World War II at the Ponce De Leon Inlet Light Station

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Safe Boating Through the St. Lucie Inlet

Information: Florida Fish & Wildlife Commission 850-488-4676 SAFE BOATING US Coast Guard - Ft. Pierce 772-461-7606 THROUGH THE ST. LUCIE INLET US Coast Guard Auxiliary 772-465-8128 US Army Corps of Engineers 772-221-3349 St. Lucie Inlet Coastal 772-225-2300 Weather Station HERE ARE SOME THINGS TO REMEMBER: • Listen to the most recent weather forecast for the times you plan to go out AND come back in the inlet. • Look in the Tide Tables or local newspapers for the times St. Lucie Inlet of predicted high and low tides for the day you plan to go out. Remember the outgoing (ebb) tital current at low Newcomers tide is the worst time to make a passage through the St. Lucie Inlet. If you are a boater new to this area, it is highly • Safe boating practices are even more important in inlets. recommended that you make your first passage of Check your boat before you head out. Life preservers the St. Lucie Inlet as an observer. An experienced should be worn when going through inlets. boater with local knowledge at the helm can point • Expect the unexpected. Watch the clouds to anticipate out various hazards and conditions to avoid. This is severe weather such as thunderstorms. Be on the lookout for shifting shoals and changing channels. especially important if you have no prior experience • Engine failure is common in small boats in rough seas. with any ocean inlets. The extra roughness agitates gasoline and settled dirt or water in the fuel system, which can cause engine failure Notes on Navigation at Night at a crtical time. -

1 the Influence of Groyne Fields and Other Hard Defences on the Shoreline Configuration

1 The Influence of Groyne Fields and Other Hard Defences on the Shoreline Configuration 2 of Soft Cliff Coastlines 3 4 Sally Brown1*, Max Barton1, Robert J Nicholls1 5 6 1. Faculty of Engineering and the Environment, University of Southampton, 7 University Road, Highfield, Southampton, UK. S017 1BJ. 8 9 * Sally Brown ([email protected], Telephone: +44(0)2380 594796). 10 11 Abstract: Building defences, such as groynes, on eroding soft cliff coastlines alters the 12 sediment budget, changing the shoreline configuration adjacent to defences. On the 13 down-drift side, the coastline is set-back. This is often believed to be caused by increased 14 erosion via the ‘terminal groyne effect’, resulting in rapid land loss. This paper examines 15 whether the terminal groyne effect always occurs down-drift post defence construction 16 (i.e. whether or not the retreat rate increases down-drift) through case study analysis. 17 18 Nine cases were analysed at Holderness and Christchurch Bay, England. Seven out of 19 nine sites experienced an increase in down-drift retreat rates. For the two remaining sites, 20 retreat rates remained constant after construction, probably as a sediment deficit already 21 existed prior to construction or as sediment movement was restricted further down-drift. 22 For these two sites, a set-back still evolved, leading to the erroneous perception that a 23 terminal groyne effect had developed. Additionally, seven of the nine sites developed a 24 set back up-drift of the initial groyne, leading to the defended sections of coast acting as 1 25 a hard headland, inhabiting long-shore drift. -

A Nonlinear Relationship Between Marsh Size and Sediment Trapping Capacity Compromises Salt Marshes’ Stability Carmine Donatelli1*, Xiaohe Zhang2*, Neil K

https://doi.org/10.1130/G47131.1 Manuscript received 22 October 2019 Revised manuscript received 9 March 2020 Manuscript accepted 26 April 2020 © 2020 The Authors. Gold Open Access: This paper is published under the terms of the CC-BY license. Published online 10 June 2020 A nonlinear relationship between marsh size and sediment trapping capacity compromises salt marshes’ stability Carmine Donatelli1*, Xiaohe Zhang2*, Neil K. Ganju3, Alfredo L. Aretxabaleta3, Sergio Fagherazzi2† and Nicoletta Leonardi1† 1 Department of Geography and Planning, School of Environmental Sciences, Faculty of Science and Engineering, University of Liverpool, Roxby Building, Chatham Street, Liverpool L69 7ZT, UK 2 Department of Earth Sciences, Boston University, 675 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts 02215, USA 3 Woods Hole Coastal and Marine Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey, Woods Hole, Massachusetts 02543, USA ABSTRACT tidal flats to keep pace with sea-level rise (Mari- Global assessments predict the impact of sea-level rise on salt marshes with present-day otti and Fagherazzi, 2010). levels of sediment supply from rivers and the coastal ocean. However, these assessments do Regional effects are crucial when evaluating not consider that variations in marsh extent and the related reconfiguration of intertidal area coastal interventions under the management of affect local sediment dynamics, ultimately controlling the fate of the marshes themselves. multiple agencies. Though many studies have We conducted a meta-analysis of six bays along the United States East Coast to show that focused on local marsh dynamics, less atten- a reduction in the current salt marsh area decreases the sediment availability in estuarine tion has been paid to how changes in marsh systems through changes in regional-scale hydrodynamics. -

