Representatives of Roman Rule: Roman Governors in Luke-Acts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the D

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Marion Woodrow Kruse, III Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Anthony Kaldellis, Advisor; Benjamin Acosta-Hughes; Nathan Rosenstein Copyright by Marion Woodrow Kruse, III 2015 ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the use of Roman historical memory from the late fifth century through the middle of the sixth century AD. The collapse of Roman government in the western Roman empire in the late fifth century inspired a crisis of identity and political messaging in the eastern Roman empire of the same period. I argue that the Romans of the eastern empire, in particular those who lived in Constantinople and worked in or around the imperial administration, responded to the challenge posed by the loss of Rome by rewriting the history of the Roman empire. The new historical narratives that arose during this period were initially concerned with Roman identity and fixated on urban space (in particular the cities of Rome and Constantinople) and Roman mythistory. By the sixth century, however, the debate over Roman history had begun to infuse all levels of Roman political discourse and became a major component of the emperor Justinian’s imperial messaging and propaganda, especially in his Novels. The imperial history proposed by the Novels was aggressivley challenged by other writers of the period, creating a clear historical and political conflict over the role and import of Roman history as a model or justification for Roman politics in the sixth century. -

Language Contact and Identity in Roman Britain

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 5-16-2016 12:00 AM Language Contact and Identity in Roman Britain Robert Jackson Woodcock The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Professor Alexander Meyer The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Classics A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Robert Jackson Woodcock 2016 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Indo- European Linguistics and Philology Commons Recommended Citation Woodcock, Robert Jackson, "Language Contact and Identity in Roman Britain" (2016). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3775. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3775 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Language is one of the most significant aspects of cultural identity. This thesis examines the evidence of languages in contact in Roman Britain in order to determine the role that language played in defining the identities of the inhabitants of this Roman province. All forms of documentary evidence from monumental stone epigraphy to ownership marks scratched onto pottery are analyzed for indications of bilingualism and language contact in Roman Britain. The language and subject matter of the Vindolanda writing tablets from a Roman army fort on the northern frontier are analyzed for indications of bilingual interactions between Roman soldiers and their native surroundings, as well as Celtic interference on the Latin that was written and spoken by the Roman army. -

The Tuesday Afternoon Bible Study - Acts 23

The Tuesday Afternoon Bible Study - Acts 23 Acts 21-28 encompass several years, covering a long period of time in which Paul is always in captivity. Chapters 21-23 tell the first episode in this period, where Paul’s life is threatened three times. Paul has returned to Jerusalem, where so long ago (back in ch 8) he launched his persecution again Christians. Paul’s presence in the temple causes an angry mob to seize him, bringing Roman soldiers to keep the peace, and thus saving him. When the soldiers learn that Paul is a Roman citizen, this allows him a favored status. Allowed to speak to the Jews, in ch 22 Paul offers his defense. After his speech, the Roman tribune in charge wants to understand more about these charges leveled against Paul by the Jews. He orders Paul to speak before Jerusalem’s high-ranking Jewish leaders (sometimes referred to by the Greek word for council, Sanhedrin.) Ch 23 tells of this next encounter. (Hint: it won’t end well.) Let’s read ch 23 in three sections, answering questions after reading each section. Acts 23: 1-11 Read all of Paul’s speech before this gathered body of Jewish leaders. 1. Speaking truth to power is dangerous and can result in injury. Paul starts with a statement about his long-standing faithfulness to the God of Israel. This results in an order by the high priest, Ananias, for Paul to be struck on the mouth. This is the third person named Ananias we encounter in Acts - all 3 are different persons, and the first time we encounter this one. -

