Molal Concentration∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modelling and Numerical Simulation of Phase Separation in Polymer Modified Bitumen by Phase- Field Method

http://www.diva-portal.org Postprint This is the accepted version of a paper published in Materials & design. This paper has been peer- reviewed but does not include the final publisher proof-corrections or journal pagination. Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Zhu, J., Lu, X., Balieu, R., Kringos, N. (2016) Modelling and numerical simulation of phase separation in polymer modified bitumen by phase- field method. Materials & design, 107: 322-332 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2016.06.041 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:kth:diva-188830 ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT Modelling and numerical simulation of phase separation in polymer modified bitumen by phase-field method Jiqing Zhu a,*, Xiaohu Lu b, Romain Balieu a, Niki Kringos a a Department of Civil and Architectural Engineering, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Brinellvägen 23, SE-100 44 Stockholm, Sweden b Nynas AB, SE-149 82 Nynäshamn, Sweden * Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] (J. Zhu) Abstract In this paper, a phase-field model with viscoelastic effects is developed for polymer modified bitumen (PMB) with the aim to describe and predict the PMB storage stability and phase separation behaviour. The viscoelastic effects due to dynamic asymmetry between bitumen and polymer are represented in the model by introducing a composition-dependent mobility coefficient. A double-well potential for PMB system is proposed on the basis of the Flory-Huggins free energy of mixing, with some simplifying assumptions made to take into account the complex chemical composition of bitumen. -

Solutes and Solution

Solutes and Solution The first rule of solubility is “likes dissolve likes” Polar or ionic substances are soluble in polar solvents Non-polar substances are soluble in non- polar solvents Solutes and Solution There must be a reason why a substance is soluble in a solvent: either the solution process lowers the overall enthalpy of the system (Hrxn < 0) Or the solution process increases the overall entropy of the system (Srxn > 0) Entropy is a measure of the amount of disorder in a system—entropy must increase for any spontaneous change 1 Solutes and Solution The forces that drive the dissolution of a solute usually involve both enthalpy and entropy terms Hsoln < 0 for most species The creation of a solution takes a more ordered system (solid phase or pure liquid phase) and makes more disordered system (solute molecules are more randomly distributed throughout the solution) Saturation and Equilibrium If we have enough solute available, a solution can become saturated—the point when no more solute may be accepted into the solvent Saturation indicates an equilibrium between the pure solute and solvent and the solution solute + solvent solution KC 2 Saturation and Equilibrium solute + solvent solution KC The magnitude of KC indicates how soluble a solute is in that particular solvent If KC is large, the solute is very soluble If KC is small, the solute is only slightly soluble Saturation and Equilibrium Examples: + - NaCl(s) + H2O(l) Na (aq) + Cl (aq) KC = 37.3 A saturated solution of NaCl has a [Na+] = 6.11 M and [Cl-] = -

Chapter 2: Basic Tools of Analytical Chemistry

Chapter 2 Basic Tools of Analytical Chemistry Chapter Overview 2A Measurements in Analytical Chemistry 2B Concentration 2C Stoichiometric Calculations 2D Basic Equipment 2E Preparing Solutions 2F Spreadsheets and Computational Software 2G The Laboratory Notebook 2H Key Terms 2I Chapter Summary 2J Problems 2K Solutions to Practice Exercises In the chapters that follow we will explore many aspects of analytical chemistry. In the process we will consider important questions such as “How do we treat experimental data?”, “How do we ensure that our results are accurate?”, “How do we obtain a representative sample?”, and “How do we select an appropriate analytical technique?” Before we look more closely at these and other questions, we will first review some basic tools of importance to analytical chemists. 13 14 Analytical Chemistry 2.0 2A Measurements in Analytical Chemistry Analytical chemistry is a quantitative science. Whether determining the concentration of a species, evaluating an equilibrium constant, measuring a reaction rate, or drawing a correlation between a compound’s structure and its reactivity, analytical chemists engage in “measuring important chemical things.”1 In this section we briefly review the use of units and significant figures in analytical chemistry. 2A.1 Units of Measurement Some measurements, such as absorbance, A measurement usually consists of a unit and a number expressing the do not have units. Because the meaning of quantity of that unit. We may express the same physical measurement with a unitless number may be unclear, some authors include an artificial unit. It is not different units, which can create confusion. For example, the mass of a unusual to see the abbreviation AU, which sample weighing 1.5 g also may be written as 0.0033 lb or 0.053 oz. -

