Rivette and Strong Sensations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feature Films

FEATURE FILMS NEW BERLINALE 2016 GENERATION CANNES 2016 OFFICIAL SELECTION MISS IMPOSSIBLE SPECIAL MENTION CHOUF by Karim Dridi SPECIAL SCREENING by Emilie Deleuze TIFF KIDS 2016 With: Sofian Khammes, Foued Nabba, Oussama Abdul Aal With: Léna Magnien, Patricia Mazuy, Philippe Duquesne, Catherine Hiegel, Alex Lutz Chouf: It means “look” in Arabic but it is also the name of the watchmen in the drug cartels of Marseille. Sofiane is 20. A brilliant Some would say Aurore lives a boring life. But when you are a 13 year- student, he comes back to spend his holiday in the Marseille ghetto old girl, and just like her have an uncompromising way of looking where he was born. His brother, a dealer, gets shot before his eyes. at boys, school, family or friends, life takes on the appearance of a Sofiane gives up on his studies and gets involved in the drug network, merry psychodrama. Especially with a new French teacher, the threat ready to avenge him. He quickly rises to the top and becomes the of being sent to boarding school, repeatedly falling in love and the boss’s right hand. Trapped by the system, Sofiane is dragged into a crazy idea of going on stage with a band... spiral of violence... AGAT FILMS & CIE / FRANCE / 90’ / HD / 2016 TESSALIT PRODUCTIONS - MIRAK FILMS / FRANCE / 106’ / HD / 2016 VENICE FILM FESTIVAL 2016 - LOCARNO 2016 HOME by Fien Troch ORIZZONTI - BEST DIRECTOR AWARD THE FALSE SECRETS OFFICIAL SELECTION TIFF PLATFORM 2016 by Luc Bondy With: Sebastian Van Dun, Mistral Guidotti, Loic Batog, Lena Sukjkerbuijk, Karlijn Sileghem With: Isabelle Huppert, Louis Garrel, Bulle Ogier, Yves Jacques Dorante, a penniless young man, takes on the position of steward at 17-year-old Kevin, sentenced for violent behavior, is just let out the house of Araminte, an attractive widow whom he secretly loves. -

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum Rivette: Texts and Interviews (editor, 1977) Orson Welles: A Critical View, by André Bazin (editor and translator, 1978) Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980) Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983) Midnight Movies (with J. Hoberman, 1983) Greed (1991) This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (editor, 1992) Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995) Movies as Politics (1997) Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970 (coedited with Bill Krohn, 1999) Dead Man (2000) Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000) Abbas Kiarostami (with Mehrmax Saeed-Vafa, 2003) Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (coedited with Adrian Martin, 2003) Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) Discovering Orson Welles (2007) The Unquiet American: Trangressive Comedies from the U.S. (2009) Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Film Culture in Transition Jonathan Rosenbaum the university of chicago press | chicago and london Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for many periodicals (including the Village Voice, Sight and Sound, Film Quarterly, and Film Comment) before becoming principal fi lm critic for the Chicago Reader in 1987. Since his retirement from that position in March 2008, he has maintained his own Web site and continued to write for both print and online publications. His many books include four major collections of essays: Placing Movies (California 1995), Movies as Politics (California 1997), Movie Wars (a cappella 2000), and Essential Cinema (Johns Hopkins 2004). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. -

Eric Rohmer's Film Theory (1948-1953)

