Rembrandt's Portrait(S)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rembrandt Van Rijn

Rembrandt van Rijn 1606-1669 REMBRANDT HARMENSZ. VAN RIJN, born 15 July er (1608-1651), Govaert Flinck (1615-1660), and 1606 in Leiden, was the son of a miller, Harmen Ferdinand Bol (1616-1680), worked during these Gerritsz. van Rijn (1568-1630), and his wife years at Van Uylenburgh's studio under Rem Neeltgen van Zuytbrouck (1568-1640). The brandt's guidance. youngest son of at least ten children, Rembrandt In 1633 Rembrandt became engaged to Van was not expected to carry on his father's business. Uylenburgh's niece Saskia (1612-1642), daughter Since the family was prosperous enough, they sent of a wealthy and prominent Frisian family. They him to the Leiden Latin School, where he remained married the following year. In 1639, at the height of for seven years. In 1620 he enrolled briefly at the his success, Rembrandt purchased a large house on University of Leiden, perhaps to study theology. the Sint-Anthonisbreestraat in Amsterdam for a Orlers, Rembrandt's first biographer, related that considerable amount of money. To acquire the because "by nature he was moved toward the art of house, however, he had to borrow heavily, creating a painting and drawing," he left the university to study debt that would eventually figure in his financial the fundamentals of painting with the Leiden artist problems of the mid-1650s. Rembrandt and Saskia Jacob Isaacsz. van Swanenburgh (1571 -1638). After had four children, but only Titus, born in 1641, three years with this master, Rembrandt left in 1624 survived infancy. After a long illness Saskia died in for Amsterdam, where he studied for six months 1642, the very year Rembrandt painted The Night under Pieter Lastman (1583-1633), the most impor Watch (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam). -

Gary Schwartz

Gary Schwartz A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings as a Test Case for Connoisseurship Seldom has an exercise in connoisseurship had more going for it than the world-famous Rembrandt Research Project, the RRP. This group of connoisseurs set out in 1968 to establish a corpus of Rembrandt paintings in which doubt concer- ning attributions to the master was to be reduced to a minimum. In the present enquiry, I examine the main lessons that can be learned about connoisseurship in general from the first three volumes of the project. My remarks are limited to two central issues: the methodology of the RRP and its concept of authorship. Concerning methodology,I arrive at the conclusion that the persistent appli- cation of classical connoisseurship by the RRP, attended by a look at scientific examination techniques, shows that connoisseurship, while opening our eyes to some features of a work of art, closes them to others, at the risk of generating false impressions and incorrect judgments.As for the concept of authorship, I will show that the early RRP entertained an anachronistic and fatally puristic notion of what constitutes authorship in a Dutch painting of the seventeenth century,which skewed nearly all of its attributions. These negative judgments could lead one to blame the RRP for doing an inferior job. But they can also be read in another way. If the members of the RRP were no worse than other connoisseurs, then the failure of their enterprise shows that connoisseurship was unable to deliver the advertised goods. I subscribe to the latter conviction. This paper therefore ends with a proposal for the enrichment of Rembrandt studies after the age of connoisseurship. -

Openeclanewfieldinthehis- Work,Ret

-t horizonte Beitràge zu Kunst und Kunstwissenschaft horizons Essais sur I'art et sur son histoire orizzonti Saggi sull'arte e sulla storia dell'arte horizons Essays on Art and Art Research Hatje Cantz 50 Jahre Schweizerisches lnstitut flir Kunstwissenschaft 50 ans lnstitut suisse pour l'étude de I'art 50 anni lstituto svizzero di studi d'arte 50 Years Swiss lnstitute for Art Research Gary Schwartz The Clones Make the Master: Rembrandt in 1ó50 A high point brought low The year r65o was long considerecl a high point ot w-atershed fcrr Rem- a painr- orandt ls a painter. a date of qrear significance in his carecr' Of ng dated ,65o, n French auction catalogue of 18o6 writes: 'sa date prouve qu'il était dans sa plus grande force'" For John Smith, the com- pl.. of ih. firr, catalogue of the artistt paintings in r836, 165o was the golden age.' This convictíon surl ived well into zenith of Rembranclt's (It :]re tnentieth centufy. Ifl 1942, Tancred Borenius wfote: was about r65o one me-v sa)i that the characteristics of Rembrandt's final manner Rosenberg in r.rr e become cleady pronounced.'l 'This date,'wroteJakob cat. Paris, ro-rr r8o6 (l'ugt 'Rembrandt: life and wotk' (r9+8/ ry64),the standard texl on the master 1 Sale June t)).n\t.1o. Fr,,m thq sxns'6rjp1 rrl years, 'can be called the end of his middle period, or equallv Jt :,r many the entrv on thc painting i n the Corpns of this ''e11, the beginning of his late one.'a Bob Haak, in 1984, enriched Renbrandt paintings, r'ith thanks to the that of Rcmbrandt Research Project for show-ing ,r.rqe b1, contrasting Rembrandt's work aftet mid-centurl' with to me this and other sections of the draft 'Rembrandt not only kept his distance from the new -. -

