Arbitration in Switzerland the Practitioner’S Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Watch on 2021 Uci Mountain Bike World Cup Team-Guide| 2 Event Information

WATCH ON 2021 UCI MOUNTAIN BIKE WORLD CUP TEAM-GUIDE| 2 EVENT INFORMATION ORGANIZING COMMITTEE CONTACTS LORDMAYORCITYOFALBSTADTCHIE F OF COURSES Klaus Konzelmann Olaf Holz, RSG Zollernalb mobile: +49 1788057962 MAYOR CITY OF ALBSTADT [email protected] Steve Mall COORDINATION OF THE EVENT VENUE OC LEADER Uli Bitzer, Jürgen Metzger, Skyder Marinus Merz , City of Albstadt mobile: +49 7434315333 mobile: +49 15232164687 [email protected] [email protected] TEAM ZONE MANAGER GENERAL MANAGER Adrian Wyler, Skyder Stephan Salscheider, Skyder mobile: +41792375373 mobile: +49 16094670294 [email protected] [email protected] TV & TIMING COORDINATOR RACE DIRECTOR Kim Salscheider, Skyder Ingolf Welsch, Skyder mobile: +49 15111658194 mobile: +49 1703181847 [email protected] UCI STAFF CHIEF OF MEDIA Armin Küstenbrück, EGO-Promotion AND REPRESENTATIVES mobile: +49 16093825739 [email protected] UCI OFF-ROAD MANAGER Simon Burney CORONA REGULATIONS TECHNICAL DELEGATE Hanna Pfaff , City of Albstadt mobile: +49 0152 29935795 Beat Wabel [email protected] PRESIDENT OF THE COMMISSAIRES’ PANEL Csilla Tam COMPETITION OFFICE / ACCREDITATION Esther Hofele, Katrin Metzger, Skyder RACE SECRETARY mobile: +49 7434-315333 Thierry Nuninger [email protected] MARKETING DELEGATE Jocelyn Rannou TV DELEGATE Susanne Lenz MEDICAL SERVICE A fully dedicated medical team will be availa- ble during all official practice and competition times. The medical team includes a doctor, pa- ramedics, and first responders. These resources will be strategically located on the courses as well as at the medical tent on the events side. International Emergency Call: 112 2021 UCI MOUNTAIN BIKE WORLD CUP TEAM-GUIDE| 3 GENERAL PLAN ENTRANCE G Mountain Rescue 7.-9. -

Ok-Fr-Belgian-Delegations-Summer

Délégations belges aux Jeux Olympiques d’été 34ème Olympiade d’été – Los Angeles, USA – 2028 33ème Olympiade d’été – Paris, France – 2024 32ème Olympiade d’été – Tokyo, Japon – 2020 31ème Olympiade d’été – Rio de Janeiro, Brésil – 2016 30ème Olympiade d’été – Londres, Angleterre – 2012 29ème Olympiade d’été – Pékin, Chine – 2008 28ème Olympiade d’été – Athènes, Grèce – 2004 27ème Olympiade d’été – Sydney, Australie – 2000 26ème Olympiade d’été – Atlanta, USA – 1996 25ème Olympiade d’été – Barcelone, Espagne – 1992 24ème Olympiade d’été – Séoul, Corée du Sud – 1988 23ème Olympiade d’été – Los Angeles, USA – 1984 22ème Olympiade d’été – Moscou, Russie – 1980 21ème Olympiade d’été – Montréal, Canada – 1976 20ème Olympiade d’été – Munich, Allemagne – 1972 19ème Olympiade d’été – Mexico, Mexique – 1968 18ème Olympiade d’été – Tokyo, Japon – 1964 17ème Olympiade d’été – Rome, Italie – 1960 16ème Olympiade d’été : Jeux équestres – Stockholm, Suède - 1956 16ème Olympiade d’été – Melbourne, Australie – 1956 15ème Olympiade d’été – Helsinki, Finlande – 1952 14ème Olympiade d’été – Londres, Angleterre – 1948 13ème Olympiade d’été – Londres, Angleterre – 1944 12ème Olympiade d’été – Tokyo, Japon – 1940 11ème Olympiade d’été – Berlin, Allemagne – 1936 10ème Olympiade d’été – Los Angeles, USA – 1932 9ème Olympiade d’été – Amsterdam, Pays-Bas – 1928 8ème Olympiade d’été – Paris, France – 1924 7ème Olympiade d’été – Anvers, Belgique – 1920 6ème Olympiade d’été – Berlin, Allemagne – 1916 5ème Olympiade d’été – Stockholm, Suède – 1912 4ème Olympiade d’été -

