Don Piccard Inducted 2002

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tradition Well Served Well Tradition

TRADITION WELL SERVED TRADITION 2016 1 A LETTER FROM THE CHAIRMAN nniversaries are a time to pause and reflect. As we review The new company, as well as owning hotels in Hong Kong, now our past, it is important to recognise the many milestones had full control over Shanghai’s Astor House and Palace Hotel. that have shaped our company, and to remember the Later additions were The Majestic in Shanghai and the Grand Hotel Aindividuals whose legacies have ensured the beneficial role that we des Wagons-Lits in Peking. have played in Hong Kong’s success story. Plans were soon afoot for a third hotel to be built on the Our history begins in the latter part of the nineteenth century: Kowloon peninsula – at the time a sleepy backwater. Although six years after Kowloon was ceded to Great Britain, and 32 years originally a government project to take advantage of the transport before the New Territories were leased. Sedan chairs and rickshaws links afforded by the railway terminus and the nearby quays of were the transport of the day. Kowloon, it was Taggart’s vision and determination that ensured The 1860s were a period of growing interest in the Far East The Peninsula Hotel, when opened, would become “the finest hotel and, thanks to popular literature at the time, Hong Kong held a east of Suez”. Due to a number of construction challenges, this particular fascination for travellers attracted to the orient. The project was nearly abandoned, but Taggart persisted despite growth of tourism was facilitated by entrepreneurs such as Thomas objections from shareholders who believed any hotel built in Cook who arranged fledging tour services for independent travellers Kowloon would be a “white elephant”. -

Great Cloud of Witnesses.Indd

A Great Cloud of Witnesses i ii A Great Cloud of Witnesses A Calendar of Commemorations iii Copyright © 2016 by The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America Portions of this book may be reproduced by a congregation for its own use. Commercial or large-scale reproduction for sale of any portion of this book or of the book as a whole, without the written permission of Church Publishing Incorporated, is prohibited. Cover design and typesetting by Linda Brooks ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-962-3 (binder) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-966-1 (pbk.) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-963-0 (ebook) Church Publishing, Incorporated. 19 East 34th Street New York, New York 10016 www.churchpublishing.org iv Contents Introduction vii On Commemorations and the Book of Common Prayer viii On the Making of Saints x How to Use These Materials xiii Commemorations Calendar of Commemorations Commemorations Appendix a1 Commons of Saints and Propers for Various Occasions a5 Commons of Saints a7 Various Occasions from the Book of Common Prayer a37 New Propers for Various Occasions a63 Guidelines for Continuing Alteration of the Calendar a71 Criteria for Additions to A Great Cloud of Witnesses a73 Procedures for Local Calendars and Memorials a75 Procedures for Churchwide Recognition a76 Procedures to Remove Commemorations a77 v vi Introduction This volume, A Great Cloud of Witnesses, is a further step in the development of liturgical commemorations within the life of The Episcopal Church. These developments fall under three categories. First, this volume presents a wide array of possible commemorations for individuals and congregations to observe. -

J N CAR Conference Surveys Balloon Instrument Stabilization

NCAR Conference Surveys Balloon Instrument Stabilization If a telescope or other astronomical sensor can be lifted by a balloon above much of the earth’s atmos phere, more detailed planetary and stellar observations u»_o of various kinds are possible than can ever be achieved HO cd from the ground. In every balloon-borne experiment of this kind, however, the problems are the same: How can an astronomical sensor find and track a pinpoint target? How can the spatial orientation of the balloon platform be controlled sufficiently to allow the delicate E "e3 pointing apparatus to do its work? A considerable number of approaches have been or are being tried to solve these questions. A recent NCAR-sponsored conference brought together scien tists actively engaged in balloon-borne astronomical exploration, in order to sketch an over-all picture of the state of the art, and to accelerate progress by increasing communication among them. CONFERENCE IMPRESSIONS At the conference, held in Cambridge, Massachusetts r------i I " I in late October, some general impressions of the present state of the art emerged from descriptions of various stabilization systems: —Tracking stability to within one minute of arc is well within present capabilities. —The achievement of better-than-one-second-of-arc stability represents engineering of a high order of skill. J Nevertheless, theoretical limits of stability are much higher; even the .02 second of resolution hoped for the Stratoscope II system does not approach them. —A balloon vehicle provides a platform with excellent 0 / e ) P 5 ! stability. At float altitude, pendulum motion is usually five minutes of arc, and seldom exceeds thirty minutes. -

