Anatomy and Physiology of Ageing 9: the Immune System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

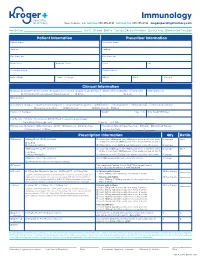

Immunology New Orleans, LA Toll Free 888.355.4191 Toll Free Fax 888.355.4192 Krogerspecialtypharmacy.Com

Immunology New Orleans, LA toll free 888.355.4191 toll free fax 888.355.4192 krogerspecialtypharmacy.com Need By Date: _________________________________________________ Ship To: Patient Office Fax Copy: Rx Card Front/Back Clinical Notes Medical Card Front/Back Patient Information Prescriber Information Patient Name Prescriber Name Address Address City State Zip City State Zip Main Phone Alternate Phone Phone Fax Social Security # Contact Person Date of Birth Male Female DEA # NPI # License # Clinical Information Diagnosis: J45.40 Moderate Asthma J45.50 Severe Asthma L20.9 Atopic Dermatitis L50.1 Chronic Idiopathic Urticaria (CIU) Eosinophil Levels J33 Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyposis Other: ________________________________ Dx Code: ___________ Drug Allergies Concomitant Therapies: Short-acting Beta Agonist Long-acting Beta Agonist Antihistamines Decongestants Immunotherapy Inhaled Corticosteroid Leukotriene Modifiers Oral Steroids Nasal Steroids Other: _____________________________________________________________ Please List Therapies Weight kg lbs Date Weight Obtained Lab Results: History of positive skin OR RAST test to a perennial aeroallergen Pretreatment Serum lgE Level: ______________________________________ IU per mL Test Date: _________ / ________ / ________ MD Specialty: Allergist Dermatologist ENT Pediatrician Primary Care Prescription Type: Naïve/New Start Restart Continued Therapy Pulmonologist Other: _________________________________________ Last Injection Date: _________ / ________ -

IFM Innate Immunity Infographic

UNDERSTANDING INNATE IMMUNITY INTRODUCTION The immune system is comprised of two arms that work together to protect the body – the innate and adaptive immune systems. INNATE ADAPTIVE γδ T Cell Dendritic B Cell Cell Macrophage Antibodies Natural Killer Lymphocites Neutrophil T Cell CD4+ CD8+ T Cell T Cell TIME 6 hours 12 hours 1 week INNATE IMMUNITY ADAPTIVE IMMUNITY Innate immunity is the body’s first The adaptive, or acquired, immune line of immunological response system is activated when the innate and reacts quickly to anything that immune system is not able to fully should not be present. address a threat, but responses are slow, taking up to a week to fully respond. Pathogen evades the innate Dendritic immune system T Cell Cell Through antigen Pathogen presentation, the dendritic cell informs T cells of the pathogen, which informs Macrophage B cells B Cell B cells create antibodies against the pathogen Macrophages engulf and destroy Antibodies label invading pathogens pathogens for destruction Scientists estimate innate immunity comprises approximately: The adaptive immune system develops of the immune memory of pathogen exposures, so that 80% system B and T cells can respond quickly to eliminate repeat invaders. IMMUNE SYSTEM AND DISEASE If the immune system consistently under-responds or over-responds, serious diseases can result. CANCER INFLAMMATION Innate system is TOO ACTIVE Innate system NOT ACTIVE ENOUGH Cancers grow and spread when tumor Certain diseases trigger the innate cells evade detection by the immune immune system to unnecessarily system. The innate immune system is respond and cause excessive inflammation. responsible for detecting cancer cells and This type of chronic inflammation is signaling to the adaptive immune system associated with autoimmune and for the destruction of the cancer cells. -