MILITARY AVIATION AUTHORITY Content

en MILITARY AVIATION AUTHORITY Content 2 — What we do _ Our mission _ Our vision _ Who we are 4 — Airworthiness 6 — Air Traffic Management (ATM) & Infrastructure 9 — Air Operation 11 — Defence Aviation Safety Management 13 — Swiss Air Force Aeromedical Institute 14 — Environment and Partnership 15 — Compliance and Quality Management 16 — Emblem Military Aviation Authority MAA Military airbase CH-1530 Payerne [email protected] www.armee.ch/maa Head of the Federal Department of Defence, Civil Protection and Sport DDPS, Federal Councillor Viola Amherd MAA, just three letters but a significant change for the Swiss military aviation. In today’s rapidly evolving world, where aviation is discover- ing a totally new range of operation with the emergence of drones and where access to airspace will soon be utmost critical, I am deeply per- suaded that the only way to achieve a maximized level of safety without prejudicing the operation in the interest of the state, is through magnifi- cation of the synergies between civil and military authorities. My prede- cessor has therefore ordered in 2017 the creation of the newborn Swiss MAA with the aim to maximize the coherence with FOCA, while high- lighting the specificities and needs of military aviation. The project team, under the lead of colonel GS Pierre de Goumoëns, was able to plan and initiate its deployment within a very short time period. I am very grate- ful to the whole team. Director of FOCA, Christian Hegner For decades, civilian aircraft and the Air Force have shared Swiss airspace. As a result, we have long had to work closely together to guarantee every- one the safe and efficient use of airspace. -

Historical Glacier Outlines from Digitized Topographic Maps of the Swiss Alps

Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 10, 805–814, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-10-805-2018 © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Historical glacier outlines from digitized topographic maps of the Swiss Alps Daphné Freudiger1,2, David Mennekes1, Jan Seibert2, and Markus Weiler1 1Chair of Hydrology, University of Freiburg, 79098, Freiburg, Germany 2Hydrology and Climate Unit, Department of Geography, University of Zurich, 8057, Zurich, Switzerland Correspondence: Daphné Freudiger ([email protected]) Received: 12 July 2017 – Discussion started: 4 August 2017 Revised: 26 February 2018 – Accepted: 23 March 2018 – Published: 20 April 2018 Abstract. Since the end of the Little Ice Age around 1850, the total glacier area of the central European Alps has considerably decreased. In order to understand the changes in glacier coverage at various scales and to model past and future streamflow accurately, long-term and large-scale datasets of glacier outlines are needed. To fill the gap between the morphologically reconstructed glacier outlines from the moraine extent corresponding to the time period around 1850 and the first complete dataset of glacier areas in the Swiss Alps from aerial photographs in 1973, glacier areas from 80 sheets of a historical topographic map (the Siegfried map) were manually digitized for the publication years 1878–1918 (further called first period, with most sheets being published around 1900) and 1917–1944 (further called second period, with most sheets being published around 1935). The accuracy of the digitized glacier areas was then assessed through a two-step validation process: the data were (1) visually and (2) quantitatively compared to glacier area datasets of the years 1850, 1973, 2003, and 2010, which were derived from different sources, at the large scale, basin scale, and locally. -

M Ountainbike Race Series

swisspowercup.ch mountaininternationalinbterinkatioena l mountainbikemroaunctainebik es raceraece rseriesseiries s2004 Durch das gute Konzept des Swisspower Cups und die konsequente KONTAKT Nachwuchsförderung sind die Schweizer Mountainbiker internationale Spitze, was die zahlreichen Podestplätze an internationalen Swisspower Cup, Postfach 33 Titelkämpfen beweisen. Die Leistungsdichte des Schweizer Bike- CH-8606 Nänikon Nachwuchses ist im internationalen Vergleich sehr hoch und so www.swisspowercup.ch blickt das Ausland neidisch auf unsere erfolgreiche Rennserie. [email protected] Doch vergangene Erfolge sind kein Grund, auf den Andi Seeli Loorbeeren auszuruhen. Der Nachwuchs will gefördert sein, [email protected] und zwar jedes Jahr aufs Neue. Das ausgesprochen gute Angebot für jüngere Teilnehmer und Teilnehmerinnen sowie René Walker die hohen Teilnehmerzahlen ermöglichen es, Talente landes- [email protected] weit frühzeitig auszuwählen und für den Mountainbikesport zu begeistern. Die Sieben- bis Zehnjährigen werden dabei in spieler- ischer Weise an den Mountainbikesport und die Wettkampfsituation herangeführt. Durch geeignete Streckenwahl wird auch für die älteren Kategorien auf die technischen Förderung grossen Wert gelegt. Da der Swisspower Cup 2004 in der Schweiz die einzige nationale Rennserie sein wird, blicken wir zuversichtlich in die Zukunft und sind überzeugt, mit dem Mountainbikesport und dem Konzept Swisspower Cup auf die richtige Karte zu setzen. Von unserem Konzept einer innovativen, qualitativ hochstehenden und weitsichtigen Rennserie sind auch Swisspower und ihre Partnerwerke (ewz, IWB, Energie Wasser Bern) nun schon im 4. Jahr als Hauptsponsor überzeugt. Da diese Unternehmungen für Innovation, Qualität und Weitsichtigkeit stehen, unterstützen sie auch dieses Jahr wieder unsere Innovationen für den Cup 2004. So können wir nun 12 statt der bisher 8 Rennen durchführen, bauen die Short Races aus, gestalten die Strecken zuschauer- und medienwirksamer und erweitern das Rahmen- programm mit weiteren Attraktionen. -