Parametrisation in Electrostatic DPD Dynamics and Applications

Parametrisation in electrostatic DPD Dynamics and Applications E. Mayoraly and E. Nahmad-Acharz February 19, 2016 y Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Nucleares, Carretera M´exico-Toluca S/N, La Marquesa Ocoyoacac, Edo. de M´exicoC.P. 52750, M´exico z Instituto de Ciencias Nucleares, Universidad Nacional Aut´onomade M´exico, Apartado Postal 70-543, 04510 M´exico DF, Mexico abstract A brief overview of mesoscopic modelling via dissipative particle dynamics is presented, with emphasis on the appropriate parametrisation and how to cal- culate the relevant parameters for given realistic systems. The dependence on concentration and temperature of the interaction parameters is also considered, as well as some applications. 1 Introduction In a colloidal dispersion, the stability is governed by the balance between Van der Waals attractive forces and electrostatic repulsive forces, together with steric mechanisms. Being able to model their interplay is of utmost importance to predict the conditions for colloidal stability, which in turn is of major interest in basic research and for industrial applications. Complex fluids are composed typically at least of one or more solvents, poly- meric or non-polymeric surfactants, and crystalline substrates onto which these surfactants adsorb. Neutral polymer adsorption has been extensively studied us- ing mean-field approximations and assuming an adsorbed polymer configuration of loops and tails [1,2,3,4]. Different mechanisms of adsorption affecting the arXiv:1602.05935v1 [physics.chem-ph] 18 Feb 2016 global -

Molarity Versus Molality Concentration of Solutions SCIENTIFIC

Molarity versus Molality Concentration of Solutions SCIENTIFIC Introduction Simple visual models using rubber stoppers and water in a cylinder help to distinguish between molar and molal concentrations of a solute. Concepts • Solutions • Concentration Materials Graduated cylinder, 1-L, 2 Water, 2-L Rubber stoppers, large, 12 Safety Precautions Watch for spills. Wear chemical splash goggles and always follow safe laboratory procedures when performing demonstrations. Procedure 1. Tell the students that the rubber stoppers represent “moles” of solute. 2. Make a “6 Molar” solution by placing six of the stoppers in a 1-L graduated cylinder and adding just enough water to bring the total volume to 1 liter. 3. Now make a “6 molal” solution by adding six stoppers to a liter of water in the other cylinder. 4. Remind students that a kilogram of water is about equal to a liter of water because the density is about 1 g/mL at room temperature. 5. Set the two cylinders side by side for comparison. Disposal The water may be flushed down the drain. Discussion Molarity, moles of solute per liter of solution, and molality, moles of solute per kilogram of solvent, are concentration expressions that students often confuse. The differences may be slight with dilute aqueous solutions. Consider, for example, a dilute solution of sodium hydroxide. A 0.1 Molar solution consists of 4 g of sodium hydroxide dissolved in approximately 998 g of water, while a 0.1 molal solution consists of 4 g of sodium hydroxide dissolved in 1000 g of water. The amount of water in both solutions is virtually the same. -

THE SOLUBILITY of GASES in LIQUIDS Introductory Information C

THE SOLUBILITY OF GASES IN LIQUIDS Introductory Information C. L. Young, R. Battino, and H. L. Clever INTRODUCTION The Solubility Data Project aims to make a comprehensive search of the literature for data on the solubility of gases, liquids and solids in liquids. Data of suitable accuracy are compiled into data sheets set out in a uniform format. The data for each system are evaluated and where data of sufficient accuracy are available values are recommended and in some cases a smoothing equation is given to represent the variation of solubility with pressure and/or temperature. A text giving an evaluation and recommended values and the compiled data sheets are published on consecutive pages. The following paper by E. Wilhelm gives a rigorous thermodynamic treatment on the solubility of gases in liquids. DEFINITION OF GAS SOLUBILITY The distinction between vapor-liquid equilibria and the solubility of gases in liquids is arbitrary. It is generally accepted that the equilibrium set up at 300K between a typical gas such as argon and a liquid such as water is gas-liquid solubility whereas the equilibrium set up between hexane and cyclohexane at 350K is an example of vapor-liquid equilibrium. However, the distinction between gas-liquid solubility and vapor-liquid equilibrium is often not so clear. The equilibria set up between methane and propane above the critical temperature of methane and below the criti cal temperature of propane may be classed as vapor-liquid equilibrium or as gas-liquid solubility depending on the particular range of pressure considered and the particular worker concerned. -

