Doctoral Thesis Effectiveness of Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitors in Patients

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

18-0969: R.S. and DEPARTMENT of the ARMY, WALTER

United States Department of Labor Employees’ Compensation Appeals Board __________________________________________ ) R.S., Appellant ) ) and ) Docket No. 18-0969 ) Issued: March 27, 2019 DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY, WALTER ) REED NATIONAL MILITARY MEDICAL ) CENTER, Bethesda, MD, Employer ) _________________________________________ ) Appearances: Case Submitted on the Record Appellant, pro se Office of Solicitor, for the Director DECISION AND ORDER Before: CHRISTOPHER J. GODFREY, Chief Judge PATRICIA H. FITZGERALD, Deputy Chief Judge VALERIE D. EVANS-HARRELL, Alternate Judge JURISDICTION On April 10, 2018 appellant filed a timely appeal from a December 22, 2017 merit decision of the Office of Workers’ Compensation Programs (OWCP). Pursuant to the Federal Employees’ Compensation Act1 (FECA) and 20 C.F.R. §§ 501.2(c) and 501.3, the Board has jurisdiction over the merits of this case.2 ISSUE The issue is whether appellant has met her burden of proof to establish lumbar and/or right shoulder conditions causally related to an April 7, 2016 employment incident. 1 5 U.S.C. § 8101 et seq. 2 The Board notes that following the December 22, 2017 decision, OWCP received additional evidence. However, the Board’s Rules of Procedure provides: “The Board’s review of a case is limited to the evidence in the case record that was before OWCP at the time of its final decision. Evidence not before OWCP will not be considered by the Board for the first time on appeal.” 20 C.F.R. § 501.2(c)(1). Thus, the Board is precluded from reviewing this additional evidence for the first time on appeal. Id. FACTUAL HISTORY On April 15, 2016 appellant, then a 64-year-old radiology technology supervisor, filed a traumatic injury claim (Form CA-1) alleging that on April 7, 2016 she injured her lower back and right shoulder while in the performance of duty. -

Tuberculous Spondylitis, Pyogenic Spondylitis, X-Ray and Tomographic Features

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences 2021, 11(5): 398-401 DOI: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20211105.08 X-Ray and Tomographic Manifestations of Tuberculous Spondylitis Babоev Abduvakhob Sakhibnazarovich Bone and Joint Tuberculosis Department of Rebuplican Specialized Scientific Practical Medical Center of Phtiziology and Pulmonology, Tashkent, Uzbekistan Abstract X-ray and tomographic data of seventy-eight patients with spine disorders (31 patients with tuberculous spondylitis, 23 patients with pyogenic spondylitis, and 24 patients with degenerative spondylopathy) after clinical, laboratory, bacteriologic, and histologic verification of diagnosis was comparatively analyzed. Current X-ray and tomographic features of tuberculous spondylitis are relatively equal thoracic and lumbosacral spine segments localization, with more than two adjacent vertebrae involvement in 22,6±7,5% of cases, the collapse of the vertebra(s) in 35.5 ± 8.6% of cases, unclear or osteoporotic border of bone tissue around TB focus in 64.5 ± 8.6%, formation of abscesses in 74.2±7.9% and their subligamentous spread to more than two vertebrae in 25,8±7,9% of cases, intact intervertebral disc in 16.1 ± 6.6% of cases, and specific process in the lungs in 48.4 ± 9.0% of cases. Keywords Tuberculous spondylitis, Pyogenic spondylitis, X-ray and tomographic features identify differential diagnostic features of tuberculous 1. Introduction spondylitis (TS). X-ray and tomographic (MRI and CT) methods of examination play a leading role in the diagnosis of 3. Materials and Methods tuberculous (TB) lesions of the spine [1,2,3]. Features of radiological changes of spine TB depend on The study was conducted at the bone and joint TB the activity and duration of the specific process [1,2]. -

Neurological Impairment in a Patient with Concurrent Cervical Disc Herniation and POEMS Syndrome