MARCO GROSOLI FILM THEORY FILM THEORY ERIC ROHMER’S FILM THEORY (1948-1953) IN MEDIA HISTORY IN MEDIA HISTORY FROM ‘ÉCOLE SCHERER’ TO ‘POLITIQUE DES AUTEURS’ MARCO GROSOLI ERIC ROHMER’S FILM THEORY ROHMER’S ERIC In the 1950s, a group of critics writing MARCO GROSOLI is currently Assistant for Cahiers du Cinéma launched one of Professor in Film Studies at Habib Univer- the most successful and influential sity (Karachi, Pakistan). He has authored trends in the history of film criticism: (along with several book chapters and auteur theory. Though these days it is journal articles) the first Italian-language usually viewed as limited and a bit old- monograph on Béla Tarr (Armonie contro fashioned, a closer inspection of the il giorno, Bébert 2014). hundreds of little-read articles by these critics reveals that the movement rest- ed upon a much more layered and in- triguing aesthetics of cinema. This book is a first step toward a serious reassess- ment of the mostly unspoken theoreti- cal and aesthetic premises underlying auteur theory, built around a recon- (1948-1953) struction of Eric Rohmer’s early but de- cisive leadership of the group, whereby he laid down the foundations for the eventual emergence of their full-fledged auteurism. ISBN 978-94-629-8580-3 AUP.nl 9 789462 985803 AUP_FtMh_GROSOLI_(rohmer'sfilmtheory)_rug16.2mm_v02.indd 1 07-03-18 13:38 Eric Rohmer’s Film Theory (1948-1953) Film Theory in Media History Film Theory in Media History explores the epistemological and theoretical foundations of the study of film through texts by classical authors as well as anthologies and monographs on key issues and developments in film theory. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

Paradoxes of the Nouvelle Vague

ARTICLES · Cinema Comparat/ive Cinema · Vol. I · No. 2. · 2013 · 77-82 Paradoxes of the Nouvelle Vague Marcos Uzal ABSTRACT This essay begins at the start of the magazine Cahiers du cinéma and with the film-making debut of five of its main members: François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, Eric Rohmer, Jacques Rivette and Jean-Luc Godard. At the start they have shared approaches, tastes, passions and dislikes (above all, about a group of related film-makers from so-called ‘classical cinema’). Over the course of time, their aesthetic and political positions begin to divide them, both as people and in terms of their work, until they reach a point where reconciliation is not posible between the ‘midfield’ film-makers (Truffaut and Chabrol) and the others, who choose to control their conditions or methods of production: Rohmer, Rivette and Godard. The essay also proposes a new view of work by Rivette and Godard, exploring a relationship between their interest in film shoots and montage processes, and their affinities with various avant-gardes: early Russian avant-garde in Godard’s case and in Rivette’s, 1970s American avant-gardes and their European translation. KEYWORDS Nouvelle Vague, Jean-Luc Godard, Jacques Rivette, Eric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol, François Truffaut, radical, politics, aesthetics, montage. 77 PARADOXES OF THE NOUVELLE VAGUE In this essay the term ‘Nouvelle Vague’ refers that had emerged from it: they considered that specifically to the five film-makers in this group cinematic form should be explored as a kind who emerged from the magazine Cahiers du of contraband, using the classic art of mise-en- cinéma: Eric Rohmer, Jacques Rivette, Jean-Luc scène rather than a revolutionary or modernist Godard, Claude Chabrol and François Truffaut. -

Pression” Be a Fair Description?

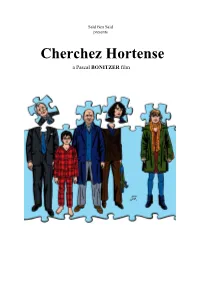

Saïd Ben Saïd presents Cherchez Hortense a Pascal BONITZER film Saïd Ben Saïd presents Cherchez Hortense A PASCAL BONITZER film Screenplay, adaptation and dialogues by AGNÈS DE SACY and PASCAL BONITZER with JEAN-PIERRE BACRI ISABELLE CARRÉ KRISTIN SCOTT THOMAS with the participation of CLAUDE RICH 1h40 – France – 2012 – SR/SRD – SCOPE INTERNATIONAL PR INTERNATIONAL SALES Magali Montet Saïd Ben Saïd Tel : +33 6 71 63 36 16 [email protected] [email protected] Delphine Mayele Tel : +33 6 60 89 85 41 [email protected] SYNOPSIS Damien is a professor of Chinese civilization who lives with his wife, Iva, a theater director, and their son Noé. Their love is mired in a mountain of routine and disenchantment. To help keep Zorica from getting deported, Iva gets Damien to promise he’ll go to his father, a state department official, for help. But Damien and his father have a distant and cool relationship. And this mission is a risky business which will send Damien spiraling downward and over the edge… INTERVIEW OF PASCAL BONITZER Like your other heroes (a philosophy professor, a critic, an editor), Damien is an intellectual. Why do you favor that kind of character? I know, that is seriously frowned upon. What can I tell you? I am who I am and my movies are also just a tiny bit about myself, though they’re not autobiographical. It’s not that I think I’m so interesting, but it is a way of obtaining a certain sincerity or authenticity, a certain psychological truth. Why do you make comedies? Comedy is the tone that comes naturally to me, that’s all. -

