Translation Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cities, Rural Migrants and the Urban Poor: Issues of Violence and Social Justice

Cities, Rural Migrants and the Urban Poor: Issues of Violence and Social Justice Research Briefs with Policy Implications Published by: Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group GC-45, Sector-III, First Floor Salt Lake City Kolkata-700106 India Web: http://www.mcrg.ac.in Printed by: Graphic Image New Market, New Complex, West Block 2nd Floor, Room No. 115, Kolkata-87 The publication is a part of the project 'Cities, Rural Migrants and the Urban Poor'. We thank all the researchers, discussants and others who participated in the project and in the project related events. We also thank the MCRG team for their support. The support of the Ford Foundation is gratefully acknowledged. Content Introduction 1 Part One: Research Briefs Section I: Kolkata 5 • Taking Refuge in the City: Migrant Population and Urban Management in Post-Partition Calcutta by Kaustubh Mani Sengupta • Urban Planning, Settlement Practices and Issues of Justice in Contemporary Kolkata by Iman Kumar Mitra • Migrant Workers and Informality in Contemporary Kolkata by Iman Kumar Mitra • A Study of Women and Children Migrants in Calcutta by Debarati Bagchi and Sabir Ahmed • Migration and Care-giving in Kolkata in the Age of Globalization by Madhurilata Basu Section II: Delhi 25 • The Capital City: Discursive Dissonance of Law and Policy by Amit Prakash • Terra Firma of Sovereignty: Land, Acquisition and Making of Migrant Labour by Mithilesh Kumar • ‘Transient’ forms of Work and Lives of Migrant Workers in ‘Service’ Villages of Delhi by Ishita Dey Section III: Mumbai 35 • Homeless Migrants -

From Little Tradition to Great Tradition: Canonising Aithihyamala NIVEA THOMAS K S

From Little Tradition to Great Tradition: Canonising Aithihyamala NIVEA THOMAS K S. ARULMOZI Abstract In an attempt to reinvent the tradition of Kerala in the light of colonial modernity, Kottarathil Sankunni collected and transcribed the lores and legends of Kerala in his work Aithihyamala in 1909. When the legends were textualised, Sankunni attributed certain literary values to the narratives to legitimise the genre. As it was a folk appropriation by a scholarly elite like Sankunni who had received English education during the colonial period, the legends moved from folk tradition to classical tradition. In their transition from Little Tradition to Great Tradition, the legends underwent huge transformation in terms of form, content, language, context and narrative style. The text became fixed, stable and structured and was eventually subjected to a canon. However, when one perceives Aithihyamala (1909) as the ‘authentic’ and the ‘final’ version of the legends in Kerala, one is neglecting and silencing the multiple oral versions and folk tradition that had been existing since the pre-literate period. The current study attempts to trace the transformation undergone by the text when it moved towards the direction of a literary canon. Keywords: Legends Transcription, Great Tradition, Little Tradition, Literary Canon. Introduction Aithihyamala, a collection of lores and legends of Kerala was compiled by Kottarathil Sankunni in Bhashaposhini magazine in the beginning of the twentieth century. In his preface to DOI: 10.46623/tt/2020.14.1.ar4 Translation Today, Volume 14, Issue 1 Nivea Thomas K & S. Arulmozi Aithihyamala (1909) which comprises 126 legends, Sankunni (2017: 89) states that the text had been harshly criticised by an anonymous writer on the grounds of its casual nature. -

Unit-1 T. S. Eliot : Religious Poems

UNIT-1 T. S. ELIOT : RELIGIOUS POEMS Structure 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 ‘A Song for Simeon’ 1.3 ‘Marina’ 1.4 Let us sum up 1.5 Review Questions 1.6 A Select Bibliography 1.0 Objectives The present unit aims at acquainting you with some of T.S. Eliot’s poems written after his confirmation into the Anglo-Catholic Church of England in 1927. With this end in view, this unit takes up a close reading of two of his ‘Ariel Poems’ and focuses on some traits of his religious poetry. 1.1 Introduction Thomas Stearns Eliot was born on 26th September, 1888 at St. Louis, Missouri, an industrial city in the center of the U.S.A. He was the seventh and youngest child of Henry Ware Eliot and Charlotte Champe Stearns. He enjoyed a long life span of more than seventy-five years. His period of active literary production extended over a period of forty-five years. Eliot’s Calvinist (Puritan Christian) ancestors on father’s side had migrated in 1667 from East Coker in Somersetshire, England to settle in a colony of New England on the eastern coast of North America. His grandfather, W.G. Eliot, moved in 1834 from Boston to St. Louis where he established the first Unitarian Church. His deep academic interest led him to found Washington University there. He left behind him a number of religious writings. Eliot’s mother was an enthusiastic social worker as well as a writer of caliber. His family background shaped his poetic sensibility and contributed a lot to his development as a writer, especially as a religious poet. -