European Spine Journal (2019) 28 (Suppl 2):S51–S55 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-019-05914-5 CASE REPORT Neurological impairment in a patient with concurrent cervical disc herniation and POEMS syndrome Tingxian Ling1 · Limin Liu1 · Yueming Song1 · Shilian Zhou1 · Chunguang Zhou1 Received: 24 July 2018 / Revised: 16 December 2018 / Accepted: 9 February 2019 / Published online: 13 February 2019 © Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Purpose POEMS syndrome is a rare clonal plasma cell disease characterized by polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopa- thy, M protein, and skin changes. We report a rare case of neurological impairment in patients with concurrent cervical disc herniation and POEMS syndrome. Methods A patient presented to a local hospital with C3/4 and C4/5 disc herniation, apparent spinal cord compression con- comitant with neurological signs, and concurrent POEMS syndrome. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion was performed. Results The limb numbness was only slightly alleviated, and 10 days postoperatively the patient complained of muscle weak- ness of the extremities and was referred to our hospital. The patients exhibited non-typical neurological signs and an enlarged liver and spleen that could not be explained. Electroneuromyography and immunofxation electrophoresis produced abnormal results. We diagnosed concurrent POEMS syndrome, for which drug therapy was prescribed. The patient’s symptoms receded. Conclusion Patients presenting with cervical spondylopathy and non-typical neurological signs and symptoms or other systemic problems should be evaluated for the presence of concurrent disease and ruled out diferential diagnoses. Keywords Neurological impairment · POMES syndrome · Cervical disc herniation · Cervical spondylosis Introduction a chronic demyelinating autoimmune disease that has symp- toms similar to those associated with myelopathy: spasticity, Cervical disc herniation is a common spinal disorder that sensory disturbances, gait ataxia, weakness. -

ICD-9 to ICD-10 Mapping Tool Courtesy Of: the Paperwork Project

ICD-9 to ICD-10 Mapping Tool Courtesy of: The Paperwork Project Spinal Subluxation ICD-9 ICD-10 M99.00 Segmental and somatic dysfunction, Head region (occipito-cervical) 739.0 Segmental and somatic dysfunction, Head region (occipito-cervical) M99.10 Subluxation complex (vertebral), Head region M99.01 Segmental and somatic dysfunction, Cervical region 739.1 Segmental and somatic dysfunction, Cervical region M99.11 Subluxation complex (vertebral), Cervical region M99.02 Segmental and somatic dysfunction, Thoracic region 739.2 Segmental and somatic dysfunction, Thoracic region M99.12 Subluxation complex (vertebral), Thoracic region M99.03 Segmental and somatic dysfunction, Lumbar region 739.3 Segmental and somatic dysfunction, Lumbar region M99.13 Subluxation complex (vertebral), Lumbar region M99.04 Segmental and somatic dysfunction, Sacral region 739.4 Segmental and somatic dysfunction, Sacral region M99.14 Subluxation complex (vertebral), Sacral region M99.05 Segmental and somatic dysfunction, Sacroiliac, hip, pubic regions 739.5 Segmental and somatic dysfunction, Sacroiliac, hip, pubic regions M99.15 Subluxation complex (vertebral), Pelvic region 839.08 Closed dislocation, Multiple cervical vertebra (injury) S13.101_ Dislocation of unspecified cervical vertebra (injury) ** 839.20 Closed dislocation, Lumbar vertebra (injury) S33.101_ Dislocation of unspecified lumbar vertebra (injury) ** 839.21 Closed dislocation, Thoracic vertebra (injury) S23.101_ Dislocation of unspecified thoracic vertebra (injury) ** 839.42 Closed dislocation, Sacrum, -

IN the UNITED STATES COURT of FEDERAL CLAIMS OFFICE of SPECIAL MASTERS No

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF FEDERAL CLAIMS OFFICE OF SPECIAL MASTERS No. 10-565V Filed: June 11, 2014 For Publication * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * MEGAN L. GODFREY, * HPV Vaccine; Gardasil; Juvenile * Ankylosing Spondylitis; JAS; Petitioner, * Causation-in-Fact; Expert; v. * Qualifications. * SECRETARY OF HEALTH * AND HUMAN SERVICES, * * Respondent. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Milton Clay Ragsdale, IV, Ragsdale LLC, Birmingham, AL, for petitioner. Jennifer Reynaud, U.S. Department of Justice, Washington, DC, for respondent. DECISION1 Vowell, Chief Special Master: On August 20, 2010, Megan Godfrey [“petitioner”] filed a petition for compensation under the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program, 42 U.S.C. §300aa-10, et seq.2 [the “Vaccine Act” or “Program”]. The petition alleged that the human papillomavirus [“HPV”] and meningococcal conjugate vaccines Ms. Godfrey received on August 22, 2007, caused her to develop juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Petition at 1-2. 1 Because this decision contains a reasoned explanation for my action in this case, it will be posted on the United States Court of Federal Claims’ website, in accordance with the E-Government Act of 2002, Pub. L. No. 107-347, 116 Stat. 2899, 2913 (Dec. 17, 2002). As provided by Vaccine Rule 18(b), each party has 14 days within which to request redaction “of any information furnished by that party: (1) that is a trade secret or commercial or financial in substance and is privileged or confidential; or (2) that includes medical files or similar files, the disclosure of which would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of privacy.” Vaccine Rule 18(b). Otherwise, the entire decision will be available to the public. 2 National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act of 1986, Pub. -