We Work at the Intersection of Immunology and Developmental Biology

Development and Homeostasis of Mucosal Tissues U934/UMR3215 – Genetics and Developmental Biology Pedro Hernández Chef d'équipe [email protected] We work at the intersection of immunology and developmental biology. Our primary goal is to understand how immune responses impact the development, integrity and function of mucosal tissue layers, such as the intestinal epithelium, during homeostasis and upon different types of stress, including infections. To study these questions we exploit the advantages of the zebrafish model such as ex utero and rapid development, transparency, large progeny, and simple genetic manipulation. We combine live imaging, flow cytometry, single-cell transcriptomics, and models inducing mucosal stress, including pathogenic challenges. Our research can be subdivided into three main topics: 1) Protection of intestinal epithelial integrity since early development: Epithelial cells are at the core of intestinal organ function. They are in charge of absorbing nutrients and water, and at the same time constitute a barrier for potential pathogens and harmful molecules. Epithelial cells perform all these functions before full development of the immune system, which promotes epithelial barrier function upon injury. We study how robust epithelial integrity is achieved prior and after maturation of the intestinal immune system, with a focus on the function of mucosal cytokines. 2) Epithelial-leukocyte crosstalk throughout development: Intestines become vastly populated by leukocytes after exposure to external cues from diet and colonization by the microbiota. We have recently reported the existence and diversity of zebrafish innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), a key component of the mucosal immune system recently discovered in mice and humans. ILCs mediate immune responses by secreting cytokines such as IL-22 which safeguards gut epithelial integrity. -

Our Immune System (Children's Book)

OurOur ImmuneImmune SystemSystem A story for children with primary immunodeficiency diseases Written by IMMUNE DEFICIENCY Sara LeBien FOUNDATION A note from the author The purpose of this book is to help young children who are immune deficient to better understand their immune system. What is a “B-cell,” a “T-cell,” an “immunoglobulin” or “IgG”? They hear doctors use these words, but what do they mean? With cheerful illustrations, Our Immune System explains how a normal immune system works and what treatments may be necessary when the system is deficient. In this second edition, a description of a new treatment has been included. I hope this book will enable these children and their families to explore together the immune system, and that it will help alleviate any confusion or fears they may have. Sara LeBien This book contains general medical information which cannot be applied safely to any individual case. Medical knowledge and practice can change rapidly. Therefore, this book should not be used as a substitute for professional medical advice. SECOND EDITION COPYRIGHT 1990, 2007 IMMUNE DEFICIENCY FOUNDATION Copyright 2007 by Immune Deficiency Foundation, USA. Readers may redistribute this article to other individuals for non-commercial use, provided that the text, html codes, and this notice remain intact and unaltered in any way. Our Immune System may not be resold, reprinted or redistributed for compensation of any kind without prior written permission from Immune Deficiency Foundation. If you have any questions about permission, please contact: Immune Deficiency Foundation, 40 West Chesapeake Avenue, Suite 308, Towson, MD 21204, USA; or by telephone at 1-800-296-4433. -

Immunology Stories: How Storytelling Can Help Us to Make Sense of Complex Topics

Immunology Stories: How Storytelling Can Help Us to Make Sense of Complex Topics Jennifer Giuliani, MSc Camosun College, Lansdowne Campus, 3100 Foul Bay Rd, Victoria BC V8P 5J2 [email protected] Abstract The immune response is a wonderfully complex aspect of our physiology that can sometimes confound students and instructors alike. How do we wade through the layers of detail to help our students develop an understanding of immunology? In this article, I will share some of the stories about immunology research that helped me strengthen my own understanding and improve my approach to helping students learn and understand this topic. In addition, we will explore some of the research on the power of storytelling, and how learning through stories might be a defining characteristic of what it means to be human. https://doi.org/10.21692/haps.2020.105 Key words: storytelling, immunology Introduction I have been trying to understand the immune response for a My personal journey to develop a better understanding of long time. Like many Anatomy and Physiology instructors, I the immune system was a compelling reminder to me of the did not have an immunology background beyond what was power of storytelling. Suddenly I saw examples of storytelling covered in my undergraduate physiology courses. When the everywhere that I saw authentic learning. In this article, I will time came for me to teach students about the immune system, share some of what I have learned about learning through I relied heavily on the information presented in our textbooks. stories, some of the fun and fascinating immunology stories I was able to present students with the key pieces of from Davis’ books, and my current approach to helping information and help them to remember a few facts, and the students understand the immune response. -

Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection

JOURNAL OF MICROBIOLOGY, IMMUNOLOGY AND INFECTION AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK TABLE OF CONTENTS XXX . • Description p.1 • Impact Factor p.1 • Abstracting and Indexing p.2 • Editorial Board p.2 • Guide for Authors p.4 ISSN: 1684-1182 DESCRIPTION . Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection, launched in 1968, is the official bi-monthly publication of the Taiwan Society of Microbiology, the Chinese Society of Immunology, the Infectious Diseases Society of Taiwan and the Taiwan Society of Parasitology. The journal is an open access journal, committed to disseminating information on the latest trends and advances in microbiology, immunology, infectious diseases and parasitology. Articles on clinical or laboratory investigations of relevance to microbiology, immunology, infectious diseases, parasitology and other related fields that are of interest to the medical profession are eligible for consideration. Article types considered include perspectives, review articles, original articles, brief reports and correspondence. The Editorial Board of the Journal comprises a dedicated team of local and international experts in the field of microbiology, immunology, infectious diseases and parasitology. All members of the Editorial Board actively guide and set the direction of the journal. With the aim of promoting effective and accurate scientific information, an expert panel of referees constitutes the backbone of the peer- review process in evaluating the quality and content of manuscripts submitted for publication. JMII is open access and indexed in SCIE, PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, AIDS & Cancer Reseach, CABI, BIOSIS Previews, Biological Abstracts, EBSCOhost, CancerLit, Reactions Weekly (online), Chemical Abstracts, HealthSTAR, Global Health, ProQuest. Benefits to authors We also provide many author benefits, such as free PDFs, a liberal copyright policy, special discounts on Elsevier publications and much more. -

Study Guide Medical Terminology by Thea Liza Batan About the Author

Study Guide Medical Terminology By Thea Liza Batan About the Author Thea Liza Batan earned a Master of Science in Nursing Administration in 2007 from Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. She has worked as a staff nurse, nurse instructor, and level department head. She currently works as a simulation coordinator and a free- lance writer specializing in nursing and healthcare. All terms mentioned in this text that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Use of a term in this text shouldn’t be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Copyright © 2017 by Penn Foster, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to Copyright Permissions, Penn Foster, 925 Oak Street, Scranton, Pennsylvania 18515. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INSTRUCTIONS 1 READING ASSIGNMENTS 3 LESSON 1: THE FUNDAMENTALS OF MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY 5 LESSON 2: DIAGNOSIS, INTERVENTION, AND HUMAN BODY TERMS 28 LESSON 3: MUSCULOSKELETAL, CIRCULATORY, AND RESPIRATORY SYSTEM TERMS 44 LESSON 4: DIGESTIVE, URINARY, AND REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM TERMS 69 LESSON 5: INTEGUMENTARY, NERVOUS, AND ENDOCRINE S YSTEM TERMS 96 SELF-CHECK ANSWERS 134 © PENN FOSTER, INC. 2017 MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY PAGE III Contents INSTRUCTIONS INTRODUCTION Welcome to your course on medical terminology. You’re taking this course because you’re most likely interested in pursuing a health and science career, which entails proficiencyincommunicatingwithhealthcareprofessionalssuchasphysicians,nurses, or dentists. -

Lung Microbiome Participation in Local Immune Response Regulation in Respiratory Diseases