Paul's Trial Before Felix

PAUL’S TRIAL BEFORE FELIX Acts 24:1-27 STRUCTURE Key-persons: Paul, Governor Felix, and Jewish leaders from Jerusalem Key-location: Caesarea Key-repetitions: • Accusations against Paul: was a troublemaker (Ac 24:5); stirred up riots among the Jews everywhere (Ac 24:5); was a ringleader of the Nazarene sect (Ac 24:5); tried to desecrate the temple (Ac 24:6). • Paul confessed: went to Jerusalem to worship (Ac 24:11); worshiped God as a follower of the Way (Ac 24:14); believed the Mosaic Law and the prophets (Ac 24:14); believed there would be a resurrection (Ac 24:15); strived to do right (Ac 24:16). • Paul denied: arguing at the temple Ac 24:12); stirring up conflict in the synagogues or the city Ac 24:12); being involved in any disturbance (Ac 24:18). • Injustice against Paul: falsely accused by the Jewish leaders (Ac 24:4-9); Governor Felix left Paul in prison to please the Jews (Ac 24:27). Key-attitudes: • Jewish leaders’ hatred for Paul. • Paul’s confidence in God. • Governor Felix’s inconsistency. Initial-situation: Paul finished his third missionary journey by traveling to Jerusalem. Jews from Asia falsely accused Paul of bringing non-Jews into the temple courtyard. A mob seized Paul and beat him. The Roman commander arrested Paul while the crowd kept shouting, “Kill him!” The day after Paul was arrested, the Roman commander ordered the Sanhedrin Jewish Council to assemble and explain why Paul was being accused. The Sanhedrin Council meeting became violent. The commander ordered his soldiers to take Paul away by force and bring him into the barracks. -

Paul & Philippians Intermediate Kids Camp Workbook 2016

The Journeys of Paul and his letter to the Philippians “I press toward the mark for the prize of the high calling of God in Christ Jesus” Christadelphian Kids Camp, California 2016 Intermediate Workbook name______________________ parent signature______________________ This section reserved for your counselors who will be reviewing and marking your work. Overall Comments: ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ☐Bible Marking Completed ☐Project Completed The following questions were not completed or need more work. Please finish them, and return to your counselor. " Let your teacher or counselor know if you need help. Question # Comments Done !a Before You Begin… Plan: Use this chart to set your goals and track your progress. You should be able to complete the workbook with • time to spare by working on it just a bit each day. Dates Goal Actual Don’t wait till the last minute to start. You may not get it done in time, and you definitely won’t get as much out -

Peter Saccio

Great Figures of the New Testament Parts I & II Amy-Jill Levine, Ph.D. PUBLISHED BY: THE TEACHING COMPANY 4840 Westfields Boulevard, Suite 500 Chantilly, Virginia 20151-2299 1-800-TEACH-12 Fax—703-378-3819 www.teach12.com Copyright © The Teaching Company, 2002 Printed in the United States of America This book is in copyright. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of The Teaching Company. Amy-Jill Levine, Ph.D. E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Professor of New Testament Studies Vanderbilt University Divinity School/ Vanderbilt University Graduate Department of Religion Amy-Jill Levine earned her B.A. with high honors in English and Religion at Smith College, where she graduated magna cum laude and was a member of Phi Beta Kappa. Her M.A. and Ph.D. in Religion are from Duke University, where she was a Gurney Harris Kearns Fellow and W. D. Davies Instructor in Biblical Studies. Before moving to Vanderbilt, she was Sara Lawrence Lightfoot Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Religion at Swarthmore College. Professor Levine’s numerous publications address Second-Temple Judaism, Christian origins, Jewish-Christian relations, and biblical women. She is currently editing the twelve-volume Feminist Companions to the New Testament and Early Christian Literature for Continuum, completing a manuscript on Hellenistic Jewish narratives for Harvard University Press, and preparing a commentary on the Book of Esther for Walter de Gruyter (Berlin). -

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome William E. Dunstan ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC. Lanham • Boulder • New York • Toronto • Plymouth, UK ................. 17856$ $$FM 09-09-10 09:17:21 PS PAGE iii Published by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 http://www.rowmanlittlefield.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright ᭧ 2011 by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. All maps by Bill Nelson. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. The cover image shows a marble bust of the nymph Clytie; for more information, see figure 22.17 on p. 370. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dunstan, William E. Ancient Rome / William E. Dunstan. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7425-6832-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-7425-6833-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-7425-6834-1 (electronic) 1. Rome—Civilization. 2. Rome—History—Empire, 30 B.C.–476 A.D. 3. Rome—Politics and government—30 B.C.–476 A.D. I. Title. DG77.D86 2010 937Ј.06—dc22 2010016225 ⅜ϱ ீThe paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/ NISO Z39.48–1992. Printed in the United States of America ................ -