Low Back Pain: a Pathway to Prioritisation

National Health Committee – Low Back Pain: A Pathway to Prioritisation National Health Committee Low Back Pain: A Pathway to Prioritisation Page 1 National Health Committee – Low Back Pain: A Pathway to Prioritisation National Health Committee (NHC) The National Health Committee (NHC) is an independent statutory body charged with prioritising new and existing health technologies and making recommendations to the Minister of Health. It was reformed in 2011 to establish evaluation systems that would provide the New Zealand people and the health sector with greater value for money invested in health. The NHC Executive is the secretariat that supports the Committee. The NHC Executive’s primary objective is to provide the Committee with sufficient information for it to make decisions regarding prioritisation and reprioritisation of interventions and services. They do this through a range of evidence-based products chosen according to the nature of the decision required and timeframe within which decisions need to be made. The New Zealand Government has asked that all new diagnostic and treatment (non-pharmaceutical) services, and significant expansions of existing services, are to be referred to the NHC. In August 2011 the NHC was appointed with new Terms of Reference and a mandate to establish the capacity to assess new and existing health technologies. Its objectives (under Section 4.2 of its Terms of Reference – www.nhc.health.govt.nz) include contributing to improved value for money and fiscal sustainability in the health and disability sector by: providing timely advice and recommendations about relative cost-effectiveness based on the best available evidence; providing advice and recommendations which influence the behaviour of decision makers including clinicians and other health professionals; providing advice and recommendations which are reflected in resource allocation at national, regional and local levels; and contributing to tangible reductions in the use of ineffective interventions and improved targeting to those most likely to benefit. -

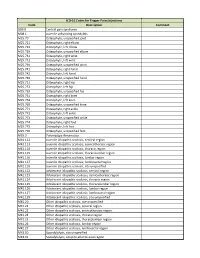

ICD-10 Codes for Trigger Point Injections

ICD-10 Codes for Trigger Point Injections Code Description Comment G89.0 Central pain syndrome M08.1 Juvenile ankylosing spondylitis M25.70 Osteophyte, unspecified joint M25.721 Osteophyte, right elbow M25.722 Osteophyte, left elbow M25.729 Osteophyte, unspecified elbow M25.731 Osteophyte, right wrist M25.732 Osteophyte, left wrist M25.739 Osteophyte, unspecified wrist M25.741 Osteophyte, right hand M25.742 Osteophyte, left hand M25.749 Osteophyte, unspecified hand M25.751 Osteophyte, right hip M25.752 Osteophyte, left hip M25.759 Osteophyte, unspecified hip M25.761 Osteophyte, right knee M25.762 Osteophyte, left knee M25.769 Osteophyte, unspecified knee M25.771 Osteophyte, right ankle M25.772 Osteophyte, left ankle M25.773 Osteophyte, unspecified ankle M25.774 Osteophyte, right foot M25.775 Osteophyte, left foot M25.776 Osteophyte, unspecified foot M35.3 Polymyalgia rheumatica M41.112 Juvenile idiopathic scoliosis, cervical region M41.113 Juvenile idiopathic scoliosis, cervicothoracic region M41.114 Juvenile idiopathic scoliosis, thoracic region M41.115 Juvenile idiopathic scoliosis, thoracolumbar region M41.116 Juvenile idiopathic scoliosis, lumbar region M41.117 Juvenile idiopathic scoliosis, lumbosacral region M41.119 Juvenile idiopathic scoliosis, site unspecified M41.122 Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, cervical region M41.123 Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, cervicothoracic region M41.124 Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, thoracic region M41.125 Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, thoracolumbar region M41.126 Adolescent idiopathic -

