rob Weir and Sule Greg Wilson. that led to a career traveling across coun- the two keyboard instruments. How I try as “The Singing Troubadour.” He per- would have loved to hear some of the more formed in a variety of settings with a rep- unusual groupings of instruments as pic- ertoire that ranged from opera to traditional tured in the notes. The sound of saxo- songs. He also began an investigation of phones, trumpets, violins and cellos must the music of various utopian societies in have been glorious! The singing is strong America. and sincere with nary a hint of sophistica- With his investigation of the music of tion, as of course it should be, as the Shak- VARIOUS the Shakers he found a sect which both ers were hardly ostentatious. -

Sound Recording in the British Folk Revival: Ideology, Discourse and Practice, 1950–1975

Sound recording in the British folk revival: ideology, discourse and practice, 1950–1975 Matthew Ord Submitted in fulfilment of the degree of PhD International Centre for Music Studies Newcastle University March 2017 Abstract Although recent work in record production studies has advanced scholarly understandings of the contribution of sound recording to musical and social meaning, folk revival scholarship in Britain has yet to benefit from these insights. The revival’s recording practice took in a range of approaches and contexts including radio documentary, commercial studio productions and amateur field recordings. This thesis considers how these practices were mediated by revivalist beliefs and values, how recording was represented in revivalist discourse, and how its semiotic resources were incorporated into multimodal discourses about music, technology and traditional culture. Chapters 1 and 2 consider the role of recording in revivalist constructions of traditional culture and working class communities, contrasting the documentary realism of Topic’s single-mic field recordings with the consciously avant-garde style of the BBC’s Radio Ballads. The remaining three chapters explore how the sound of recorded folk was shaped by a mutually constitutive dialogue with popular music, with recordings constructing traditional performance as an authentic social practice in opposition to an Americanised studio sound equated with commercial/technological mediation. As the discourse of progressive rock elevated recording to an art practice associated with the global counterculture, however, opportunities arose for the incorporation of rock studio techniques in the interpretation of traditional song in the hybrid genre of folk-rock. Changes in studio practice and technical experiments with the semiotics of recorded sound experiments form the subject of the final two chapters. -

(Sound Off Live 2013 Winner) Indie Soul Meets Jazzy Blues

Artscape Entertainment Resource Guide 2013 Band Name Genre Website Email Phone Number Allie & The Cats (Sound Off Live 2013 Winner) Indie Soul meets Jazzy Blues http://www.alliemariemusic.com [email protected] 4109916973 Balti Mare Balkan Gypsy Brass http://www.facebook.com/baltimare [email protected] 4109633799 Basement Instinct (Sound Off Live 2013 Winner) Alternative Rock https://www.facebook.com/basementinstinctband [email protected] 4437038941 Bearstronaut pop http://bearstronaut.com [email protected] 8609124857 Big Sur Alternative Melodic Rock http://www.bigsurrock.com [email protected] 3015931778 Billy Wilkins Jazz/Rock https://soundcloud.com/billy-wilkins-1 [email protected] 4103696360 Blizz Hip Hop http://www.hulkshare.com/Blizz [email protected] 4439860731 Boozey R&B and Hip Hop http://Boozeyonline.com [email protected] Braunsy Brooks & Worship Kulture Christian http://www.bbworshipkulture.com [email protected] 8284554010 Brittanie Thomas Music Soul/R&B http://www.brittaniethomas.com [email protected] 4433608985 Brothers Kardell Experimental electronic pop metal hip-hop http://www.soundcloud.com/brotherskardell [email protected] 2022862623 Buddah Bass Hip-Hop/Pop http://Buddahbass.bandcamp.com [email protected] 3365779559 Bumpin Uglies Reggae/Ska http://www.bumpinugliesmusic.com [email protected] 4102793613 Children of a Vivid Eden Alternative rock http://www.facebook.com/c.o.v.e.rock [email protected] 4436324130 Chris Reynolds and -