microorganisms Review Lung Microbiome Participation in Local Immune Response Regulation in Respiratory Diseases Juan Alberto Lira-Lucio 1 , Ramcés Falfán-Valencia 1 , Alejandra Ramírez-Venegas 2, Ivette Buendía-Roldán 3 , Jorge Rojas-Serrano 4 , Mayra Mejía 4 and Gloria Pérez-Rubio 1,* 1 HLA Laboratory, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Respiratorias Ismael Cosío Villegas, Mexico City 14080, Mexico; [email protected] (J.A.L.-L.); [email protected] (R.F.-V.) 2 Tobacco Smoking and COPD Research Department, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Respiratorias Ismael Cosío Villegas, Mexico City 14080, Mexico; [email protected] 3 Translational Research Laboratory on Aging and Pulmonary Fibrosis, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Respiratorias Ismael Cosío Villegas, Mexico City 14080, Mexico; [email protected] 4 Interstitial Lung Disease and Rheumatology Unit, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Respiratorias Ismael Cosío Villegas, Mexico City 14080, Mexico; [email protected] (J.R.-S.); [email protected] (M.M.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +52-55-5487-1700 (ext. 5152) Received: 11 June 2020; Accepted: 7 July 2020; Published: 16 July 2020 Abstract: The lung microbiome composition has critical implications in the regulation of innate and adaptive immune responses. Next-generation sequencing techniques have revolutionized the understanding of pulmonary physiology and pathology. Currently, it is clear that the lung is not a sterile place; therefore, the investigation of the participation of the pulmonary microbiome in the presentation, severity, and prognosis of multiple pathologies, such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and interstitial lung diseases, contributes to a better understanding of the pathophysiology. Dysregulation of microbiota components in the microbiome–host interaction is associated with multiple lung pathologies, severity, and prognosis, making microbiome study a useful tool for the identification of potential therapeutic strategies. -

Curriculum Vitae

Wayne T. McCormack, Ph.D. CURRICULUM VITAE PERSONAL DATA Name: Wayne Thomas McCormack Address: Dept. of Pathology, Immunology & Laboratory Medicine University of Florida College of Medicine 1249 Center Drive Communicore Building, Room CG-72K Gainesville, Florida 32610-0208 Telephone: office (352) 294-8334 fax (352) 392-3053 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: http://mccormacklab.pathology.ufl.edu/ EDUCATION High School: Bellevue High School, Bellevue, Nebraska, 1976 Undergraduate: Creighton University, Omaha, Nebraska B.S. (Biology), December 15, 1979 Graduate: Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida M.S., Biological Science (Genetics & Cell Biology), December 18, 1982 Ph.D., Biological Science (Genetics & Cell Biology), December 12, 1987 POSTDOCTORAL TRAINING Research Associate, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, Michigan. November 1987 – February 1989 Postdoctoral Fellow, Dept. of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, Michigan. March 1989 – August 1991 Master Educators of Medical Education, University of Florida College of Medicine. January 2001 – June 2002 AAMC Medical Education Research Certificate (MERC) Program. November 2008 – November 2010 ACADEMIC POSITIONS Distinguished Teaching Scholar & Professor, Dept. of Pathology, Immunology and Laboratory Medicine, Univ. Florida College of Medicine, July 2015 – present Associate Professor, Dept. of Pathology, Immunology and Laboratory Medicine, Univ. Florida College of Medicine, July 1997 – June 2015 Director, Clinical & Translational Science Predoctoral Training Programs, UF Clinical & Translational Science Institute, April 2009 – present Associate Dean for Graduate Education, Univ. Florida College of Medicine, September 2001 – February 2011 Assistant Professor, Dept. of Pathology, Immunology and Laboratory Medicine, Univ. Florida College of Medicine, June 1991 – June 1997 1 Wayne T. McCormack, Ph.D. -