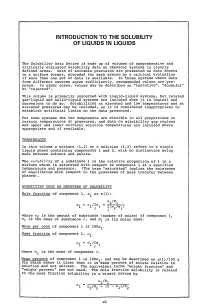

Introduction to the Solubility of Liquids in Liquids

INTRODUCTION TO THE SOLUBILITY OF LIQUIDS IN LIQUIDS The Solubility Data Series is made up of volumes of comprehensive and critically evaluated solubility data on chemical systems in clearly defined areas. Data of suitable precision are presented on data sheets in a uniform format, preceded for each system by a critical evaluation if more than one set of data is available. In those systems where data from different sources agree sufficiently, recommended values are pro posed. In other cases, values may be described as "tentative", "doubtful" or "rejected". This volume is primarily concerned with liquid-liquid systems, but related gas-liquid and solid-liquid systems are included when it is logical and convenient to do so. Solubilities at elevated and low 'temperatures and at elevated pressures may be included, as it is considered inappropriate to establish artificial limits on the data presented. For some systems the two components are miscible in all proportions at certain temperatures or pressures, and data on miscibility gap regions and upper and lower critical solution temperatures are included where appropriate and if available. TERMINOLOGY In this volume a mixture (1,2) or a solution (1,2) refers to a single liquid phase containing components 1 and 2, with no distinction being made between solvent and solute. The solubility of a substance 1 is the relative proportion of 1 in a mixture which is saturated with respect to component 1 at a specified temperature and pressure. (The term "saturated" implies the existence of equilibrium with respect to the processes of mass transfer between phases) • QUANTITIES USED AS MEASURES OF SOLUBILITY Mole fraction of component 1, Xl or x(l): ml/Ml nl/~ni = r(m.IM.) '/. -

Chapter 15: Solutions

452-487_Ch15-866418 5/10/06 10:51 AM Page 452 CHAPTER 15 Solutions Chemistry 6.b, 6.c, 6.d, 6.e, 7.b I&E 1.a, 1.b, 1.c, 1.d, 1.j, 1.m What You’ll Learn ▲ You will describe and cate- gorize solutions. ▲ You will calculate concen- trations of solutions. ▲ You will analyze the colliga- tive properties of solutions. ▲ You will compare and con- trast heterogeneous mixtures. Why It’s Important The air you breathe, the fluids in your body, and some of the foods you ingest are solu- tions. Because solutions are so common, learning about their behavior is fundamental to understanding chemistry. Visit the Chemistry Web site at chemistrymc.com to find links about solutions. Though it isn’t apparent, there are at least three different solu- tions in this photo; the air, the lake in the foreground, and the steel used in the construction of the buildings are all solutions. 452 Chapter 15 452-487_Ch15-866418 5/10/06 10:52 AM Page 453 DISCOVERY LAB Solution Formation Chemistry 6.b, 7.b I&E 1.d he intermolecular forces among dissolving particles and the Tattractive forces between solute and solvent particles result in an overall energy change. Can this change be observed? Safety Precautions Dispose of solutions by flushing them down a drain with excess water. Procedure 1. Measure 10 g of ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) and place it in a Materials 100-mL beaker. balance 2. Add 30 mL of water to the NH4Cl, stirring with your stirring rod. -

Hydrophobic Forces Between Protein Molecules in Aqueous Solutions of Concentrated Electrolyte

LBNL-47348 Pre print !ERNEST ORLANDO LAWRENCE BERKELEY NATIONAL LABORATORY Hydrophobic Forces Between Protein Molecules in Aqueous Solutions of Concentrated Electrolyte R.A. Curtis, C. Steinbrecher, M. Heinemann, H.W. Blanch, and J .M. Prausnitz Chemical Sciences Division January 2001 Submitted to Biophysical]ournal - r \ ' ,,- ' -· ' .. ' ~. ' . .. "... i ' - (_ '·~ -,.__,_ .J :.r? r Clz r I ~ --.1 w ~ CD DISCLAIMER This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by the United States Government. While this document is believed to contain correct information, neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor the Regents of the University of California, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by its trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof, or the Regents of the University of California. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof or the Regents of the University of California. LBNL-47348 Hydrophobic Forces Between Protein Molecules in Aqueous Solutions of Concentrated Electrolyte R. A. Curtis, C. Steinbrecher. M. Heinemann, H. W. Blanch and J. M. Prausnitz Department of Chemical Engineering University of California and Chemical Sciences Division Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory University of California Berkeley, CA 94720, U.S.A. -