Peace Operations Training Institutions in Europe

Peace Operations Training Institutions in Europe M M M M M M M M M M M Peace Operations Training Institution M Click for more information. M M M M M M M M M M This overview is based on the members list of the M M M M M International Association of Peacekeeping Training M M M M Centres (IAPTC) and the members list of urope!s M M "ew Training Initiative for Civilian Crisis Management M M M M M (E"T$i). M M M M M M M M M M M M %or more information please visit& M M M M M M M www.iaptc.org M M M M M www.entriforccm.eu M M This list is not e'haustive. %or feedback and additions please contact& training()if*berlin.org www.zif-berlin.org Peace Operations Training #ilitar, Training Institution Police Training Institution Civilian Training Institution Institutions in Europe FBA Overview The %olke*+ernadotte*Academ, (%+A) is the -wedish agenc, for peace. securit, and development. %+A offers training course programmes for FBA civilian staff seconded through the %+A to international peace missions. The courses contain practical securit, trainings and theoretical parts. Location -and/verken. -weden GOV Contact Swedish Police PSO www.folkebernadotteacadem,.se Swedish Police PSO Overview The -wedish Police Peace -upport Operations unit (P-O) was created in 2000 to organise the participation of -wedish police officers in peace support operations from the #inistr, of 2efence. The pre*mission trainings are available also to police officers from other countries. Location SNDC -tockholm. -

Environmental DNA Simultaneously Informs Hydrological and Biodiversity Characterization of an Alpine Catchment

Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 25, 735–753, 2021 https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-25-735-2021 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Environmental DNA simultaneously informs hydrological and biodiversity characterization of an Alpine catchment Elvira Mächler1,2, Anham Salyani3, Jean-Claude Walser4, Annegret Larsen3,5, Bettina Schaefli3,6,7, Florian Altermatt1,2, and Natalie Ceperley3,6,7 1Eawag: Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, Department of Aquatic Ecology, Überlandstrasse 133, 8600 Dübendorf, Switzerland 2Institute of Evolutionary Biology and Environmental Studies, University of Zurich, Winterthurerstrasse 190, 8057 Zürich, Switzerland 3Faculty of Geosciences and Environment, Institute of Earth Surface Dynamics, University of Lausanne, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland 4Federal Institute of Technology (ETH), Zürich, Genetic Diversity Centre, CHN E 55 Universitätstrasse 16, 8092 Zürich, Switzerland 5Soil Geography and Landscape Group, Wageningen University, Droevendaalsesteeg 3, 6708 PB Wageningen, the Netherlands 6Geography Institute, University of Bern, 3012 Bern, Switzerland 7Oeschger Centre for Climate Change Research, University of Bern, Switzerland Correspondence: Elvira Mächler ([email protected]) and Natalie Ceperley ([email protected]) Received: 23 September 2020 – Discussion started: 7 October 2020 Revised: 24 December 2020 – Accepted: 29 December 2020 – Published: 18 February 2021 Abstract. Alpine streams are particularly valuable for down- conveyed by naturally occurring hydrologic tracers. Between stream water resources and of high ecological relevance; March and September 2017, we sampled water at multiple however, a detailed understanding of water storage and re- time points at 10 sites distributed over the 13.4 km2 Vallon lease in such heterogeneous environments is often still lack- de Nant catchment (Switzerland). -