SKETCHBOOK TRAVELER: HUDSON VALLEY a Field Guide to Mindful Travel Through Drawing & Writing

SKETCHBOOK TRAVELER: HUDSON VALLEY A Field Guide to Mindful Travel through Drawing & Writing MATERIALS & EQUIPMENT Anything that makes a mark, and any surface that takes a mark will be perfectly suitable. If you prefer to go to the field accoutered in style, below is a list of optional supplies. SKETCHBOOKS FIELD ARTIST. Watercolor sketchbooks. Various sizes. MOLESKINE. Watercolor sketchbooks. Various sizes. HAND BOOK. Watercolor sketchbook. Various sizes. Recommended: Moleskine Watercolor Sketchbook BRUSHES DAVINCI Travel brushes. https://www.amazon.com/Vinci-CosmoTop-Watercolor-Synthetic- Protective/dp/B00409FCLE/ref=sr_1_4?crid=159I8HND5YMOY&dchild=1&keywords=da+vinci+t ravel+watercolor+brushes&qid=1604518669&s=arts-crafts&sprefix=da+vinci+travel+%2Carts- crafts%2C159&sr=1-4 ESCODA Travel brushes. https://www.amazon.com/Escoda-1468-Travel-Brush- Set/dp/B00CVB62U8 RICHESON Plein air watercolor brush set. https://products.richesonart.com/products/gm- travel-sets WATERCOLORS: Tube and Half-Pans WATERCOLORS L. CORNELISSEN & SON. (London) Full selection of pans, tubes, and related materials. Retail walk-in and online sales. https://www.cornelissen.com MAIMERI. Watercolors. Italy. http://www.maimeri.it GOLDEN PAINTS. QoR Watercolors (recommended) The gold standard in acrylic colors for artists, Golden has developed a new line of watercolors marketed as QoR. It has terrific pigment density and uses a water-soluble synthetic binder in place of Gum Arabic https://www.qorcolors.com KREMER PIGMENTE. (Germany & NYC) Selection of travel sets and related materials. Online and walk-in retail sales. https://shop.kremerpigments.com/en/ SAVOIR-FAIRE is the official representative of Sennelier products in the USA. Also carries a full selection of brushes, papers and miscellaneous equipment. -

Evolution and Ambition in the Career of Jan Lievens (1607-1674)

ABSTRACT Title: EVOLUTION AND AMBITION IN THE CAREER OF JAN LIEVENS (1607-1674) Lloyd DeWitt, Ph.D., 2006 Directed By: Prof. Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Department of Art History and Archaeology The Dutch artist Jan Lievens (1607-1674) was viewed by his contemporaries as one of the most important artists of his age. Ambitious and self-confident, Lievens assimilated leading trends from Haarlem, Utrecht and Antwerp into a bold and monumental style that he refined during the late 1620s through close artistic interaction with Rembrandt van Rijn in Leiden, climaxing in a competition for a court commission. Lievens’s early Job on the Dung Heap and Raising of Lazarus demonstrate his careful adaptation of style and iconography to both theological and political conditions of his time. This much-discussed phase of Lievens’s life came to an end in 1631when Rembrandt left Leiden. Around 1631-1632 Lievens was transformed by his encounter with Anthony van Dyck, and his ambition to be a court artist led him to follow Van Dyck to London in the spring of 1632. His output of independent works in London was modest and entirely connected to Van Dyck and the English court, thus Lievens almost certainly worked in Van Dyck’s studio. In 1635, Lievens moved to Antwerp and returned to history painting, executing commissions for the Jesuits, and he also broadened his artistic vocabulary by mastering woodcut prints and landscape paintings. After a short and successful stay in Leiden in 1639, Lievens moved to Amsterdam permanently in 1644, and from 1648 until the end of his career was engaged in a string of important and prestigious civic and princely commissions in which he continued to demonstrate his aptitude for adapting to and assimilating the most current style of his day to his own somber monumentality. -

