Marketing Dynamics of Thewest Point Foundry, 1817-1911:A Value

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smith Believes Record Justifies Another Term

Roots and Shoots: Bagging the longhorned beetle | See page 15 FRIDAY, AUGUST 2, 2013 69 MAIN ST., COLD SPRING, N.Y. | www.philipstown.info Storm King reigns on a summer’s morning | For more Summer Photofest images see page 16. Photo by Kevin Harrison Smith Believes Record Manitou Properties Seeks to Justifies Another Term Turn Plumbush Restaurant into Sees opponent’s criticisms as not serious Pre-K to Grade 6 School were the crime other events. Located just outside of Cold By Kevin E. Foley numbers flowing Philipstown Spring, on Route 9D at Peekskill and the other way. s an incumbent, Putnam County Planning Board Moffatt Roads, the property is in a Town So Smith has a Sheriff Donald B. Smith would ap- of Philipstown hamlet-mixed use zoning right to lay claim gets site plan pear to have the wind at his back district. Manitou Properties does not yet A to success and as he seeks re-election to a fourth term submission own the site, with completion of the sale he proudly touts in office. According to the New York state dependent on site-plan approval. Putnam’s safety By Liz Schevtchuk Department of Criminal Justice Services, Sheriff Smith Photo by K.E. Foley When it met July 25, the Planning record as the Armstrong Putnam County has ranked number one Board declared the proposal a major primary reason in criminal safety for the last three years local business has begun efforts to project (triggering higher level scrutiny), voters should return him to office. This in a row. -

An Examination of the Technology That Evolved from the Rogers Locomotive & Machine Company, Paterson, NJ

Northeast Historical Archaeology Volume 4 1974 Symposium on Industrial Archaeology, Article 4 Paterson, N.J. 1975 An Examination of the Technology that Evolved from the Rogers Locomotive & Machine Company, Paterson, NJ Ralph J. Leo Follow this and additional works at: http://orb.binghamton.edu/neha Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Leo, Ralph J. (1975) "An Examination of the Technology that Evolved from the Rogers Locomotive & Machine Company, Paterson, NJ," Northeast Historical Archaeology: Vol. 4 4, Article 4. https://doi.org/10.22191/neha/vol4/iss1/4 Available at: http://orb.binghamton.edu/neha/vol4/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Northeast Historical Archaeology by an authorized editor of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. In Examination of the Technology that lvolved from the Rogers Locomotive & Machine OompanJ, Paterson, I.J. Ralph J.Leo IN TROD UCTION when early canals wer'e still under con struction, several pioneers became inter ested in the railroad as the possible Until 1815, the southern agricultural primary transportation source for America plantations, northern iron plantations, (Taylor 1951 : 76). Already, some 100 and small community-oriented sawmills years earlier in Britain, Thomas Savery and gristmills supplied services and pro and Thomas Neucomens bad perfected the ducts on a very small scale (Taylor 1951: modern type of stationary steam engine; 5-6 ). When population increase and in within 50 years it had been improved flux required increased production of steadily and used regularly for power in the basic necessities, horne industry no mining operations. -

WEST POINT FOUNDRY Maker of the Parrott Rifle, Famous Civil War

WEST POINT FOUNDRY Maker of The Parrott Rifle, Famous Civil War Cannon 1 i i WEST POINT FOUNDRY ! The ~a~ol$onicWars demonstrat&d the importance of artillery in modern warfdre. This was brought home to the American people when in the War Of 1812, they found themselves opposed by heavy artillery in the hand8 of seasoned troops, both of which we lacked. The first graduate of West Point Military Academy, General Joseph Swift determined that it would not happen again. He was able to en- list the financial backing of Gouverneur Kemble, willram Kemble and others. In 1818 they organized the West Point Foundry with kstablishments at Cold Spring and New York City. It was necessary to "bootleg" skilled labor out of Europe by way of Ireland. They were able to evade ship pursuit. Their first government demonstration of heavy cannon firing caused some of the cannon to burst. But they were ablt to prove the fault was not in the cannon but In the faulty ammunitiol So, this Foqndry along with three other foundries were subsidized by the government. Success followed their enterprise until it was said,"there was no other foundry like it in America". Prom 50 to 100 heavy ordnance were made each year with the accompanying ammhition. They branched out. Stoves were just becoming popular. Iron pipe replaced wood for water mains in New York and Boston. Machinery for making sugar in South America and the Southern States was in demand. Engines for steamboats and railroads were made. The famous "DeWitt Clinton" railroad engine was built in 1831. -