Switzerland and Europe's Security Architecture

139 Heiko Borchert Switzerland and Europe’s Security Architecture: The Rocky Road from Isolation to Cooperation* Located in the heart of Europe, Switzerland has traditionally pursued a security policy based on the idea that the country is surrounded by enemies instead of by friends. Until the early 1990s, army planners and security experts adhered to Mearsheimer’s "back to the future" scenario and prepared for a European continent falling apart. Now, at the end of the century, we know that things look brighter. The magistrates in Bern realize that they are loosing ground, especially with respect to the former Communist countries now eagerly applying for membership in the European Union (EU) and in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). They risk being caught in what can be called the neutrality trap: Because of the favorable European security environment the political elite is not willing to discuss the use of neutrality in post-Cold War Europe. But it is exactly the lack of that discussion that makes it impossible for Switzerland to fully benefit from the favorable environment. The outcome is a dilemma: NATO membership is possible, but not desirable. EU membership is desirable, but not possible. In what follows I will look more closely at Switzerland’s relationship with Europe’s security architecture. I address first the most recent developments at the European level and argue that these changes narrow Switzerland’s foreign and security policy options. I then turn to Switzerland’s latest security policy report calling for "security through cooperation". Although the report sketches a good and sometimes brave vision, the proof – as always – lies in the eating. -

Evil Eye Geschichte

evil eye Geschichte 2000: evil eye Die Geburtsstunde der evil eye. Mit ihrer disruptiven Designsprache und ihrem aggressives Aussehen spricht sie vor allem junge Downhill-Mountainbiker und Freerider an. Entwickelt in Zusammenarbeit mit Pro-Ridern, die eine hohe Funktionalität unter extremen Bedingungen fordern, startet die evil eye zu ihrem Triumphzug als eine der bekanntesten und beliebtesten bike-spezifischen Brillen auf dem Markt. Die evil eye ist mit einer Vielzahl an Highlights ausgestattet, darunter dem Sweatbar (einem abnehmbaren System, welches hilft, Schweiß den Augen fernzuhalten), ultraleichtem, beständigem SPX™-Rahmenmaterial und 10-base Gläserkrümmung, um nur einige zu nennen. Zusätzlich baut adidas eyewear europaweit die ersten evil eye North Shore-Trails und entwirft technisch höchst anspruchsvolle evil eye-Lines in Bikeparks. „Es war uns wichtig, dass das Design des Rahmens dynamisch in Richtung der Bügel fließt. Das ließ sich hervorragend mit den Ventilationsöffnungen an der Seite und den weiten Bügeln beim Gelenk verbinden. Die integrierte Ventilation und der Sweatbar gegen das Beschlagen der Gläser wurden von Grund auf neu entwickelt. Ein weiterer wichtiger Faktor war die individuelle Anpassbarkeit, weshalb wir TRI.FIT™ und die Double-Snap Nose Bridge™ integrierten.“ Gerhard Fuchs | Designer Pro-Rider Top-Resultate: Olympische Spiele Straßenrennen | Sydney 2000 | 3.Platz - Andreas Klöden (GER) MTB XC Weltmeisterschaft | 2002 | 2.Platz - Filip Meirhaeghe (BEL) Weltcup MTB XC | 2002 | Gesamtsieger - Filip Meirhaeghe (BEL) -

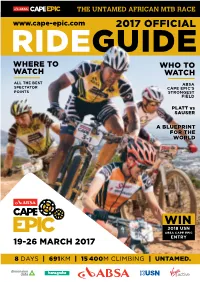

2017 Official Rideguide Where to Who to Watch Watch

THE UNTAMED AFRICAN MTB RACE www.cape-epic.com 2017 OFFICIAL RIDEGUIDE WHERE TO WHO TO WATCH WATCH ALL THE BEST ABSA SPECTATOR CAPE EPIC’S POINTS STRONGEST FIELD PLATT vs SAUSER A BLUEPRINT FOR THE WORLD WIN 2018 USN ABSA CAPE EPIC ENTRY 19-26 MARCH 2017 8 DAYS | 691KM | 15 400M CLIMBING | UNTAMED. A NEW MARK TO BE MEASURED BY The Absa Cape Epic is held in a place where anything can happen: Africa. Wild and open, sometimes inhospitable and other times staggeringly beautiful, this land both tests and surprises all who tackle its ungroomed trails. When the sounds of the cicadas are harsher than the heat they proclaim, when icy mornings lead to driving rain, you can be certain that both equipment and spirit will be pushed to the limit. In this place, where roads hardened year-round by the sun can turn to quicksand overnight, you and your partner will be challenged mentally, physically and emotionally. Yet still, Africa’s untamed majesty beckons. #UNTAMED BOOST ENERGY 3-Stage Glycomatrix carbohydrate BOOST OXYGEN drink for sustained energy during training and racing. Booster for optimal endurance REHYDRATES AND IMPROVES performance optimizer. RECOVERY AFTER TRAINING REPLACES ENERGY DURING INCREASES OXYGEN UPTAKE PHYSICAL ACTIVITY OPTIMIZES MUSCLE PERFORMANCE WHEN BEFORE TRAINING OR EVENT AND DURING WHEN TRAINING AND EVENTS LASTING UP TO TWO DURING TRAINING OR EVENT AS WELL HOURS PREPARE 1 TO 3 HOURS 3 HOURS & MORE Precision formula with carbs, Complete ultra-endurance drink amino acids and electrolytes for optimal performance and for optimal -