Holy Dying a Feminist Theologian Views Abortion

publication. and reuse for required Permission Lethal Legacy: Radwaste DFMS. / Larry Medsker Church Jeannette Piccard: Holy Dying Episcopal Alia Bozarth-Campbell • Chester Talton • Daniel Corrigan the of A Feminist Theologian Views Abortion Archives Beverly Wiidung Harrison 2020. Copyright the Left had by then turned its attention opposition to abortion is a matter of a to stopping the U.S. involvement in prurient and anti-woman bigotry. Vietnam. There was little energy and They are apparently unaware (or less vision remaining with which to choose to keep their readers unaware) tackle the tenacles of sexism. of the large numbers of feminist, Haitt and Heyward contend that progressive, and peaceful Christians sexism was the "volatile, explosive, and who oppose abortion because it is decisive" issue of the 1980 elections, violent — it is bloody — and it snuffs out precipitating the defeat of President human lives. LETTERS Carter and sundry U.S. Senators. Or is this perhaps another of those Special pleading alone would pick that "dirty little secrets"? TnTTTHll Q issue from the complex fabric of factors Ms. Juli Loesch affecting voters in late 1980. The Prolifers for Survival economy, foreign affairs, political Erie, Pa. publication. organization, money, to say nothing of regional and state-by-state differences and contributed to the liberal debacle (Iowa has never in the century re-elected a Heyward, Hiatt Respond reuse Authors' Ire Emotional Democratic Senator). And to suggest Dr. Kastner is precisely correct in his for The essay of the Revs. Suzanne Hiatt that Jimmy Carter was in the same final observation that the Right has and Carter Heyward on "Right-Wing liberal circles on women's issues as capitalized on the weariness and Religion's 'Dirty Little Secret' " Senators McGovern and Bayh is bizarre required weakness of the Left. -

AEM Update Department of Aerospace Engineering and Mechanics Winter 2014 Visiting Fulbright Scholar Reflects on Experience

AEM Update Department of Aerospace Engineering and Mechanics Winter 2014 Visiting Fulbright Scholar Reflects on Experience Visiting Fulbright Scholar Bela Distinguished McKnight University Professor Gary Balas. “We Takarics joined the University’s De- are always looking to advance our research and see this as a partment of Aerospace Engineering great opportunity to do so. The department has had a strong and Mechanics in December 2013. connection with the Hungarian Academy of Science. We truly Working as a Research Associate, benefit from the exchange of scholars between our two institu- Takarics’ interests include reduced tions. ” order modeling with a focus on aeroservoelastic vehicles and how their models vary across the flight envelope, and the application of Only three months into his stay, Takarics is highly motivated a Tensor Product model based control design to aeroservoelastic ve- by the work he has accomplished, claiming that his research hicles. Now three months into his five-month stay, Takarics says his is on the “fast track in terms of development” and expressing experience thus far has been “absolutely amazing.” interest in extending his stay for an additional four months. When asked what is attributing to this success, Takarics Prior to applying for the Fulbright Scholar explains that working in the laboratory and Program, Takarics received a Masters in Me- Since joining the AEM collaborating with other researchers has been chanical Engineering and a PhD in Control team, my research has been incredibly helpful. Theory from Budapest University of Technolo- “ gy and Economics. In 2010 he began working on the fast track in terms of “In Hungary, theoretical research can be as a Research Fellow to develop a robust and development. -

Assessing the Evolution of the Airborne Generation of Thermal Lift in Aerostats 1783 to 1883

Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research Volume 13 Number 1 JAAER Fall 2003 Article 1 Fall 2003 Assessing the Evolution of the Airborne Generation of Thermal Lift in Aerostats 1783 to 1883 Thomas Forenz Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/jaaer Scholarly Commons Citation Forenz, T. (2003). Assessing the Evolution of the Airborne Generation of Thermal Lift in Aerostats 1783 to 1883. Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.15394/ jaaer.2003.1559 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Forenz: Assessing the Evolution of the Airborne Generation of Thermal Lif Thermal Lift ASSESSING THE EVOLUTION OF THE AIRBORNE GENERATION OF THERMAL LIFT IN AEROSTATS 1783 TO 1883 Thomas Forenz ABSTRACT Lift has been generated thermally in aerostats for 219 years making this the most enduring form of lift generation in lighter-than-air aviation. In the United States over 3000 thermally lifted aerostats, commonly referred to as hot air balloons, were built and flown by an estimated 12,000 licensed balloon pilots in the last decade. The evolution of controlling fire in hot air balloons during the first century of ballooning is the subject of this article. The purpose of this assessment is to separate the development of thermally lifted aerostats from the general history of aerostatics which includes all gas balloons such as hydrogen and helium lifted balloons as well as thermally lifted balloons. -