Où Va France 2 ?

Sophie Bramly La fondatrice du site Secondsexe.com, dédié au plaisir féminin, produit une collection de courts métrages pour 1 Canal+. Portrait. PAGE 4 Mesrine A l’occasion de la sortie en salles de « L’Instinct de mort », TV&Radio retour sur le parcours Du lundi 20 octobre de l’ex-ennemi public n˚1. PAGE 23 au dimanche 26 octobre Où va France 2 ? Dirty Sexy Money Casting prestigieux pour cette série américaine politiquement incorrecte qui débarque sur Canal+. PAGE 19 L’expédition RTL La station lance une série de grands reportages sur l’état de la planète. Première Audience destination : l’Alaska. PAGE 35 en baisse et nouveaux magazines bâclés, la chaîne vit une rentrée délicate. PAGES 2 ET 3 Dessin de Sylvie Serprix ; Michel Monteaux pour « Le Monde » ; La Petite Reine ; ABC ; RTL. - CAHIER DU « MONDE » DATÉ DIMANCHE 19 - LUNDI 20 OCTOBRE 2008, Nº 19823. NE PEUT ÊTRE VENDU SÉPARÉMENT - 2 Le Monde Dimanche 19 - Lundi 20 octobre 2008 DOSSIER Une prérentrée tumultueuse pour France 2 Bousculée par la suppression de la publicité après 20 heures annoncée pour le 5 janvier 2009, la chaîne amiral de France Télévisions a enregistré en septembre sa plus faible audience. Tandis que la plupart des nouveaux magazines, mis à l’antenne dans la précipitation, n’ont pas convaincu le public RANCE 2 «à la Courbet en remplacement de Lau- 31 octobre. Au-delà, Patrice Duha- peine ». « Vendredi rent Ruquier pour animer la case mel, parle de « changements noir » pour France 2. de l’avant-« JT» ? « Service maxi- lourds » pour une émission « qui « Dérapage » dans le mum », le magazine de consom- n’a pas tenu ses promesses ». -

Classic Frenchfilm Festival

Three Colors: Blue NINTH ANNUAL ROBERT CLASSIC FRENCH FILM FESTIVAL Presented by March 10-26, 2017 Sponsored by the Jane M. & Bruce P. Robert Charitable Foundation A co-production of Cinema St. Louis and Webster University Film Series ST. LOUIS FRENCH AND FRANCOPHONE RESOURCES WANT TO SPEAK FRENCH? REFRESH YOUR FRENCH CULTURAL KNOWLEDGE? CONTACT US! This page sponsored by the Jane M. & Bruce P. Robert Charitable Foundation in support of the French groups of St. Louis. Centre Francophone at Webster University An organization dedicated to promoting Francophone culture and helping French educators. Contact info: Lionel Cuillé, Ph.D., Jane and Bruce Robert Chair in French and Francophone Studies, Webster University, 314-246-8619, [email protected], facebook.com/centrefrancophoneinstlouis, webster.edu/arts-and-sciences/affiliates-events/centre-francophone Alliance Française de St. Louis A member-supported nonprofit center engaging the St. Louis community in French language and culture. Contact info: 314-432-0734, [email protected], alliancestl.org American Association of Teachers of French The only professional association devoted exclusively to the needs of French teach- ers at all levels, with the mission of advancing the study of the French language and French-speaking literatures and cultures both in schools and in the general public. Contact info: Anna Amelung, president, Greater St. Louis Chapter, [email protected], www.frenchteachers.org Les Amis (“The Friends”) French Creole heritage preservationist group for the Mid-Mississippi River Valley. Promotes the Creole Corridor on both sides of the Mississippi River from Ca- hokia-Chester, Ill., and Ste. Genevieve-St. Louis, Mo. Parts of the Corridor are in the process of nomination for the designation of UNESCO World Heritage Site through Les Amis. -