A Revisit to a Lightkeeper's Home

A REVISIT TO A LIGHTKEEPER'S HOME It was an isolated place wh ere th e kids would dash to the fla gpole to dip the insigne in salute when a yacht or ship passed the lighthouse station and re ceived a returning toot. The air was clean, the water cyrstal clear, game and fish sufficient to f eed thefamilies, remote, but not a "lonely place" as some p eople may believe. Three dau ght ers of former lighthouse keepers retu rn to By Hibb ard Casselb erry, Jr. the station for a visit in 1976. They are, from left to right, Ruth Isler Hedden, Mary Knight Voss, and lora Driving north on AlA from Pomp ano Beach to Isler Saxon. the Hillsboro Inlet and the lighthouse station on its north shore, three daughters of former lighthouse Hibbard Casselberry, Jr.. is an architectural de keepers re me mbered that the road was not always signer and planner. a certified building inspector, so smooth nor congested. Zora Isler Saxon, sitting and a construction specification writer. He has next to her younger sister, Ruth Isler Hedden, served as editorfor several trade publications and said, "Part of it was an awful road, with sharp has written extens ively on gen ealogy . white gravel." Mary Knight Voss remembered, "The Beach Road (Atlantic Blvd .) in the early 1920s was only a gravel road to the bea ch area and the road north In the late 1800s, the south part of Florida's (AlA) was a ru tted sa nd road that ended here at peninsula was very sparsely populated. -

November 2020

South Brevard Historical Society, Inc. Founded 1966 E Newsletter NOVEMBER 2020 DEAR MEMBERS AND FRIENDS, This month provides two opportunities to celebrate Our Nation. The first, our opportunity to vote in the presidential election of 2020. As we await the final, end of all votes counted, tally I am reminded of a Yogi Bera quote, “it ain’t over til it’s over”. (I did fact check that and it was credited to his words of encouragement to the Mets in the 1973 pennant race.) The origin of another phrase that came to mind seems forgotten in time but I suspect is echoed by many, “it’s all over but the shouting.” The quote that is my prayer and hope for our country is from the poem “America the Beautiful” by Katherine Lee Bates……”and crown thy good wth brotherhood from sea to shining sea”. May we remember that we are the UNITED States and let us “move on.com”. November also provides VETERANS DAY a special time to honor all who have served in the military. Originally called Armistice Day, the holiday celebrated the agreement to end the fighting of WWI on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month in 1918. Following WWII and the Korean War, the name was changed to Veterans Day and the purpose expanded in the U.S. to honor all who serve in the military. During this “time of difficulty” many of us have begun to research and write our family histories. So, it is appropriate that our special feature this month is an essay written in 2008, the 90 th anniversary of the end of WWI, by SBHS board member Nancy Grout about her grandfather, Sidney Emerson Grout, a veteran of WWI. -