Airships Over Lincolnshire

Airships over Lincolnshire AIRSHIPS Over Lincolnshire explore • discover • experience explore Cranwell Aviation Heritage Museum 2 Airships over Lincolnshire INTRODUCTION This file contains material and images which are intended to complement the displays and presentations in Cranwell Aviation Heritage Museum’s exhibition areas. This file looks at the history of military and civilian balloons and airships, in Lincolnshire and elsewhere, and how those balloons developed from a smoke filled bag to the high-tech hybrid airship of today. This file could not have been created without the help and guidance of a number of organisations and subject matter experts. Three individuals undoubtedly deserve special mention: Mr Mike Credland and Mr Mike Hodgson who have both contributed information and images for you, the visitor to enjoy. Last, but certainly not least, is Mr Brian J. Turpin whose enduring support has added flesh to what were the bare bones of the story we are endeavouring to tell. These gentlemen and all those who have assisted with ‘Airships over Lincolnshire’ have the grateful thanks of the staff and volunteers of Cranwell Aviation Heritage Museum. Airships over Lincolnshire 3 CONTENTS Early History of Ballooning 4 Balloons – Early Military Usage 6 Airship Types 7 Cranwell’s Lighter than Air section 8 Cranwell’s Airships 11 Balloons and Airships at Cranwell 16 Airship Pioneer – CM Waterlow 27 Airship Crews 30 Attack from the Air 32 Zeppelin Raids on Lincolnshire 34 The Zeppelin Raid on Cleethorpes 35 Airships during the inter-war years -

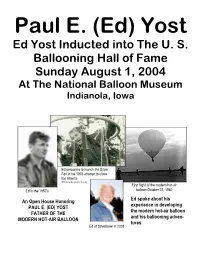

Paul E. (Ed) Yost Ed Yost Inducted Into the U

Paul E. (Ed) Yost Ed Yost Inducted into The U. S. Ballooning Hall of Fame Sunday August 1, 2004 At The National Balloon Museum Indianola, Iowa Ed preparing to launch the Silver Fox in his 1976 attempt to cross the Atlantic © National Geographic Society First flight of the modern hot -air Ed in the 1950’s balloon October 22, 1960 Ed spoke about his An Open House Honoring experience in developing PAUL E. (ED) YOST the modern hot-air balloon FATHER OF THE and his ballooning adven- MODERN HOT-AIR BALLOON tures. Ed at Stratobowl in 2003 ABOUT PAUL E. (ED) YOST Paul Edward Yost was born in Bristow, lowa, about 130 miles from Indianola in 1919. In 1934, when he was 15 years old, Ed and his father set out to .watch the first Explorer flight from the Stratobowl in Rapid City, South Dakota. He has been interested in balloons a long time. Yost was employed by the US Army Air Corps from 1943 to 1945; he flew airplanes in Alaska from 1946 to 1948. Ed Yost is best known as the inventor of the modern hot-air balloon, however in his long and fruitful life he has done many things using and creating balloons. In 1949 Yost started work as Senior Engineer and Tracking Pilot for the High Altitude Research Division of General Mills in Minneapolis, where he worked on many scientific high altitude balloon projects. In 1952 they sent a 3.2 million cubic foot balloon, carrying US Navy instruments, into the stratosphere to study cosmic rays, as part of a scientific project that spanned many years. -