L'amica Delle Rondini. Marilù Parolini Dalla Scena Al Ricordo

Corso di Laurea magistrale interclasse (ordinamento ex D.M. 270/2004) in Musicologia e scienze dello spettacolo (classe LM-45/ LM-46) Tesi di Laurea L’amica delle rondini. Marilù Parolini dalla scena al ricordo. Memorie e visioni di cinema e fotografia. Relatore Ch. Prof. Fabrizio Borin Correlatrice Ch. Prof.ssa Valentina Bonifacio Laureanda Irene Pozzi Matricola 786414 Anno Accademico 2011 / 2012 sessione straordinaria 1 Le cose sono là che navigano nella luce, escono dal vuoto per aver luogo ai nostri occhi. Noi siamo implicati nel loro apparire e scomparire, quasi che fossimo qui proprio per questo. Il mondo esterno ha bisogno che lo osserviamo e raccontiamo, per avere esistenza. E quando un uomo muore porta con sé le apparizioni venute a lui fin dall’infanzia, lasciando agli altri fiutare il buco dove ogni cosa scompare. Gianni Celati1 1 Gianni Celati, Verso la foce, Feltrinelli, Milano, 1988. 2 Indice Introduzione……………………………………………………………..7 1. L’intervista………………………………………………………………10 1.1 L’amica delle rondini. La realizzazione del documentario…….10 1.1.1 Il progetto……………………………………………………………...11 1.1.2 Le riprese……………………………………………………………….12 1.1.3 La fase di montaggio e gli inserti tratti da film…………………13 1.1.4 La versione finale: il commento a caldo di Marilù…………….15 1.2 L’intervista……………………………………………………………….16 1.2.1 Sbobinatura……………………..……………………………………16 1.2.2 L’esprimersi vivo……………………………………………………...24 1.2.3 Il flusso di coscienza…………………………………………………25 1.3 (Tentativo di) biografia e filmografia……………………...............26 1.3.1 «Io non ho niente»: la scelta di Marilù........................................26 1.3.2 Autobiografia o biografia?.........................................................28 1.3.3 Biografia essenziale………………………………………………….29 1.3.4 Materiali fotografici e video: la Cinemathèque française ieri ed oggi………………………………………………………………...30 1.3.5 Filmografia ricavata da materiali vari e dall’intervista……….32 3 2. -

A Bela Intrigante Coisa, Você Pode Escolher Os Filmes Pelos Quais a (La Belle Noiseuse) I Você Se Influencia

1949 Aux quatre coins “O importante é aquilo que eu vejo a partir do 1950 Le quadrille que o ator “dá”, segundo um processo pessoal 1952 Le divertissement dele, que não me diz respeito. Quando Emanuelle [Béart] me propõe alguma coisa, ela não vem falar Le coup du berger 1956 comigo dizendo “E se eu fizesse isso...?” Ela faz. apresenta 1960 Paris nous appartient Em seguida eu vejo ela interpretar – não no visor 1966 A Religiosa (La religieuse) da câmera (eu sei muito bem o que ela filma, Cinéma de notre temps: Portrait conheço sua posição e sua óptica, que é quase de Michel Simon par Jean Renoir sempre a mesma) – e posso reagir em relação à ou Portrait de Jean Renoir par realidade, a uma matéria que existe. Essa Michel Simon ou La direction realidade, essa “matéria”, é Emanuelle atuando.” d’acteurs: dialogue (TV) “O fato de eu assistir a tantos filmes parece de fato Cinéma de notre temps: Jean assustar as pessoas. Muitos cineastas fingem que Renoir, le patron (TV) nunca vêem nada, e isso sempre pareceu muito 1969 L’amour fou estranho para mim. Todo mundo aceita o fato de 1971 Out 1 que escritores lêem livros, escritores vão a 1972 Out 1: Spectre (versão reduzida) exposições e inevitavelmente são influenciados pelo trabalho dos grandes artistas que vieram 1974 Céline et Julie vont en bateau antes deles, que os músicos ouçam música antiga Naissance et mont de Prométhée além das coisas novas... Então por que as pessoas 25 de Fevereiro de 2004 – Ano II – Edição nº 41 Essai sur l’agression acham estranho que cineastas – ou pessoas que 1976 Duelle (une quarantaine) querem tornar-se cineastas – vejam filmes? Noroît Quando você vê os filmes de certos diretores, 1981 Paris s’en va você pensa que a história do cinema começa para 1982 Le Pont du Nord eles em torno dos anos 80. -