Cells, Tissues and Organs of the Immune System

Immune Cells and Organs Bonnie Hylander, Ph.D. Aug 29, 2014 Dept of Immunology [email protected] Immune system Purpose/function? • First line of defense= epithelial integrity= skin, mucosal surfaces • Defense against pathogens – Inside cells= kill the infected cell (Viruses) – Systemic= kill- Bacteria, Fungi, Parasites • Two phases of response – Handle the acute infection, keep it from spreading – Prevent future infections We didn’t know…. • What triggers innate immunity- • What mediates communication between innate and adaptive immunity- Bruce A. Beutler Jules A. Hoffmann Ralph M. Steinman Jules A. Hoffmann Bruce A. Beutler Ralph M. Steinman 1996 (fruit flies) 1998 (mice) 1973 Discovered receptor proteins that can Discovered dendritic recognize bacteria and other microorganisms cells “the conductors of as they enter the body, and activate the first the immune system”. line of defense in the immune system, known DC’s activate T-cells as innate immunity. The Immune System “Although the lymphoid system consists of various separate tissues and organs, it functions as a single entity. This is mainly because its principal cellular constituents, lymphocytes, are intrinsically mobile and continuously recirculate in large number between the blood and the lymph by way of the secondary lymphoid tissues… where antigens and antigen-presenting cells are selectively localized.” -Masayuki, Nat Rev Immuno. May 2004 Not all who wander are lost….. Tolkien Lord of the Rings …..some are searching Overview of the Immune System Immune System • Cells – Innate response- several cell types – Adaptive (specific) response- lymphocytes • Organs – Primary where lymphocytes develop/mature – Secondary where mature lymphocytes and antigen presenting cells interact to initiate a specific immune response • Circulatory system- blood • Lymphatic system- lymph Cells= Leukocytes= white blood cells Plasma- with anticoagulant Granulocytes Serum- after coagulation 1. -

Wild Immunology: Converging on the Real World

Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. ISSN 0077-8923 ANNALS OF THE NEW YORK ACADEMY OF SCIENCES Issue: Annals Meeting Reports Wild immunology: converging on the real world Simon A. Babayan,1 Judith E. Allen,1 Jan E. Bradley,2 Markus B. Geuking,3 Andrea L. Graham,4 Richard K. Grencis,5 Jim Kaufman,6 Kathy D. McCoy,3 Steve Paterson,7 Kenneth G. C. Smith,8 Peter J. Turnbaugh,9 Mark E. Viney,10 Rick M. Maizels,1 and Amy B. Pedersen1 1Centre for Immunity, Infection and Evolution, Institutes of Immunology and Infection Research, and Evolutionary Biology, School of Biological Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Ashworth Laboratories, Kings Buildings, Edinburgh, United Kingdom. 2School of Biology, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom. 3Department of Clinical Research, Universitatsklinik¨ fur¨ Viszerale Chirurgie und Medizin Inselspital, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland. 4Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey. 5Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom. 6Department of Pathology (and Department of Veterinary Medicine), University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom. 7Institute of Integrative Biology, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, United Kingdom. 8Cambridge Institute for Medical Research and the Department of Medicine, University of Cambridge School of Clinical Medicine, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, United Kingdom. 9FAS Center for Systems Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts. 10School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, United Kingdom Address for correspondence: Amy B. Pedersen, Advanced Fellow, Centre for Immunity, Infection and Evolution, Institutes of Evolutionary Biology, Immunology, and Infection Research, School of Biological Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Kings Buildings, Ashworth Labs, West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3JT, UK. -

COMPREHENSIVE EXAMINATION Immunology, Pathology & Infectious

COMPREHENSIVE EXAMINATION Immunology, Pathology & Infectious Disease Graduate program 1.21.2021 1. Ph.D. students must pass their comprehensive examination no later than three years after the start of their program. M.D./Ph.D. students must pass no later than two year after the start of their Ph.D. program. Students need to have completed all their required and elective courses prior to scheduling their comprehensive examination. 2. The comprehensive examination will consist of review and oral defense of a research grant application written by the student using the National Institute of Health (NIH) investigator-initiated research grant proposal (R21) format. The subject matter of the research grant application must be approved by the student’s Examination Committee and may be in the same general, but not specific, focus area as the student’s proposed dissertation research. The Examination Committee must approve the specific aims of the grant application before the full proposal is written and provide critiques of the full application before the comprehensive examination is scheduled. There is a high expectation that the research proposal will explore new areas of interest. It is also expected that the hypothesis for the proposed research will be the result of a comprehensive review of the literature. Supporting data should be drawn from literature that is current and relevant to the topic. Hypothetical preliminary data is not appropriate. 3. The Examination Committee will consist of the student’s Ph.D. Supervisory Committee and one faculty member outside the student’s Supervisory Committee (often but not necessarily selected for expertise in the area of the research proposal) as well as a member of the Graduate Committee, to both review and participate in the examination.