Street Names - in Alphabetical Order

Street Names - In Alphabetical Order District / MC-ID NO. Street Name Location County Area Aalto Place Sumter - Unit 692 (Villa San Antonio) 1 Sumter County Abaco Path Sumter - Unit 197 9 Sumter County Abana Path Sumter - Unit 206 9 Sumter County Abasco Court Sumter - Unit 821 (Mangrove Villas) 8 Sumter County Abbeville Loop Sumter - Unit 80 5 Sumter County Abbey Way Sumter - Unit 164 8 Sumter County Abdella Way Sumter - Unit 180 9 Sumter County Abdella Way Sumter - Unit 181 9 Sumter County Abel Place Sumter - Unit 195 10 Sumter County Aber Lane Sumter - Unit 967 (Ventura Villas) 10 Sumter County SE 84TH Abercorn Court Marion - Unit 45 4 Marion County Abercrombie Way Sumter - Unit 98 5 Sumter County Aberdeen Run Sumter - Unit 139 7 Sumter County Abernethy Place Sumter - Unit 99 5 Sumter County Abner Street Sumter - Unit 130 6 Sumter County Abney Avenue VOF - Unit 8 12 Sumter County Abordale Lane Sumter - Unit 158 8 Sumter County Acorn Court Sumter - Unit 146 7 Sumter County Acosta Court Sumter - Unit 601 (Villa De Leon) 2 Sumter County Adair Lane Sumter - Unit 818 (Jacaranda Villas) 8 Sumter County Adams Lane Sumter - Unit 105 6 Sumter County Adamsville Avenue VOF - Unit 13 12 Sumter County Addison Avenue Sumter - Unit 37 3 Sumter County Adeline Way Sumter - Unit 713 (Hillcrest Villas) 7 Sumter County Adelphi Avenue Sumter - Unit 151 8 Sumter County Adler Court Sumter - Unit 134 7 Sumter County Adriana Way Sumter - Unit 711 (Adriana Villas) 7 Sumter County Adrienne Way Sumter - Unit 176 9 Sumter County Adrienne Way Sumter - Unit 949 (Megan -

Rocky Intertidal, Mudflats and Beaches, and Eelgrass Beds

Appendix 5.4, Page 1 Appendix 5.4 Marine and Coastline Habitats Featured Species-associated Intertidal Habitats: Rocky Intertidal, Mudflats and Beaches, and Eelgrass Beds A swath of intertidal habitat occurs wherever the ocean meets the shore. At 44,000 miles, Alaska’s shoreline is more than double the shoreline for the entire Lower 48 states (ACMP 2005). This extensive shoreline creates an impressive abundance and diversity of habitats. Five physical factors predominantly control the distribution and abundance of biota in the intertidal zone: wave energy, bottom type (substrate), tidal exposure, temperature, and most important, salinity (Dethier and Schoch 2000; Ricketts and Calvin 1968). The distribution of many commercially important fishes and crustaceans with particular salinity regimes has led to the description of “salinity zones,” which can be used as a basis for mapping these resources (Bulger et al. 1993; Christensen et al. 1997). A new methodology called SCALE (Shoreline Classification and Landscape Extrapolation) has the ability to separate the roles of sediment type, salinity, wave action, and other factors controlling estuarine community distribution and abundance. This section of Alaska’s CWCS focuses on 3 main types of intertidal habitat: rocky intertidal, mudflats and beaches, and eelgrass beds. Tidal marshes, which are also intertidal habitats, are discussed in the Wetlands section, Appendix 5.3, of the CWCS. Rocky intertidal habitats can be categorized into 3 main types: (1) exposed, rocky shores composed of steeply dipping, vertical bedrock that experience high-to- moderate wave energy; (2) exposed, wave-cut platforms consisting of wave-cut or low-lying bedrock that experience high-to-moderate wave energy; and (3) sheltered, rocky shores composed of vertical rock walls, bedrock outcrops, wide rock platforms, and boulder-strewn ledges and usually found along sheltered bays or along the inside of bays and coves. -