Classic French Film Festival 2013

FIFTH ANNUAL CLASSIC FRENCH FILM FESTIVAL PRESENTED BY Co-presented by Cinema St. Louis and Webster University Film Series Webster University’s Winifred Moore Auditorium, 470 E. Lockwood Avenue June 13-16, 20-23, and 27-30, 2013 www.cinemastlouis.org Less a glass, more a display cabinet. Always Enjoy Responsibly. ©2013 Anheuser-Busch InBev S.A., Stella Artois® Beer, Imported by Import Brands Alliance, St. Louis, MO Brand: Stella Artois Chalice 2.0 Closing Date: 5/15/13 Trim: 7.75" x 10.25" Item #:PSA201310421 QC: CS Bleed: none Job/Order #: 251048 Publication: 2013 Cinema St. Louis Live: 7.25" x 9.75" FIFTH ANNUAL CLASSIC FRENCH FILM FESTIVAL PRESENTED BY Co-presented by Cinema St. Louis and Webster University Film Series The Earrings of Madame de... When: June 13-16, 20-23, and 27-30 Where: Winifred Moore Auditorium, Webster University’s Webster Hall, 470 E. Lockwood Ave. How much: $12 general admission; $10 for students, Cinema St. Louis members, and Alliance Française members; free for Webster U. students with valid and current photo ID; advance tickets for all shows are available through Brown Paper Tickets at www.brownpapertickets.com (search for Classic French) More info: www.cinemastlouis.org, 314-289-4150 The Fifth Annual Classic French Film Festival celebrates St. Four programs feature newly struck 35mm prints: the restora- Louis’ Gallic heritage and France’s cinematic legacy. The fea- tions of “A Man and a Woman” and “Max and the Junkmen,” tured films span the decades from the 1920s through the Jacques Rivette’s “Le Pont du Nord” (available in the U.S. -

A Mode of Production and Distribution

Chapter Three A Mode of Production and Distribution An Economic Concept: “The Small Budget Film,” Was it Myth or Reality? t has often been assumed that the New Wave provoked a sudden Ibreak in the production practices of French cinema, by favoring small budget films. In an industry characterized by an inflationary spiral of ever-increasing production costs, this phenomenon is sufficiently original to warrant investigation. Did most of the films considered to be part of this movement correspond to this notion of a small budget? We would first have to ask: what, in 1959, was a “small budget” movie? The average cost of a film increased from roughly $218,000 in 1955 to $300,000 in 1959. That year, at the moment of the emergence of the New Wave, 133 French films were produced; of these, 33 cost more than $400,000 and 74 cost more than $200,000. That leaves 26 films with a budget of less than $200,000, or “low budget productions;” however, that can hardly be used as an adequate criterion for movies to qualify as “New Wave.”1 Even so, this budgetary trait has often been employed to establish a genealogy for the movement. It involves, primarily, “marginal” films produced outside the dominant commercial system. Two Small Budget Films, “Outside the System” From the point of view of their mode of production, two titles are often imposed as reference points: Jean-Pierre Melville’s self-produced Silence of 49 A Mode of Production and Distribution the Sea, 1947, and Agnes Varda’s La Pointe courte (Short Point), made seven years later, in 1954.