Recent Critical Praise for My Brightest Diamond's This Is My Hand

Recent critical praise for My Brightest Diamond’s This Is My Hand Favorite Songs of 2014 “‘Pressure’: This baroque pop gem opens with drum corps and woodwinds, tacks on a tribal rhythm breakdown and just goes for it. All the way.” “…one of the most powerful and dramatic voices of the past decade.” “…an ability to cultivate intimacy through flawless, complex production with a beating heart.” “As a musician, Worden (who performs as My Brightest Diamond) builds her songs deliberately and impeccably…words are painted, sounds are sculpted, and the nature of Worden’s voice itself adds dimension—more than a single vocalist usually can. Her wholly enveloping, finely tuned alto sounds by turns forceful, vulnerable, cooing, playful, and endlessly emotive.” “…has a feeling for both the grandeur and the grain, building every sweeping gesture in her music out of a swarm of small details.” The Best of 2014 “…added to her smart, savvy chamber pop the influence of funk and marching bands. Her flawless voice pecks, jabs and floats above a world of rhythm that gives the new music its motion and undeniable heartbeat.” “At times, This Is My Hand all but commands listeners to dance.” “On her new album, This Is My Hand, she continues to reach far and wide with great success, adding marching-band rhythms and funky horns to her mix.” “…sounds like a modern-day Nina Simone…” “…This is My Hand works on a visceral level, conjuring Worden’s intended image of tribal, fireside collaboration through a rich diversity of texture, detail, and tone.” “…successful exercise in percussive, jagged art-pop that explores themes of self-acceptance, sensuality, and community.” “...unique and oddly beautiful.” “…presents an invigorating progression of Worden’s sonic palette…” #3: MBE Producer Ariana Morgenstern’s Top Albums of 2014 “…gorgeous new album…” “This Is My Hand is an album I would recommend to anyone—for exactly all the reasons that it’s hard to write about. -

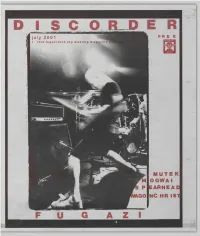

I S C O R D E R Free

I S C O R D E R FREE IUTE K OGWAI ARHEAD NC HR IS1 © "DiSCORDER" 2001 by the Student Radio Society of the University of British Columbia. All rights reserved. Circuldtion 1 7,500. Subscriptions, payable in advance, to Canadian residents are $15 for one year, to residents of the USA are $15 US; $24 CDN elsewhere. Single copies are $2 (to cover postage, of course). Please make cheques or money orders payable to DiSCORDER Mag azine. DEADLINES: Copy deadline for the August issue is July 14th. Ad space is available until July 21st and ccn be booked by calling Maren at 604.822.3017 ext. 3. Our rates are available upon request. DiS CORDER is not responsible for loss, damage, or any other injury to unsolicited mcnuscripts, unsolicit ed drtwork (including but not limited to drawings, photographs and transparencies), or any other unsolicited material. Material can be submitted on disc or in type. As always, English is preferred. Send e-mail to DSCORDER at [email protected]. From UBC to Langley and Squamish to Bellingham, CiTR can be heard at 101.9 fM as well as through all major cable systems in the Lower Mainland, except Shaw in White Rock. Call the CiTR DJ line at 822.2487, our office at 822.301 7 ext. 0, or our news and sports lines at 822.3017 ext. 2. Fax us at 822.9364, e-mail us at: [email protected], visit our web site at http://www.ams.ubc.ca/media/citr or just pick up a goddamn pen and write #233-6138 SUB Blvd., Vancouver, BC. -

BAM Announces Its Bamcafe Live November Music Programming Featuring Jazz, Middle Eastern, Chamber Pop, Baroque Cabaret, and Hip-Hop

Brooklyn 30 Lafayette Avenue Communications Department Academy Brooklyn NY 11217-1486 Sandy Sawotka of Telephone: 718.636.4111 Fatima Kafele Music Fax: 718.857.2021 Jennifer Lam 718.636.4129 [email protected] News Release BAM Announces its BAMcafe Live November Music Programming Featuring Jazz, Middle Eastern, Chamber Pop, Baroque Cabaret, and Hip-Hop Highlights include the NextNext music series showcase, modern jazz arrangements of Bjork's music, the Middle Eastern musical hybrid of Shusmo, chamber pop with Greta Gertler, the jazz fusion of Fred Ho and the Afro Asian Music Ensemble, pop-cabaret with Daniel Isengart, the ukulele/viola sounds of Songs from a Random House, and a Thanksgiving holiday weekend hip-hop extravaganza with Akim Funk Buddha No cover! $10 food/drink minimum, Friday-Saturday BROOKLYN, October 4, 2005-As part of BAM's 2005 Next Wave Festival, BAMcafe Live, the performance series curated by Limor Tomer, presents an eclectic mix of jazz, spoken word, rock, pop, and world beat Friday and Saturday nights. BAMcafe Live events have no cover charge ($1 0 food/drink minimum). For information and updates, call 718.636.4139 or visit www.bam.org. (For press reservations and photos, contact Fatima Kafele at 718.636.4129 x4 or [email protected]). BAMcafe kicks off a month of great music with Travis Sullivan's Bjorkestra (November 4), a group that crafts modem jazz arrangements of Bjork's visionary techno pop. The next night (November 5), Shusmo concludes the NextNext series of talented musicians in their 20s, with an eclectic, Middle Eastern blend of jazz and Latin Rhythms. -