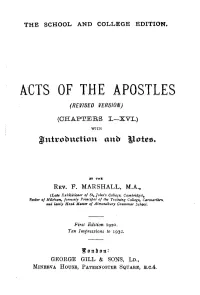

A:Cts of the Apostles (Revised Version)

THE SCHOOL AND COLLEGE EDITION. A:CTS OF THE APOSTLES (REVISED VERSION) (CHAPTERS I.-XVI.) WITH BY THK REV. F. MARSHALL, M.A., (Lau Ezhibition,r of St, John's College, Camb,idge)• Recto, of Mileham, formerly Principal of the Training College, Ca11narthffl. and la1ely Head- Master of Almondbury Grammar School, First Edition 1920. Ten Impressions to 1932. Jonb.on: GEORGE GILL & SONS, Ln., MINERVA HOUSE, PATERNOSTER SQUARE, E.C.4. MAP TO ILLUSTRATE THE ACTS OPTBE APOSTLES . <t. ~ -li .i- C-4 l y .A. lO 15 20 PREFACE. 'i ms ~amon of the first Sixteen Chapters of the Acts of the Apostles is intended for the use of Students preparing for the Local Examina tions of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge and similar examinations. The Syndicates of the Oxford and Cambridge Universities often select these chapters as the subject for examination in a particular year. The Editor has accordingly drawn up the present Edition for the use of Candidates preparing for such Examinations. The Edition is an abridgement of the Editor's Acts of /ht Apostles, published by Messrs. Gill and Sons. The Introduction treats fully of the several subjects with which the Student should be acquainted. These are set forth in the Table of Contents. The Biographical and Geographical Notes, with the complete series of Maps, will be found to give the Student all necessary information, thns dispensing with the need for Atlas, Biblical Lictionary, and other aids. The text used in this volume is that of the Revised Version and is printed by permission of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, but all editorial responsibility rests with the editor of the present volume. -

Fresh Light on the Governors of Judea

Endnotes for Fresh Light on the Governors of Judea Summer 2017 Bible and Spade Notes 1 Emil Schürer, The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ (175 BC– AD 135) , eds. G. Vermes, F. Miller, and M. Black. 4 Vols. (Edinburgh, UK: T&T Clark, 1979), p. 240. 2 Shimon Applebaum, Judaea in Hellenistic and Roman Times: Historical and Archaeological Essays , eds. J. Neusner (Leiden: Brill Academic, 1989), p.123. 3 Flavius Josephus, Jewish Antiquities , Volume VI, Books 14–15. Trans. R. Marcus and A. Wikgren. Vol. 10. Loeb Classical Library 489 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1943), 14.5.4. 4 For a list of Latin terms used in ancient sources for Governor, see Appendix G in Simon Corcoran’s The Empire of the Tetrarchs: Imperial Pronouncements and Government, AD 284–324 (Oxford, UK: Clarendon, 2000), pp. 337–39. 5 Fred K. Drogula, The Office of the Provincial Governor under the Roman Republic and Empire [to AD 235]: Conception and Tradition . Unpublished PhD Dissertation, University of Virginia, 2005; Walter Eder, “Governor,” BrillPauly , http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1574–9347_bnp_e1121630 , 2006 (accessed December 2016); Daniëlle Slootjes, The Governor and His Subjects in the Later Roman Empire (Leiden: Brill, 2006). 6 Ruth B. Edwards, “Rome,” Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels , eds. J.B. Green, S. McKnight, and I.H. Marshall (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 1992), p. 712. 7 Egypt was directly ruled by the Emperor, so the governor of Egypt held a unique role called Praefectus Aegypti . Ulpian, The Digest of Justinian . Trans. and ed. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 74-10,982