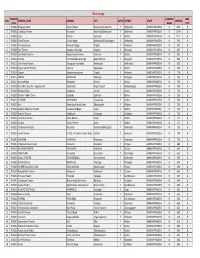

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

Koel Mallick Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

Koel Mallick 电影 串行 (大全) 100% Love https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/100%25-love-4545961/actors Bandhan https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/bandhan-4854552/actors Hero https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/hero-21161311/actors Love https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/love-6690235/actors Eri Naam Prem https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/eri-naam-prem-16248318/actors Chore Chore Mastuto Bhai https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/chore-chore-mastuto-bhai-5105002/actors Sagardwipey Jawker Dhan https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/sagardwipey-jawker-dhan-64768666/actors Neel Akasher Chadni https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/neel-akasher-chadni-6986698/actors Shubhodrishti https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/shubhodrishti-16254219/actors Rawkto Rawhoshyo https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/rawkto-rawhoshyo-85796147/actors Shikar https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/shikar-16254147/actors Hemlock society https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/hemlock-society-5712303/actors Chander Bari https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/chander-bari-5071009/actors Saat Paake Bandha https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/saat-paake-bandha-7395714/actors MLA Fatakeshto https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/mla-fatakeshto-6716513/actors Premi No.1 https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/premi-no.1-7240259/actors Yuddho https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/yuddho-8060215/actors Shesh Theke Shuru https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/shesh-theke-shuru-63859758/actors -

À¸Œà¸¥À¸‡À¸²À¸™À¸ À¸²À¸Žà¸¢À¸™À¸•À¸£À¹œ)

Paran Bandopadhyay ภาพยนตร์ รายà¸à ¸²à¸£ (ผลงานภาพยนตร์) Arshinagar https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/arshinagar-19954324/actors Brake Fail https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/brake-fail-4956021/actors Bhootchakra Pvt. Ltd. https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/bhootchakra-pvt.-ltd.-65047969/actors Open Tee Bioscope https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/open-tee-bioscope-19263869/actors Feluda: 50 Years of Ray's https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/feluda%3A-50-years-of-ray%27s-detective- Detective 65555937/actors Bhoot Bhooturey Samuddurey https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/bhoot-bhooturey-samuddurey-18611352/actors Banchha Elo Phire https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/banchha-elo-phire-27536734/actors Abar Basanta Bilap https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/abar-basanta-bilap-55390488/actors Ashchorjyo Prodeep https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/ashchorjyo-prodeep-16242689/actors Hochheta Ki https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/hochheta-ki-13522751/actors Obhishopto Nighty https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/obhishopto-nighty-15731589/actors Surjo Prithibir Chardike Ghore https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/surjo-prithibir-chardike-ghore-77896615/actors Proloy https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/proloy-20819662/actors Cinemawala https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/cinemawala-24514706/actors Monchora https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/monchora-21998229/actors Abby Sen https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/abby-sen-21426976/actors -

Annual Report 2018 – 2019 N C E R T

NCERT Annual Report 2018 – 2019 N C E R T Annual Report 2018 –2019 February 2020 Magha 1941 PD 5H BS © National Council of Educational Research and Training, 2020 Published at the Publication Division, by the Secretary, National Council of Educational Research and Training, Sri Aurobindo Marg, New Delhi – 110 016 and printed at Pushpak Press Private Limited, B-3/1, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-II, New Delhi – 110 020 Foreword The Annual Report presents a glimpse of initiatives undertaken by the National Council of Educational Research and Training for the year 2018–19. NCERT, the apex body working in the area of school education, provides leadership, strengthens the national education system and caters to the needs of the States and UTs. The Council has emerged as a guiding force to buildup a progressive system of education that can help in utilising the human resources as a dividend to the country. The NCERT Annual Report 2018–19, to take its mission forward, provides insights into the concerns, priorities and activities of its constituent units. The Council has undertaken various research studies, development activities, capacity building programmes and extension activities to reach out every child located in the remotest corner of the country. It has brought out the district wise reports of the National Achievement Survey and more than 500 publications, which includes textbooks, workbooks, supplementary readers, teacher guides, laboratory manuals, source books on assessment and educational journals. The Council has further ventured into development of online courses, learning outcomes for the secondary stage, curriculum frameworks for four-year integrated B.Ed, ICT curriculum, vocational education curricular materials, educational media programmes, handbooks for teachers working in special training centres for Out of School Children (OoSC), student workbooks, etc. -

