Afrocentricity: the Evolution of the Theo- Ry in the Context of American History*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kwame Nkrumah and the Pan- African Vision: Between Acceptance and Rebuttal

Austral: Brazilian Journal of Strategy & International Relations e-ISSN 2238-6912 | ISSN 2238-6262| v.5, n.9, Jan./Jun. 2016 | p.141-164 KWAME NKRUMAH AND THE PAN- AFRICAN VISION: BETWEEN ACCEPTANCE AND REBUTTAL Henry Kam Kah1 Introduction The Pan-African vision of a United of States of Africa was and is still being expressed (dis)similarly by Africans on the continent and those of Afri- can descent scattered all over the world. Its humble origins and spread is at- tributed to several people based on their experiences over time. Among some of the advocates were Henry Sylvester Williams, Marcus Garvey and George Padmore of the diaspora and Peter Abrahams, Jomo Kenyatta, Sekou Toure, Julius Nyerere and Kwame Nkrumah of South Africa, Kenya, Guinea, Tanza- nia and Ghana respectively. The different pan-African views on the African continent notwithstanding, Kwame Nkrumah is arguably in a class of his own and perhaps comparable only to Mwalimu Julius Nyerere. Pan-Africanism became the cornerstone of his struggle for the independence of Ghana, other African countries and the political unity of the continent. To transform this vision into reality, Nkrumah mobilised the Ghanaian masses through a pop- ular appeal. Apart from his eloquent speeches, he also engaged in persuasive writings. These writings have survived him and are as appealing today as they were in the past. Kwame Nkrumah ceased every opportunity to persuasively articulate for a Union Government for all of Africa. Due to his unswerving vision for a Union Government for Africa, the visionary Kwame Nkrumah created a microcosm of African Union through the Ghana-Guinea and then Ghana-Guinea-Mali Union. -

The Power to Say Who's Human

University at Albany, State University of New York Scholars Archive Africana Studies Honors College 5-2012 The Power to Say Who’s Human: Politics of Dehumanization in the Four-Hundred-Year War between the White Supremacist Caste System and Afrocentrism Sam Chernikoff Frunkin University at Albany, State University of New York Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/honorscollege_africana Part of the African Studies Commons Recommended Citation Frunkin, Sam Chernikoff, "The Power to Say Who’s Human: Politics of Dehumanization in the Four- Hundred-Year War between the White Supremacist Caste System and Afrocentrism" (2012). Africana Studies. 1. https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/honorscollege_africana/1 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at Scholars Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Africana Studies by an authorized administrator of Scholars Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Power to Say Who’s Human The Power to Say Who’s Human: Politics of Dehumanization in the Four-Hundred-Year War between the White Supremacist Caste System and Afrocentrism Sam Chernikoff Frumkin Africana Studies Department University at Albany Spring 2012 1 The Power to Say Who’s Human —Introduction — Race represents an intricate paradox in modern day America. No one can dispute the extraordinary progress that was made in the fifty years between the de jure segregation of Jim Crow, and President Barack Obama’s inauguration. However, it is equally absurd to refute the prominence of institutionalized racism in today’s society. America remains a nation of haves and have-nots and, unfortunately, race continues to be a reliable predictor of who belongs in each category. -

Kwame Nkrumah, His Afro-American Network and the Pursuit of an African Personality

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 3-22-2019 Kwame Nkrumah, His Afro-American Network and the Pursuit of an African Personality Emmanuella Amoh Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the African History Commons Recommended Citation Amoh, Emmanuella, "Kwame Nkrumah, His Afro-American Network and the Pursuit of an African Personality" (2019). Theses and Dissertations. 1067. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/1067 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KWAME NKRUMAH, HIS AFRO-AMERICAN NETWORK AND THE PURSUIT OF AN AFRICAN PERSONALITY EMMANUELLA AMOH 105 Pages This thesis explores the pursuit of a new African personality in post-colonial Ghana by President Nkrumah and his African American network. I argue that Nkrumah’s engagement with African Americans in the pursuit of an African Personality transformed diaspora relations with Africa. It also seeks to explore Black women in this transnational history. Women are not perceived to be as mobile as men in transnationalism thereby underscoring their inputs in the construction of certain historical events. But through examining the lived experiences of Shirley Graham Du Bois and to an extent Maya Angelou and Pauli Murray in Ghana, the African American woman’s role in the building of Nkrumah’s Ghana will be explored in this thesis. -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