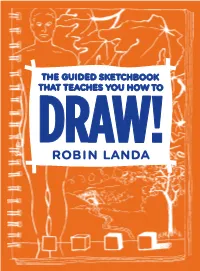

THE GUIDED SKETCHBOOK THAT TEACHES YOU HOW to DRAW! Always Wanted to Learn How to Draw? Now’S Your Chance

Final spine = 0.75 in. Book trims with rounded corners THE GUIDED SKETCHBOOK THAT TEACHES YOU HOW TO HOW YOU TEACHES THAT THE GUIDED SKETCHBOOK THE GUIDED SKETCHBOOK THAT TEACHES YOU HOW TO DRAW! Always wanted to learn how to draw? Now’s your chance. Kean University Teacher of the Year Robin Landa has cleverly disguised an entire college-level course on drawing in this fun, hands-on, begging-to-be-drawn-in sketchbook. Even if you’re one of the four people on this planet who have never picked up a pencil before, you will learn how to transform your doodles into realistic drawings that actually resemble what you’re picturing in your head. In this book, you will learn how to use all of the formal elements of drawing—line, shape, value, color, pattern, and texture—to create well-composed still lifes, landscapes, human figures, and faces. Keep your pencils handy while you’re reading because you’re going to get plenty of drawing breaks— and you can do most of them right in the book while the techniques are fresh in your mind. To keep you inspired, Landa breaks up the step-by-step instruction with drawing suggestions and examples from a host of creative contributors including designers Stefan G. Bucher and Jennifer Sterling, artist Greg Leshé, illustrator Mary Ann Smith, animator Hsinping Pan, and more. Robin Landa, Distinguished Professor in the Robert Busch School of Design at Kean University, draws, designs, and has written 21 books about art, design, creativity, advertising, and branding. Robin’s books include the bestseller Graphic Design Solutions (now in its 5th edition); Build Your Own Brand: Strategies, Prompts and Exercises for Marketing Yourself; and Take A Line For A Walk: A Creativity Journal. -

Ontdek Schilder, Tekenaar, Prentkunstenaar Willem Drost

24317 5 afbeeldingen Willem Drost man / Noord-Nederlands schilder, tekenaar, prentkunstenaar, etser Naamvarianten In dit veld worden niet-voorkeursnamen zoals die in bronnen zijn aangetroffen, vastgelegd en toegankelijk gemaakt. Dit zijn bijvoorbeeld andere schrijfwijzen, bijnamen of namen van getrouwde vrouwen met of juist zonder de achternaam van een echtgenoot. Drost, Cornelis Drost, Geraerd Droste, Willem van Drost, Willem Jansz. Drost, Guglielmo Drost, Wilhelm signed in Italy: 'G. Drost' (G. for Guglielmo). Because of this signature, he was formerly wrongly also called Cornelis or Geraerd Drost. In the past his biography was partly mixed up with that of the Dordrecht painter Jacob van Dorsten. Kwalificaties schilder, tekenaar, prentkunstenaar, etser Nationaliteit/school Noord-Nederlands Geboren Amsterdam 1633-04/1633-04-19 baptized on 19 April 1633 in the Nieuwe Kerk in Amsterdam (Dudok van Heel 1992) Overleden Venetië 1659-02/1659-02-25 buried on 25 February 1659 in the parish of S. Silvestro (Bikker 2001 and Bikker 2002). He had been ill for four months when he dued of fever and pneumonia. Familierelaties in dit veld wordt een familierelatie met één of meer andere kunstenaars vermeld. son of Jan Barentsen (1587-1639) and Maritje Claesdr. (1591-1656). His brother Claes Jansz. Drost (1621-1689) was an ebony worker. Zie ook in dit veld vindt u verwijzingen naar een groepsnaam of naar de kunstenaars die deel uitma(a)k(t)en van de groep. Ook kunt u verwijzingen naar andere kunstenaars aantreffen als het gaat om samenwerking zonder dat er sprake is van een groep(snaam). Dit is bijvoorbeeld het geval bij kunstenaars die gedeelten in werken van een andere kunstenaar voor hun rekening hebben genomen (zoals bij P.P. -