Butterfield Hospital Phase 1A Literature Review and Sensitivity Analysis

Appendix J Archaeology Phase 1A Report Butterfield Hospital Phase 1A Literature Review and Sensitivity Analysis Paulding Avenue and Route 9D Town of Cold Spring, Putnam County New York Prepared for: Tim Miller Associates. 10 North Street Cold Spring NY By: CITY/SCAPE: Cultural Resource Consultants 166 Hillair Circle White Plains NY 10605 December 2013 BUTTERFIELD HOSPITAL Paulding Avenue and Route 9D Town of Cold Spring, Putnam County, New York TABLE OF CONTENTS Management Summary Map List Phase 1A Literature Review and Sensitivity Analysis Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 Project Area Description ...................................................................................... 1 Environmental Information .................................................................................. 5 Potential for the Site to Contain Prehistoric or Historic Cultural Resources ....... 6 History of the Site ................................................................................................ 6 Butterfield Hospital ........................................................................................... 22 National Register Listed .................................................................................... 25 Additional Research Undertaken ....................................................................... 27 Sensitivity Assessment and Site Prediction ....................................................... 27 Conclusions and Recommendations -

A Geophysical and Archaeological Investigation of the Waterpower System at the West Point Foundry, Cold Spring, New York

Michigan Technological University Digital Commons @ Michigan Tech Dissertations, Master's Theses and Master's Dissertations, Master's Theses and Master's Reports - Open Reports 2004 Waterpower : a geophysical and archaeological investigation of the waterpower system at the West Point Foundry, Cold Spring, New York Kimberly A. Finch Michigan Technological University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/etds Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Copyright 2004 Kimberly A. Finch Recommended Citation Finch, Kimberly A., "Waterpower : a geophysical and archaeological investigation of the waterpower system at the West Point Foundry, Cold Spring, New York", Master's Thesis, Michigan Technological University, 2004. https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/etds/307 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/etds Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons WATERPOWER: A GEOPHYSICAL AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION OF THE WATERPOWER SYSTEM AT THE WEST POINT FOUNDRY, COLD SPRING, NEW YORK. By Kimberly A. Finch A THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN INDUSTRIAL ARCHAEOLOGY MICHIGAN TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY 2004 2004 Finch This thesis, "Waterpower: A Geophysical and Archaeological Investigation of the Waterpower System at the West Point Foundry, Cold Spring, New York" is hereby approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER of SCIENCE IN INDUSTRIAL ARCHAEOLOGY DEPARTMENT: Social Sciences Industrial Archaeology Signatures: Thesis Advisor ______________________________ Dr. Susan Martin Department Chair ______________________________ Dr. Bruce Seely Date ______________________________ Acknowledgements i Acknowledgements I would like to thank the Scenic Hudson Land Trust, Inc. for providing me with the opportunity to work on this project. Special thanks to my advisor, Dr. -

Consumer Identity and Social Stratification in Hacienda La Esperanza, Manatí, Puerto Rico