John Henrik Clarke: a Great and Mighty Walk

AFRICAN DIASPORA ANCESTRAL COMMEMORATION INSTITUTE 25th Annual Commemoration for the Millions of African Ancestors Who Perished in the Middle Passage – the Maafa – and Those Who Survived Saturday – 10 June and Sunday – 11 June 2017 The Ancestors Speak: A Message of Renewal, Redemption and Rededication Saturday – 10 June 2017 • 9:30am – 1pm River Walk and Spiritual Healing Ceremony – Anacostia Park Assemble at 9:30am Union Temple Baptist Church • 1225 W Street SE • Washington, DC Libations • Prayers • Ceremonial Drumming • Procession to Anacostia River – 10:30am – 1pm Babalawo Fakunle Oyesanya – Officiating Reception – Lite Refreshments • Anacostia Arts Center – 1231 Good Hope Road SE ATTENDEES ARE ASKED TO WEAR WHITE CLOTHING Simultaneous Commemoration Activities at ADACI Sites in Detroit, Senegal, Nigeria, Brazil and Cuba Honorees ADACI Walking in the Footsteps of the Ancestors Award to Michael Brown ADACI annoD Sister of Strength Awards to Nana Malaya Rucker-Oparabea • Afua MonaCheri Pollard • Lydia Curtis • Akilah Karima Cultural Presentations KanKouran Children’s Company – Ateya Ball-Lacy – Dance Instructor • Celillianne Greene – Poet African Diaspora Ancestral Commemoration Institute Info: 202.558.2187 • 443.570.5667 (Baltimore) • www.adaciancestors.org. • [email protected] For worldwide middle passage remembrance activities see www.RememberTheAncestors.com International Coalition to Commemorate the African Ancestors of the Middle Passage (ICCAAMP) The Smithsonian National Museum of African Art in cooperation with the African Diaspora Ancestral Commemoration Institute (ADACI) presents the documentary John Henrik Clarke: A Great and Mighty Walk OHN HENRIK CLARKE Sunday • 11June 2017 JA GREAT AND MIGHTY WALK 12:30pm – 4:30pm Smithsonian National Museum of African Art 950 Independence Avenue SW Washington, DC 20560 Lecture Hall – 2nd Level This 1996 documentary chronicles the life and times of the noted African-American historian, scholar and Pan-African activist Dr. -

A PSYCHOMETRIC EXAMINATION of the AFRICENTRIC SCALE Challenges in Measuring Afrocentric Values

10.1177/0021934704266596JOURNALCokley, Williams OF BLACK / A PSYCHOMETRIC STUDIES / JULY EXAMINATION 2005 ARTICLE A PSYCHOMETRIC EXAMINATION OF THE AFRICENTRIC SCALE Challenges in Measuring Afrocentric Values KEVIN COKLEY University of Missouri at Columbia WENDI WILLIAMS Georgia State University The articulation of an African-centered paradigm has increasingly become an important component of the social science research published on people of African descent. Although several instruments exist that operationalize different aspects of an Afrocentric philosophical paradigm, only one instru- ment, the Africentric Scale, explicitly operationalizes Afrocentric values using what is arguably the most commercial and accessible understanding of Afrocentricity, the seven principles of the Nguzu Saba. This study exam- ined the psychometric properties of the Africentric Scale with a sample of 167 African American students. Results of a factor analysis revealed that the Africentric Scale is best conceptualized as measuring a general di- mension of Afrocentrism rather than seven separate principles. The find- ings suggest that with continued research, the Africentric Scale will be an increasingly viable option among the handful of measures designed to assess some aspect of Afrocentric values, behavioral norms, and an African worldview. Keywords: African-centered psychology; Afrocentric cultural values For at least three decades, Black psychologists have devoted their lives to undo the racist and maleficent theory and practice of main- stream or European-centered psychological practice. Nobles (1986) succinctly surveys the work and conclusions of prominent European-centered psychologists and concludes that the European- centered approach to inquiry as well as the assumptions made con- JOURNAL OF BLACK STUDIES, Vol. 35 No. 6, July 2005 827-843 DOI: 10.1177/0021934704266596 © 2005 Sage Publications 827 828 JOURNAL OF BLACK STUDIES / JULY 2005 cerning people of African descent are inappropriate in understand- ing people of African descent. -