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. White the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Que Se Sabe De… La Biblia Desde La Arqueología

La Biblia desde la arqueología Qué se sabe de... Colección dirigida y coordinada por: CARLOS J. GIL ARBIOL La Biblia desde la arqueología Joaquín González Echegaray Editorial Verbo Divino Avenida de Pamplona, 41 31200 Estella (Navarra), España Teléfono: 948 55 65 05 Fax: 948 55 45 06 www.verbodivino.es [email protected] Diseño de colección y cubierta: Francesc Sala Fotografía: Ruinas de la ciudad de Gadara en la Decápolis (hoy Umm Qais, Jordania). © Joaquín González Echegaray © Editorial Verbo Divino, 2010 Fotocomposición: NovaText, Mutilva Baja (Navarra) Impresión: I.G. Castuera, S.A. (Navarra) Impreso en España - Printed in Spain Depósito legal: NA 359-2010 ISBN: 978-84-9945-011-7 Cualquier forma de reproducción, distribución, comunicación pública o transformación de esta obra solo puede ser realizada con la autorización de sus titulares, salvo excepción prevista por la ley. Diríjase a CEDRO (Centro Es- pañol de Derechos Reprográficos: www.cedro.org) si necesita fotocopiar o escanear algún fragmento de esta obra. Para comprender este libro INTRODUCCIÓN urante siglos, nuestros conocimientos sobre la historia anti- gua del Próximo Oriente se fundaban en los datos conteni- Ddos en la Biblia y en algunas fuentes principalmente griegas, como los Nueve libros de la Historia de Heródoto, los fragmentos con- servados de la Aegyptiaca de Manetón, la Ciropedia y la Anábasis de Je- nofonte, así como otras referencias menores de ciertos autores grie- gos y latinos. Nadie discutía su veracidad, ni tampoco existía mayor interés en un conocimiento más profundo del tema. Hay que esperar al siglo XVIII, para que los viajes de europeos a esos países de oriente, la contemplación de las monumentales ruinas aún visibles y el des- cubrimiento fortuito de inscripciones y objetos despertara interés en nuestro mundo occidental. -

Numenius and the Hellenistic Sources of the Central Christian Doctrine

! Numenius and the Hellenistic Sources ! of the Central Christian Doctrine Marian Hillar Center for Philosophy and Socinian Studies Houston, TX 77004 Paper published in A Journal from the Radical Reformation. A testimony to Biblical Unitarianism. Vol. 14, No.! 1, Spring 2007, pp. 3-31. Quis obsecro, nisi penitus amens logomachias has sine risu toleraret? Nec in Thalmud, nec in Alchoran, sunt tam horrendae blasfemiae. Haec nos hactenus audire ita sumus alsuefacti, ut nihil miremur. Futurae vero generationes stupenda haec iudicabunt. Stupenda sunt vere, plusquam ea daemonum inventa, quae Valentinianis tribuit Irenaeus. I implore you, who in his sane mind could tolerate such logomachias without bursting into laughter? Not in the Talmud, nor in the Qu’ran can one find such horrendous blasphemies. But we are accustomed to hear them to the point that nothing astonishes us. Future generations will judge them obscure. Indeed, they are obscure, much more than the diabolic inventions which Irenaeus attributed to the Valentinians. ! Michael Servetus Christianismi Restitutio, De Trinitate, lib. I. p. 46. Si locum mihi aliquem ostendas, quo verbum illud filius olim vocetur, fatebor me victum. Christianismi Restitutio, If you show me a single passage in which the Son was called the Word, I will give up. Michael Servetus, Christianismi Restitutio, De Trinitate, lib. III p. 108. ! Abstract This paper attempts to explain the sources of the central Christian doctrine about the nature of deity. We can trace a continuous line of thought from the Greek philosophy to the development of the doctrine of the Trinity. The first Christian doctrine was developed by Justin Martyr (114-165 C.E.).