Ninth International Congress on Spondyloarthritis

Ninth International Congress on Spondyloarthritis October 23–25, 2014 Gent, Belgium Presidents Martin Rudwaleit Dept. of Internal Medicine and Rheumatology Klinikum Bielefeld Bielefeld, Germany John D. Reveille Division of Rheumatology The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston Houston, USA Local Organisers Herman Mielants Dirk Elewaut Filip Van den Bosch Dept. of Rheumatology, University of Gent Gent, Belgium Abstracts Page no. Invited Lectures (INV1 – INV25) 766 Oral Presentations (O1 – O12) 771 Short Oral Presentations (SO1 – SO5) 775 Poster Presentations (P1 – P182) 776 Author Index 835 Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology 2014; 32: 765-838. Invited Lectures Ninth International Congress on Spondyloarthritis Invited Lectures (SCORE), which are based on CV risk factors. Statin and/or antihypertensive treatment is then only initiated above a certain threshold, e.g. a 10-year CV mor- tality risk of 10% or more or a 10 year CV morbidity of 20% or more. EULAR recommendations for CV-RM in patients with IJD advised yearly CV INV1 risk screening For RA it is recommended to adapt existing risk functions, such as SCORE, by a multiplier of 1.5 to achieve a more appropriate estimation of THE INTESTINAL MICROBIOME AND THE IMMUNE SYSTEM the 10 years CV risk (9). Obviously, effective suppression on the inflammatory process is necessary to further decrease the CV-risk. For SLE it is recommended Eberl G. the LDL-cholesterol levels should below 2.6 mmol/L and blood pressure levels Lymphoid Tissue Development Unit, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France be lower than 130/80 mmHg. When there are no contraindications, aspirin should be given to patients with a history of CV events (including myocardial infarction, RORγt+ T cells and RORγt+ innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) play central roles in angina or stroke), the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies, hypertension, dia- the development of the immune system, in homeostasis of the host with its sym- betes, hypercholesterolemia, or smoking (10). -

Coding Guideline for Chiropractic Services CPT © Codes Criteria For

Coding Guideline for Chiropractic Services CPT © Codes 98940 Chiropractic manipulative treatment (cmt); spinal, 1-2 regions 98941 Chiropractic manipulative treatment (cmt); spinal, 3-4 regions 98942 Chiropractic manipulative treatment (cmt); spinal, 5 regions 72020 Radiologic examination, spine, singe view, specify level 72040 Radiologic examination, spine, cervical; 2 or 3 views 72050 Radiologic examination, spine, cervical; 4 or 5 views 72052 Radiologic examination, spine, cervical; 6 or more views 72070 Radiologic examination, spine, thoracic, 2 views 72072 Radiologic examination, spine, thoracic, 3 views 72074 Radiologic examination, spine, thoracic, minimum of 4 views 72080 Radiologic examination, spine, thoracolumbar, 2 views 72100 Radiologic examination, spine, lumbosacral; 2 or 3 views 72110 Radiologic examination, spine, lumbosacral; minimum of 4 views 72114 Radiologic examination, spine, lumbosacral; complete, including bending views, minimum of 6 views. 72120 Radiologic examination, spine, lumbosacral; bending views only, 2 or 3 views 72220 Radiologic examination, sacrum and coccyx, minimum of 2 views Criteria for Coverage Payment for manual manipulation of the spine is limited to one manipulation per day and may not exceed 12 manipulations per calendar year. Effective for dates of service on or after January 1, 2005, North Dakota Medicaid will allow reimbursement to chiropractors for Evaluation and Management (E/M) office and other outpatient Services – New Patient (99201-99203). These E/M services may be billed in addition to the chiropractic manipulative treatment (98940-98942) ONLY when the patient has not received any professional (face-to-face) services from the chiropractor, or another chiropractor of the same group practice, within the past three years. Payment for x-rays may not exceed two (2) per year and are limited to radiological examinations of the full spine; the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and lumbosacral areas of the spine. -

The Evolution of Interlaminar Endoscopic Spine Surgery

512 Review Article on Full-endoscopic Spine Surgery The evolution of interlaminar endoscopic spine surgery Kuo-Tai Chen1,2, Hussam Jabri1, Yadhu K. Lokanath1, Myung-Soo Song1, Jin-Sung Kim1 1Department of Neurosurgery, Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, South Korea; 2Department of Neurosurgery, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chia-Yi Contributions: (I) Conception and design: JS Kim; (II) Administrative support: None; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: None; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: None; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: None; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Jin-Sung Kim, MD, PhD. Department of Neurosurgery, Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea, 222, Banpo- daero, Seocho-gu, Seoul, South Korea. Email: [email protected]; [email protected]. Abstract: Due to the aging population, patients required spinal surgery for degenerative spondylopathy is increasing. With the advent of surgical instruments and techniques, minimally invasive spine surgery is prevalent worldwide. Besides microscopic techniques, endoscopic spine surgery has gotten attention gradually in this surgical field for the past two decades. There are two essential approaches developed currently, including transforaminal and interlaminar approach. These innovative equipment and skills promote the progression of endoscopic surgery from discectomy to decompression of spinal stenosis. Meanwhile, they also opened up the application of endoscopic surgery in a complicated situation. From the perspective of emerging technologies and techniques, the authors will review the evolution and describe the prospects of the interlaminar endoscopic spine surgery (IESS). Keywords: Endoscopic spine surgery; interlaminar; minimally invasive spine surgery; endoscopic spine decompression Submitted Aug 20, 2019. -