Program for the 23Rd Conference

rd 23 Annual Cheikh Anta Diop International Conference “Fundamentals and Innovations in Afrocentric Research: Mapping Core and Continuing Knowledge of African Civilizations” October 7-8, 2011 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 7 Registration 7:30am-5:00pm Drum Call 8:15am-8:30am Opening Ceremony and Presentation of Program 8:30am-9:00am Panel 1 - Education Primers and Educational Formats for Proficiency in African Culture 9:00am-10:10am 1) Dr. Daphne Chandler “Martin Luther King, Jr. Ain’t All We Got”: Achieving and Maintaining Cultural Equilibrium in 21st Century Western-Centered Schools 2) Dr. Nosakare Griffin-El Trans-Defining Educational Philosophy for People of Africana Descent: Towards the Transconceptual Ideal of Education 3) Dr. George Dei African Indigenous Proverbs and the Instructional and Pedagogic Relevance for Youth Education Locating Contemporary Media and Social Portrayals of African Agency 10:15am-11:25am 1) Dr. Ibram Rogers A Social Movement of Social Movements: Conceptualizing a New Historical Framework for the Black Power Movement 2) Dr. Marquita Pellerin Challenging Media Generated Portrayal of African Womanhood: Utilizing an Afrocentric Agency Driven Approach to Define Humanity 3) Dr. Martell Teasley Barrack Obama and the Politics of Race: The Myth of Post-racism in America Keynote Address Where Myth and Theater Meet: Re-Imaging the Tragedy of Isis and Osiris 11:30am-12:15pm Dr. Kimmika Williams‐Witherspoon Lunch 12:15pm-1:45pm Philosophy and Practice of Resurgence and Renaissance 1:45pm-3:00pm 1)Abena Walker Ancient African Imperatives to Facilitate a Conscious Disconnect from the Fanatical Tyranny of Imperialism: The Development of Wholesome African Objective for Today’s Africans 2) Kwasi Densu Omenala (Actions in Accordance With the Earth): Towards the Development of an African Centered Environmental Philosophy and Its Implications for Africana Studies 3) Dr. -

A Critical Analysis of African-Centered Psychology: from Ism to Praxis

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 35 Issue 1 Article 9 1-1-2016 A Critical Analysis of African-Centered Psychology: From Ism to Praxis A. Ebede-Ndi California Institute of Integral Studies Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychology Commons, Religion Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Ebede-Ndi, A. (2016). A critical analysis of African-centered psychology: From ism to praxis. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 35 (1). http://dx.doi.org/10.24972/ijts.2016.35.1.65 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Special Topic Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Critical Analysis of African-Centered Psychology: From Ism to Praxis A. Ebede-Ndi California Institute of Integral Studies San Francisco, CA, USA The purpose of this article is to critically evaluate what is perceived as shortcomings in the scholarly field of African-centered psychology and mode of transcendence, specifically in terms of the existence of an African identity. A great number of scholars advocate a total embrace of a universal African identity that unites Africans in the diaspora and those on the continent and that can be used as a remedy to a Eurocentric domination of psychology at the detriment of Black communities’ specific needs. -

The Case Against Afrocentrism. by Tunde Adeleke

50 The Case Against Afrocentrism. By Tunde Adeleke. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2009. 224 pp. Since the loosening of Europe’s visible political and social clutch on the continent of Africa, conversations underlining common experiences and links between Black Africans and Blacks throughout the Diaspora have amplified and found merit in the Black intellectual community. Afrocentrist, such as Molefi Asante, Marimba Ani, and Maulana Karenga, have used Africa as a source of all Black identity, formulating a monolithic, essentialist worldview that underscores existing fundamentally shared values and suggests a unification of all Blacks under one shared ideology for racial uplift and advancement. In the past decade, however, counterarguments for such a construction have found their way into current discourses, challenging the idea of a worldwide, mutual Black experience that is foundational to Afrocentric thought. In The Case Against Afrocentrism, Tunde Adeleke engages in a deconstruction and reconceptualization of the various significant paradigms that have shaped the Afrocentric essentialist perspective. Adeleke’s text has obvious emphasis on the difficulty of utilizing Africa in the construction of Black American identity. A clear supporter of the more “realistic” Du Boisian concept of double-consciousness in the Black American experience, Adeleke challenges Afrocentrists’, mainly Molefi Asante’s, rejection of the existence of American identity within a Black body. He argues against the “flawed” perception that Black Americans remain essentially African despite centuries of separation in slavery. According to Adeleke, to suggest that Blacks retain distinct Africanisms undermines the brutality and calculating essence of the slave system that served as a process of “unmasking and remaking of a people’s consciousness of self” (32). -