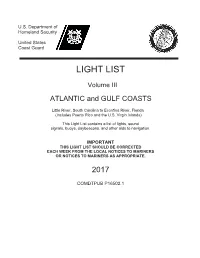

USCG Light List

U.S. Department of Homeland Security United States Coast Guard LIGHT LIST Volume III ATLANTIC and GULF COASTS Little River, South Carolina to Econfina River, Florida (Includes Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands) This /LJKW/LVWFRQWDLQVDOLVWRIOLJKWV, sound signals, buoys, daybeacons, and other aids to navigation. IMPORTANT THIS /,*+7/,67 SHOULD BE CORRECTED EACH WEEK FROM THE LOCAL NOTICES TO MARINERS OR NOTICES TO MARINERS AS APPROPRIATE. 2017 COMDTPUB P16502.1 C TES O A A T S T S G D U E A T U.S. AIDS TO NAVIGATION SYSTEM I R N D U 1790 on navigable waters except Western Rivers LATERAL SYSTEM AS SEEN ENTERING FROM SEAWARD PORT SIDE PREFERRED CHANNEL PREFERRED CHANNEL STARBOARD SIDE ODD NUMBERED AIDS NO NUMBERS - MAY BE LETTERED NO NUMBERS - MAY BE LETTERED EVEN NUMBERED AIDS PREFERRED RED LIGHT ONLY GREEN LIGHT ONLY PREFERRED CHANNEL TO CHANNEL TO FLASHING (2) FLASHING (2) STARBOARD PORT FLASHING FLASHING TOPMOST BAND TOPMOST BAND OCCULTING OCCULTING GREEN RED QUICK FLASHING QUICK FLASHING ISO ISO GREEN LIGHT ONLY RED LIGHT ONLY COMPOSITE GROUP FLASHING (2+1) COMPOSITE GROUP FLASHING (2+1) 9 "2" R "8" "1" G "9" FI R 6s FI R 4s FI G 6s FI G 4s GR "A" RG "B" LIGHT FI (2+1) G 6s FI (2+1) R 6s LIGHTED BUOY LIGHT LIGHTED BUOY 9 G G "5" C "9" GR "U" GR RG R R RG C "S" N "C" N "6" "2" CAN DAYBEACON "G" CAN NUN NUN DAYBEACON AIDS TO NAVIGATION HAVING NO LATERAL SIGNIFICANCE ISOLATED DANGER SAFE WATER NO NUMBERS - MAY BE LETTERED NO NUMBERS - MAY BE LETTERED WHITE LIGHT ONLY WHITE LIGHT ONLY MORSE CODE FI (2) 5s Mo (A) RW "N" RW RW RW "N" Mo (A) "A" SP "B" LIGHTED MR SPHERICAL UNLIGHTED C AND/OR SOUND AND/OR SOUND BR "A" BR "C" RANGE DAYBOARDS MAY BE LETTERED FI (2) 5s KGW KWG KWB KBW KWR KRW KRB KBR KGB KBG KGR KRG LIGHTED UNLIGHTED DAYBOARDS - MAY BE LETTERED WHITE LIGHT ONLY SPECIAL MARKS - MAY BE LETTERED NR NG NB YELLOW LIGHT ONLY FIXED FLASHING Y Y Y "A" SHAPE OPTIONAL--BUT SELECTED TO BE APPROPRIATE FOR THE POSITION OF THE MARK IN RELATION TO THE Y "B" RW GW BW C "A" N "C" Bn NAVIGABLE WATERWAY AND THE DIRECTION FI Bn Bn Bn OF BUOYAGE. -

Exploring Space

EXPLORING SPACE: Opening New Frontiers Past, Present, and Future Space Launch Activities at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station and NASA’s John F. Kennedy Space Center EXPLORING SPACE: OPENING NEW FRONTIERS Dr. Al Koller COPYRIGHT © 2016, A. KOLLER, JR. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without the written consent of the copyright holder Library of Congress Control Number: 2016917577 ISBN: 978-0-9668570-1-6 e3 Company Titusville, Florida http://www.e3company.com 0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Foreword …………………………………………………………………………2 Dedications …………………………………………………………………...…3 A Place of Canes and Reeds……………………………………………….…4 Cape Canaveral and The Eastern Range………………………………...…7 Early Missile Launches ...……………………………………………….....9-17 Explorer 1 – First Satellite …………………….……………………………...18 First Seven Astronauts ………………………………………………….……20 Mercury Program …………………………………………………….……23-27 Gemini Program ……………………………………………..….…………….28 Air Force Titan Program …………………………………………………..29-30 Apollo Program …………………………………………………………....31-35 Skylab Program ……………………………………………………………….35 Space Shuttle Program …………………………………………………..36-40 Evolved Expendable Launch Program ……………………………………..41 Constellation Program ………………………………………………………..42 International Space Station ………………………………...………………..42 Cape Canaveral Spaceport Today………………………..…………………43 ULA – Atlas V, Delta IV ………………………………………………………44 Boeing X-37B …………………………………………………………………45 SpaceX Falcon 1, Falcon 9, Dragon Capsule .………….........................46 Boeing CST-100 Starliner …………………………………………………...47 Sierra -