Haryanvi Caste Hindus

Haryanvi Caste Hindus indigineous church, with the exception of a few lower Pahari Panjabi caste groups (Dalits), among Nepali Haryanvi which several hundred fel- Rajasthani Hindi lowships have been estab- lished. Unfortunately, this response among the Dalits has only further served to alienate the upper caste Quick Facts majority peoples. There Population: 14,000,000 Indigenous Church Development Stage have been recent attempts Major Subgroups: 1 2 3 4 5 to reach the Jat, which make Jat- 3,700,000 up around one fourth of Chamar- 2,000,000 Classes A, B, C Ratio of non-Christians the Haryanvi population. Brahman- 1,500,000 for every 1 Christian However, the response has Rajput- 1,400,000 1 B-4% been limited, partially due Religion: Hindu 1,400 Believers: 0.07% A-<1% to the fact that the mission- Scriptures: Portions C-95% aries are mostly Dalits from Ministry Tools: JG South India. C Status: 3 M Status: 2 Class A- Are members of a Culturally Relevant Church MS Subgroups: 40+ Class B- Have close accss to a CRC, but have not yet joined How to Pray: Class C- Have no reasonable or close access to a CRC Pray for an effective wit- ness among the Haryanvi Identity: Over 40 Hindu peoples use imbalance of male to female ratios (11 upper castes that will bring the Haryanvi language as their mother- to 9 ratio) due to the selective abortions the gospel to these peoples tongue. They are the majority group of female babies. As a result, there is in ways that are sensitive and in the state of Haryana, with minority now a shortage of available brides, lead- relevant to their culture. -

Jihadist Violence: the Indian Threat

JIHADIST VIOLENCE: THE INDIAN THREAT By Stephen Tankel Jihadist Violence: The Indian Threat 1 Available from : Asia Program Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 www.wilsoncenter.org/program/asia-program ISBN: 978-1-938027-34-5 THE WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS, established by Congress in 1968 and headquartered in Washington, D.C., is a living national memorial to President Wilson. The Center’s mission is to commemorate the ideals and concerns of Woodrow Wilson by providing a link between the worlds of ideas and policy, while fostering research, study, discussion, and collaboration among a broad spectrum of individuals concerned with policy and scholarship in national and interna- tional affairs. Supported by public and private funds, the Center is a nonpartisan insti- tution engaged in the study of national and world affairs. It establishes and maintains a neutral forum for free, open, and informed dialogue. Conclusions or opinions expressed in Center publications and programs are those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individuals or organizations that provide financial support to the Center. The Center is the publisher of The Wilson Quarterly and home of Woodrow Wilson Center Press, dialogue radio and television. For more information about the Center’s activities and publications, please visit us on the web at www.wilsoncenter.org. BOARD OF TRUSTEES Thomas R. Nides, Chairman of the Board Sander R. Gerber, Vice Chairman Jane Harman, Director, President and CEO Public members: James H. -

Real Image THEATRE COMPANY WEB S.No

Real Image THEATRE COMPANY WEB S.No. THEATRE_NAME ADDRESS CITY ACTIVE DISTRICT STATE SEATING CODE NAME CODE 1 TH0001 Bhujanga 70mm Shapure Nagar Hyderabad (Jedimetla) Y Hyderabad ANDHRA PRADESH RI 1311 0 2 TH0002 Laxmikala Theatre Moosapet Hyderabad(Moosapet) Y Hyderabad ANDHRA PRADESH RI 1189 0 3 TH0003 Sarat Krishna Gudivada Y Krishna ANDHRA PRADESH RI 1112 0 4 TH0006 Geeta Theatre Chanda Nagar Hyderabad (Chandanagar) Y Hyderabad ANDHRA PRADESH RI 962 0 5 TH0007 Srinivasa Deluxe Mahendra Nagar Ongole Y Prakasam ANDHRA PRADESH RI 900 0 6 TH0009 Devi Theatre Janagoan, Warangal Jangaon Y Warangal ANDHRA PRADESH RI 837 0 7 TH0010 Sree Balaji Theatres Satyanarayana Puram Gudivada Y Krishna ANDHRA PRADESH RI 833 0 8 TH0011 Ashoka Hanumakonda, Warangal Hanumakonda Y Warangal ANDHRA PRADESH RI 830 0 9 TH0012 Sree Prema Theatre Tukkuguda Hyderabad Hyderabad Y Hyderabad ANDHRA PRADESH RI 800 0 10 TH0013 Vijaya Lakshmi Theatre Kaanuru Vijayawada Y Krishna ANDHRA PRADESH RI 786 0 11 TH0014 Satyam Satyanarayanapuram Ongole Y Prakasam ANDHRA PRADESH RI 779 0 12 TH0015 NATRAJ WARANGAL Warangal Y Warangal ANDHRA PRADESH RI 766 0 13 TH0017 Krishna Mahal Kothapeta Guntur Y Guntur ANDHRA PRADESH RI 750 0 14 TH0018 Ravi 70mm A/c DTS - Nagarkarnool Sripur Road Nagarkarnool Y Mehboobnagar ANDHRA PRADESH RI 750 0 15 TH0019 Bhaskar Palace Kothapeta Guntur Y Guntur ANDHRA PRADESH RI 740 0 16 TH0020 Bhaskar Talkies 70mm Gudivada Gudivada Y Krishna ANDHRA PRADESH RI 738 0 17 TH0021 ALANKAR VIJAYAWADA Vijayawada Y Krishna ANDHRA PRADESH RI 738 0 18 TH0022 Ravi -