Infectious Spinal Pathology Mimicking Infections

Kumar et al. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders (2017) 18:244 DOI 10.1186/s12891-017-1608-z REVIEW Open Access Magnetic resonance imaging of bacterial and tuberculous spondylodiscitis with associated complications and non- infectious spinal pathology mimicking infections: a pictorial review Yogesh Kumar1, Nishant Gupta2, Avneesh Chhabra3, Takeshi Fukuda4, Neetu Soni5 and Daichi Hayashi1,6* Abstract Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging plays an important role in the evaluation of bacterial and tuberculous spondylodiscitis and associated complications. Owing to its high sensitivity and specificity, it is a powerful diagnostic tool in the early diagnosis of ongoing infections, and thus provides help in prompt initiation of appropriate, therapy which may be medical or surgical, by defining the extent of involvement and detection of complications such as epidural and paraspinal abscesses. More specifically, MR imaging helps in differentiating bacterial from tuberculous infections and enables follow up of progression or resolution after appropriate treatment. However, other non-infectious pathology can demonstrate similar MR imaging appearances and one should be aware of these potential mimickers when interpreting MR images. Radiologists and other clinicians need to be aware of these potential mimics, which include such pathologies as Modic type I degenerative changes, trauma, metastatic disease and amyloidosis. In this pictorial review, we will describe and illustrate imaging findings of bacterial and tuberculous spondylodiscitis, their complications and non-infectious pathologies that mimic these spinal infections. Keywords: Spine, Infection, Abscess, MRI, Spondylitis, Discitis Background be aware of these potential mimickers when interpreting Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging plays an important MR images [6–10]. Radiologists and referring clinicians role in the evaluation of bacterial and tuberculous spon- need to be aware of these potential mimics, which in- dylodiscitis. -

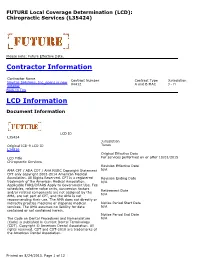

FUTURE Local Coverage Determination for Chiropractic

FUTURE Local Coverage Determination (LCD): Chiropractic Services (L35424) Please note: Future Effective Date. Contractor Information Contractor Name Contract Number Contract Type Jurisdiction Novitas Solutions, Inc. opens in new 04412 A and B MAC J - H window Back to Top LCD Information Document Information LCD ID L35424 Jurisdiction Original ICD-9 LCD ID Texas L34816 Original Effective Date LCD Title For services performed on or after 10/01/2015 Chiropractic Services Revision Effective Date AMA CPT / ADA CDT / AHA NUBC Copyright Statement N/A CPT only copyright 2002-2014 American Medical Association. All Rights Reserved. CPT is a registered Revision Ending Date trademark of the American Medical Association. N/A Applicable FARS/DFARS Apply to Government Use. Fee schedules, relative value units, conversion factors Retirement Date and/or related components are not assigned by the N/A AMA, are not part of CPT, and the AMA is not recommending their use. The AMA does not directly or indirectly practice medicine or dispense medical Notice Period Start Date services. The AMA assumes no liability for data N/A contained or not contained herein. Notice Period End Date The Code on Dental Procedures and Nomenclature N/A (Code) is published in Current Dental Terminology (CDT). Copyright © American Dental Association. All rights reserved. CDT and CDT-2010 are trademarks of the American Dental Association. Printed on 8/24/2015. Page 1 of 12 UB-04 Manual. OFFICIAL UB-04 DATA SPECIFICATIONS MANUAL, 2014, is copyrighted by American Hospital Association (“AHA”), Chicago, Illinois. No portion of OFFICIAL UB-04 MANUAL may be reproduced, sorted in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior express, written consent of AHA.” Health Forum reserves the right to change the copyright notice from time to time upon written notice to Company.