THE MATERIAL CULTURE OF SLAVERY: CONSUMER IDENTITY AND SOCIAL STRATIFICATION IN HACIENDA LA ESPERANZA, MANATÍ, PUERTO RICO A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Nydia I. Pontón-Nigaglioni December 2018 Examining Committee Members: Paul F. Farnsworth, Advisory Chair, Department of Anthropology Anthony J. Ranere, Department of Anthropology Patricia Hansell, Department of Anthropology Theresa A. Singleton, External Member, University of Syracuse, Anthropology © Copyright 2018 by Nydia I. Pontón-Nigaglioni All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT This dissertation focuses on the human experience during enslavement in nineteenth-century Puerto Rico, one of the last three localities to outlaw the institution of slavery in the Americas. It reviews the history of slavery and the plantation economy in the Caribbean and how the different European regimes regulated slavery in the region. It also provides a literature review on archaeological research carried out in plantation contexts throughout the Caribbean and their findings. The case study for this investigation was Hacienda La Esperanza, a nineteenth- century sugar plantation in the municipality of Manatí, on the north coast of the island. The history of the Manatí Region is also presented. La Esperanza housed one of the largest enslaved populations in Puerto Rico as documented by the slave census of 1870 which registered 152 slaves. The examination of the plantation was accomplished through the implementation of an interdisciplinary approach that combined archival research, field archaeology, anthropological interpretations of ‘material culture’, and geochemical analyses (phosphates, magnetic susceptibility, and organic matter content as determined by loss on ignition). -

Featherstonaugh's Grand Idea

Painting (1906) by E. L. Henry of the early days of railroading in the Mohawk Valley near Little Falls. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Featherstonaugh’s Grand Idea The Early Years of Railroading in Upstate NY The origins of the Empire Corridor lie in the first half the 19th Century when rapid technological change – combining with and accelerating economic and population growth – led to the construction of some of the first railroads in America. The then modern marvel of the Erie Canal had open in 1825, connecting the heartland of the nation with the East Coast. After many proposals dating back to the 18th Century when canoes of traders had to paddle and portage from Lake Ontario and down the Mohawk River, construction started on July 4th, 1817 in the village of Rome. It was by far the greatest engineering project in the young country, costing the gross domestic product of the state to build, the money coming mostly from bonds (a federal loan was sought but denied) sold to domestic and foreign investors. Champion by NYS Governor DeWitt Clinton, the canal scheme had been called “little short of madness” by Thomas Jefferson in 1809, then the US President, who stated that it might be a good idea in a century hence. The grand canal scheme proved so successful that it paid of its construction bonds in ten years, filling to the brim the coffers the state and federal government for some time in canal tolls (state) and trade tariffs (federal) at the port of New York. The canal reached its peak in freight tonnage during the American Civil War, being enlarge serval times during the 19th Century to accommodate the burgeoning traffic and larger barges. -

City Or Town ____North Freedom ______N/A Vicinity State Wisconsin Code WI County Sauk Code 111 Zip Code 53951

NFS Form 10-900 10024-0018 (January 1992) United States Department of Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determination properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the Nati of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Compl item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requeste an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NFS Form 10-900A) . Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Steam Locomotive #1385 other names/site number N/A 2. Location street & number E8948 Diamond Hill Road N/A not for publication city or town ____North Freedom ______ N/A vicinity state Wisconsin code WI county Sauk code 111 zip code 53951 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets __ does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant nationally statewide X locally. ( See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of certifying official/Title y ^ Date Deputy State HistoricvPreservation Qfficer-^I State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property _ meets _ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Indian Point, Units 2 & 3, Phase IA Literature Review And

ENERCON SERVICES, INC. An Employee Owned Company 5100 E. Skelly Drive, Suite 450 Tulsa, OK 74135 (918) 665-7693 (918) 665-7232 - Fax August 21, 2007 Ms. Carol Ash, Commissioner State Historic Preservation Officer New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation Historic Preservation Field Services Bureau Empire State Plaza, Agency Building #1 Albany, NY 12238 RE: Entergy Nuclear Indian Point 2 and Entergy Nuclear Indian Point 3 Phase 1A Literature Review and Archeological Sensitivity Assessment Westchester County, New York Dear Ms. Ash: On behalf of Entergy Nuclear Indian Point 2, LLC and Entergy Nuclear Indian Point 3, LLC (hereafter referred to as "Entergy"), the owner of Indian Point Unit 2 and Indian Point Unit 3, Enercon is forwarding the enclosed Phase 1A Literature Review and Archeological Sensitivity Assessment of the Indian Point site. Entergy has filed an application with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) to renew the Indian Point 2 and Indian Point 3 Operating Licenses for an additional twenty years. A copy of this Phase 1A was submitted to the NRC in response to a License Renewal Site Environmental Audit Additional Information Request. Entergy does not have plans for further development of the property in association with the application for license renewal, but has developed a procedural plan for management of cultural resources ahead of any future ground disturbing activities at the plant. Entergy procedure EN- EV-121 (Cultural Resources ProtectionPlan), which is also enclosed for your information, was developed in an effort to meet state and federal expectations. The measures in this procedure include archeological investigations and consultations with the New York SHPO and appropriate Native American groups ahead of any future ground disturbing activities, as applicable to the ground-disturbing activity. -