Driver Charged After Car Gets Stuck in Sand Brevard Schools Earn

TITUSVILLE • MIMS COCOA THE CAPE NORTH BREVARD PORT ST JOHN MERRITT ISLAND COCOA BEACH Vol. 13, No. 27 www.HometownNewsBrevard.com Friday, July 14, 2017 FLYING HIGH FUN FOR ALL CUTIE ALERT! The Henson's bring us Surfisde Playhouse Meet LilBit, our pet of with them to an air force has fun events for all the week! base in Washington. this summer. TOURING WITH THE TOWNIES 14 ENTERTAINMENT 15 PET OF THE WEEK 12 American Made Falcon 9 flies again Brevard schools • Lifetime Warranty • Over 20 colors available earn ‘A’ grade By Austin Rushnell [email protected] BREVARD COUNTY – One of the most significant factors in determining the autonomy of a person is education, Even against salty air and here in the United States, that starts with quality schooling from public insti- tutes. This summer, Brevard Public Schools Alex Schierholtz/staff photographer earned an ‘A’ grade for excellence in edu- A SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket lifts off from Launch Complex 39A at Kennedy cation, earning the district the No. 2 spot Space Center on July 5, carrying its heaviest payload to date: an Intelsat 35e among Florida’s 14 large districts. satellite. Manufactured by Boeing and equipped with an advanced digital “Improvement in our schools is always something to celebrate,” BPS Superinten- payload, Intelsat 35e will deliver high-performance services for wireless dent Desmond Blackburn said in a state- infrastructure, mobility, broadband, government and media customers in ment. “When I consider the great diversi- the Americas, the Caribbean, Europe and Africa. ty in our student population, the relatively 1220 Ridgewood Ave. -

Recent Observations at the Base of the Alaska Peninsula

242 SHORT COMMUNICATIONS RECENT OBSERVATIONS AT THE The only other record was of three in Iliuk Arm, BASE OF THE ALASKA PENINSULA Naknek Lake, Katmai NM, 11 August 1968. Two of the latter were in breeding plumage. DANIEL D. GIBSON Whimbrel. Numenius phueopus. Gabrielson and Lincoln (1959) cite four records of the Whimbrel P.O. Box I.551 for the Bristol Bay area, and Cahalane (1944) records Fairbanks, Alaska 99701 the species once on Naknek River. The following ob- servations of transients on the Monument coast are During May-September 1966, February-September included: eight at Kashvik Bay on 6 May 1967, 1967, and May-September 1968, I was employed 11 at Katmai Bay on 9 May 1967, and 29 at Katmai by the National Park Service (NPS ), U.S. Depart- Bay on 11 May 1967 (one flock of 27). ment of Interior, at Katmai National Monument Lesser Yellowlegs. Totanus fZuvipes. The only (NM), Alaska. A number of significant occurrences previous record of the Lesser Yellowlegs for this of avian species were recorded during this time, de- region is that of Cahalane (1944) for Naknek River. tails of which are given below. All observations are I watched one on 1 July 1968 at Brooks River being my own unless otherwise indicated; no specimens were chased repeatedly by resident Greater Yellowlegs collected. (T. melunoleucus) that were defending several large Red-faced Cormorant. PhuZucrocor~x u&e. On 28 young. The Lesser Yellowlegs called once, and the June 1967 I found 10 pairs of Red-faced Cormorants size difference was noted. breeding among 80 pairs of Pelagic Cormorants (P. -

A Controlled Stable Tidal Inlet at Cartagena De Indias, Colombia Environment Ronald Moor, Marion Van Maren and Cees Van Laarhoven

A Controlled Stable Tidal Inlet at Cartagena de Indias, Colombia Environment Ronald Moor, Marion van Maren and Cees van Laarhoven A Controlled Stable Tidal Inlet at Cartagena de Indias, Colombia Abstract fund the wars fought by the Spanish Crown. The Spanish conquistador’s selected Cartagena for its Since the inception of Cartagena de Indias, Colombia as strategic geographic position and for the natural a Spanish colony, its sewerage was dumped into the protection from raids by British, French and Dutch nearby bodies of water. Not so surprisingly, the growth pirates offered by the surrounding bodies of water of population was marked by growth in sewerage and (see Figure 1). by 1980 60% of the city’s sewerage was dumped on the Ciénaga de la Virgen, a shallow coastal lagoon of Since the city’s inception its sewerage was dumped some 22 km2, and 10 km canals surrounding and into these bodies of water. As the volume of sewerage traversing the city. Whilst the bodies of water could increased in tandem with the growth of the population, absorb the sewerage dumped in the early days, by the part of the city’s sewerage was collected and dumped 1980s the pollution level had become unbearable. by marine outfall into the bay of Cartagena. This began Continuous strong odors attracting mosquitoes, eutro- about 1960. By 1980 however 60% of the city’s phication, and fish death became recurrent events. sewerage was dumped on the Ciénaga de la Virgen, a shallow coastal lagoon of some 22 km2, and 10 km In 1988 the Colombian Planning Department requested canals surrounding and traversing the city.