Wandel Der Schweizer Militärdoktrin Infolge Des Endes Des Kalten Krieges

PEACE RESEARCH INSTITUTE FRANKFURT Sabine Mannitz The Normative Construction of the Soldier in Switzerland: Constitutional Conditions and Public Political Discourse The Swiss Case PRIF- Research Paper No. I/9-2007 © PRIF & Sabine Mannitz 2007 Research Project „The Image of the Democratic Soldier: Tensions Between the Organisation of Armed Forces and the Principles of Democracy in European Comparison“ Funded by the Volkswagen Foundation 2006-2009 Contents Introduction 2 1. Historical Roots and Traditional Rationale of Conscription in Switzerland 3 2. The Swiss Militia System: How it Works 7 3. Post Cold-War Changes in the Constitutional Regulations and Task Allocations of the Swiss Armed Forces 11 4. The Swiss Format of Soldiering Contested 18 Final Remarks 25 References 27 Mannitz: German Case I/9-2007 2 Introduction In terms of its military system, Switzerland represents an odd case in present day comparison. At a time when more and more countries withdraw from maintaining conscription based armed forces, Switzerland continues to enforce compulsory military service for all male citizens. The maintenance of standing troops is prohibited in the constitution of the Swiss Federation. The military is organised in the fashion of a decentralised militia which is mobilised only for training. The militia systems shapes a mass reserve corps of a ‘nation in arms’ that is supplemented by a small number of professionals for stand-by, for the Swiss participation in out-of-area missions, and – foremost – for the instruction of the conscripts. Also in terms of its membership in international organisations and in defence communities in particular, Switzerland follows a distinct policy: The Swiss defence concept is tied to a foreign policy of neutrality, and the country is therefore keeping an isolationist profile in all of those international organisations that aim at collaboration in their foreign policies. -

Radial Growth Responses to Drought of Pinus Sylvestris and Quercus Pubescens in an Inner-Alpine Dry Valley

This document is the accepted manuscript version of the following article: Weber, P., Bugmann, H., & Rigling, A. (2007). Radial growth responses to drought of Pinus sylvestris and Quercus pubescens in an inner-Alpine dry valley. Journal of Vegetation Science, 18(6), 777-792. 1 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1654-1103.2007.tb02594.x 2 3 4 Radial growth responses to drought of Pinus sylvestris and 5 Quercus pubescens in an inner-Alpine dry valley 6 7 8 9 10 Weber, Pascale1*, Bugmann, Harald2 & Rigling, Andreas1 11 12 1Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research, WSL, Zürcherstrasse 111, CH-8903 13 Birmensdorf, Switzerland. Email [email protected] 14 2Forest Ecology, Department of Environmental Sciences, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH), ETH 15 Zentrum, CH-8092 Zürich, Switzerland. Email [email protected] 16 *Corresponding author; Fax +41 (0) 44 7392 215; Email [email protected] 17 2 Radial growth responses to drought 1 Abstract 2 Question: Lower-montane treeline ecotones such as the inner-Alpine dry valleys are regarded 3 as being sensitive to climate change. In Valais (Switzerland), one of the driest valleys of the 4 Alps, the composition of the widespread low-elevation pine forests is shifting towards a 5 mixed deciduous state. The evergreen sub-boreal Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) shows high 6 mortality rates, whereas the deciduous sub-Mediterranean pubescent oak (Quercus pubescens 7 Willd.) is spreading. Here, the two species may act as early indicators of climate change. In 8 the present study, we evaluate this hypothesis by focusing on their differences in drought 9 tolerance, which are hardly known, but are likely to be crucial in the current forest shift and 10 also for future forest development.