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton Hawley III Jamaica Plain, MA M.A., History of Art, Institute of Fine Arts – New York University, 2010 B.A., Art History and History, College of William and Mary, 2008 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art and Architectural History University of Virginia May, 2015 _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................. i Acknowledgements.......................................................................................................................... ii Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Life of Cornelis Visscher .......................................................................................... 3 Early Life and Family .................................................................................................................... 4 Artistic Training and Guild Membership ...................................................................................... 9 Move to Amsterdam ................................................................................................................. -

Early Utah Women Artists Utah Museum of Fine Arts • Lesson Plans for Educators October 28, 1998 Table of Contents

Early Utah Women Artists Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Lesson Plans for Educators October 28, 1998 Table of Contents Page Contents 2 Image List 3 Edge of the Desert , Louise Richards Farnsworth 4 Lesson Plan for Edge of the Desert Written by Ann Parker 8 Untitled, Mabel Pearl Fraser 9 Lesson Plan for Untitled Written by Betsy Quintana 10 Étude, Harriet Richards Harwood 11 Lesson Plan for Etude Written by Betsy Quintana 13 Battle of the Bulls , Minerva Kohlhepp Teichert 14 Lesson Plan for Battle of the Bulls Written by Marsha Kinghorn 17 Landscape with Blue Mountain and Stream, Florence Ellen Ware 18 Lesson Plan for Landscape with Blue Mountain Written by Bernadette Brown 19 Portrait of the Artist or Her Sister Augusta , Myra L. Sawyer 20 Lesson Plan for Portrait of the Artist or Her Augusta Written by Ila Devereaux Evening for Educators is funded in part by the StateWide Art Partnership 1 Early Utah Women Artists Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Lesson Plans for Educators October 28, 1998 Image List 1. Louise Richard Farnsworth (1878-1969) American Edge of the Desert Oil painting Mr. & Mrs. Joseph J. Palmer 1991.069.023 2. Mabel Pearl Frazer (1887-1981) American Untitled Oil painting Mr. & Mrs. Joseph J. Palmer 1991.069.028 3. Harriet Richards Harwood (1870-1922) American Étude , 1892 Oil painting University of Utah Collection X.035 4. Minerva Kohlhepp Teichert (1888-1976) American Battle of the Bulls Oil painting Gift of Jack and Mary Lois Wheatley 2004.2.1 5. -

The Circumcision 1661 Oil on Canvas Overall: 56.5 X 75 Cm (22 1/4 X 29 1/2 In.) Framed: 81.3 X 99 X 8.2 Cm (32 X 39 X 3 1/4 In.) Inscription: Lower Right: Rembrandt

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Rembrandt van Rijn Dutch, 1606 - 1669 The Circumcision 1661 oil on canvas overall: 56.5 x 75 cm (22 1/4 x 29 1/2 in.) framed: 81.3 x 99 x 8.2 cm (32 x 39 x 3 1/4 in.) Inscription: lower right: Rembrandt. f. 1661 Widener Collection 1942.9.60 ENTRY The only mention of the circumcision of Christ occurs in the Gospel of Luke, 2:15–22: “the shepherds said one to another, Let us now go even unto Bethlehem.... And they came with haste, and found Mary and Joseph, and the babe lying in a manger.... And when eight days were accomplished for the circumcising of the child, his name was called Jesus.” This cursory reference to this most significant event in the early childhood of Christ allowed artists throughout history a wide latitude in the way they represented the circumcision. [1] The predominant Dutch pictorial tradition was to depict the scene as though it occurred within the temple, as, for example, in Hendrick Goltzius (Dutch, 1558 - 1617)’ influential engraving of the Circumcision of Christ, 1594 [fig. 1]. [2] In the Goltzius print, the mohel circumcises the Christ child, held by the high priest, as Mary and Joseph stand reverently to the side. Rembrandt largely followed this tradition in his two early etchings of the subject and in his 1646 painting of the Circumcision for Prince Frederik Hendrik (now lost). [3] The Circumcision 1 © National Gallery of Art, Washington National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century The iconographic tradition of the circumcision occurring in the temple, which was almost certainly apocryphal, developed in the twelfth century to allow for a typological comparison between the Jewish rite of circumcision and the Christian rite of cleansing, or baptism. -