Don Piccard 50 Years & BM

July 1997 $3.50 BALLOON LIFE EDITOR MAGAZINE 50 Years 1997 marks the 50th anniversary for a number of important dates in aviation history Volume 12, Number 7 including the formation of the U.S. Air Force. The most widely known of the 1947 July 1997 Editor-In-Chief “firsts” is Chuck Yeager’s breaking the sound barrier in an experimental jet—the X-1. Publisher Today two other famous firsts are celebrated on television by the “X-Files.” In early Tom Hamilton July near the small southwestern New Mexico town of Roswell the first aliens from outer Contributing Editors space were reported to have been taken into custody when their “flying saucer” crashed Ron Behrmann, George Denniston, and burned. Mike Rose, Peter Stekel The other surreal first had taken place two weeks earlier. Kenneth Arnold observed Columnists a strange sight while flying a search and rescue mission near Mt. Rainier in Washington Christine Kalakuka, Bill Murtorff, Don Piccard state. After he landed in Pendelton, Oregon he told reporters that he had seen a group of Staff Photographer flying objects. He described the ships as being “pie shaped” with “half domes” coming Ron Behrmann out the tops. Arnold coined the term “flying saucers.” Contributors For the last fifty years unidentified flying objects have dominated unexplainable Allen Amsbaugh, Roger Bansemer, sighting in the sky. Even sonic booms from jet aircraft can still generate phone calls to Jan Frjdman, Graham Hannah, local emergency assistance numbers. Glen Moyer, Bill Randol, Polly Anna Randol, Rob Schantz, Today, debate about visitors from another galaxy captures the headlines. -

FLIGHTS of FANCY the Air, the Peaceful Silence, and the Grandeur of the Aspect

The pleasure is in the birdlike leap into FLIGHTS OF FANCY the air, the peaceful silence, and the grandeur of the aspect. The terror lurks above and below. An uncontrolled as- A history of ballooning cent means frostbite, asphyxia, and death in the deep purple of the strato- By Steven Shapin sphere; an uncontrolled return shatters bones and ruptures organs. We’ve always aspired to up-ness: up Discussed in this essay: is virtuous, good, ennobling. Spirits are lifted; hopes are raised; imagination Falling Upwards: How We Took to the Air, by Richard Holmes. Pantheon. 416 pages. soars; ideas get off the ground; the sky’s $35. pantheonbooks.com. the limit (unless you reach for the stars). To excel is to rise above others. Levity ome years ago, when I lived in as photo op, as advertisement, as inti- is, after all, opposed to gravity, and you SCalifornia, a colleague—a distin- mate romantic gesture. But that’s not don’t want your hopes dashed, your guished silver-haired English how it all started: in its late-eighteenth- dreams deated, or your imagination historian—got a surprise birthday pres- century beginnings, ballooning was a brought down to earth. ent from his wife: a sunset hot-air- Romantic gesture on the grandest of In 1783, the French inventor and balloon trip. “It sets the perfect stage for scales, and it takes one of the great his- scientist Jacques Alexandre Charles your romantic escapade,” the balloon torians and biographers of the Romantic wrote of the ballooning experience as company’s advertising copy reads, rec- era to retrieve what it once signied. -

Article the Spectacle of Science Aloft

SISSA – International School for Advanced Studies Journal of Science Communication ISSN 1824 – 2049 http://jcom.sissa.it/ Article The spectacle of science aloft Cristina Olivotto Since the first pioneering balloon flight undertaken in France in 1783, aerial ascents became an ordinary show for the citizens of the great European cities until the end of the XIX century. Scientists welcomed balloons as an extraordinary device to explore the aerial ocean and find answers to their questions. At the same time, due to the theatricality of ballooning, sky became a unique stage where science could make an exhibition of itself. Namely, ballooning was not only a scientific device, but a way to communicate science as well. Starting from studies concerning the public facet of aerial ascents and from the reports of the aeronauts themselves, this essay explores the importance of balloon flights in growing the public sphere of science. Also, the reasons that led scientists to exploit “the show of science aloft” (earning funds, public support, dissemination of scientific culture…) will be presented and discussed. Introduction After the first aerial ascent in 1783, several scientists believed that ballooning could become an irreplaceable device to explore the upper atmosphere: the whole XIX century “gave birth to countless endeavours to render the balloon as navigable in air as the ship at sea”.1 From an analysis of the aerial ascents undertaken for scientific purposes and the characters of the scientists who organized and performed them – no more than 10 aeronauts from the beginning of the century to 1875 – an important feature emerges: ballooning – due to its proper nature - became a powerful tool in attiring a general public toward science, more effectively than scientific papers and oral lectures. -

Paper Takes Flight Teacher Materials

Paper Takes Flight Teacher Materials Contents: LESSON PLAN .............................................................................................................................. 1 Summary: .................................................................................................................................... 1 Objectives:................................................................................................................................... 1 Materials:..................................................................................................................................... 1 Safety Instructions:...................................................................................................................... 1 Background: ................................................................................................................................ 1 Procedure:.................................................................................................................................... 2 Discussion ................................................................................................................................... 2 Assessment/Evaluation:............................................................................................................... 3 Extensions: .................................................................................................................................. 3 Math Integration.........................................................................................................................