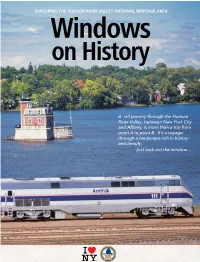

Windows on History

EXPLORING THE HUDSON RIVER VALLEY NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA Windows on History A rail journey through the Hudson River Valley, between New York City and Albany, is more than a trip from point A to point B. It’s a voyage through a landscape rich in history and beauty. Just look out the window… Na lley tion Va al r H e e v r i i t R a g n e o A s r d e u a H Na lley tion Va al r H e e v r i i t R a g n e o A s r d e u a H W ELCOME TO THE HUDSON RIVER VALLEY! RAVELING THROUGH THIS HISTORIC REGION, you will discover the people, places, and events that formed our national identity, and led Congress to designate the Hudson River Valley as a National Heritage Area in 1996. The Hudson River has also been designated one of our country’s Great American Rivers. TAs you journey between New York’s Pennsylvania station and the Albany- Rensselaer station, this guide will interpret the sites and features that you see out your train window, including historic sites that span three centuries of our nation’s history. You will also learn about the communities and cultural resources that are located only a short journey from the various This project was made station stops. possible through a partnership between the We invite you to explore the four million acres Hudson River Valley that make up the Hudson Valley and discover its National Heritage Area rich scenic, historic, cultural, and recreational and I Love NY. -

Slavery, Economic Development, and Modernization on Louisiana Sugar Plantations, 1820-1860

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1997 The uS gar Masters: Slavery, Economic Development, and Modernization on Louisiana Sugar Plantations, 1820-1860. Richard J. Follett Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Follett, Richard J., "The uS gar Masters: Slavery, Economic Development, and Modernization on Louisiana Sugar Plantations, 1820-1860." (1997). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6540. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6540 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text direct^ from the oiigmal or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter fiice; while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The qonlityr of this reprodaction is dependent upon the qnalityr of the copy subm itted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photogr^hs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversety afifect reproductiofL In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, b^inning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing fi*om left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. -

Section 1: Comprehensive Planning Process

Philipstown Comprehensive Plan 2006 CHAPTER 1 / BACKGROUND Section 1: Comprehensive Planning Process This Comprehensive Plan is the product of a five-year process in which the residents of Philipstown came together to agree upon a common vision for their future, and the Comprehensive Plan Special Board shaped that vision into this action-oriented document. Over the five years, numerous meetings and two public hearings were held, giving residents many opportunities to offer and respond to ideas and suggestions. This Plan is the culmination of a significant effort by many citizens of Philipstown working together to express who we are and what we want for our future. Although a professional planning consultant provided assistance, this Plan was written by the community and for the community. The process began when the Town Board commissioned a "diagnostic" planning study of the Town by planning consultant Joel Russell. That study, completed in October, 2000, reviewed the 1991 Town Master Plan, and recommended that the Town prepare a more citizen-based comprehensive plan which would be concise and readable, "a new planning document that clearly expresses a set of shared goals and principles." The first step in developing this plan was a town-wide forum bringing a cross-section of the community together to define consensus goals and action strategies to accomplish them. This forum, Philipstown 2020, was held over two and a half days in April, 2001. More than two hundred residents participated. "Philipstown 2020: A Synthesis" (see Appendix A) expresses the outcome of this forum, and its goals were the starting point for preparing this Plan.