11 Corporate Governance

144 11 Corporate governance MARJOLEIN ’T HART The Bank of Amsterdam´s commissioners: a strong network For almost 200 years, up to the 1780s, the Bank of Amsterdam operated to the great satisfaction of the mercantile elite. Its ability to earn and retain the confidence of the financial and commercial elite was highly dependent on its directors, the commissioners. An analysis of their backgrounds shows that many of them once held senior posts in the city council, although the number of political heavyweights decreased over time. The commissioners also took office at an increasingly younger age. After the first 50 years of the bank, they began to stay on in office longer, indicating a certain degree of professionalisation. The commissioners had excellent connections with stock exchange circles. The majority of them were merchants or bankers themselves, and they almost all had accounts with the bank. As a result, the commissioners formed a very strong network linking the city with the mercantile community. CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 145 François Beeldsnijder, 1688-1765, iron merchant and commissioner of the Bank of Amsterdam for 15 years Jan Baptista Slicher; Amsterdam, 1689-1766, burgomaster, merchant, VOC director and commissioner of the Bank of Amsterdam for 16 years A REVOLUTIONARY PROPOSAL This was the first time that the commissioners of the On 6 June 1797, in the wake of revolutionary upheaval, Bank of Amsterdam had come in for such sharp criticism. Amsterdam’s city council, which had itself undergone Of course, some aspects of the bank had been commented radical change, decided on a revolutionary put forward on before. -

Rembrandt Remembers – 80 Years of Small Town Life

Rembrandt School Song Purple and white, we’re fighting for you, We’ll fight for all things that you can do, Basketball, baseball, any old game, We’ll stand beside you just the same, And when our colors go by We’ll shout for you, Rembrandt High And we'll stand and cheer and shout We’re loyal to Rembrandt High, Rah! Rah! Rah! School colors: Purple and White Nickname: Raiders and Raiderettes Rembrandt Remembers: 80 Years of Small-Town Life Compiled and Edited by Helene Ducas Viall and Betty Foval Hoskins Des Moines, Iowa and Harrisonburg, Virginia Copyright © 2002 by Helene Ducas Viall and Betty Foval Hoskins All rights reserved. iii Table of Contents I. Introduction . v Notes on Editing . vi Acknowledgements . vi II. Graduates 1920s: Clifford Green (p. 1), Hilda Hegna Odor (p. 2), Catherine Grigsby Kestel (p. 4), Genevieve Rystad Boese (p. 5), Waldo Pingel (p. 6) 1930s: Orva Kaasa Goodman (p. 8), Alvin Mosbo (p. 9), Marjorie Whitaker Pritchard (p. 11), Nancy Bork Lind (p. 12), Rosella Kidman Avansino (p. 13), Clayton Olson (p. 14), Agnes Rystad Enderson (p. 16), Alice Haroldson Halverson (p. 16), Evelyn Junkermeier Benna (p. 18), Edith Grodahl Bates (p. 24), Agnes Lerud Peteler (p. 26), Arlene Burwell Cannoy (p. 28 ), Catherine Pingel Sokol (p. 29), Loren Green (p. 30), Phyllis Johnson Gring (p. 34), Ken Hadenfeldt (p. 35), Lloyd Pressel (p. 38), Harry Edwall (p. 40), Lois Ann Johnson Mathison (p. 42), Marv Erichsen (p. 43), Ruth Hill Shankel (p. 45), Wes Wallace (p. 46) 1940s: Clement Kevane (p. 48), Delores Lady Risvold (p.