Δtb = M × Kb, Δtf = M × Kf

8.1HW Colligative Properties.doc Colligative Properties of Solvents Use the Equations given in your notes to solve the Colligative Property Questions. ΔTb = m × Kb, ΔTf = m × Kf Freezing Boiling K K Solvent Formula Point f b Point (°C) (°C/m) (°C/m) (°C) Water H2O 0.000 100.000 1.858 0.521 Acetic acid HC2H3O2 16.60 118.5 3.59 3.08 Benzene C6H6 5.455 80.2 5.065 2.61 Camphor C10H16O 179.5 ... 40 ... Carbon disulfide CS2 ... 46.3 ... 2.40 Cyclohexane C6H12 6.55 80.74 20.0 2.79 Ethanol C2H5OH ... 78.3 ... 1.07 1. Which solvent’s freezing point is depressed the most by the addition of a solute? This is determined by the Freezing Point Depression constant, Kf. The substance with the highest value for Kf will be affected the most. This would be Camphor with a constant of 40. 2. Which solvent’s freezing point is depressed the least by the addition of a solute? By the same logic as above, the substance with the lowest value for Kf will be affected the least. This is water. Certainly the case could be made that Carbon disulfide and Ethanol are affected the least as they do not have a constant. 3. Which solvent’s boiling point is elevated the least by the addition of a solute? Water 4. Which solvent’s boiling point is elevated the most by the addition of a solute? Acetic Acid 5. How does Kf relate to Kb? Kf > Kb (fill in the blank) The freezing point constant is always greater. -

Lecture 3. the Basic Properties of the Natural Atmosphere 1. Composition

Lecture 3. The basic properties of the natural atmosphere Objectives: 1. Composition of air. 2. Pressure. 3. Temperature. 4. Density. 5. Concentration. Mole. Mixing ratio. 6. Gas laws. 7. Dry air and moist air. Readings: Turco: p.11-27, 38-43, 366-367, 490-492; Brimblecombe: p. 1-5 1. Composition of air. The word atmosphere derives from the Greek atmo (vapor) and spherios (sphere). The Earth’s atmosphere is a mixture of gases that we call air. Air usually contains a number of small particles (atmospheric aerosols), clouds of condensed water, and ice cloud. NOTE : The atmosphere is a thin veil of gases; if our planet were the size of an apple, its atmosphere would be thick as the apple peel. Some 80% of the mass of the atmosphere is within 10 km of the surface of the Earth, which has a diameter of about 12,742 km. The Earth’s atmosphere as a mixture of gases is characterized by pressure, temperature, and density which vary with altitude (will be discussed in Lecture 4). The atmosphere below about 100 km is called Homosphere. This part of the atmosphere consists of uniform mixtures of gases as illustrated in Table 3.1. 1 Table 3.1. The composition of air. Gases Fraction of air Constant gases Nitrogen, N2 78.08% Oxygen, O2 20.95% Argon, Ar 0.93% Neon, Ne 0.0018% Helium, He 0.0005% Krypton, Kr 0.00011% Xenon, Xe 0.000009% Variable gases Water vapor, H2O 4.0% (maximum, in the tropics) 0.00001% (minimum, at the South Pole) Carbon dioxide, CO2 0.0365% (increasing ~0.4% per year) Methane, CH4 ~0.00018% (increases due to agriculture) Hydrogen, H2 ~0.00006% Nitrous oxide, N2O ~0.00003% Carbon monoxide, CO ~0.000009% Ozone, O3 ~0.000001% - 0.0004% Fluorocarbon 12, CF2Cl2 ~0.00000005% Other gases 1% Oxygen 21% Nitrogen 78% 2 • Some gases in Table 3.1 are called constant gases because the ratio of the number of molecules for each gas and the total number of molecules of air do not change substantially from time to time or place to place. -

Chemistry 1220 Chapter 17 Practice Exam

Dr. Fus CHEM 1220 CHEMISTRY 1220 CHAPTER 17 PRACTICE EXAM All questions listed below are problems taken from old Chemistry 123 exams given here at The Ohio State University. Read Chapter 17.4 – 17.7 and complete the following problems. These problems will not be graded or collected, but will be very similar to what you will see on an exam. Ksp and Molar Solubility (Section 17.4) The solubility product expression equals the product of the concentrations of the ions involved in the equilibrium, each raised to the power of its coefficient in the equilibrium expression. For example: PbCl2(s) Pb2+(aq) + 2Cl-(aq) Ksp=[Pb2+] [Cl-]2 Why isn’t the concentration of PbCl2 in the denominator of the Ksp? Recall from Section 15.4 that whenever a pure solid or pure liquid is in a heterogeneous (multiple phases present) equilibrium, its concentration is not included in the equilibrium expression. 1. The solubility product expression for La2(CO3)3 is Ksp = ? First, write the equilibrium expression. The subscript following each atom in the solid is the number of ions of that atom in solution. The total charges must add to zero: La2(CO3)3(s) 2La3+(aq) + 3CO32-(aq) Given the information above and the equilibrium expression: Ksp=[La3+]2 [CO32-]3 2. The solubility product expression for Zn3(PO4)2 is Ksp = ? Zn3(PO4)2(s) 3Zn2+(aq) + 2PO43-(aq) Ksp=[Zn2+]3 [PO43-]2 3. The solubility product expression for Al2(CO3)3 is Ksp = ? Al2(CO3)3(s) 2Al3+(aq) + 3CO32-(aq) Ksp=[Al3+]2 [CO32-]3 4.