Compound AABA Form and Style Distinction in Heavy Metal *

Compound AABA Form and Style Distinction in Heavy Metal * Stephen S. Hudson NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: hps://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.21.27.1/mto.21.27.1.hudson.php KEYWORDS: Heavy Metal, Formenlehre, Form Perception, Embodied Cognition, Corpus Study, Musical Meaning, Genre ABSTRACT: This article presents a new framework for analyzing compound AABA form in heavy metal music, inspired by normative theories of form in the Formenlehre tradition. A corpus study shows that a particular riff-based version of compound AABA, with a specific style of buildup intro (Aas 2015) and other characteristic features, is normative in mainstream styles of the metal genre. Within this norm, individual artists have their own strategies (Meyer 1989) for manifesting compound AABA form. These strategies afford stylistic distinctions between bands, so that differences in form can be said to signify aesthetic posing or social positioning—a different kind of signification than the programmatic or semantic communication that has been the focus of most existing music theory research in areas like topic theory or musical semiotics. This article concludes with an exploration of how these different formal strategies embody different qualities of physical movement or feelings of motion, arguing that in making stylistic distinctions and identifying with a particular subgenre or style, we imagine that these distinct ways of moving correlate with (sub)genre rhetoric and the physical stances of imagined communities of fans (Anderson 1983, Hill 2016). Received January 2020 Volume 27, Number 1, March 2021 Copyright © 2021 Society for Music Theory “Your favorite songs all sound the same — and that’s okay . -

Download Internet Service Channel Lineup

INTERNET CHANNEL GUIDE DJ AND INTERRUPTION-FREE CHANNELS Exclusive to SiriusXM Music for Business Customers 02 Top 40 Hits Top 40 Hits 28 Adult Alternative Adult Alternative 66 Smooth Jazz Smooth & Contemporary Jazz 06 ’60s Pop Hits ’60s Pop Hits 30 Eclectic Rock Eclectic Rock 67 Classic Jazz Classic Jazz 07 ’70s Pop Hits Classic ’70s Hits/Oldies 32 Mellow Rock Mellow Rock 68 New Age New Age 08 ’80s Pop Hits Pop Hits of the ’80s 34 ’90s Alternative Grunge and ’90s Alternative Rock 70 Love Songs Favorite Adult Love Songs 09 ’90s Pop Hits ’90s Pop Hits 36 Alt Rock Alt Rock 703 Oldies Party Party Songs from the ’50s & ’60s 10 Pop 2000 Hits Pop 2000 Hits 48 R&B Hits R&B Hits from the ’80s, ’90s & Today 704 ’70s/’80s Pop ’70s & ’80s Super Party Hits 14 Acoustic Rock Acoustic Rock 49 Classic Soul & Motown Classic Soul & Motown 705 ’80s/’90s Pop ’80s & ’90s Party Hits 15 Pop Mix Modern Pop Mix Modern 51 Modern Dance Hits Current Dance Seasonal/Holiday 16 Pop Mix Bright Pop Mix Bright 53 Smooth Electronic Smooth Electronic 709 Seasonal/Holiday Music Channel 25 Rock Hits ’70s & ’80s ’70s & ’80s Classic Rock 56 New Country Today’s New Country 763 Latin Pop Hits Contemporary Latin Pop and Ballads 26 Classic Rock Hits ’60s & ’70s Classic Rock 58 Country Hits ’80s & ’90s ’80s & ’90s Country Hits 789 A Taste of Italy Italian Blend POP HIP-HOP 750 Cinemagic Movie Soundtracks & More 751 Krishna Das Yoga Radio Chant/Sacred/Spiritual Music 03 Venus Pop Music You Can Move to 43 Backspin Classic Hip-Hop XL 782 Holiday Traditions Traditional Holiday Music -

Steve Waksman [email protected]

Journal of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music doi:10.5429/2079-3871(2010)v1i1.9en Live Recollections: Uses of the Past in U.S. Concert Life Steve Waksman [email protected] Smith College Abstract As an institution, the concert has long been one of the central mechanisms through which a sense of musical history is constructed and conveyed to a contemporary listening audience. Examining concert programs and critical reviews, this paper will briefly survey U.S. concert life at three distinct moments: in the 1840s, when a conflict arose between virtuoso performance and an emerging classical canon; in the 1910s through 1930s, when early jazz concerts referenced the past to highlight the music’s progress over time; and in the late twentieth century, when rock festivals sought to reclaim a sense of liveness in an increasingly mediatized cultural landscape. keywords: concerts, canons, jazz, rock, virtuosity, history. 1 During the nineteenth century, a conflict arose regarding whether concert repertories should dwell more on the presentation of works from the past, or should concentrate on works of a more contemporary character. The notion that works of the past rather than the present should be the focus of concert life gained hold only gradually over the course of the nineteenth century; as it did, concerts in Europe and the U.S. assumed a more curatorial function, acting almost as a living museum of musical artifacts. While this emphasis on the musical past took hold most sharply in the sphere of “high” or classical music, it has become increasingly common in the popular sphere as well, although whether it fulfills the same function in each realm of musical life remains an open question.