Movement of the People: the Relationship Between Black Consciousness Movements

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 4-7-2008 Movement Of The eople:P The Relationship Between Black Consciousness Movements, Race, and Class in the Caribbean Deborah G. Weeks University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Weeks, Deborah G., "Movement Of The eP ople: The Relationship Between Black Consciousness Movements, Race, and Class in the Caribbean" (2008). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/560 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Movement Of The People: The Relationship Between Black Consciousness Movements, Race, and Class in the Caribbean by Deborah G. Weeks A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts Department of Africana Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-Major Professor: Deborah Plant, Ph.D. Co-Major Professor: Eric D. Duke, Ph.D. Navita Cummings James, Ph.D. Date of Approval: April 7, 2008 Keywords: black power, colonization, independence, pride, nationalism, west indies © Copyright 2008 , Deborah G. Weeks Dedication I dedicate this thesis to the memory of Dr. Trevor Purcell, without whose motivation and encouragement, this work may never have been completed. I will always remember his calm reassurance, expressed confidence in me, and, of course, his soothing, melodic voice. -

Ali a Mazrui on the Invention of Africa and Postcolonial Predicaments1

‘My life is One Long Debate’: Ali A Mazrui on the Invention of Africa and Postcolonial Predicaments1 Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni2 Archie Mafeje Research Institute University of South Africa Introduction It is a great honour to have been invited by the Vice-Chancellor and Rector Professor Jonathan Jansen and the Centre for African Studies at the University of the Free State (UFS) to deliver this lecture in memory of Professor Ali A. Mazrui. I have chosen to speak on Ali A. Mazrui on the Invention of Africa and Postcolonial Predicaments because it is a theme closely connected to Mazrui’s academic and intellectual work and constitute an important part of my own research on power, knowledge and identity in Africa. Remembering Ali A Mazrui It is said that when the journalist and reporter for the Christian Science Monitor Arthur Unger challenged and questioned Mazrui on some of the issues raised in his televised series entitled The Africans: A Triple Heritage (1986), he smiled and responded this way: ‘Good, [...]. Many people disagree with me. My life is one long debate’ (Family Obituary of Ali Mazrui 2014). The logical question is how do we remember Professor Ali A Mazrui who died on Sunday 12 October 2014 and who understood his life to be ‘one long debate’? More importantly how do we reflect fairly on Mazrui’s academic and intellectual life without falling into the traps of what the South Sudanese scholar Dustan M. Wai (1984) coined as Mazruiphilia (hagiographical pro-Mazruism) and Mazruiphobia (aggressive anti-Mazruism)? How do we pay tribute -

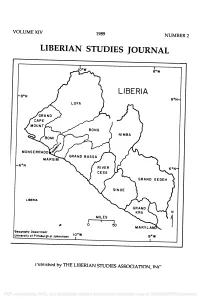

Liberian Studies Journal

VOLUME XIV 1989 NUMBER 2 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL r 8 °W LIBERIA -8 °N 8 °N- MONSERRADO MARGIBI MARYLAND Geography Department 10 °W University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown 8oW 1 Published by THE LIBERIAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION, INC. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor Cover map: compiled by William Kory, cartography work by Jodie Molnar; Geography Department, University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor VOLUME XIV 1989 NUMBER 2 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL Editor D. Elwood Dunn The University of the South Associate Editor Similih M. Cordor Kennesaw College Book Review Editor Dalvan M. Coger Memphis State University EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Bertha B. Azango Lawrence B. Breitborde University of Liberia Beloit College Christopher Clapham Warren L. d'Azevedo Lancaster University University of Nevada Reno Henrique F. Tokpa Thomas E. Hayden Cuttington University College Africa Faith and Justice Network Svend E. Holsoe J. Gus Liebenow University of Delaware Indiana University Corann Okorodudu Glassboro State College Edited at the Department of Political Science, The University of the South PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor CONTENTS THE LIBERIAN ECONOMY ON APRIL 1980: SOME REFLECTIONS 1 by Ellen Johnson Sirleaf COGNITIVE ASPECTS OF AGRICULTURE AMONG THE KPELLE: KPELLE FARMING THROUGH KPELLE EYES 23 by John Gay "PACIFICATION" UNDER PRESSURE: A POLITICAL ECONOMY OF LIBERIAN INTERVENTION IN NIMBA 1912 -1918 ............ 44 by Martin Ford BLACK, CHRISTIAN REPUBLICANS: DELEGATES TO THE 1847 LIBERIAN CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION ........................ 64 by Carl Patrick Burrowes TRIBE AND CHIEFDOM ON THE WINDWARD COAST 90 by Warren L.