Raag-Mala Music Society of Toronto: Concert History*

RAAG-MALA MUSIC SOCIETY OF TORONTO: CONCERT HISTORY* 2013 2012 2011 Praveen Sheolikar, Violin Ud. Shahid Parvez, Sitar Pt. Balmurli Krishna, Vocal Gurinder Singh, Tabla Subhajyoti Guha, Tabla Pt. Ronu Majumdar, Flute Arati Ankalikar Tikekar, Vocal Ud. Shujaat Khan, Sitar Kishore Kulkarni, Tabla Abhiman Kaushal, Tabla Ud. Shujaat Khan, Sitar Abhiman Kaushal, Tabla Anand Bhate, Vocal Vinayak Phatak, Vocal Bharat Kamat, Tabla Enakshi, Odissi Dance The Calcutta Quartet, Violin, Suyog Kundalka, Harmonium Tabla & Mridangam Milind Tulankar, Jaltrang Hidayat Husain Khan, Sitar Harvinder Sharma, Sitar Vineet Vyas, Tabla Ramdas Palsule, Tabla Warren Senders, Lecture- Raja Bhattacharya, Sarod Demonstration and Vocal Shawn Mativetsky, Tabla Raya Bidaye, Harmoium Ravi Naimpally, Tabla Gauri Guha, Vocal Ashok Dutta, Tabla Luna Guha, Harmonium Alam Khan, Sarod Hindole Majumdar, Tabla Sandipan Samajpati, Vocal Raya Bidaye, Harmonium Hindole Majumdar, Tabla Ruchira Panda, Vocal Pandit Samar Saha, Tabla Anirban Chakrabarty, Harmonium 2010 2009 2008 Smt. Ashwini Bhide Deshpande, Smt. Padma Talwalkar, Vocal Pt. Vishwa Mohan Bhatt, Mohan Vocal Rasika Vartak, Vocal Veena Vishwanath Shirodkar, Tabla Utpal Dutta, Tabla Subhen Chatterji, Tabla Smt. Seema Shirodkar, Suyog Kundalkar, Harmonium Heather Mulla, Tanpura Harmonium Anita Basu, Tanpura Milind Tulankar, Jaltarang Pt. Rajan Mishra, Vocal Sunit Avchat, Bansuri Pt. Sajan Mishra, Vocal Tejendra Majumdar, Sarod Ramdas Palsule, Tabla Subhen Chatterji, Tabla Abhijit Banerjee,Tabla Sanatan Goswami, Harmonium Kiran Morarji, Tanpura Irshad Khan, Sitar Manu Pal, Tanpura Subhojyoti Guha, Tabla Aparna Bhattacharji, Tanpura Aditya Verma, Sarod Ramneek Singh, Vocal Hindol Majumdar, Tabla Pt. Ronu Majumdar, Flute Won Joung Jin, Kathak Ramdas Palsule, Tabla Amaan Ali Khan, Sarod Rhythm Riders, Tabla Bharati, tanpura Ayaan Ali Khan, Sarod Vineet Vyas, Tabla 1 RAAG-MALA MUSIC SOCIETY OF TORONTO: CONCERT HISTORY* 2010 Cont. -

Rudra 22 2019 English AAAA.Pmd

22/2019 Question Booklet Question Booklet Alpha Code A Serial Number Total Number of Questions : 100 Time : 75 Minutes Maximum Marks : 100 INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES 1. The question paper will be given in the form of a Question Booklet. There will be four versions of question booklets with question booklet alpha code viz. A, B, C & D. 2. The Question Booklet Alpha Code will be printed on the top left margin of the facing sheet of the question booklet. 3. The Question Booklet Alpha Code allotted to you will be noted in your seating position in the Examination Hall. 4. If you get a question booklet where the alpha code does not match to the allotted alpha code in the seating position, please draw the attention of the Invigilator IMMEDIATELY. 5. The Question Booklet Serial Number is printed on the top right margin of the facing sheet. If your question booklet is un-numbered, please get it replaced by new question booklet with same alpha code. 6. The question booklet will be sealed at the middle of the right margin. Candidate should not open the question booklet, until the indication is given to start answering. 7. Immediately after the commencement of the examination, the candidate should check that the question booklet supplied to him contains all the 100 questions in serial order. The question booklet does not have unprinted or torn or missing pages and if so he/she should bring it to the notice of the Invigilator and get it replaced by a complete booklet with same alpha code.